India

Republnal Informatics Centre |

|---|

[1]}}

| national_motto = "Satyameva Jayate" (Sanskrit)

| national_anthem = "Jana Gana Mana" (Hindi)[lower-alpha 1][1][2]

"Thou Art the Ruler of the Minds of All People"[3][1]

| image_map = India (orthographic projection).svg | map_width = 250px | alt_map = Image of a globe centred on India, with India highlighted. | map_caption = Territory controlled by India shown in dark green; territory claimed but not controlled shown in light green | capital = New Delhi | coordinates = 28°36′50″N 77°12′30″E / 28.61389°N 77.20833°E

| largest_city =

| official_languages =

| regional_languages =

- 8th Scheduled

- Assamese

- Bengali

- Boron the eighth schedule and not all the scheduled languages are state-level official languages. For example, the Sindhi language is an 8th scheduled but not a state-level official language.

| languages_type = Native languages | languages = 447 languages[lower-alpha 4]

| demonym =

| government_type = Federal parliamentary republic

| leader_title1 = President

| leader_name1 = Droupadi Murmu

| leader_title2 = Vice-President

| leader_name2 = Jagdeep Dhankhar

| leader_title3 = Prime Minister

| leader_name3 = Narendra Modi

| legislature = Parliament

| upper_house = Rajya Sabha

| lower_house = Lok Sabha

| sovereignty_type = Independence

| sovereignty_note = from the United Kingdom

| established_event1 = Dominion

| established_date1 = 15 August 1947

| established_event2 = Republic

| established_date2 = 26 January 1950

| established_event3 = Last polity admitted

| established_date3 = 16 May 1975

| area_km2 = 3,287,263[1]

| area_footnote = [lower-alpha 5]

| area_rank = 7th

| area_sq_mi = 1,269,346

| percent_water = 9.6m=1&scc=0&ssd=1&ssc=0&sic=0&sort=country&ds=.&br=1 |title=World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (India) |publisher=International Monetary Fund |website=IMF.org |date=10 October 2023 |access-date=12 October 2023}}</ref>

| GDP_PPP_year = 2023

| GDP_PPP_rank = 3rd

| GDP_PPP_per_capita = ![]() $9,183[12]

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 127th

| GDP_nominal =

$9,183[12]

| GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = 127th

| GDP_nominal = ![]() $3.732 trillion[12]

| GDP_nominal_year = 2023

| GDP_nominal_rank = 5th

| GDP_nominal_per_capita =

$3.732 trillion[12]

| GDP_nominal_year = 2023

| GDP_nominal_rank = 5th

| GDP_nominal_per_capita = ![]() $2,612[12]

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 139th

| Gini = 35.7

| Gini_year = 2019

| Gini_change = increase

| Gini_ref =[13]

| HDI = 0.633

| HDI_year = 2021

| HDI_change = increase

| HDI_ref =[14]

| HDI_rank = 132nd

| currency = Indian rupee (₹)

| currency_code = INR

| time_zone = IST

| utc_offset = +05:30

| utc_offset_DST =

| DST_note = DST is not observed.

| time_zone_DST =

$2,612[12]

| GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = 139th

| Gini = 35.7

| Gini_year = 2019

| Gini_change = increase

| Gini_ref =[13]

| HDI = 0.633

| HDI_year = 2021

| HDI_change = increase

| HDI_ref =[14]

| HDI_rank = 132nd

| currency = Indian rupee (₹)

| currency_code = INR

| time_zone = IST

| utc_offset = +05:30

| utc_offset_DST =

| DST_note = DST is not observed.

| time_zone_DST =

| date_format =

- dd-mm-yyyy[lower-alpha 6]

| drives_on = left[15] | calling_code = +91 | cctld = .in (others) | englishmotto="Truth Alone Triumphs"[4] | religion_year = 2011

| religion =

- 79.8% Hinduism

- 14.2% Islam

- 2.3% Christianity

- 1.7% Sikhism

- 0.7% Buddhism

- 0.4% Jainism

- 0.23% unaffiliated

- 0.65% other[16]

| official_website = | today = | iso3166code = IN }} India, officially the Republic of India (ISO: Bhārat Gaṇarājya),[17] India's land is megadiverse, with four biodiversity hotspots.[18] Its forest cover comprises 21.7% of its area.[19] India's wildlife, which has traditionally been viewed with tolerance in India's culture,[20] is supported among these forests, and elsewhere, in protected habitats.

Etymology

According to the Oxford English Dictionary (third edition 2009), the name "India" is derived from the Classical Latin India, a reference to South Asia and an uncertain region to its east. In turn the name "India" derived successively from Hellenistic Greek India ( Ἰνδία), ancient Greek Indos ( Ἰνδός), Old Persian Hindush (an eastern province of the Achaemenid Empire), and ultimately its cognate, the Sanskrit Sindhu, or "river", specifically the Indus River and, by implication, its well-settled southern basin.[21][22] The ancient Greeks referred to the Indians as Indoi (Ἰνδοί), which translates as "The people of the Indus".[23]

The term Bharat (Bhārat; pronounced [ˈbʱaːɾət] (![]() listen)), mentioned in both Indian epic poetry and the Constitution of India,[24][25] is used in its variations by many Indian languages. A modern rendering of the historical name Bharatavarsha, which applied originally to North India,[26][27] Bharat gained increased currency from the mid-19th century as a native name for India.[24][28]

listen)), mentioned in both Indian epic poetry and the Constitution of India,[24][25] is used in its variations by many Indian languages. A modern rendering of the historical name Bharatavarsha, which applied originally to North India,[26][27] Bharat gained increased currency from the mid-19th century as a native name for India.[24][28]

Hindustan ([ɦɪndʊˈstaːn] (![]() listen)) is a Middle Persian name for India that became popular by the 13th century,[29] and was used widely since the era of the Mughal Empire. The meaning of Hindustan has varied, referring to a region encompassing present-day northern India and Pakistan or to India in its near entirety.[24][28][30]

listen)) is a Middle Persian name for India that became popular by the 13th century,[29] and was used widely since the era of the Mughal Empire. The meaning of Hindustan has varied, referring to a region encompassing present-day northern India and Pakistan or to India in its near entirety.[24][28][30]

History

Ancient India

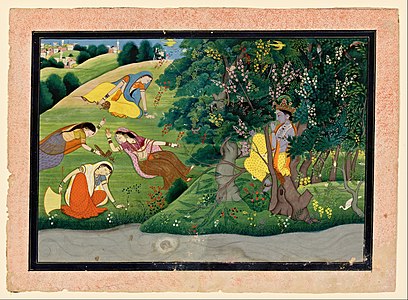

[[File:Battle at Lanka, Ramayana, Udaipur, 1649-53.jpg|thumb|Manuscript illustration, c. 1650, of the Sanskrit epic Ramayana, composed in story-telling fashion c. 400 BCE – c. 300 CECite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag Economic liberalisation, which began in the 1980s and the collaboration with Soviet Union for technical know-how,[31] has created a large urban middle class, transformed India into one of the world's fastest-growing economies,[32] and increased its geopolitical clout. Yet, India is also shaped by seemingly unyielding poverty, both rural and urban;[33] by religious and caste-related violence;[34] by Maoist-inspired Naxalite insurgencies;[35] and by separatism in Jammu and Kashmir and in Northeast India.[36] It has unresolved territorial disputes with China[37] and with Pakistan.[37] India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newer nations; however, in spite of its recent economic successes, freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains a goal yet to be achieved.[38]

Geography

India accounts for the bulk of the Indian subcontinent, lying atop the Indian tectonic plate, a part of the Indo-Australian Plate.[39] India's defining geological processes began 75 million years ago when the Indian Plate, then part of the southern supercontinent Gondwana, began a north-eastward drift caused by seafloor spreading to its south-west, and later, south and south-east.[39] Simultaneously, the vast Tethyan oceanic crust, to its northeast, began to subduct under the Eurasian Plate.[39] These dual processes, driven by convection in the Earth's mantle, both created the Indian Ocean and caused the Indian continental crust eventually to under-thrust Eurasia and to uplift the Himalayas.[39] Immediately south of the emerging Himalayas, plate movement created a vast crescent-shaped trough that rapidly filled with river-borne sediment[40] and now constitutes the Indo-Gangetic Plain.[41] The original Indian plate makes its first appearance above the sediment in the ancient Aravalli range, which extends from the Delhi Ridge in a southwesterly direction. To the west lies the Thar Desert, the eastern spread of which is checked by the Aravallis.[42][43][44]

The remaining Indian Plate survives as peninsular India, the oldest and geologically most stable part of India. It extends as far north as the Satpura and Vindhya ranges in central India. These parallel chains run from the Arabian Sea coast in Gujarat in the west to the coal-rich Chota Nagpur Plateau in Jharkhand in the east.[46] To the south, the remaining peninsular landmass, the Deccan Plateau, is flanked on the west and east by coastal ranges known as the Western and Eastern Ghats;[47] the plateau contains the country's oldest rock formations, some over one billion years old. Constituted in such fashion, India lies to the north of the equator between 6° 44′ and 35° 30′ north latitude[lower-alpha 7] and 68° 7′ and 97° 25′ east longitude.[48]

India's coastline measures 7,517 kilometres (4,700 mi) in length; of this distance, 5,423 kilometres (3,400 mi) belong to peninsular India and 2,094 kilometres (1,300 mi) to the Andaman, Nicobar, and Lakshadweep island chains.[49] According to the Indian naval hydrographic charts, the mainland coastline consists of the following: 43% sandy beaches; 11% rocky shores, including cliffs; and 46% mudflats or marshy shores.[49]

Major Himalayan-origin rivers that substantially flow through India include the Ganges and the Brahmaputra, both of which drain into the Bay of Bengal.[50] Important tributaries of the Ganges include the Yamuna and the Kosi; the latter's extremely low gradient, caused by long-term silt deposition, leads to severe floods and course changes.[51][52] Major peninsular rivers, whose steeper gradients prevent their waters from flooding, include the Godavari, the Mahanadi, the Kaveri, and the Krishna, which also drain into the Bay of Bengal;[53] and the Narmada and the Tapti, which drain into the Arabian Sea.[54] Coastal features include the marshy Rann of Kutch of western India and the alluvial Sundarbans delta of eastern India; the latter is shared with Bangladesh.[55] India has two archipelagos: the Lakshadweep, coral atolls off India's south-western coast; and the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, a volcanic chain in the Andaman Sea.[56]

Indian climate is strongly influenced by the Himalayas and the Thar Desert, both of which drive the economically and culturally pivotal summer and winter monsoons.[57] The Himalayas prevent cold Central Asian katabatic winds from blowing in, keeping the bulk of the Indian subcontinent warmer than most locations at similar latitudes.[58][59] The Thar Desert plays a crucial role in attracting the moisture-laden south-west summer monsoon winds that, between June and October, provide the majority of India's rainfall.[57] Four major climatic groupings predominate in India: tropical wet, tropical dry, subtropical humid, and montane.[60]

Temperatures in India have risen by 0.7 °C (1.3 °F) between 1901 and 2018.[61] Climate change in India is often thought to be the cause. The retreat of Himalayan glaciers has adversely affected the flow rate of the major Himalayan rivers, including the Ganges and the Brahmaputra.[62] According to some current projections, the number and severity of droughts in India will have markedly increased by the end of the present century.[63]

Biodiversity

India is a megadiverse country, a term employed for 17 countries which display high biological diversity and contain many species exclusively indigenous, or endemic, to them.[64] India is a habitat for 8.6% of all mammal species, 13.7% of bird species, 7.9% of reptile species, 6% of amphibian species, 12.2% of fish species, and 6.0% of all flowering plant species.[65][66] Fully a third of Indian plant species are endemic.[67] India also contains four of the world's 34 biodiversity hotspots,[18] or regions that display significant habitat loss in the presence of high endemism.[lower-alpha 8][68]

According to official statistics, India's forest cover is 713,789 km2 (275,595 sq mi), which is 21.71% of the country's total land area.[19] It can be subdivided further into broad categories of canopy density, or the proportion of the area of a forest covered by its tree canopy.[69] Very dense forest, whose canopy density is greater than 70%, occupies 3.02% of India's land area.[69][70] It predominates in the tropical moist forest of the Andaman Islands, the Western Ghats, and Northeast India. Moderately dense forest, whose canopy density is between 40% and 70%, occupies 9.39% of India's land area.[69][70] It predominates in the temperate coniferous forest of the Himalayas, the moist deciduous sal forest of eastern India, and the dry deciduous teak forest of central and southern India.[71] Open forest, whose canopy density is between 10% and 40%, occupies 9.26% of India's land area.[69][70] India has two natural zones of thorn forest, one in the Deccan Plateau, immediately east of the Western Ghats, and the other in the western part of the Indo-Gangetic plain, now turned into rich agricultural land by irrigation, its features no longer visible.[72]

Among the Indian subcontinent's notable indigenous trees are the astringent Azadirachta indica, or neem, which is widely used in rural Indian herbal medicine,[73] and the luxuriant Ficus religiosa, or peepul,[74] which is displayed on the ancient seals of Mohenjo-daro,[75] and under which the Buddha is recorded in the Pali canon to have sought enlightenment.[76]

Many Indian species have descended from those of Gondwana, the southern supercontinent from which India separated more than 100 million years ago.[77] India's subsequent collision with Eurasia set off a mass exchange of species. However, volcanism and climatic changes later caused the extinction of many endemic Indian forms.[78] Still later, mammals entered India from Asia through two zoogeographical passes flanking the Himalayas.[79] This had the effect of lowering endemism among India's mammals, which stands at 12.6%, contrasting with 45.8% among reptiles and 55.8% among amphibians.[66] Among endemics are the vulnerable[80] hooded leaf monkey[81] and the threatened[82] Beddome's toad[82][83] of the Western Ghats.

India contains 172 IUCN-designated threatened animal species, or 2.9% of endangered forms.[84] These include the endangered Bengal tiger and the Ganges river dolphin. Critically endangered species include the gharial, a crocodilian; the great Indian bustard; and the Indian white-rumped vulture, which has become nearly extinct by having ingested the carrion of diclofenac-treated cattle.[85] Before they were extensively used for agriculture and cleared for human settlement, the thorn forests of Punjab were mingled at intervals with open grasslands that were grazed by large herds of blackbuck preyed on by the Asiatic cheetah; the blackbuck, no longer extant in Punjab, is now severely endangered in India, and the cheetah is extinct.[86] The pervasive and ecologically devastating human encroachment of recent decades has critically endangered Indian wildlife. In response, the system of national parks and protected areas, first established in 1935, was expanded substantially. In 1972, India enacted the Wildlife Protection Act[87] and Project Tiger to safeguard crucial wilderness; the Forest Conservation Act was enacted in 1980 and amendments added in 1988.[88] India hosts more than five hundred wildlife sanctuaries and eighteen biosphere reserves,[89] four of which are part of the World Network of Biosphere Reserves; seventy-five wetlands are registered under the Ramsar Convention.[90]

A chital (Axis axis) stag in the Nagarhole National Park in a region covered by a moderately dense[lower-alpha 9] forest.

Three of the last Asiatic cheetahs in India were shot dead in 1948 in Surguja district, Madhya Pradesh, Central India by Maharajah Ramanuj Pratap Singh Deo. The young male cheetahs, all from the same litter, were sitting together when they were shot at night.

Politics and government

Politics

A parliamentary republic with a multi-party system,[93] India has six recognised national parties, including the Indian National Congress (INC) and the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), and more than 50 regional parties.[94] The Congress is considered centre-left in Indian political culture,[95] and the BJP right-wing.[96][97][98] For most of the period between 1950—when India first became a republic—and the late 1980s, the Congress held a majority in the Parliament. Since then, however, it has increasingly shared the political stage with the BJP,[99] as well as with powerful regional parties which have often forced the creation of multi-party coalition governments at the centre.[100]

In the Republic of India's first three general elections, in 1951, 1957, and 1962, the Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru-led Congress won easy victories. On Nehru's death in 1964, Lal Bahadur Shastri briefly became prime minister; he was succeeded, after his own unexpected death in 1966, by Nehru's daughter Indira Gandhi, who went on to lead the Congress to election victories in 1967 and 1971. Following public discontent with the state of emergency she declared in 1975, the Congress was voted out of power in 1977; the then-new Janata Party, which had opposed the emergency, was voted in. Its government lasted just over two years. There were two prime ministers during this period; Morarji Desai and Charan Singh. Voted back into power in 1980, the Congress saw a change in leadership in 1984, when Indira Gandhi was assassinated; she was succeeded by her son Rajiv Gandhi, who won an easy victory in the general elections later that year. The Congress was voted out again in 1989 when a National Front coalition, led by the newly formed Janata Dal in alliance with the Left Front, won the elections; that government too proved relatively short-lived, lasting just under two years. There were two prime ministers during this period; V.P. Singh and Chandra Shekhar.[101] Elections were held again in 1991; no party won an absolute majority. The Congress, as the largest single party, was able to form a minority government led by P. V. Narasimha Rao.[102]

A two-year period of political turmoil followed the general election of 1996. Several short-lived alliances shared power at the centre. The BJP formed a government briefly in 1996; it was followed by two comparatively long-lasting United Front coalitions, which depended on external support. There were two prime ministers during this period; H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral. In 1998, the BJP was able to form a successful coalition, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA). Led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, the NDA became the first non-Congress, coalition government to complete a five-year term.[103] Again in the 2004 Indian general elections, no party won an absolute majority, but the Congress emerged as the largest single party, forming another successful coalition: the United Progressive Alliance (UPA). It had the support of left-leaning parties and MPs who opposed the BJP. The UPA returned to power in the 2009 general election with increased numbers, and it no longer required external support from India's communist parties.[104] That year, Manmohan Singh became the first prime minister since Jawaharlal Nehru in 1957 and 1962 to be re-elected to a consecutive five-year term.[105] In the 2014 general election, the BJP became the first political party since 1984 to win a majority and govern without the support of other parties.[106] In the 2019 general election, the BJP was victorious again. The incumbent prime minister is Narendra Modi, a former chief minister of Gujarat. On 22 July 2022, Droupadi Murmu was elected India's 15th president and took the oath of office on 25 July 2022.[107]

Government

India is a federation with a parliamentary system governed under the Constitution of India—the country's supreme legal document. It is a constitutional republic.

Federalism in India defines the power distribution between the union and the states. The Constitution of India, which came into effect on 26 January 1950,[109] originally stated India to be a "sovereign, democratic republic;" this characterisation was amended in 1971 to "a sovereign, socialist, secular, democratic republic".[110] India's form of government, traditionally described as "quasi-federal" with a strong centre and weak states,[111] has grown increasingly federal since the late 1990s as a result of political, economic, and social changes.[112][113]

| Emblem | Sarnath Lion Capital |

|---|---|

| Anthem | Jana Gana Mana |

| Song | "Vande Mataram" |

| Language | None[114][115][116] |

| Currency | ₹ (Indian rupee) |

| Calendar | Shaka |

| Mammal | |

| Bird | Indian peafowl |

| Flower | Lotus |

| Fruit | Mango |

| Tree | Banyan |

| River | Ganges |

The Government of India comprises three branches:[117]

- Executive: The President of India is the ceremonial head of state,[118] who is elected indirectly for a five-year term by an electoral college comprising members of national and state legislatures.[119][120] The Prime Minister of India is the head of government and exercises most executive power.[121] Appointed by the president,[122] the prime minister is by convention supported by the party or political alliance having a majority of seats in the lower house of parliament.[121] The executive of the Indian government consists of the president, the vice-president, and the Union Council of Ministers—with the cabinet being its executive committee—headed by the prime minister. Any minister holding a portfolio must be a member of one of the houses of parliament.[118] In the Indian parliamentary system, the executive is subordinate to the legislature; the prime minister and their council are directly responsible to the lower house of the parliament. Civil servants act as permanent executives and all decisions of the executive are implemented by them.[123]

- Legislature: The legislature of India is the bicameral parliament. Operating under a Westminster-style parliamentary system, it comprises an upper house called the Rajya Sabha (Council of States) and a lower house called the Lok Sabha (House of the People).[124] The Rajya Sabha is a permanent body of 245 members who serve staggered six-year terms.[125] Most are elected indirectly by the state and union territorial legislatures in numbers proportional to their state's share of the national population.[122] All but two of the Lok Sabha's 545 members are elected directly by popular vote; they represent single-member constituencies for five-year terms.[126] Two seats of parliament, reserved for Anglo-Indians in the article 331, have been scrapped.[127][128]

- Judiciary: India has a three-tier unitary independent judiciary[129] comprising the supreme court, headed by the Chief Justice of India, 25 high courts, and a large number of trial courts.[129] The supreme court has original jurisdiction over cases involving fundamental rights and over disputes between states and the centre and has appellate jurisdiction over the high courts.[130] It has the power to both strike down union or state laws which contravene the constitution[131] and invalidate any government action it deems unconstitutional.[132]

Administrative divisions

India is a federal union comprising 28 states and 8 union territories.[11] All states, as well as the union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, Puducherry and the National Capital Territory of Delhi, have elected legislatures and governments following the Westminster system of governance. The remaining five union territories are directly ruled by the central government through appointed administrators. In 1956, under the States Reorganisation Act, states were reorganised on a linguistic basis.[133] There are over a quarter of a million local government bodies at city, town, block, district and village levels.[134]

States

Union territories

Foreign, economic and strategic relations

In the 1950s, India strongly supported decolonisation in Africa and Asia and played a leading role in the Non-Aligned Movement.[136] After initially cordial relations with neighbouring China, India went to war with China in 1962 and was widely thought to have been humiliated.[137] This was followed by another military conflict in 1967 in which India successfully repelled Chinese attack.[138] India has had tense relations with neighbouring Pakistan; the two nations have gone to war four times: in 1947, 1965, 1971, and 1999. Three of these wars were fought over the disputed territory of Kashmir, while the third, the 1971 war, followed from India's support for the independence of Bangladesh.[139] In the late 1980s, the Indian military twice intervened abroad at the invitation of the host country: a peace-keeping operation in Sri Lanka between 1987 and 1990; and an armed intervention to prevent a 1988 coup d'état attempt in the Maldives. After the 1965 war with Pakistan, India began to pursue close military and economic ties with the Soviet Union; by the late 1960s, the Soviet Union was its largest arms supplier.[140]

Aside from its ongoing special relationship with Russia,[141] India has wide-ranging defence relations with Israel and France. In recent years, it has played key roles in the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation and the World Trade Organization. The nation has provided 100,000 military and police personnel to serve in 35 UN peacekeeping operations across four continents. It participates in the East Asia Summit, the G8+5, and other multilateral forums.[142] India has close economic ties with countries in South America,[143] Asia, and Africa; it pursues a "Look East" policy that seeks to strengthen partnerships with the ASEAN nations, Japan, and South Korea that revolve around many issues, but especially those involving economic investment and regional security.[144][145]

China's nuclear test of 1964, as well as its repeated threats to intervene in support of Pakistan in the 1965 war, convinced India to develop nuclear weapons.[147] India conducted its first nuclear weapons test in 1974 and carried out additional underground testing in 1998. Despite criticism and military sanctions, India has signed neither the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty nor the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, considering both to be flawed and discriminatory.[148] India maintains a "no first use" nuclear policy and is developing a nuclear triad capability as a part of its "Minimum Credible Deterrence" doctrine.[149][150] It is developing a ballistic missile defence shield and, a fifth-generation fighter jet.[151][152] Other indigenous military projects involve the design and implementation of Vikrant-class aircraft carriers and Arihant-class nuclear submarines.[153]

Since the end of the Cold War, India has increased its economic, strategic, and military co-operation with the United States and the European Union.[154] In 2008, a civilian nuclear agreement was signed between India and the United States. Although India possessed nuclear weapons at the time and was not a party to the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, it received waivers from the International Atomic Energy Agency and the Nuclear Suppliers Group, ending earlier restrictions on India's nuclear technology and commerce. As a consequence, India became the sixth de facto nuclear weapons state.[155] India subsequently signed co-operation agreements involving civilian nuclear energy with Russia,[156] France,[157] the United Kingdom,[158] and Canada.[159]

The President of India is the supreme commander of the nation's armed forces; with 1.45 million active troops, they compose the world's second-largest military. It comprises the Indian Army, the Indian Navy, the Indian Air Force, and the Indian Coast Guard.[160] The official Indian defence budget for 2011 was US$36.03 billion, or 1.83% of GDP.[161] Defence expenditure was pegged at US$70.12 billion for fiscal year 2022–23 and, increased 9.8% than previous fiscal year.[162][163] India is the world's second-largest arms importer; between 2016 and 2020, it accounted for 9.5% of the total global arms imports.[164] Much of the military expenditure was focused on defence against Pakistan and countering growing Chinese influence in the Indian Ocean.[165] In May 2017, the Indian Space Research Organisation launched the South Asia Satellite, a gift from India to its neighbouring SAARC countries.[166] In October 2018, India signed a US$5.43 billion (over ₹400 billion) agreement with Russia to procure four S-400 Triumf surface-to-air missile defence systems, Russia's most advanced long-range missile defence system.[167]

Economy

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Indian economy in 2022 was nominally worth $3.46 trillion; it was the fifth-largest economy by market exchange rates and is, around $11.6 trillion, the third-largest by purchasing power parity (PPP).[171] With its average annual GDP growth rate of 5.8% over the past two decades, and reaching 6.1% during 2011–2012,[172] India is one of the world's fastest-growing economies.[173] However, the country ranks 139th in the world in nominal GDP per capita and 118th in GDP per capita at PPP.[174] Until 1991, all Indian governments followed protectionist policies that were influenced by socialist economics. Widespread state intervention and regulation largely walled the economy off from the outside world. An acute balance of payments crisis in 1991 forced the nation to liberalise its economy;[175] since then, it has moved increasingly towards a free-market system[176][177] by emphasising both foreign trade and direct investment inflows.[178] India has been a member of World Trade Organization since 1 January 1995.[179]

The 522-million-worker Indian labour force is the world's second-largest, as of 2017[update].[160] The service sector makes up 55.6% of GDP, the industrial sector 26.3% and the agricultural sector 18.1%. India's foreign exchange remittances of US$100 billion in 2022,[180] highest in the world, were contributed to its economy by 32 million Indians working in foreign countries.[181] Major agricultural products include rice, wheat, oilseed, cotton, jute, tea, sugarcane, and potatoes.[11] Major industries include textiles, telecommunications, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, food processing, steel, transport equipment, cement, mining, petroleum, machinery, and software.[11] In 2006, the share of external trade in India's GDP stood at 24%, up from 6% in 1985.[176] In 2008, India's share of world trade was 1.68%;[182] In 2021, India was the world's ninth-largest importer and the sixteenth-largest exporter.[183] Major exports include petroleum products, textile goods, jewellery, software, engineering goods, chemicals, and manufactured leather goods.[11] Major imports include crude oil, machinery, gems, fertiliser, and chemicals.[11] Between 2001 and 2011, the contribution of petrochemical and engineering goods to total exports grew from 14% to 42%.[184] India was the world's second-largest textile exporter after China in the 2013 calendar year.[185]

Averaging an economic growth rate of 7.5% for several years prior to 2007,[176] India has more than doubled its hourly wage rates during the first decade of the 21st century.[186] Some 431 million Indians have left poverty since 1985; India's middle classes are projected to number around 580 million by 2030.[187] Though ranking 68th in global competitiveness,[188] as of 2010[update], India ranks 17th in financial market sophistication, 24th in the banking sector, 44th in business sophistication, and 39th in innovation, ahead of several advanced economies.[189] With seven of the world's top 15 information technology outsourcing companies based in India, as of 2009[update], the country is viewed as the second-most favourable outsourcing destination after the United States.[190] India is ranked 40th in the Global Innovation Index in 2022.[191] India's consumer market, the world's eleventh-largest,Template:As of? is expected to become fifth-largest by 2030.[187]

Driven by growth, India's nominal GDP per capita increased steadily from US$308 in 1991, when economic liberalisation began, to US$1,380 in 2010, to an estimated US$1,730 in 2016. It is expected to grow to US$2,466 by 2022.[12] However, it has remained lower than those of other Asian developing countries such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Sri Lanka, and Thailand, and is expected to remain so in the near future.

According to a 2011 PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) report, India's GDP at purchasing power parity could overtake that of the United States by 2045.[193] During the next four decades, Indian GDP is expected to grow at an annualised average of 8%, making it potentially the world's fastest-growing major economy until 2050.[193] The report highlights key growth factors: a young and rapidly growing working-age population; growth in the manufacturing sector because of rising education and engineering skill levels; and sustained growth of the consumer market driven by a rapidly growing middle-class.[193] The World Bank cautions that, for India to achieve its economic potential, it must continue to focus on public sector reform, transport infrastructure, agricultural and rural development, removal of labour regulations, education, energy security, and public health and nutrition.[194]

According to the Worldwide Cost of Living Report 2017 released by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) which was created by comparing more than 400 individual prices across 160 products and services, four of the cheapest cities were in India: Bangalore (3rd), Mumbai (5th), Chennai (5th) and New Delhi (8th).[195]

Industries

India's telecommunication industry is the second-largest in the world with over 1.2 billion subscribers. It contributes 6.5% to India's GDP.[196] After the third quarter of 2017, India surpassed the US to become the second-largest smartphone market in the world after China.[197]

The Indian automotive industry, the world's second-fastest growing, increased domestic sales by 26% during 2009–2010,[198] and exports by 36% during 2008–2009.[199] In 2022, India became the world's third-largest vehicle market after China and the United States, surpassing Japan.[200] At the end of 2011, the Indian IT industry employed 2.8 million professionals, generated revenues close to US$100 billion equalling 7.5% of Indian GDP, and contributed 26% of India's merchandise exports.[201]

The pharmaceutical industry in India emerged as a global player. As of 2021, with 3000 pharmaceutical companies and 10,500 manufacturing units India is the world's third-largest pharmaceutical producer, largest producer of generic medicines and supply up to 50—60% of global vaccines demand, these all contribute up to US$24.44 billions in exports and India's local pharmaceutical market is estimated up to US$42 billion.[202][203] India is among the top 12 biotech destinations in the world.[204][205] The Indian biotech industry grew by 15.1% in 2012–2013, increasing its revenues from ₹204.4 billion (Indian rupees) to ₹235.24 billion (US$3.94 billion at June 2013 exchange rates).[206]

Energy

India's capacity to generate electrical power is 300 gigawatts, of which 42 gigawatts is renewable.[207] The country's usage of coal is a major cause of greenhouse gas emissions by India but its renewable energy is competing strongly.[208] India emits about 7% of global greenhouse gas emissions. This equates to about 2.5 tons of carbon dioxide per person per year, which is half the world average.[209][210] Increasing access to electricity and clean cooking with liquefied petroleum gas have been priorities for energy in India.[211]

Socio-economic challenges

Despite economic growth during recent decades, India continues to face socio-economic challenges. In 2006, India contained the largest number of people living below the World Bank's international poverty line of US$1.25 per day.[213] The proportion decreased from 60% in 1981 to 42% in 2005.[214] Under the World Bank's later revised poverty line, it was 21% in 2011.[lower-alpha 10][216] 30.7% of India's children under the age of five are underweight.[217] According to a Food and Agriculture Organization report in 2015, 15% of the population is undernourished.[218][219] The Mid-Day Meal Scheme attempts to lower these rates.[220]

A 2018 Walk Free Foundation report estimated that nearly 8 million people in India were living in different forms of modern slavery, such as bonded labour, child labour, human trafficking, and forced begging, among others.[221] According to the 2011 census, there were 10.1 million child labourers in the country, a decline of 2.6 million from 12.6 million in 2001.[222]

Since 1991, economic inequality between India's states has consistently grown: the per-capita net state domestic product of the richest states in 2007 was 3.2 times that of the poorest.[223] Corruption in India is perceived to have decreased. According to the Corruption Perceptions Index, India ranked 78th out of 180 countries in 2018 with a score of 41 out of 100, an improvement from 85th in 2014.[224][225]

Epidemic and pandemic diseases have long been a major factor, including COVID-19 recently.[226]

Demographics, languages and religion

With 1,210,193,422 residents reported in the 2011 provisional census report,[227] India was the world's second-most populous country.[lower-alpha 11] Its population grew by 17.64% from 2001 to 2011,[229] compared to 21.54% growth in the previous decade (1991–2001).[229] The human sex ratio, according to the 2011 census, is 940 females per 1,000 males.[227] The median age was 28.7 as of 2020[update].[160] The first post-colonial census, conducted in 1951, counted 361 million people.[230] Medical advances made in the last 50 years as well as increased agricultural productivity brought about by the "Green Revolution" have caused India's population to grow rapidly.[231]

The life expectancy in India is at 70 years—71.5 years for women, 68.7 years for men.[160] There are around 93 physicians per 100,000 people.[232] Migration from rural to urban areas has been an important dynamic in India's recent history. The number of people living in urban areas grew by 31.2% between 1991 and 2001.[233] Yet, in 2001, over 70% still lived in rural areas.[234][235] The level of urbanisation increased further from 27.81% in the 2001 Census to 31.16% in the 2011 Census. The slowing down of the overall population growth rate was due to the sharp decline in the growth rate in rural areas since 1991.[236] According to the 2011 census, there are 53 million-plus urban agglomerations in India; among them Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Ahmedabad, in decreasing order by population.[237] The literacy rate in 2011 was 74.04%: 65.46% among females and 82.14% among males.[238] The rural-urban literacy gap, which was 21.2 percentage points in 2001, dropped to 16.1 percentage points in 2011. The improvement in the rural literacy rate is twice that of urban areas.[236] Kerala is the most literate state with 93.91% literacy; while Bihar the least with 63.82%.[238]

Among speakers of the Indian languages, 74% speak Indo-Aryan languages, the easternmost branch of the Indo-European languages; 24% speak Dravidian languages, indigenous to South Asia and spoken widely before the spread of Indo-Aryan languages and 2% speak Austroasiatic languages or the Sino-Tibetan languages. India has no national language.[239] Hindi, with the largest number of speakers, is the official language of the government.[240][241] English is used extensively in business and administration and has the status of a "subsidiary official language";[5] it is important in education, especially as a medium of higher education. Each state and union territory has one or more official languages, and the constitution recognises in particular 22 "scheduled languages".

The 2011 census reported the religion in India with the largest number of followers was Hinduism (79.80% of the population), followed by Islam (14.23%); the remaining were Christianity (2.30%), Sikhism (1.72%), Buddhism (0.70%), Jainism (0.36%) and others[lower-alpha 12] (0.9%).[16] India has the third-largest Muslim population—the largest for a non-Muslim majority country.[242][243]

Culture

Indian cultural history spans more than 4,500 years.[244] During the Vedic period (c. 1700 BCE – c. 500 BCE), the foundations of Hindu philosophy, mythology, theology and literature were laid, and many beliefs and practices which still exist today, such as dhárma, kárma, yóga, and mokṣa, were established.[23] India is notable for its religious diversity, with Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikhism, Islam, Christianity, and Jainism among the nation's major religions.[245] The predominant religion, Hinduism, has been shaped by various historical schools of thought, including those of the Upanishads,[246] the Yoga Sutras, the Bhakti movement,[245] and by Buddhist philosophy.[247]

Visual art

India has a very ancient tradition of art, which has exchanged many influences with the rest of Eurasia, especially in the first millennium, when Buddhist art spread with Indian religions to Central, East and South-East Asia, the last also greatly influenced by Hindu art.[248] Thousands of seals from the Indus Valley Civilization of the third millennium BCE have been found, usually carved with animals, but a few with human figures. The "Pashupati" seal, excavated in Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan, in 1928–29, is the best known.[249][250] After this there is a long period with virtually nothing surviving.[250][251] Almost all surviving ancient Indian art thereafter is in various forms of religious sculpture in durable materials, or coins. There was probably originally far more in wood, which is lost. In north India Mauryan art is the first imperial movement.[252][253][254] In the first millennium CE, Buddhist art spread with Indian religions to Central, East and South-East Asia, the last also greatly influenced by Hindu art.[255] Over the following centuries a distinctly Indian style of sculpting the human figure developed, with less interest in articulating precise anatomy than ancient Greek sculpture but showing smoothly flowing forms expressing prana ("breath" or life-force).[256][257] This is often complicated by the need to give figures multiple arms or heads, or represent different genders on the left and right of figures, as with the Ardhanarishvara form of Shiva and Parvati.[258][259]

Most of the earliest large sculpture is Buddhist, either excavated from Buddhist stupas such as Sanchi, Sarnath and Amaravati,[260] or is rock cut reliefs at sites such as Ajanta, Karla and Ellora. Hindu and Jain sites appear rather later.[261][262] In spite of this complex mixture of religious traditions, generally, the prevailing artistic style at any time and place has been shared by the major religious groups, and sculptors probably usually served all communities.[263] Gupta art, at its peak c. 300 CE – c. 500 CE, is often regarded as a classical period whose influence lingered for many centuries after; it saw a new dominance of Hindu sculpture, as at the Elephanta Caves.[264][265] Across the north, this became rather stiff and formulaic after c. 800 CE, though rich with finely carved detail in the surrounds of statues.[266] But in the South, under the Pallava and Chola dynasties, sculpture in both stone and bronze had a sustained period of great achievement; the large bronzes with Shiva as Nataraja have become an iconic symbol of India.[267][268]

Ancient painting has only survived at a few sites, of which the crowded scenes of court life in the Ajanta Caves are by far the most important, but it was evidently highly developed, and is mentioned as a courtly accomplishment in Gupta times.[269][270] Painted manuscripts of religious texts survive from Eastern India about the 10th century onwards, most of the earliest being Buddhist and later Jain. No doubt the style of these was used in larger paintings.[271] The Persian-derived Deccan painting, starting just before the Mughal miniature, between them give the first large body of secular painting, with an emphasis on portraits, and the recording of princely pleasures and wars.[272][273] The style spread to Hindu courts, especially among the Rajputs, and developed a variety of styles, with the smaller courts often the most innovative, with figures such as Nihâl Chand and Nainsukh.[274][275] As a market developed among European residents, it was supplied by Company painting by Indian artists with considerable Western influence.[276][277] In the 19th century, cheap Kalighat paintings of gods and everyday life, done on paper, were urban folk art from Calcutta, which later saw the Bengal School of Art, reflecting the art colleges founded by the British, the first movement in modern Indian painting.[278][279]

Bhutesvara Yakshis, Buddhist reliefs from Mathura, 2nd century CE

Gupta terracotta relief, Krishna Killing the Horse Demon Keshi, 5th century

Elephanta Caves, triple-bust (trimurti) of Shiva, 18 feet (5.5 m) tall, c. 550

Chola bronze of Shiva as Nataraja ("Lord of Dance"), Tamil Nadu, 10th or 11th century

Jahangir Receives Prince Khurram at Ajmer on His Return from the Mewar Campaign, Balchand, c. 1635

Krishna Fluting to the Milkmaids, Kangra painting, 1775–1785

Architecture

Much of Indian architecture, including the Taj Mahal, other works of Indo-Islamic Mughal architecture, and South Indian architecture, blends ancient local traditions with imported styles.[280] Vernacular architecture is also regional in its flavours. Vastu shastra, literally "science of construction" or "architecture" and ascribed to Mamuni Mayan,[281] explores how the laws of nature affect human dwellings;[282] it employs precise geometry and directional alignments to reflect perceived cosmic constructs.[283] As applied in Hindu temple architecture, it is influenced by the Shilpa Shastras, a series of foundational texts whose basic mythological form is the Vastu-Purusha mandala, a square that embodied the "absolute".[284] The Taj Mahal, built in Agra between 1631 and 1648 by orders of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan in memory of his wife, has been described in the UNESCO World Heritage List as "the jewel of Muslim art in India and one of the universally admired masterpieces of the world's heritage".[285] Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, developed by the British in the late 19th century, drew on Indo-Islamic architecture.[286]

Literature

The earliest literature in India, composed between 1500 BCE and 1200 CE, was in the Sanskrit language.[287] Major works of Sanskrit literature include the Rigveda (c. 1500 BCE – c. 1200 BCE), the epics: Mahābhārata (c. 400 BCE – c. 400 CE) and the Ramayana (c. 300 BCE and later); Abhijñānaśākuntalam (The Recognition of Śakuntalā, and other dramas of Kālidāsa (c. 5th century CE) and Mahākāvya poetry.[288][289][290] In Tamil literature, the Sangam literature (c. 600 BCE – c. 300 BCE) consisting of 2,381 poems, composed by 473 poets, is the earliest work.[291][292][293][294] From the 14th to the 18th centuries, India's literary traditions went through a period of drastic change because of the emergence of devotional poets like Kabīr, Tulsīdās, and Guru Nānak. This period was characterised by a varied and wide spectrum of thought and expression; as a consequence, medieval Indian literary works differed significantly from classical traditions.[295] In the 19th century, Indian writers took a new interest in social questions and psychological descriptions. In the 20th century, Indian literature was influenced by the works of the Bengali poet, author and philosopher Rabindranath Tagore,[296] who was a recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Performing arts and media

Indian music ranges over various traditions and regional styles. Classical music encompasses two genres and their various folk offshoots: the northern Hindustani and the southern Carnatic schools.[297] Regionalised popular forms include filmi and folk music; the syncretic tradition of the bauls is a well-known form of the latter. Indian dance also features diverse folk and classical forms. Among the better-known folk dances are: bhangra of Punjab, bihu of Assam, Jhumair and chhau of Jharkhand, Odisha and West Bengal, garba and dandiya of Gujarat, ghoomar of Rajasthan, and lavani of Maharashtra. Eight dance forms, many with narrative forms and mythological elements, have been accorded classical dance status by India's National Academy of Music, Dance, and Drama. These are: bharatanatyam of the state of Tamil Nadu, kathak of Uttar Pradesh, kathakali and mohiniyattam of Kerala, kuchipudi of Andhra Pradesh, manipuri of Manipur, odissi of Odisha, and the sattriya of Assam.[298]

Theatre in India melds music, dance, and improvised or written dialogue.[299] Often based on Hindu mythology, but also borrowing from medieval romances or social and political events, Indian theatre includes: the bhavai of Gujarat, the jatra of West Bengal, the nautanki and ramlila of North India, tamasha of Maharashtra, burrakatha of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, terukkuttu of Tamil Nadu, and the yakshagana of Karnataka.[300] India has a theatre training institute the National School of Drama (NSD) that is situated at New Delhi. It is an autonomous organisation under the Ministry of culture, Government of India.[301]

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2006), A Concise History of Modern India (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-68225-1

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (2012), A Concise History of Modern India, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-107-02649-0

- Peers, D. M. (2006), India under Colonial Rule: 1700–1885, Pearson Longman, ISBN 978-0-582-31738-3

- Peers, D. M. (2013), India Under Colonial Rule: 1700–1885, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-88286-2, retrieved 13 August 2019

- Petraglia, Michael D.; Allchin, Bridget (2007), "Human evolution and culture change in the Indian subcontinent", in Michael Petraglia; Bridget Allchin (eds.), The Evolution and History of Human Populations in South Asia: Inter-disciplinary Studies in Archaeology, Biological Anthropology, Linguistics and Genetics, Springer Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4020-5562-1

- Possehl, G. (2003), The Indus Civilization: A Contemporary Perspective, Rowman Altamira, ISBN 978-0-7591-0172-2

- Robb, P. (2001), A History of India, Palgrave, ISBN 978-0-333-69129-8

- Robb, P. (2011), A History of India, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-230-34549-2

- Sarkar, S. (1983), Modern India: 1885–1947, Delhi: Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-90425-1

- Singh, Upinder (2009), A History of Ancient and Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century, Delhi: Longman, ISBN 978-81-317-1677-9

- Singh, Upinder (2017), Political Violence in Ancient India, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-98128-7

- Sripati, V. (1998), "Toward Fifty Years of Constitutionalism and Fundamental Rights in India: Looking Back to See Ahead (1950–2000)", American University International Law Review, 14 (2): 413–496

- Stein, B. (1998), A History of India, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-0-631-20546-3

- Stein, B. (2010), Arnold, D. (ed.), A History of India (2nd ed.), Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4051-9509-6

- Witzel, Michael (2003), "Vedas and Upanișads", in Gavin D. Flood (ed.), The Blackwell companion to Hinduism, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-631-21535-6, retrieved 15 March 2012

- Wolpert, S. (2003), A New History of India (7th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-516678-1

Geography

- Ali, J. R.; Aitchison, J. C. (2005), "Greater India", Earth-Science Reviews, 72 (3–4): 170–173, Bibcode:2005ESRv...72..169A, doi:10.1016/j.earscirev.2005.07.005

- Basu, Mahua; Xavier, Savarimuthu (2017), Fundamentals of Environmental Studies, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-1-316-87051-8

- Chang, J. H. (1967), "The Indian Summer Monsoon", Geographical Review, American Geographical Society, Wiley, vol. 57, no. 3, pp. 373–396, doi:10.2307/212640, JSTOR 212640

- Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980 with Amendments Made in 1988 (PDF), Department of Environment and Forests, Government of the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 1988, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 July 2011, retrieved 25 July 2011

- Dikshit, K. R.; Schwartzberg, Joseph E. (2023), "India: Land", Encyclopædia Britannica, pp. 1–29

- Duff, D. (1993), Holmes Principles of Physical Geology (4th ed.), Routledge, ISBN 978-0-7487-4381-0

- Kaul, R. N. (1970), "The Indian Subcontinent: Indo-Pakistan", in Kaul, R. N. (ed.), Afforestation in Arid Zones, The Hague: Dr. W. Junk, N.V., Publishers, ISBN 978-94-010-3352-7

- Kumar, V. Sanil; Pathak, K. C.; Pednekar, P.; Raju, N. S. N.; Gowthaman, R. (2006), "Coastal processes along the Indian coastline" (PDF), Current Science, vol. 91, no. 4, pp. 530–536, archived from the original (PDF) on 8 September 2009

- Mcgrail, Sean; Blue, Lucy; Kentley, Eric; Palmer, Colin (2003), Boats of South Asia, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-43130-4

- India Yearbook 2007, New Delhi: Publications Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India, 2007, ISBN 978-81-230-1423-4

- Posey, C. A. (1994), The Living Earth Book of Wind and Weather, Reader's Digest, ISBN 978-0-89577-625-9

- Prakash, B.; Kumar, S.; Rao, M. S.; Giri, S. C. (2000), "Holocene Tectonic Movements and Stress Field in the Western Gangetic Plains" (PDF), Current Science, 79 (4): 438–449

- Prasad, Ishwar (1974), "The Ecology of Vertebrates of the Indian Desert", in Mani, M. S. (ed.), Ecology and Biogeography in India, The Hague: Dr. W. Junk bv Publishers, ISBN 978-94-010-2333-7

Biodiversity

- Basak, R. K. (1983), Botanical Survey of India: Account of Its Establishment, Development, and Activities, India. Department of Environment, retrieved 20 July 2011

- Crame, J. A.; Owen, A. W. (2002), Palaeobiogeography and Biodiversity Change: The Ordovician and Mesozoic–Cenozoic Radiations, Geological Society Special Publication, Geological Society of London, ISBN 978-1-86239-106-2, retrieved 8 December 2011

- Karanth, K. Ullas; Gopal, Rajesh (2005), "An ecology-based policy framework for human-tiger coexistence in India", in Rosie Woodroffe; Simon Thirgood; Alan Rabinowitz (eds.), People and Wildlife, Conflict Or Co-existence?, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-53203-7

- Karanth, K. P. (2006), "Out-of-India Gondwanan Origin of Some Tropical Asian Biota" (PDF), Current Science, 90 (6): 789–792, archived from the original (PDF) on 11 April 2019, retrieved 18 May 2011

- Mace, G. M. (1994), "1994 IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals", World Conservation Monitoring Centre, International Union for Conservation of Nature, ISBN 978-2-8317-0194-3

- Tritsch, M. F. (2001), Wildlife of India, London: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-00-711062-9

- "Biosphere Reserves of India", C. P. R. Environment Education Centre, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, archived from the original on 25 July 2011, retrieved 17 July 2011

- Indian Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972, Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India, 9 September 1972, retrieved 25 July 2011

- The List of Wetlands of International Importance (PDF), The Secretariat of the Convention on Wetlands, 4 June 2007, p. 18, archived from the original (PDF) on 21 June 2007, retrieved 20 June 2007

Politics

- Banerjee, Sumanta (22 July 2005). "Civilising the BJP". Economic & Political Weekly. 40 (29): 3116–3119. JSTOR 4416896.

- Bhambhri, C. P. (1992), Politics in India, 1991–1992, Shipra, ISBN 978-81-85402-17-8, retrieved 20 July 2011

- Burnell, P. J.; Calvert, P. (1999), The Resilience of Democracy: Persistent Practice, Durable Idea, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-7146-8026-2, retrieved 20 July 2011

- India, Press Trust of (16 May 2009), "Second UPA Win, A Crowning Glory for Sonia's Ascendancy", Business Standard India, Press Trust of India, retrieved 13 June 2009

- Chander, N. J. (2004), Coalition Politics: The Indian Experience, Concept Publishing Company, ISBN 978-81-8069-092-1, retrieved 20 July 2011

- Dunleavy, P.; Diwakar, R.; Dunleavy, C. (2007), The Effective Space of Party Competition (PDF), London School of Economics and Political Science, archived from the original (PDF) on 28 October 2007, retrieved 27 September 2011

- Dutt, S. (1998), "Identities and the Indian State: An Overview", Third World Quarterly, 19 (3): 411–434, doi:10.1080/01436599814325

- Echeverri-Gent, J. (January 2002), "Politics in India's Decentred Polity", in Ayres, A.; Oldenburg, P. (eds.), Quickening the Pace of Change, India Briefing, London: M. E. Sharpe, pp. 19–53, ISBN 978-0-7656-0812-3

- "Current Recognised Parties" (PDF), Election Commission of India, 14 March 2009, retrieved 5 July 2010

- Gledhill, A. (1970), The Republic of India: The Development of its Laws and Constitution, Greenwood, ISBN 978-0-8371-2813-9, retrieved 21 July 2011

- Malik, Yogendra K.; Singh, V. B. (April 1992). "Bharatiya Janata Party: An Alternative to the Congress (I)?". Asian Survey. 32 (4): 318–336. doi:10.2307/2645149. JSTOR 2645149.

- Mathew, K. M. (2003), Manorama Yearbook, Malayala Manorama, ISBN 978-81-900461-8-3, retrieved 21 July 2011

- "National Symbols", Know India, National Informatics Centre, Government of India, archived from the original on 18 April 2021, retrieved 18 April 2021

- Neuborne, Burt (2003), "The Supreme Court of India", International Journal of Constitutional Law, 1 (3): 476–510, doi:10.1093/icon/1.3.476

- Pylee, M. V. (2003a), "The Longest Constitutional Document", Constitutional Government in India (2nd ed.), S. Chand, ISBN 978-81-219-2203-6

- Pylee, M. V. (2003b), "The Union Judiciary: The Supreme Court", Constitutional Government in India (2nd ed.), S. Chand, ISBN 978-81-219-2203-6, retrieved 2 November 2007

- Sarkar, N. I. (2007), Sonia Gandhi: Tryst with India, Atlantic, ISBN 978-81-269-0744-1, retrieved 20 July 2011

- Sharma, R. (1950), "Cabinet Government in India", Parliamentary Affairs, 4 (1): 116–126, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.pa.a052755

- Sharma, B. K. (2007), Introduction to the Constitution of India (4th ed.), Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-81-203-3246-1

- Sinha, A. (2004), "The Changing Political Economy of Federalism in India", India Review, 3 (1): 25–63, doi:10.1080/14736480490443085, S2CID 154543286

- World's Largest Democracy to Reach One Billion Persons on Independence Day, United Nations Population Division, retrieved 5 October 2011

- Wheare, K. C. (1980), Federal Government (4th ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-313-22702-8

Foreign relations and military

- Alford, P. (7 July 2008), "G8 Plus 5 Equals Power Shift", The Australian, retrieved 21 November 2009

- Behera, L. K. (7 March 2011), Budgeting for India's Defence: An Analysis of Defence Budget 2011–2012, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, retrieved 4 April 2011

- Behera, L. K. (20 March 2012), India's Defence Budget 2012–13, Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, archived from the original on 15 December 2012, retrieved 26 March 2012

- "Russia Agrees India Nuclear Deal", BBC News, BBC, 11 February 2009, retrieved 22 August 2010

- Curry, B. (27 June 2010), "Canada Signs Nuclear Deal with India", The Globe and Mail, archived from the original on 25 May 2017, retrieved 13 May 2011

- "EU-India Strategic Partnership", Europa: Summaries of EU Legislation, European Union, 8 April 2008, archived from the original on 3 May 2011, retrieved 14 January 2011

- Ghosh, A. (2009), India's Foreign Policy, Pearson, ISBN 978-81-317-1025-8

- Gilbert, M. (2002), A History of the Twentieth Century, William Morrow, ISBN 978-0-06-050594-3, retrieved 22 July 2011

- Kumar, A. V. (1 May 2010), "Reforming the NPT to Include India", Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, archived from the original on 7 April 2014, retrieved 1 November 2010

- Miglani, S. (28 February 2011), "With An Eye on China, India Steps Up Defence Spending", Reuters, archived from the original on 2 May 2011, retrieved 6 July 2011

- Nair, V. K. (2007), "No More Ambiguity: India's Nuclear Policy" (PDF), afsa.org, archived from the original (PDF) on 27 September 2007, retrieved 7 June 2007

- Pandit, Rajat (27 July 2009), "N-Submarine to Give India Crucial Third Leg of Nuke Triad", The Times of India, archived from the original on 11 August 2011, retrieved 10 March 2010

- Pandit, Rajat (8 January 2015), "Make-in-India: Plan to develop 5th-generation fighter aircraft", The Times of India, archived from the original on 11 March 2015, retrieved 17 October 2021

- Pandit, Rajat (16 March 2021). "India's weapon imports fell by 33% in last five years but remains world's second-largest arms importer". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Pandit, Rajat (1 February 2022). "Strong push for indigenous weapons amidst modest hike in defence budget". The Times of India. Retrieved 3 February 2022.

- Perkovich, G. (2001), India's Nuclear Bomb: The Impact on Global Proliferation, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-23210-5, retrieved 22 July 2011

- India, France Agree on Civil Nuclear Cooperation, Rediff, 25 January 2008, retrieved 22 August 2010

- "UK, India Sign Civil Nuclear Accord", Reuters, 13 February 2010, archived from the original on 12 May 2012, retrieved 22 August 2010

- Rothermund, D. (2000), The Routledge Companion to Decolonization, Routledge Companions to History, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-35632-9

- Sharma, S. R. (1999), India–USSR Relations 1947–1971: From Ambivalence to Steadfastness, vol. 1, Discovery, ISBN 978-81-7141-486-4

- Shukla, A. (5 March 2011), "China Matches India's Expansion in Military Spending", Business Standard India, retrieved 6 July 2011

- Sisodia, N. S.; Naidu, G. V. C. (2005), Changing Security Dynamic in Eastern Asia: Focus on Japan, Promilla, ISBN 978-81-86019-52-8

- "SIPRI Yearbook 2008: Armaments, Disarmament, and International Security", Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, Oxford University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-19-954895-8, retrieved 22 July 2011

- "Rise in international arms transfers is driven by Asian demand, says SIPRI", Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, 19 March 2012, retrieved 5 April 2016

- "India, US Sign 123 Agreement", The Times of India, 11 October 2008, archived from the original on 7 November 2011, retrieved 21 July 2011

Economy

- Alamgir, J. (2008), India's Open-Economy Policy: Globalism, Rivalry, Continuity, Taylor & Francis, ISBN 978-0-415-77684-4, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Bonner, B (20 March 2010), "Make Way, World. India Is on the Move", The Christian Science Monitor, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Farrell, D.; Beinhocker, E. (19 May 2007), Next Big Spenders: India's Middle Class, McKinsey & Company, archived from the original on 5 December 2011, retrieved 17 September 2011

- Gargan, E. A. (15 August 1992), "India Stumbles in Rush to a Free Market Economy", The New York Times, retrieved 22 July 2011

- Hawksworth, John; Tiwari, Anmol (January 2011), The World in 2050: The Accelerating Shift of Global Economic Power: Challenges and Opportunities (PDF), PricewaterhouseCoopers, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Nayak, P. B.; Goldar, B.; Agrawal, P. (2010), India's Economy and Growth: Essays in Honour of V. K. R. V. Rao, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-81-321-0452-0

- Pal, P.; Ghosh, J (July 2007), "Inequality in India: A Survey of Recent Trends" (PDF), DESA Working Paper No. 45, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Schwab, K. (2010), The Global Competitiveness Report 2010–2011 (PDF), World Economic Forum, retrieved 10 May 2011

- Sheth, N. (28 May 2009), "Outlook for Outsourcing Spending Brightens", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 3 October 2010

- Yep, E. (27 September 2011), "ReNew Wind Power Gets $201 Million Goldman Investment", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 27 September 2011

- "India Second Fastest Growing Auto Market After China", Business Line, 10 April 2010, retrieved 23 July 2011

- "India world's second largest textiles exporter: UN Comtrade". The Economic Times. 2 June 2014. Archived from the original on 5 June 2014. Retrieved 17 October 2021.

- "India's Economy: Not Just Rubies and Polyester Shirts", The Economist, 8 October 2011, retrieved 9 October 2011

- "Indian Car Exports Surge 36%", Express India, 13 October 2009, archived from the original on 28 April 2016, retrieved 5 April 2016

- "Measuring the cost of living worldwide", The Economist, 21 March 2017, archived from the original on 25 May 2017, retrieved 25 May 2017

- Economic Survey of India 2007: Policy Brief (PDF), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, October 2007, archived from the original (PDF) on 6 June 2011, retrieved 22 July 2011

- Report for Selected Countries and Subjects: Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Sri Lanka, Thailand, International Monetary Fund, April 2011, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Information Note to the Press (Press Release No.29 /2011) (PDF), Telecom Regulatory Authority of India, 6 April 2011, archived from the original (PDF) on 16 May 2011, retrieved 23 July 2011

- India: Undernourished Children – A Call for Reform and Action, World Bank, archived from the original on 7 May 2012, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Trade to Expand by 9.5% in 2010 After a Dismal 2009, WTO Reports, World Trade Organization, 26 March 2010, retrieved 23 July 2011

- Indian IT-BPO Industry, NASSCOM, 2011–2012, archived from the original on 9 May 2012, retrieved 22 June 2012

- Understanding the WTO: The Organization Members and Observers, World Trade Organization, 1995, archived from the original on 29 December 2009, retrieved 23 June 2012

- World Economic Outlook Update, International Monetary Fund, June 2011, retrieved 22 July 2011

Demographics

- Chandramouli, C. (15 July 2011), Rural Urban Distribution of Population (PDF), Ministry of Home Affairs (India), retrieved 24 January 2015

- Dev, S. M.; Rao, N. C. (2009), India: Perspectives on Equitable Development, Academic Foundation, ISBN 978-81-7188-685-2

- Dharwadker, A. (2010), "Representing India's Pasts: Time, Culture, and Problems of Performance Historiography", in Canning, C. M.; Postlewait, T. (eds.), Representing the Past: Essays in Performance Historiography, University of Iowa Press, ISBN 978-1-58729-905-6, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Drèze, J.; Goyal, A. (2009), "The Future of Mid-Day Meals", in Baru, R. V. (ed.), School Health Services in India: The Social and Economic Contexts, SAGE Publications, ISBN 978-81-7829-873-3

- Dyson, T.; Visaria, P. (2005), "Migration and Urbanisation: Retrospect and Prospects", in Dyson, T.; Casses, R.; Visaria, L. (eds.), Twenty-First Century India: Population, Economy, Human Development, and the Environment, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-928382-8

- Dyson, Tim (2018), A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8

- Fisher, Michael H. (2018), An Environmental History of India: From Earliest Times to the Twenty-First Century, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/9781316276044, ISBN 978-1-107-11162-2, LCCN 2018021693, S2CID 134229667

- Garg, S. C. (19 April 2005), Mobilizing Urban Infrastructure Finance in India (PDF), World Bank, archived from the original (PDF) on 24 August 2009, retrieved 27 January 2010

- Mallikarjun, B (November 2004), "Fifty Years of Language Planning for Modern Hindi – The Official Language of India", Language in India, 4 (11), ISSN 1930-2940, archived from the original on 10 January 2018, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Ottenheimer, H. J. (2008), The Anthropology of Language: An Introduction to Linguistic Anthropology, Cengage, ISBN 978-0-495-50884-7

- Ratna, U. (2007), "Interface Between Urban and Rural Development in India", in Dutt, A. K.; Thakur, B. (eds.), City, Society, and Planning, vol. 1, Concept, ISBN 978-81-8069-459-2

- Rorabacher, J. A. (2010), Hunger and Poverty in South Asia, Gyan, ISBN 978-81-212-1027-0

- Notification No. 2/8/60-O.L, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 27 April 1960, archived from the original on 1 October 2014, retrieved 13 May 2011

- "Census Data 2001", Office of the Registrar General and Census Commissioner, Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of India, 2010–2011, retrieved 22 July 2011

Art

- Blurton, T. Richard (1993), Hindu Art, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-39189-5

- Craven, Roy C (1997), Indian art: a concise history, New York City: Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-20302-6, OCLC 37895110

- Harle, James C. (1994), The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-06217-5

- Michell, George (2000), Hindu Art and Architecture, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-20337-8

- Rowland, Benjamin (1970), The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, Penguin Books

Culture

- Binmore, K. G. (2007), Playing for Real: A Text on Game Theory, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-530057-4

- Chopra, P. (2011), A Joint Enterprise: Indian Elites and the Making of British Bombay, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-7037-6

- Cullen-Dupont, K. (July 2009), Human Trafficking, Infobase Publishing, ISBN 978-0-8160-7545-4

- Cyriac, B. B. (9 August 2010), "Sawant Shoots Historic Gold at World Championships", The Times of India, retrieved 25 May 2011

- Das, S. K. (2005), A History of Indian Literature, 500–1399: From Courtly to the Popular, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-2171-0

- Datta, A. (2006), The Encyclopaedia of Indian Literature, vol. 2, Sahitya Akademi, ISBN 978-81-260-1194-0

- Dehejia, R. S. (7 November 2011), "Indian Grand Prix Vs. Encephalitis?", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 20 December 2011

- Deutsch, E. (1969), Advaita Vedānta: A Philosophical Reconstruction, University of Hawaiʻi Press, ISBN 978-0-8248-0271-4

- Dissanayake, W. K.; Gokulsing, M. (May 2004), Indian Popular Cinema: A Narrative of Cultural Change (2nd ed.), Trentham Books, ISBN 978-1-85856-329-9

- Futterman, M; Sharma, A (11 September 2009), "India Aims for Center Court", The Wall Street Journal, retrieved 29 September 2010

- Hansa Research (2012). "Growth: Literacy & Media Consumption" (PDF). Indian Readership Survey 2012 Q1 : Topline Findings. Media Research Users Council. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 April 2014. Retrieved 12 September 2012.

- Hart, G. L. (1975), Poems of Ancient Tamil: Their Milieu and Their Sanskrit Counterparts, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-02672-8

- Heehs, P., ed. (2002), Indian Religions: A Historical Reader of Spiritual Expression and Experience, New York University Press, ISBN 978-0-8147-3650-0, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Hoiberg, D.; Ramchandani, I. (2000), Students' Britannica India: Select Essays, Popular Prakashan, ISBN 978-0-85229-762-9

- Johnson, W. J., ed. (2008), The Sauptikaparvan of the Mahabharata: The Massacre at Night, Oxford World's Classics (2nd ed.), Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-282361-8

- Jones, G.; Ramdas, K. (2005), (Un)tying the Knot: Ideal and Reality in Asian Marriage, National University of Singapore Press, ISBN 978-981-05-1428-0

- Kālidāsa; Johnson, W. J. (2001), The Recognition of Śakuntalā: A Play in Seven Acts, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-283911-4

- Kaminsky, Arnold P.; Long, Roger D. (2011), India Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-0-313-37462-3, retrieved 12 September 2012

- Karanth, S. K. (2002), Yakṣagāna, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-357-1

- Kiple, K. F.; Ornelas, K. C., eds. (2000), The Cambridge World History of Food, vol. 2, Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-40215-6

- Kuiper, K., ed. (2010), The Culture of India, Britannica Educational Publishing, ISBN 978-1-61530-203-1, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Kumar, V. (2000), Vastushastra, All You Wanted to Know About Series (2nd ed.), Sterling Publishing, ISBN 978-81-207-2199-9

- Lal, A. (2004), The Oxford Companion to Indian Theatre, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-564446-3, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Lang, J.; Moleski, W. (1 December 2010), Functionalism Revisited, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4094-0701-0

- MacDonell, A. A. (2004), , Kessinger Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4179-0619-2

- Majumdar, B.; Bandyopadhyay, K. (2006), A Social History of Indian Football: Striving To Score, Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-34835-5

- Makar, E. M. (2007), An American's Guide to Doing Business in India, Adams, ISBN 978-1-59869-211-2

- Massey, R.; Massey, J (1998), The Music of India, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 978-81-7017-332-8

- Medora, N. (2003), "Mate Selection in Contemporary India: Love Marriages Versus Arranged Marriages", in Hamon, R. R.; Ingoldsby, B. B. (eds.), Mate Selection Across Cultures, SAGE Publications, pp. 209–230, ISBN 978-0-7619-2592-7

- Mehta, Nalin (2008), Television in India: Satellites, Politics and Cultural Change, Taylor & Francis US, ISBN 978-0-415-44759-1, retrieved 12 September 2012

- Narayan, Sunetra Sen (2013), "Context of Broadcasting in India", Globalization and Television: A Study of the Indian Experience, 1990–2010, Oxford University Press, pp. 55–69, doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198092360.003.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-809236-0

- Sengupta, R. (24 September 2010), "Is Boxing the New Cricket?", Mint, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Nakamura, H. (1999), Indian Buddhism: A Survey with Bibliographical Notes, Buddhist Tradition Series (12th ed.), Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-0272-8

- Rajadhyaksha, A.; Willemen, P., eds. (1999), Encyclopaedia of Indian Cinema (2nd ed.), British Film Institute, ISBN 978-0-85170-669-6

- Poems of Love and War: From the Eight Anthologies and the Ten Long Poems of Classical Tamil, translated by Ramanujan, A. K., New York: Columbia University Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0-231-05107-1

- Roberts, N. W. (2004), Building Type Basics for Places of Worship, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-471-22568-3

- Script error: No such module "Harvc".

- Schwartzberg, J. (2011), "India: Caste", Encyclopædia Britannica, retrieved 17 July 2011

- Silverman, S. (2007), Vastu: Transcendental Home Design in Harmony with Nature, Gibbs Smith, ISBN 978-1-4236-0132-6

- Tarlo, E. (1996), Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-78976-7, retrieved 24 July 2011

- Xavier, L. (12 September 2010), "Sushil Kumar Wins Gold in World Wrestling Championship", The Times of India, retrieved 5 October 2010

- Zvelebil, K. V. (1997), Companion Studies to the History of Tamil Literature, Brill Publishers, ISBN 978-90-04-09365-2

- Anand Crowned World Champion, Rediff, 29 October 2008, retrieved 29 October 2008

- "Taj Mahal", World Heritage Convention, United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organisation, retrieved 3 March 2012

- "Saina Nehwal: India's Badminton Star and "New Woman"", BBC News, 1 August 2010, retrieved 5 October 2010

- "Commonwealth Games 2010: India Dominate Shooting Medals", Commonwealth Games 2010, BBC, 7 October 2010, retrieved 3 June 2011

External links

Government

General information

- India. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- India at Curlie

- India web resources provided by GovPubs at the University of Colorado Boulder Libraries

- India from BBC News

Wikimedia Atlas of India

Wikimedia Atlas of India Geographic data related to India at OpenStreetMap

Geographic data related to India at OpenStreetMap- Key Development Forecasts for India from International Futures

Coordinates: 21°N 78°E / 21°N 78°E

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "National Symbols | National Portal of India". India.gov.in. Archived from the original on 4 February 2017. Retrieved 1 March 2017.

The National Anthem of India Jana Gana Mana, composed originally in Bengali by Rabindranath Tagore, was adopted in its Hindi version by the Constituent Assembly as the National Anthem of India on 24 January 1950.

- ↑ "National anthem of India: a brief on 'Jana Gana Mana'". News18. 14 August 2012. Archived from the original on 17 April 2019. Retrieved 7 June 2019.

- ↑ Wolpert 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 National Informatics Centre 2005.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Ministry of Home Affairs 1960.

- ↑ "Profile | National Portal of India". India.gov.in. Archived from the original on 30 August 2013. Retrieved 23 August 2013.

- ↑ "Constitutional Provisions – Official Language Related Part-17 of the Constitution of India". Department of Official Language via Government of India. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 18 April 2021.

- ↑ "50th Report of the Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities in India (July 2012 to June 2013)" (PDF). Commissioner for Linguistic Minorities, Ministry of Minority Affairs, Government of India. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 July 2016. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- ↑ Lewis, M. Paul; Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D., eds. (2014). "Ethnologue: Languages of the World : India" (17th ed.). Dallas, Texas: Ethnologue by SIL International. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ "Ethnologue : Languages of the World (Seventeenth edition) : Statistical Summaries". Ethnologue by SIL International. Archived from the original on 17 December 2014. Retrieved 17 December 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Library of Congress 2004.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedIMFWEO.IN - ↑ "Gini index (World Bank estimate) – India". World Bank.

- ↑ "Human Development Report 2021/2022" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 8 September 2022. Retrieved 8 September 2022.