Manipur Kingdom

| Manipur Kingdom Meetei Leipak | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princely State of British India (1891–1947) Dominion of India (1949) | |||||||||||

| 1445 BC–1949 AD | |||||||||||

Manipur State in the Hicky's Bengal Gazette of 1907 | |||||||||||

| Capital | Imphal | ||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||

• 1941 | 22,372 km2 (8,638 sq mi) | ||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• 1941 | 512,069 | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Foundation of the Kangleipak Kingdom | 1445 BC | ||||||||||

| 1824 | |||||||||||

• princely state of British India | 1891 | ||||||||||

• Accession to the Indian Union | 11 August 1947 | ||||||||||

• Merged into the Indian Union | 21 September 1949 AD | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Manipur Kingdom was an ancient independent kingdom at the India–Burma frontier[1][2][3] that was in subsidiary alliance with British India from 1824, and became a princely state in 1891.[4] It bordered Assam Province in the west and British Burma in the east, and in the 20th century covered an area of 22,327 square kilometres (8,621 sq mi) and contained 467 villages. The capital of the state was Imphal.

The early history of Manipur is composed of mythical narratives. The Kangla Fort, located on the banks of the Imphal River, is where the palace of King Pakhangba[5] was located. It was built in 1632 by king Khagemba, who had defeated Chinese invaders. In the fort, a number of temples that had traditional religious significance are located. Kangla means "dry land" in the old Meitei language.

Kangleipak State[edit]

The Kingdom of Kangleipak was established by Tangja Leela Pakhangba. He was succeeded by Ningthou Kangba, the inventor of the polo (Sagol Kangjei) and then Maliyapham Palcha, the inventor of the Meitei calendar. Many rulers successively ascended the throne of the antique realm.

King Loiyumba consolidated the kingdom by incorporating most of the principalities in the surrounding hills and is credited with having enacted a kind of written constitution for his state.[6] After subjugating all the villages within their valley Kangleipak kings grew in power and began a policy of expansion beyond their territory. In 1443 King Ningthoukhomba raided Akla, an area ruled by Shan people, initiating a policy of Manipuri claims to the neighbouring Kabaw Valley.[6] The zenith of the Kangleipak State was reached under the rule of King Khagemba (1597–1652). Khagemba's brother Prince Shalungba was not happy about Khagemba's rule so he fled to the Sylhet region where he allied with Bengali Muslim leaders. With a contingent of Sylheti soldiers, Shalungba then attempted to invade Manipur but the soldiers were captured and made to work as labourers in Manipur. These soldiers married local Meitei women and adapted to the Meitei language. They introduced hookah to Manipur and founded the Pangal or Manipuri Muslim community.[7]

Manipur State[edit]

In 1714 a king, named Meidingu Pamheiba, adopted Hinduism as the state religion and changed his name to Garib Niwaj. In 1724 the Sanskrit name Manipur ('the Abode of Jewels') was adopted as the name of the state. King Garib Niwaj made several incursions into Burma, but no permanent conquest. After the death of Gharib Nawaz in 1754, Manipur was occupied by the Kingdom of Burma and the Meitei king Jai Singh (Ching-Thang Khomba) sought help from the British. A treaty of alliance was negotiated in 1762 and a military force sent to assist Manipur. The force was later recalled and then the state was left to its own devices.[8] Manipur was invaded at the onset of the First Anglo-Burmese War, together with Cachar and Assam.

British protectorate[edit]

Following the Burmese invasions, in 1824 the king of Manipur Gambhir Singh (Chinglen Nongdrenkhomba) asked the British for help and the request was granted. Sepoys and artillery were sent and British officers trained a levy of Manipuri troops for the battles that ensued. After the Burmese were expelled, the Kabaw Valley down to the Ningthi River was added to the state.[8] In 1824–1826, on the conclusion of the First Anglo-Burmese War, Manipur became a British protectorate.[9]

Manipur remained relatively peaceful and prosperous until King Gambhir Singh's death in 1834. When he died his son was only one year old and his uncle Nara Singh was appointed as regent. That same year the British decided to restore the Kabaw Valley to the Kingdom of Burma, which had never been happy about the loss. A compensation was paid to Raja of Manipur in the form of an annual allowance of Rs 6,370 and a British residency was established in Imphal, the only town of the state, in 1835 to facilitate communication between the British and the rulers of Manipur.[8]

After a thwarted attempt on his life, Nara Singh took power and held the throne until his death in 1850. His brother Devendra Singh was given the title of Raja by the British, but he was unpopular. After only three months Chandrakirti Singh invaded Manipur and rose to the throne, while Devendra Singh fled to Cachar. Numerous members of the royal family tried to overthrow Chandrakirti Singh, but none of the rebellions was successful. In 1879, when British Deputy Commissioner G.H. Damant was killed by an Angami Naga party, the king of Manipur assisted the British by sending troops to neighbouring Kohima. Following this service to the crown, Chandrakirti Singh was rewarded with the Order of the Star of India.

After Maharaja Chandrakriti's death in 1886 his son Surachandra Singh succeeded him. As in previous occasions, several claimants to the throne tried to overthrow the new king. The first three attempts were defeated, but in 1890, following an attack on the palace by Tikendrajit and Kulachandra Singh, two of the king's brothers, Surachandra Singh announced his intention to abdicate and left Manipur for Cachar. Kulachandra Singh, the king's younger brother, then rose to the throne while Tikendrajit Singh, an older brother and commander of the Manipuri armed forces, held the real power behind the scenes. Meanwhile, Surachandra Singh, once safely away from Manipur appealed to the British for help to recover the throne.[8]

The 'Manipur Expedition'[edit]

The British decided to recognise Juvraj Kulachandra Singh as Raja, and to send a military expedition of 400 men to Manipur to punish Senapati Tikendrajit Singh as the main person responsible for the unrest and the dynastic disturbances. This action and the violent events that followed are known in British annals as the 'Manipur Expedition, 1891',[10] while in Manipur they are known as the 'Anglo-Manipur War of 1891'.

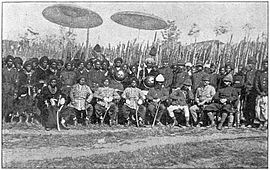

The British attempt to remove Tikendrajit from his position as military commander (Senapati) and arrest him on 24 March 1891 caused a great stir. The British Residency in Imphal was attacked and the Chief Commissioner for Assam J.W. Quinton, Col. Sken, the British Resident and other British officials were murdered. In the middle of the unrest Ethel St Clair Grimwood, the widow of Frank St Clair Grimmond, the killed British Resident, was credited with leading a retreat of surviving sepoys out of Manipur to Cachar.[11] She was later lauded as a hero.[12]) A 5,000 strong punitive expedition was sent against Manipur on 27 April 1891. Three British columns entered Manipur from British Burma, Cachar and the Naga Hills, which after several skirmishes with the 3,000 men strong Manipuri army, managed to pacify the kingdom. Following the British attack Senapati Tikendrajit and young king Kulachandra fled, but were captured. The Senapati and those Manipuris who had been involved in the killing of the British officers were tried and hanged, while the deposed King Kulachandra and other leaders of the rebellion were sent to the Cellular Jail in the Andaman Islands. At this time until 22 September 1891, Manipur was briefly annexed to British India by virtue of the doctrine of lapse. On 22 September 1891 when Meidingngu Churachand (Churachandra), a 5-year-old boy, was put on the throne, power was restored nominally to the Manipuri crown over the state. During the dynastic disturbances and the British intervention the Naga and Kuki hill tribes of the state lapsed into lawlessness, with numerous instances of murder and arson in the mountain villages, a situation that lasted well into 1894.[8]

The 20th century: Twilight and end of the princely state[edit]

The child ruler Churachand belonged to a side branch of the Manipur royal family, so that all the main contenders to the throne were bypassed. While he was a minor the affairs of state were administered by the British Political Agent, which facilitated the introduction and implementation of reforms. The first paved road to Manipur was inaugurated in 1900 —until then there had been no proper roads to reach the kingdom— and this improvement in communication facilitated a visit by Viceroy Lord Curzon in 1901. Raja Churachand was formally declared king in 1907 after completing education in Ajmer.[8] In 1918 he was given the privilege to use the title 'Maharaja' and during his reign Manipur enjoyed a period of relative peace and prosperity. In 1934 king Churachand was knighted by the British, becoming Sir Churachandra Singh.[13]

Between March 1944 and July 1944 part of Manipur and the Naga Hills District of Assam Province were occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army. The capital Imphal was shelled on 10 May 1942.

The last ruler of the Kingdom of Manipur was Maharaja Bodhchandra Singh. He ruled between 1941 and 1949.

Incorporation into India[edit]

On 15 August 1947, with the lapse of paramountcy of the British Crown, Manipur became briefly "independent", i.e., free of control from the Governor of Assam which is considered as reversion to political autonomy that exist before 1891 [14][15][16] However, the Maharaja had already agree to accede to India on 11 August, whereby he agreed to cede three subjects namely defence, external affairs and communication to India on assurance of autonomy and independence of Manipur be granted in dealing with the new India (Dominion of India).[14][17][18][19][20][21] A 'Manipur State Constitution Act 1947' was enacted, giving the state its own constitution, although this did not become known in other parts of India owing to the relative isolation of the kingdom.[16] The Government of India did not recognize the Constitution.[22]

On 21 September 1949, the Maharaja was coerced to sign a Merger Agreement with the Union of India, to take effect on 15 October the same year.[23] As a result of the agreement, the Manipur State merged into the Indian Union as a Part C State (similar to a Chief Commissioner's Province under the colonial regime, later called Union Territory), to be governed by a Chief Commissioner appointed by the Government of India. The representative assembly of Manipur was abolished. [24]

Unhappy about central rule, Rishang Keishing began a movement for representative government in Manipur in 1954. The Indian home minister, however, declared that the time was not yet ripe for the creation of representative assemblies in Part C States such as Manipur and Tripura, claiming they were located in strategic border areas of India, that the people were politically backward and that the administration in those states was still weak.[24] However, it was given a substantial measure of local self-government under the Territorial Councils Act of 1956, a legislative body and council of ministers in 1963, and full statehood in 1972.[25]

Rulers[edit]

The rulers of Manipur state were entitled to an 11-gun salute by the British authorities. The present dynasty began in 1714.[26]

- 1709–1754 Gharib Nawaz (Pamheiba) (d. 1754)

- 1754–1756 Bharat Shah (Chitsai)

- 1756–1764 Guru Sham (Gaurisiam) (d. 1764)

- 1764–1798 Jai Singh (Bhagya Chandra)

- 1798–1801 Rohinchandra (Harshachandra Singh) (d. 1801)

- 1801–1806 Maduchandra Singh (d. 1806)

- 1806–1812 Charajit Singh (d. 1812)

- 1812–1819 Marjit Singh (d. 1824)

Rajas under Burmese rule[edit]

There were two feudatory kings during the time of the Burmese invasions.

- 1819–1823 Shubol

- 1823–1825 Pitambara Singh

Rajas under British protection[edit]

- 26 Jun 1825 – 9 January 1834 Ganavira Singh (d. 1834)

- 1834–1844 Nara Singh – Regent (d. 1850)

- 1844 – 10 April 1850 Nara Singh (s.a.)

- 1850 (3 months) Devendra Singh (d. 1871)

- 1850 – May 1886 Chandrakirti Singh (s.a.) (b. 1831 – d. 1886) (from 18 February 1880, Sir Chandrakirti Singh)

- 1886 – 24 September 1890 Surachandra Singh (d. 1891)

- 24 Sep 1890 – 19 April 1891 Kulachandra Singh (b. 18.. – d. 1934)

- 19 Apr 1891 – 18 September 1891 Interregnum

- 18 Sep 1891 – 1918 Churachandra Singh (b. 1885 – d. 1941)

Maharajas[edit]

- 1918 – Sep 1941 Sir Churachandra Singh (s.a.) (from 1 January 1934, Sir Churachandra Singh)

- Sep 1941 – 15 October 1949 Bodhchandra Singh (b. 1909 – d. 1955)

British administrators[edit]

Political agents[edit]

The Political agents were subordinated to the Chief Commissioner of Assam (Lieutenant Governor of East Bengal and Assam during 1905–1912)

- 1835–1844 George Gordon[citation needed]

- 1844–1863 William McCulloch (1st time)[27]

- 1863–1865 Dillon[citation needed]

- 1865–1867 William McCulloch (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 1867–1875 Robert Brown[citation needed]

- 1875–1877 Guybon Henry Damant (acting)

- 1877–1886 Sir James Johnstone[citation needed]

- 1886 (6 weeks) Trotter (acting)

- 25 Mar 1886 – 21 April 1886 Walter Haiks (acting)

- 1886 – 24 April 1891 St. Clair Grimwood (d. 1891)

- 1891 Sir Henry Collett (British commander)

- 1891–1893 H.St.P. John Maxwell (1st time)

- 1893–1895 Alexander Porteous (1st time)

- 1895–1896 H.St.P. John Maxwell (2nd time)

- 1896–1898 Henry Walter George Cole (1st time) (acting)

- 1898–1899 Alexander Porteous (2nd time)

- 1899–1902 H.St.P. John Maxwell (3rd time)

- 1902–1904 Albert Edward Woods

- 1904–1905 H.St.P. John Maxwell (4th time)

- 1905–1908 John Shakespear (1st time)

- 1908–1909 A.W. Davis

- 1909–1914 John Shakespear (2nd time)

- 1914–1917 Henry Walter George Cole (2nd time) (s.a.)[clarification needed]

- 1917–1918 John Comyn Higgins (1st time)

- 1918–1920 William Alexander Cosgrave

- 1920–1922 L.O. Clarke (1st time)

- 1922 Christopher Gimson (1st time) (acting)

- 1922–1924 L.O. Clarke (2nd time)

- 1924–1928 John Comyn Higgins (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 12 Mar 1928 – 23 November 1928 C.G. Crawford

- 1928–1933 John Comyn Higgins (3rd time) (s.a.)

- 1933–1938 Christopher Gimson (2nd time) (s.a.)

- 1938–1941 Gerald Pakenham Stewart (1st time) (Japanese prisoner 1941–45)

- 1941–1946 Christopher Gimson (3rd time) (s.a.)

- Dec 1946 – 14 August 1947 Gerald Pakenham Stewart (2nd time)

Indian administration[edit]

Political agents[edit]

The Indian Agents were subordinated to the Governor of Assam.

Dewans[edit]

The Dewans were representing the Governor of Assam.

- 1948 – 16 April 1949 Maharaj Kumar Priyobrata Singh (s.a.)[28]

- 16 Apr 1949 – 15 October 1949 Rawal Amar Singh[29]

Flags[edit]

The State of Manipur had a set of two flags, a white one and a red one. All featured the Pakhangba dragon in the centre, although not as prominently in the latter flags.[30]

See also[edit]

- History of Manipur

- Manipur State Constitution Act 1947

- Meitei inscriptions

- Ningthouja dynasty

- Kanglei mythology

- Political integration of India

References[edit]

- ↑ Somorjit, Wangam (2016-03-01). Manipur: The Forgotten Nation of Southeast Asia. Waba Publications & Advanced Research Consortium. ISBN 978-81-926687-2-7.

- ↑ Fantz, Paul R.; Pradeep, S. V. (1995). Clitoria (Leguminosae) of South Eastern Asia.

- ↑ https://press.uchicago.edu/books/HOC/HOC_V2_B2/HOC_VOLUME2_Book2_chapter18.pdf

- ↑ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 582.

- ↑ Yuhlung, Cheithou (2013-08-28). "The Identity of Pakhangpa: The Mystical Dragon-Python God of Chothe of Manipur". Rochester, NY. SSRN 2317260.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Phanjoubam Tarapot, Bleeding Manipur, Har Anand Publications (30 July 2007) ISBN 978-8124109021

- ↑ Nath, Rajmohan (1948). The back-ground of Assamese culture. A. K. Nath. p. 90.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 "Imperial Gazetteer2 of India, Volume 17, page 186 – Imperial Gazetteer of India – Digital South Asia Library". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ Phanjoubam, Pradip (2015), The Northeast Question: Conflicts and frontiers, Routledge, pp. 3–4, ISBN 978-1-317-34004-1: "After comprehensively defeating the Burmese in 1826 in Assam and Manipur, and the signing of the Treaty of Yandabo, the British annexed Assam, but allowed Manipur to remain a protectorate state."

- ↑ Ian F.W. Beckett, Victoria's Wars, Shire, ISBN 978-0747803881, p. 62

- ↑ Reynolds, K. D. (2010). "Grimwood [née Moore; other married name Miller], Ethel Brabazon [pseud. Ethel St Clair Grimwood] (1867–1928), the heroine of Manipur". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/101006. Retrieved 2020-10-11. Template:ODNBsub

- ↑ Ethel St. Clair Grimwood, My Three Years in Manipur and Escape from the Recent Mutiny (fl.1891)

- ↑ "Indian Princely States K-Z". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "2". State, Policy and Conflicts in Northeast India. Retrieved 2021-06-21.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ↑ Akoijam, A. Bimol (28 July 2001), "How History Repeats Itself", Economic and Political Weekly, 36 (30): 2807–2812, JSTOR 4410908

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Banerjee, S. K. (January–March 1958), "Manipur State Constitution Act, 1947", The Indian Journal of Political Science, 19 (1): 35–38, JSTOR 42748891

- ↑ https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/b/b0/Instrument_of_Accession_and_Standstill_Agreement_of_Manipur_to_Dominion_of_India.pdf

- ↑ Rinku, Khumukcham (19 October 2017). "Manipur". Imphal times. Press. Retrieved 14 January 2021.

- ↑ Colonialism and Resistance: Society and State in Manipur, Taylor & Francis, 2015, p. 169, retrieved 14 January 2021

- ↑ Why Pre-Merger Political Status for Manipur: Under the Framework of the Instrument of Accession, 1947, Research and Media Cell, CIRCA, 2018, p. 26, GGKEY:8XLWSW77KUZ: "Before the controversial merger, both Manipur and India were bound by the Instrument of Accession (IOA) which the King of Manipur signed on 11 August 1947. The IOA was accepted by the Governor General of India Lord Mountbatten on 16 August 1947 vide Home Department, Government of India file no A-1/1/1947. Subsequently, the Manipur State Council approved the IOA in its meeting held on 22 August 1947 Vide Memo No. 383 PTI Reference Council Minutes Part I of 11-8-1947. The execution of the Instrument of Accession was published in the Manipur State Gazette on 27 August 1947."

- ↑ Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur 2011, p. 139; See Chapter 2 for the limitations of sovereignty under the colonial regime.

- ↑ Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur (2011), Chapter 6, p. 139.

- ↑ Haokip, Thongkholal (2012). "Political Integration of Northeast India: A Historical Analysis". Strategic Analysis. 36 (2): 304–314. doi:10.1080/09700161.2012.646508. ISSN 0970-0161. S2CID 153661583.: "The Maharajah of Manipur was invited to Shillong in September 1949 for talks on integration.... The Maharaja was placed under house arrest and debarred from any communication with the outside world. The Maharaja was thus forced to sign the ‘Merger Agreement’ with India on September 21, 1949, and Manipur became a 'Part-C state' of the Indian Union."

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Guha, Ramachandra (2008), India after Gandhi: The History of the World's Largest Democracy, Pan Macmillan, Section 13.V, ISBN 978-0330396110

- ↑ Agnihotri, Constitutional Development in North-East India (1996), p. 68.

- ↑ "MANIPUR". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur (2011), pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Singh, Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur (2011), pp. 141–142.

- ↑ "Manipur". Retrieved 1 April 2015.

Bibliography[edit]

- Agnihotri, S. K. (1996), "Constitutional Development in North-East India since 1947", in B. Datta-Ray; S. P. Agrawal (eds.), Reorganization of North-East India Since 1947, Concept Publishing Company, pp. 57–92, ISBN 978-81-7022-577-5

- Singh, Haorongbam Sudhirkumar (2011), Socio-religious and Political Movements in Modern Manipur 1934–51, Jawaharlal Nehru University/Shodhganga

- L. Joychandra Singh, The Lost Kingdom: Royal Chronicle of Manipur, Prajatantra Publishing House, 1995.

External links[edit]

- Territorial Councils Act, 1956, Lok Sabha Bills, retrieved 25 November 2020.

- Puya – Meithaba

- Seven clans of Manipur

Coordinates: 24°49′N 93°57′E / 24.817°N 93.950°E

- Governmnt of Manipur (1949). Manipur Gazette, 1949, January-June. pp. 1–5.

- Hosting sites of FOTW, National Flag

- Bharatpedia articles incorporating a citation from the ODNB

- Former country articles requiring maintenance

- Articles with unsourced statements from September 2015

- Princely states of India

- History of Manipur

- Bengal Presidency

- Kingdoms of Northeast India

- Former kingdoms

- Former country or territory templates

- History of Myanmar

- Former monarchies of Asia

- 12th-century establishments in India

- 1110 establishments in Asia

- 1949 disestablishments in India