Punjab, Pakistan

Punjab (Urdu & Punjabi: پنجاب, romanized: Panjāb) is a province of Pakistan. It has a population of about 110,000,000, according to the 2017 Pakistan Census. It is the most populous of the four provinces of Pakistan.

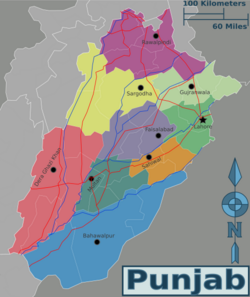

Forming the bulk of the transnational Punjab region of Pakistan and India, it is bordered by the Pakistani provinces of Sindh, Balochistan, and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, the enclave of Islamabad, and Pakistan-administered Azad Kashmir. It also shares borders with the Indian territories of Punjab, Rajasthan, and Jammu and Kashmir. The capital is Lahore, a cultural, historical, economic and cosmopolitan centre of Pakistan where the country's cinema industry, and much of its fashion industry, are based.[5][6] Other major cities include Gujranwala, Faisalabad, Multan, Rawalpindi, and Sialkot. Punjab is also the world's fifth-most populous subnational entity, and the most populous outside China or India.

Punjab has been inhabited since ancient times. The Indus Valley Civilization, dating to 2600 BCE, was first discovered at Harappa.[7] Punjab features heavily in the Sanskrit epic, the Mahabharata, and is home to Taxila, site of what is considered by many to be the oldest university in the world.[8][9][10][11][12] In 326 BCE, Alexander the Great defeated King Porus at the Battle of the Hydaspes near Mong, Punjab. Subsequently, it formed part of the Mauryan, Kushan and Gupta empires. The Umayyad empire conquered Punjab in the 8th century CE. In the subsequent centuries, Punjab was invaded and conquered by the Hindu Shahis, Ghaznavids, Ghurids, Delhi Sultanate, Mughals, Durranis and the Sikhs. Punjab reached the height of its splendour during the reign of the Mughal Empire, which for a time ruled from Lahore. During the 18th century, Nader Shah's invasion of the Mughal Empire caused Mughal authority in the Punjab to fall apart and it thus fell into chaos. The Durrani Afghans under Ahmad Shah Durrani wrested control of Punjab but lost it to the Sikhs after a successful rebellion which allowed Sikh armies to claim Lahore in 1759. The Sikh Empire was established in 1799 under the rule of Ranjit Singh with his capital based in Lahore, until its defeat by the British. Punjab was central to the independence movements of both India and Pakistan, with Lahore being the site of both the Declaration of Indian Independence, and the resolution calling for the establishment of Pakistan. The province was formed when the Punjab province of British India was divided along religious boundaries in 1947 by the Radcliffe Line after Partition.[13]

Punjab is Pakistan's most industrialised province, with the industrial sector making up 24% of the province's gross domestic product.[14] Punjab is known in Pakistan for its relative prosperity,[15] and has the lowest rate of poverty amongst all Pakistani provinces.[16][17] A clear divide is present between the northern and southern portions of the province;[15] with poverty rates in prosperous northern Punjab amongst the lowest in Pakistan,[18] while some in south Punjab are amongst the most impoverished.[19] Punjab is also one of South Asia's most urbanised regions with approximately 40% of people living in urban areas.[20] Its human development index rankings are high relative to the rest of Pakistan.

The province has been strongly influenced by Sufism, with numerous Sufi shrines spread across Punjab, which attract millions of devotees annually.[21] The founder of the Sikh faith, Guru Nanak, was born in the Punjab town of Nankana Sahib near Lahore.[22][23][24] Punjab is also the site of the Katasraj Temple, which features prominently in Hindu mythology.[25] Several UNESCO World Heritage Sites are located in Punjab, including the Shalimar Gardens, the Lahore Fort, the archaeological excavations at Taxila, and the Rohtas Fort.[26]

Etymology[edit]

History[edit]

Ancient history[edit]

The oldest evidence of human life in Pakistan has been found in Soan River valley, discovered during the excavations of prehistoric mounds.[27] Tools up to two million years old have been recovered in the Potohar plateau. In the Soan River, many fossil bearing rocks are exposed on the surface.

Punjab was part of the Indus Valley Civilization, more than 5000 years old.[28][29] The main site in Punjab was the city of Harrapa. The Indus Valley Civilization spanned much of what is today Pakistan and eventually evolved into the Indo-Aryan civilization.[30] The arrival of the Indo-Aryans led to the flourishing of the Vedic civilization along the length of the Indus River. Punjab during the Mahabharata times was known as Panchanada.[31][32] This civilization shaped subsequent cultures in South Asia. The Vedic civilization also flourished in the ancient city of Taxila in Gandhara.[33]

According to historians, this region was ruled by many small kingdoms and tribes around 4th and 5th BCE. The earliest known notable local king of this region was known as King Porus, who fought the famous Battle of the Hydaspes against Alexander the Great in 326 BCE near the river Jhelum.[34] His kingdom, known as Pauravas, was situated between the river Hydaspes (modern Jhelum) and Acesines (modern day Chenab).

Punjab was also part of other empires including the Achaemenids, Macedonians, Mauryans, the Indo-Scythians, Guptas, Kushans, and Hindu Shahis.[35]

Due to its location, the Punjab region came under constant attack and influence from the west and witnessed centuries of foreign invasions by the Greeks, Kushans, Scythians, Turks, Arabs and Mughals.

The city of Taxila, founded around 1000 BCE,[36] was reputed to house one of the earliest universities in the world, the Takshashila University.[37] One of its instructors was the Vedic statesman and philosopher Chanakya. Taxila was a major centre of political control, intellectual discourse and trade between the Hellenistic kingdoms and the Maurya Empire. Taxila is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, valued for its archaeological and religious history.

Gandhara civilisation (750 BC to 518 BC)[edit]

Gandhāra was an ancient kingdom situated in the northwestern region of Pakistan, in the Peshawar valley and Potohar plateau with its capital at Taxila in modern northwestern Pakistan. Gandhara's existence is attested since the time of the Rigveda (c. 1500 – c. 1200 BCE),[38][39] as well as the Zoroastrian Avesta, which mentions it as Vaēkərəta, the sixth most beautiful place on earth created by Ahura Mazda. Gandhara was conquered by the Persian Achaemenid Empire in the 6th century BCE, Alexander the Great in 327 BCE, and later became part of the Maurya Empire before being a centre of the Indo-Greek Kingdom. The region was a major centre for Greco-Buddhism under the Indo-Greeks and Gandharan Buddhism under later dynasties. Gandhara also a central location for the spread of Buddhism to Central Asia and East Asia.[40] The primary cities of Gandhara were Puruṣapura (Peshawar), Takṣaśilā (Taxila), and Pushkalavati (Charsadda). Gandhara's language was a Prakrit or "Middle Indo-Aryan" dialect, usually called Gāndhārī. The language used the Kharosthi script, which died out about the 4th century.

Achaemenid Persian and Macedonian Greek Empires[edit]

The Achaemenid Persian empire included Gandhara and western Punjab, administered through the satrapies of Gandāra, Hindush and Sattagydia.

Having conquered Drangiana, Arachosia, Gedrosia and Seistan in ten days, Alexander the Great (known in Urdu as 'Sikander-e-Azam') crossed the Hindu Kush and was thus fully informed of the magnificence of the country and its riches in gold, gems and pearls. However, Alexander had to encounter and reduce the tribes on the border of Punjab before entering the luxuriant plains. Having taken a northeasterly direction, he marched against the Aspii (mountaineers), who offered vigorous resistance, but were subdued.[citation needed] Alexander then marched through Ghazni, blockaded Magassa, and then marched to Ora and Bazira. Turning to the northeast, Alexander marched to Pucela, the capital of the district now known as Pakhli. He entered Western Punjab, where the ancient city of Nysa (at the site of modern-day Mong) was situated. A coalition was formed against Alexander by the Cathians, the people of Multan, who were very skilful in war. Alexander invested many troops, eventually killing 17,000 Cathians in this battle, and the city of Sagala (present-day Sialkot) was razed to the ground. The Battle of the Hydaspes was fought astride the Jhelum River in western Punjab against the regional chieftain Porus, and the Siege of the Malli Tribe which occurred at the confluence of the Indus and Hydaspes Rivers near modern Multan (during which Alexander suffered a near-fatal arrow wound). Alexander left Punjab in 326 B.C. and continued to campaign down the course of the Indus River in modern-day Sindh and Baluchistan.[citation needed]

Indo-Greek Kingdom (180 BC to 10 AD)[edit]

The Indo-Greek Kingdom or Graeco-Indian Kingdom was a Hellenistic kingdom covering most of the Punjab. The Indo-Greek kingdom founded by Demetrius (180-165 BC) included Gandhara and Punjab and reached its greatest extent under Menander (165-150 BC), with its capital in Sagala (present-day Sialkot), thriving the greco-buddhist culture in the region.[41][42] Agriculture flourished and trading cities (such as Multan and Lahore) grew in wealth.

Indo-Scythian Kingdom (150 BC to 400 AD)[edit]

The Indo-Scythian king Maues invaded Indo-Greek territories in Punjab and established an Indo-Scythian empire. Maues first conquered Gandhara and Taxila around 80 BCE, but his kingdom disintegrated after his death. The Indo-Scythians ultimately established a kingdom in the northwest south Asia, based near Taxila, with two great Satraps, one in Mathura in the east, and one in Surastrene (Gujarat) in the southwest. The Indo-Scythians seem to have been followers of Buddhism, and many of their practices apparently continued those of the Indo-Greeks.[citation needed]

Indo-Parthian Kingdom (19 AD to 226 AD)[edit]

The Indo-Parthian Kingdom was ruled by the Gondopharid dynasty with its capital at Taxila, Punjab. Gondophares, founder of the Indo-Parthian kingdom, was a ruler of Seistan in what is today eastern Iran, probably a vassal or relative of the Apracarajas. Around 20–10 BCE, he made conquests in the former Indo-Scythian kingdom, perhaps after the death of the important ruler Azes. Gondophares became the ruler of areas comprising Arachosia, Seistan, Sindh, Punjab, and the Kabul valley. The temple of Jandial, Taxila is usually interpreted as a Zoroastrian fire temple from the period of the Indo-Parthians.[citation needed]

Kushan Empire (30 AD to 375 AD)[edit]

The Kushan Empire was a syncretic empire, formed by the Yuezhi, in the Bactrian territories in the early 1st century. Around 75 CE under the leadership of Kujula Kadphises they gained control of Gandhara and other parts of what is now Pakistan. The Kushan period is considered the Golden Period of Gandhara. Gandhara's culture peaked during the reign of the Kushan ruler Kanishka the Great (128–151). The cities of Taxila (Takṣaśilā) at Sirsukh and Peshawar were built. Kanishka was a great patron of the Buddhist faith; Buddhism spread to Central Asia and the Far East across Bactria and Sogdia, where his empire met the Han Empire of China.

Hephthalite Empire[edit]

The Hephthalite Huns captured Gandhara around 451, and did not adopt Buddhism, but in fact "perpetrated frightful massacres." Mihirakula became a "terrible persecutor" of the Buddhist religion.[43] During their rule, Hinduism revived itself and the Buddhist civilisation in Gandhara declined.

Arrival of Islam[edit]

Before the arrival of Islam, the Punjab region was home to a diverse plethora of faiths, mainly Hinduism, Buddhism or Greco-Buddhism.[41]

The Arab Umayyad army brought Islam to the region led by Muhammad bin Qasim who conquered Sindh and Southern Punjab in 712, by defeating Raja Dahir. The Umayyad Caliphate was the second Islamic caliphate established after the death of Muhammad. It was ruled by the Umayyad dynasty, whose name derives from Umayya ibn Abd Shams, the great-grandfather of the first Umayyad caliph.

Islam was introduced into Northern Punjab during the reign of Mahmud of Ghazni in the 11th century and the region subsequently became part of various Turko-Persian and Turko-Mongol Muslim empires.

The Ghaznavids, a Persianate Muslim dynasty of Turkic mamluk origin,[44][lower-alpha 1][45] had earlier conquered and converted many Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms of Afghanistan. The province of Punjab was made part of the Ghaznavid Empire with Lahore as its second capital. The region became predominantly Muslim due to missionary Sufi saints whose dargahs dot the landscape of the Punjab region. The famous Sufi mystic Ali Hujwiri arrived from Ghazni and settled in Lahore during the reign of Ghaznavids in 11th century.

Over the next millennium Islam flourished in Punjab as it became part of different Muslim empires including the Ghurids, Delhi Sultanate and Mughals. In cooperation with local Punjabi tribes and others, a millennium long Islamic dominance was achieved across South Asia and with its peak during the Mughal Empire.

Mughal Empire[edit]

The Punjab region rose to significance in the Mughal Empire when Lahore became the capital for the royal family in 1585,[46] the legacy of which is seen today in its rich display of Mughal architecture all over modern day Punjab, Pakistan.

The Mughals left an indelible mark on the landscape of Punjab from 1556 to 1739 by commissioning the construction of great gardens, forts, tombs, baths and mosques such as the Shalimar Gardens,[47] Lahore Fort, Tomb of Jahangir, Tomb of Nur Jahan, Shahi Hammam, Akbari Sarai, Wazir Khan Mosque, and the Badshahi Mosque, all situated in Lahore, as well as Hiran Minar and others elsewhere in Punjab. Akbar established two of his original twelve subahs (imperial top-level provinces) in Punjab:

- (northern) Lahore Subah, bordering Kabul (Afghanistan), (later) split-off Kashmir, (Old) Delhi and Multan subahs

- (southern) Multan Subah, bordering Kabul, Lahore, (Old) Delhi, Ajmer, Thatta (Sindh) subahs, the Persian Safavid empire[citation needed] and shortly Qandahar subah.

Later Mughals[edit]

After the death of the last great Mughal emperor Aurangzeb, in 1707, Mughal authority significantly weakened but didn't totally vanish despite Nadir Shah's invasion in 1739. The centralised authority that had existed during Aurangzeb's rule and the rule of his predecessors was now largely in the hands of governors and Nawabs (semi autonomous rulers) who gave their nominal allegiance to the Mughal emperor at Delhi.

This would change, however, in 1752, when Nader Shah's general Ahmad Shah Durrani who founded the Durrani Empire, defeated Mir Mannu, the last Mughal governor of Punjab. The Mughal emperor ceded control of the subahs that constituted Punjab namely the Lahore and Multan subahs over to Ahmad Shah Durrani.

Durranis and Marathas[edit]

In 1758 Raghunath Rao, a general of the Hindu Maratha Empire, conquered Lahore and Attock. Timur Shah Durrani, the son and viceroy of Ahmad Shah Durrani, was driven out of Punjab. Lahore, Multan and Kashmir provinces were under Maratha rule for the most part.[48] In Punjab and Kashmir, the Marathas were now major players.[49][50]

The Third Battle of Panipat took place in 1761, Ahmad Shah Abdali defeated the Marathas and reversed their gains in the regions of Punjab and Kashmir by re-consolidating control over them. Battles with Powerful Maratha empire weakened the Afghan dominance over the region and created a partial power vacuum in the region[51]

Sikh Empire[edit]

In the mid-fifteenth century, the religion of Sikhism was born. During the Mughal empire, many Hindus increasingly adopted Sikhism. The Sikhs became a formidable military force after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707 and challenged the Mughals and later the Durrani Afghans for power in Punjab. After fighting Ahmad Shah Durrani in the later eighteenth century, the Sikh Misls took control of Punjab and its capital Lahore was captured by the Bhangi Misl. In 1799 Ranjit Singh, ruler of the Sukerchakia Misl, defeated the Bhangi Misl and captured Lahore thereby proclaiming himself as the "Maharaja of Punjab" at the age of 21. Ranjit Singh made Lahore his capital and formed a sophisticated Sikh Empire which lasted from 1799 to 1849. Ranjit Singh modernized his Sikh Khalsa army by using Franco-British principles and by employing veterans of the Napoleonic Wars to train the infantry in European style. Ranjit Singh expanded his empire so that by his death in 1839 his empire included most of Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Kashmir.

Ranjit Singh was not without opponents who challenged his authority in the regions he had conquered. He faced huge opposition from Nawab Muzaffar Khan, Azim Khan, Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Mir Painda Khan. In 1818 Nawab Muzaffar Khan was killed by the Sikhs at the Battle of Multan after putting up stout resistance for many years. Azim Khan was the governor of Kashmir from 1812 until 1819 when Ranjit Singh captured it for himself. In 1823 Azim Khan took control of Peshawar and with support from Pashtun tribesmen faced off against the encroaching Khalsa army in the Battle of Nowshera. He abandoned his troops whilst they regrouped to continue fighting until they were defeated. Azim Khan retreated to Kabul where he died shortly thereafter due to grief. Syed Ahmad Barelvi was an Indian Muslim who declared Jihad against the Sikhs by garnering support from local Pashtun tribesmen and attempted to create an Islamic state with strict enforcement of Sharia.[52] In 1821 Syed Ahmad Barelvi spent two years organizing popular and material support for his Punjab campaign. In December 1826 Sayyid Ahmad Barelvi and his followers clashed with Sikh troops at Akora Khattak, with no decisive result. Barelvi's movement weakened after there was infighting with his Pashtun followers and in a major battle near the town of Balakot in 1831, Syed Ahmad Barelvi and Shah Ismail Shaheed with volunteer Muslims were defeated and killed by the Sikh Army.[53] Only Mir Painda Khan was able to maintain his independence at Tanawal in Hazara from the Sikh Empire. From about 1813 he began a series of rebellions against the Sikhs which continued throughout his lifetime inflicting defeats on the Sikhs[citation needed] whilst also losing territory to them before being poisoned in 1844. James Abbott, British officer and deputy commissioner at Hazara in 1851, described Mir Painda Khan as "a chief renowned on the border, a wild and energetic man who was never subjugated by the Sikhs".[54]

British Empire[edit]

Maharaja Ranjit Singh's death in the summer of 1839 brought political chaos and the subsequent battles of succession and the bloody infighting between the factions at court weakened the state. Relationships with neighbouring British territories then broke down, starting the First Anglo-Sikh War; this led to a British official being resident in Lahore and the annexation in 1849 of territory south of the Satluj to British India. After the Second Anglo-Sikh War in 1849, the Sikh Empire became the last territory to be merged into British India. In Jhelum 35 British soldiers of the HM XXIV regiment were killed by the local resistance during the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[55]

Pakistani Independence[edit]

In 1947 the Punjab province of British India was divided along religious lines into West Punjab and East Punjab. Western Punjab was assimilated into the new country of Pakistan, while East Punjab became a part of modern-day India. This led to massive rioting as both sides committed atrocities against fleeing refugees.

The part of the Punjab now in Pakistan once formed a major region of British Punjab, and was home to a large minority population of Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs up to 1947 apart from the Muslim majority.[56]

Migration between Eastern and Western Punjab was continuous before independence. By the 1900s Western Punjab was predominantly Muslim and supported the Muslim League and Pakistan Movement. After independence, the minority Hindus and Sikhs fled massacres and violence and migrated to India while Muslim refugees from India settled in the Western Punjab and across Pakistan, having fled pogroms that almost entirely depopulated Eastern Punjab of its Muslim population,[57] while Western Punjab was left with virtually no Hindus and Sikhs.

Recent history[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (February 2019) |

Since the 1950s, Punjab industrialised rapidly. New factories were established in Lahore, Sargodha, Multan, Gujrat, Gujranwala, Sialkot, Wah and Rawalpindi.

Agriculture continues to be the largest sector of Punjab's economy. The province is the breadbasket of the country as well as home to the largest ethnic group in Pakistan, the Punjabis. Unlike neighbouring India, there was no large-scale redistribution of agricultural land. As a result, most rural areas are dominated by a small set of feudalistic land-owning families.

In the 1950s there was tension between the eastern and western halves of Pakistan. To address the situation, a new formula resulted in the abolition of the province status for Punjab in 1955. It was merged into a single province West Pakistan. In 1972, after East Pakistan seceded and became Bangladesh, Punjab again became a province.

Punjab witnessed major battles between the armies of India and Pakistan in the wars of 1965 and 1971. Since the 1990s Punjab hosted several key sites of Pakistan's nuclear program such as Kahuta. It also hosts major military bases such as at Sargodha and Rawalpindi. The peace process between India and Pakistan, which began in earnest in 2004, has helped pacify the situation. Trade and people-to-people contacts through the Wagah border are now starting to become common. Indian Sikh pilgrims visit holy sites such as Nankana Sahib.

Geography[edit]

Punjab is Pakistan's second largest province by area after Balochistan with an area of 205,344 square kilometres (79,284 square miles).[58] It occupies 25.8% of the total landmass of Pakistan.[58] Punjab province is bordered by Sindh to the south, the province of Balochistan to the southwest, the province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa to the west, and the Islamabad Capital Territory and Azad Kashmir in the north. Punjab borders Jammu and Kashmir in the north, and the Indian states of Punjab and Rajasthan to the east.

The capital and largest city is Lahore which was the historical capital of the wider Punjab region. Other important cities include Faisalabad, Rawalpindi, Gujranwala, Sargodha, Multan, Sialkot, Bahawalpur, Gujrat, Sheikhupura, Jhelum and Sahiwal. The undivided Punjab region was home to six rivers, of which five flow through Pakistan's Punjab province. From west to east, the rivers are: the Indus, Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi and Sutlej. It is the nation's only province that touches every other province; it also surrounds the federal enclave of the national capital city at Islamabad. In the acronym P-A-K-I-S-T-A-N, the P is for Punjab.[59][60]

Topography[edit]

Punjab's landscape consists mostly consists of fertile alluvial plains of the Indus River and its four major tributaries in Pakistan, the Jhelum, Chenab, Ravi, and Sutlej rivers which traverse Punjab north to south – the fifth of the "five waters" of Punjab, the Beas River, lies exclusively in the Indian state of Punjab. The landscape is amongst the most heavily irrigated on earth and canals can be found throughout the province. Punjab also includes several mountainous regions, including the Sulaiman Mountains in the southwest part of the province, the Margalla Hills in the north near Islamabad, and the Salt Range which divides the most northerly portion of Punjab, the Pothohar Plateau, from the rest of the province. Sparse deserts can be found in southern Punjab near the border with Rajasthan and near the Sulaiman Range. Punjab also contains part of the Thal and Cholistan deserts. In the South, Punjab's elevation reaches 2,327 metres (7,635 ft)[citation needed] near the hill station of Fort Munro in Dera Ghazi Khan.

Climate[edit]

Most areas in Punjab experience extreme weather with foggy winters, often accompanied by rain. By mid-February the temperature begins to rise; springtime weather continues until mid-April, when the summer heat sets in.

The onset of the southwest monsoon is anticipated to reach Punjab by May, but since the early 1970s, the weather pattern has been irregular. The spring monsoon has either skipped over the area or has caused it to rain so hard that floods have resulted. June and July are oppressively hot. Although official estimates rarely place the temperature above 46 °C, newspaper sources claim that it reaches 51 °C and regularly carry reports about people who have succumbed to the heat. Heat records were broken in Multan in June 1993, when the mercury was reported to have risen to 54 °C. In August the oppressive heat is punctuated by the rainy season, referred to as barsat, which brings relief in its wake. The hardest part of the summer is then over, but cooler weather does not come until late October.

Recently the province experienced one of the coldest winters in the last 70 years.[61]

Punjab's region temperature ranges from −2° to 45 °C, but can reach 50 °C (122 °F) in summer and can touch down to −10 °C in winter.

Climatically, Punjab has three major seasons:[62]

- Hot weather (April to June) when temperature rises as high as 123 °F (51 °C).

- Rainy season (July to September). Average rainfall annual ranges between 96 cm sub-mountain region and 46 cm in the plains.

- Cold / Foggy / mild weather (October to March). Temperature goes down as low as 35.6 °F (2.0 °C).

Weather extremes are notable from the hot and barren south to the cool hills of the north. The foothills of the Himalayas are found in the extreme north as well, and feature a much cooler and wetter climate, with snowfall common at higher altitudes.

Population and society[edit]

Demographics[edit]

| Historical population figures[63] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Population | Urban | Rural |

|

| |||

| 1951 | 20,540,762 | 3,568,076 | 16,972,686 |

| 1961 | 25,463,974 | 5,475,922 | 19,988,052 |

| 1972 | 37,607,423 | 9,182,695 | 28,424,728 |

| 1981 | 47,292,441 | 13,051,646 | 34,240,795 |

| 1998 | 73,621,290 | 23,019,025 | 50,602,265 |

| 2017 | 110,012,615 | 70,008,451 | 40,401,164 |

The province is home to over half the population of Pakistan, and is the world's fifth-most populous subnational entity, and the most populous outside China or India. Punjabis are a heterogeneous group comprising different tribes, clans (Urdu: برادری) or communities. In Pakistani Punjab, non-tribal social distinctions are primarily based on traditional occupations such as blacksmiths or artisans, as opposed to rigid social stratifications.[64]

Punjab has the lowest poverty rates in Pakistan, although a divide is present between the northern and southern parts of the province.[15] Sialkot District in the prosperous northern part of the province has a poverty rate of 5.63%,[65] while Rajanpur District in the poorer south has a poverty rate of 60.05%.[19]

Languages[edit]

The major native language spoken in the Punjab is Punjabi, representing the largest ethnic group in the country. Punjabi is recognized as the provincial language of Punjab but is not given any official recognition in the Constitution of Pakistan at the national level.

Saraiki is mostly spoken in south Punjab,[67] and Pashto, spoken in some parts of north west Punjab, especially in Attock District and Mianwali District near Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province.

The use of Urdu and English as the near exclusive languages of broadcasting, the public sector, and formal education have led some to fear that Punjabi in Pakistan is being relegated to a low-status language and that it is being denied an environment where it can flourish. Several prominent educational leaders, researchers, and social commentators have echoed the opinion that the intentional promotion of Urdu and the continued denial of any official sanction or recognition of the Punjabi language amounts to a process of "Urdu-isation" that is detrimental to the health of the Punjabi language[68][69][70] In August 2015, the Pakistan Academy of Letters, International Writer's Council (IWC) and World Punjabi Congress (WPC) organised the Khawaja Farid Conference and demanded that a Punjabi-language university should be established in Lahore and that Punjabi language should be declared as the medium of instruction at the primary level.[71][72] In September 2015, a case was filed in Supreme Court of Pakistan against Government of Punjab, Pakistan as it did not take any step to implement the Punjabi language in the province.[73][74] Additionally, several thousand Punjabis gather in Lahore every year on International Mother Language Day.

Hafiz Saeed, chief of Jama'at-ud-Da'wah (JuD) has questioned Pakistan's decision to adopt Urdu as its national language in a country where majority of people speak Punjabi language, citing his interpretation of Islamic doctrine as encouraging education in the mother-tongue.[75] The list of thinktanks, political organisations, cultural projects, and individuals that demand authorities at the national and provincial level to promote the use of the language in the public and official spheres includes:

- Cultural and research institutes: Punjabi Adabi Board, the Khoj Garh Research Centre, Punjabi Prachar, Institute for Peace and Secular Studies, Adbi Sangat, Khaaksaar Tehreek, Saanjh, Maan Boli Research Centre, Punjabi Sangat Pakistan, Punjabi Markaz, Sver International

- Trade unions and youth groups: Punjabi Writers Forum, National Students Federation, Punjabi Union-Pakistan, Punjabi National Conference, National Youth Forum, Punjabi Writers Forum, National Students Federation, Punjabi Union, Pakistan, and the Punjabi National Conference.

- Notable activists include Tariq Jatala, Farhad Iqbal, Diep Saeeda, Khalil Ojla, Afzal Sahir, Jamil Ahmad Paul, Mazhar Tirmazi, Mushtaq Sufi, Biya Je, Tohid Ahmad Chattha and Bilal Shaker Kahaloon, Nazeer Kahut[76][77][78]

Religions[edit]

The Punjabi people first practiced Hinduism, the oldest recorded religion in the Punjab region.[79] An ancient Indian law book called the Manusmriti, developed by Brahmin Hindu priests, shaped Punjabi religious life from 200 BC onward.[79] The spread of Buddhism and Jainism in India saw many Hindu Punjabis adopting the Buddhist and Jain faith though the decline of Buddhism in the Indian subcontinent resulted in Punjab becoming a Hindu society again, though Jainism continued as a minority religion.[80][81] The arrival of Islam in medieval India resulted in the conversion of some Hindu Punjabis to Islam,[82][79] and the rise of Sikhism in the 1700s saw some Punjabis, both Hindu and Muslim, accepting the new Sikh faith.[79][83] A number of Punjabis during the colonial period of India became Christians, with all of these religions characterizing the religious diversity now found in the Punjab region.[79]

Religion in Punjab, Pakistan (2017 Census)[84][85]

The population of Punjab (Pakistan) is estimated to be 110,012,442, of which as per as 2017 census, 107,559,164 i.e. (97.2%) Muslim with a Sunni Hanafi majority and a Shia Ithna 'ashariyah minority. The largest non-Muslim minority is Christians and make up 2,068,233 i.e. (2.5%) of the population. Hindus form about 220,024 I.e (0.2%) of the population. The other minorities include Sikhs, Parsis and Baháʼís.[85]

Provincial government[edit]

The Government of Punjab is a provincial government in the federal structure of Pakistan, is based in Lahore, the capital of the Punjab Province. The Chief Minister of Punjab (CM) is elected by the Provincial Assembly of the Punjab to serve as the head of the provincial government in Punjab, Pakistan. The current Chief Minister is Sardar Usman Buzdar He got elected as a result of 25 July 2018 elections. The Provincial Assembly of the Punjab is a unicameral legislature of elected representatives of the province of Punjab, which is located in Lahore in eastern Pakistan. The Assembly was established under Article 106 of the Constitution of Pakistan as having a total of 371 seats, with 66 seats reserved for women and eight reserved for non-Muslims.

There are 48 departments in Punjab government. Each Department is headed by a Provincial Minister (Politician) and a Provincial Secretary (A civil servant of usually BPS-20 or BPS-21). All Ministers report to the Chief Minister, who is the Chief Executive. All Secretaries report to the Chief Secretary of Punjab, who is usually a BPS-22 Civil Servant. The Chief Secretary in turn, reports to the Chief Minister. In addition to these departments, there are several Autonomous Bodies and Attached Departments that report directly to either the Secretaries or the Chief Secretary.

Divisions[edit]

| Sr. No. | Division | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 45,588 | 11,464,031 |

| 2 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 38,778 | 11,014,398 |

| 3 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 17,917 | 14,177,081 |

| 4 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 17,206 | 16,123,984 |

| 5 | Lahore | Lahore | 16,104 | 19,398,081 |

| 6 | Multan | Multan | 21,137 | 12,265,161 |

| 7 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 22,255 | 10,007,821 |

| 8 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 10,302 | 7,380,386 |

| 9 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 26,360 | 8,181,499 |

When the divisions were restored as a tier of government in 2008, a tenth division – Sheikhupura Division – was created from part of Lahore Division.

Districts[edit]

| Sr. No. | District | Headquarters | Area (km2) |

Population (2017) |

Density (people/km2) |

Division |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Attock | Attock | 6,858 | 1,883,556 | 274 | Rawalpindi |

| 2 | Bahawalnagar | Bahawalnagar | 8,878 | 2,981,919 | 335 | Bahawalpur |

| 3 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 24,830 | 3,668,106 | 147 | Bahawalpur |

| 4 | Bhakkar | Bhakkar | 8,153 | 1,650,518 | 202 | Sargodha |

| 5 | Chakwal | Chakwal | 6,524 | 1,495,982 | 229 | Rawalpindi |

| 6 | Chiniot | Chiniot | 2,643 | 1,369,740 | 518 | Faisalabad |

| 7 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 11,922 | 2,872,201 | 240 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 8 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 5,856 | 7,873,910 | 1344 | Faisalabad |

| 9 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 3,622 | 5,014,196 | 1384 | Gujranwala |

| 10 | Gujrat | Gujrat | 3,192 | 2,756,110 | 863 | Gujranwala |

| 11 | Hafizabad | Hafizabad | 2,367 | 1,156,957 | 488 | Gujranwala |

| 12 | Jhang | Jhang | 8,809 | 2,743,416 | 311 | Faisalabad |

| 13 | Jhelum | Jhelum | 3,587 | 1,222,650 | 340 | Rawalpindi |

| 14 | Kasur | Kasur | 4,796 | 3,454,996 | 720 | Lahore |

| 15 | Khanewal | Khanewal | 4,349 | 2,921,986 | 671 | Multan |

| 16 | Khushab | Khushab | 6,511 | 1,281,299 | 196 | Sargodha |

| 17 | Lahore | Lahore | 1,772 | 11,126,285 | 6278 | Lahore |

| 18 | Layyah | Layyah | 6,291 | 1,824,230 | 290 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 19 | Lodhran | Lodhran | 2,778 | 1,700,620 | 612 | Multan |

| 20 | Mandi Bahauddin | Mandi Bahauddin | 2,673 | 1,593,292 | 596 | Gujranwala |

| 21 | Mianwali | Mianwali | 5,840 | 1,546,094 | 264 | Sargodha |

| 22 | Multan | Multan | 3,720 | 4,745,109 | 1275 | Multan |

| 23 | Muzaffargarh | Muzaffargarh | 8,249 | 4,322,009 | 523 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 24 | Narowal | Narowal | 2,337 | 1,709,757 | 731 | Gujranwala |

| 25 | Nankana Sahib[86] | Nankana Sahib | 2,960 | 1,356,374 | 458 | Lahore |

| 26 | Okara | Okara | 4,377 | 3,039,139 | 694 | Sahiwal |

| 27 | Pakpattan | Pakpattan | 2,724 | 1,823,687 | 669 | Sahiwal |

| 28 | Rahim Yar Khan | Rahim Yar Khan | 11,880 | 4,814,006 | 405 | Bahawalpur |

| 29 | Rajanpur | Rajanpur | 12,319 | 1,995,958 | 162 | Dera Ghazi Khan |

| 30 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 5,286 | 5,405,633 | 1322 | Rawalpindi |

| 31 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 3,201 | 2,517,560 | 786 | Sahiwal |

| 32 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 5,854 | 3,703,588 | 632 | Sargodha |

| 33 | Sheikhupura | Sheikhupura | 5,960 | 3,460,426 | 580 | Lahore |

| 34 | Sialkot | Sialkot | 3,016 | 3,893,672 | 1291 | Gujranwala |

| 35 | Toba Tek Singh | Toba Tek Singh | 3,252 | 2,190,015 | 673 | Faisalabad |

| 36 | Vehari | Vehari | 4,364 | 2,897,446 | 663 | Multan |

Template:Districts of Punjab (Pakistan)

Major cities[edit]

| List of major cities in Punjab | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | City | District | Population | Image |

| 1 | Lahore | Lahore | 11,126,285 |

|

| 2 | Faisalabad | Faisalabad | 3,204,726 |

|

| 3 | Rawalpindi | Rawalpindi | 2,098,231 |

|

| 4 | Gujranwala | Gujranwala | 2,027,001 |

|

| 5 | Multan | Multan | 1,871,843 |

|

| 6 | Bahawalpur | Bahawalpur | 762,111 |

|

| 7 | Sargodha | Sargodha | 659,862 |

|

| 8 | Sialkot | Sialkot | 655,852 |

|

| 9 | Sheikhupura | Sheikhupura | 473,129 |

|

| 10 | Rahim Yar Khan | Rahim Yar Khan | 420,419 |

|

| 11 | Jhang | Jhang | 414,131 |

|

| 12 | Dera Ghazi Khan | Dera Ghazi Khan | 399,064 |

|

| 13 | Gujrat | Gujrat | 390,533 |

|

| 14 | Sahiwal | Sahiwal | 389,605 |

|

| 15 | Wah Cantonment | Rawalpindi | 380,103 |

|

| Source: pbscensus 2017[87] | ||||

| This is a list of city proper populations and does not indicate metro populations. | ||||

Economy[edit]

Punjab has the largest economy in Pakistan, contributing most to the national GDP. The province's economy has quadrupled since 1972.[88] Its share of Pakistan's GDP was 54.7% in 2000 and 59% as of 2010. It is especially dominant in the service and agriculture sectors of Pakistan's economy. With its contribution ranging from 52.1% to 64.5% in the Service Sector and 56.1% to 61.5% in the agriculture sector. It is also a major manpower contributor because it has the largest pool of professionals and highly skilled (technically trained) manpower in Pakistan. It is also dominant in the manufacturing sector, though the dominance is not as huge, with historical contributions ranging from a low of 44% to a high of 52.6%.[89] In 2007, Punjab achieved a growth rate of 7.8%[90] and during the period 2002–03 to 2007–08, its economy grew at a rate of between 7% to 8% per year.[91] and during 2008–09 grew at 6% against the total GDP growth of Pakistan at 4%.

Despite the lack of a coastline, Punjab is the most industrialised province of Pakistan;[14] its manufacturing industries produce textiles, sports goods, heavy machinery, electrical appliances, surgical instruments, vehicles, auto parts, metals, sugar mill plants, aircraft, cement, agricultural machinery, bicycles and rickshaws, floor coverings, and processed foods. In 2003, the province manufactured 90% of the paper and paper boards, 71% of the fertilizers, 69% of the sugar and 40% of the cement of Pakistan.[92]

Despite its tropical wet and dry climate, extensive irrigation makes it a rich agricultural region. Its canal-irrigation system established by the British is the largest in the world. Wheat and cotton are the largest crops. Other crops include rice, sugarcane, millet, corn, oilseeds, pulses, vegetables, and fruits such as kinoo. Livestock and poultry production are also important. Despite past animosities, the rural masses in Punjab's farms continue to use the Hindu calendar for planting and harvesting.

Punjab contributes about 76% to annual food grain production in the country. Cotton and rice are important crops. They are the cash crops that contribute substantially to the national exchequer. Attaining self-sufficiency in agriculture has shifted the focus of the strategies towards small and medium farming, stress on barani areas, farms-to-market roads, electrification for tube-wells and control of water logging and salinity.

Punjab has also more than 68 thousand industrial units. There are 39,033 small and cottage industrial units. The number of textile units is 14,820. The ginning industries are 6,778. There are 7,355 units for processing of agricultural raw materials including food and feed industries.

Lahore and Gujranwala Divisions have the largest concentration of small light engineering units. The district of Sialkot excels in sports goods, surgical instruments and cutlery goods. Industrial estates are being developed by Punjab government to boost industrialization in province, Quaid e Azam Business Park Sheikhupura is one of the industrial area which is being developed near Sheikhupura on Lahore-Islamabad motorway.[94]

Punjab is also a mineral-rich province with extensive mineral deposits of coal, iron, gas, petrol, rock salt (with the second largest salt mine in the world), dolomite, gypsum, and silica-sand. The Punjab Mineral Development Corporation is running over a hundred economically viable projects. Manufacturing includes machine products, cement, plastics, and various other goods.

The incidence of poverty differs between the different regions of Punjab. With Northern and Central Punjab facing much lower levels of poverty than Western and Southern Punjab. Those living in Southern and Western Punjab are also a lot more dependent on agriculture due to lower levels of industrialisation in those regions.

Education[edit]

The literacy rate has increased greatly over the last 40 years (see the table below). Punjab has the highest Human Development Index out of all of Pakistan's provinces at 0.564.[3]

| Year | Literacy Rate |

|---|---|

| 1972 | 20.7% |

| 1981 | 27.4% |

| 1998 | 46.56% |

| 2009 | 59.6% |

| 2018 | 64.7%[95] |

This is a chart of the education market of Punjab estimated by the government in 1998.

| Qualification | Urban | Rural | Total | Enrollment Ratio(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| – | 23,019,025 | 50,602,265 | 73,621,290 | — |

| Below Primary | 3,356,173 | 11,598,039 | 14,954,212 | 100.00 |

| Primary | 6,205,929 | 18,039,707 | 24,245,636 | 79.68 |

| Middle | 5,140,148 | 10,818,764 | 15,958,912 | 46.75 |

| Matriculation | 4,624,522 | 7,119,738 | 11,744,260 | 25.07 |

| Intermediate | 1,862,239 | 1,821,681 | 3,683,920 | 9.12 |

| BA, BSc... degrees | 110,491 | 96,144 | 206,635 | 4.12 |

| MA, MSc... degrees | 1,226,914 | 764,094 | 1,991,008 | 3.84 |

| Diploma, Certificate... | 418,946 | 222,649 | 641,595 | 1.13 |

| Other qualifications | 73,663 | 121,449 | 195,112 | 0.26 |

Public universities[edit]

- Allama Iqbal Medical College, Lahore

- Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Lahore

- COMSATS Institute of Information Technology, Sahiwal

- Fatima Jinnah Women University, Rawalpindi

- Ghazi University D.G.Khan, D.G.Khan

- Government College University, Lahore

- Government College University, Faisalabad

- Gujranwala Medical College, Gujranwala

- Khawaja Fareed University of Engineering and Information Technology, Rahim Yar Khan

- King Edward Medical College, Lahore

- Kinnaird College for Women, Lahore

- Lahore College for Women University, Lahore

- Muhammad Nawaz Sharif University of Agriculture, Multan

- Muhammad Nawaz Sharif University of Engineering & Technology, Multan

- National College of Arts, Lahore

- National Textile University, Faisalabad

- NFC Institute of Engineering and Technology, Multan

- Nishtar Medical College, Multan

- Sargodha Medical College, Sargodha

- Rawalpindi Women University

- The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Bahawalpur

- University College of Agriculture, Sargodha

- University of Agriculture, Faisalabad

- University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi

- University of Education, Lahore

- University of Engineering and Technology, Lahore

- University of Engineering and Technology, Taxila

- University of Gujrat, Gujrat

- University of Health Sciences, Lahore

- University of Sahiwal

- University of Sargodha, Sargodha

- University of the Punjab, Lahore

- University of Veterinary and Animal Sciences, Lahore

- Virtual University of Pakistan, Lahore

- Women University Multan, Multan

Private universities[edit]

- Beaconhouse National University, Lahore

- Forman Christian College, Lahore

- GIFT University, Gujranwala

- Hajvery University, Lahore

- Imperial College of Business Studies, Lahore

- Institute of Management Sciences, Lahore, Pak-AIMS, Lahore

- Lahore School of Economics, Lahore

- Lahore University of Management Sciences, Lahore

- Minhaj International University, Lahore

- National University of Computer & Emerging Sciences, Lahore

- Pakistan Institute of Fashion and Design, Lahore

- Sargodha Institute of Technology, Sargodha

- University of Central Punjab, Lahore

- University of Faisalabad, Faisalabad

- University of Health Sciences, Lahore

- University of Lahore, Lahore

- University of Management and Technology, Lahore

- University of South Asia, Lahore

- University College Lahore, Lahore

- University of Wah, Wah Cantonment

- HITEC University, Taxila Cantonment

- Institute of Southern Punjab, Multan

- Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Technology, Multan

- Multan Medical and Dental College, Multan

- Lahore Garrison University, Lahore[98]

Culture[edit]

Punjab has been the cradle of civilisation since time immemorial. The ruins of Harappa show an advanced urban culture that flourished over 8000 years ago. Ancient Taxila, another historic landmark also stands out as a proof of the achievements of the area in learning, arts and crafts. The ancient Hindu Katasraj temple and the Salt Range temples are regaining attention and are in need of repair.

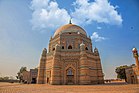

Mosques abound all over Punjab and vary in architectural style. Calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran decorate mosques and mausoleums in Punjab. The inscriptions on bricks and tiles of the mausoleum of Shah Rukn-e-Alam (1320 AD) at Multan are outstanding specimens of architectural calligraphy. The earliest existing building in South Asia with enamelled tile-work is the tomb of Shah Yusuf Gardezi (1150 AD) at Multan. A specimen of the sixteenth century tile-work at Lahore is the tomb of Sheikh Musa Ahangar, with its brilliant blue dome. The tile-work of Emperor Shah Jahan is of a richer and more elaborate nature. The pictured wall of Lahore Fort is the last line in the tile-work in the entire world.

Fairs and festivals[edit]

The culture of Punjab derives its basis from the institution of Sufi saints, who spread Islam and preached and lived the Muslim way of life. People have festivities to commemorate these traditions. The fairs and festivals of Punjab reflect the entire gamut of its folk life and cultural traditions. These mainly fall in the following categories:

Religious and seasonal fairs and festivals[edit]

Religious fairs are held on special days of Islamic significance like Eid ul-Adha, Eid-ul-Fitr, Eid-e-Milad-un-Nabi, Shahb-e-Barat, Ashura, Laylat al-Qadr and Jumu'ah-tul-Wida. The main activities on these special occasions are confined to congregational prayers and rituals. Melas are also held to mark these occasions.

Devotional fairs (Urs)[edit]

The fairs held at the shrines of Sufi saints are called urs. They generally mark the death anniversary of the saint. On these occasions, devotees assemble in large numbers and pay homage to the memory of the saint. Soul inspiring music is played and devotees dance in ecstasy. The music on these occasions is essentially folk and appealing. It forms a part of the folk music through mystic messages. The most important urs are: urs of Data Ganj Buksh at Lahore, urs of Sultan Bahu at Jhang, urs of Shah Jewna at Jhang, urs of Mian Mir at Lahore, urs of Baba Farid Ganj Shakar at Pakpattan, urs of Bahaudin Zakria at Multan, urs of Sakhi Sarwar Sultan at Dera Ghazi Khan, urs of Shah Hussain at Lahore, urs of Bulleh Shah at Kasur, urs of Imam Bari (Bari Shah Latif) at Rawalpindi-Islamabad and urs of Shah Inayat Qadri (the murrshad of Bulleh Shah) in Lahore.

A big fair/mela is organised at Jandiala Sher Khan in district Sheikhupura on the mausoleum of Syed Waris Shah who is the most loved Sufi poet of Punjab due to his classic work, Heer Ranjha. The shrine of Heer Ranjha in Jhang is one of the most visited shrines in Punjab.

Industrial and commercial fairs[edit]

Exhibitions and annual horse shows in all districts and a national horse and cattle show at Lahore are held with the official patronage. The national horse and cattle show at Lahore is the biggest festival where sports, exhibitions, and livestock competitions are held. It not only encourages and patronises agricultural products and livestock through the exhibitions of agricultural products and cattle but is also a colourful documentary on the rich cultural heritage of the province with its strong rural roots.

Other festivals[edit]

Vaisakhi, also called Besakhi, is a harvest festival to celebrate harvesting the wheat crop. Colourful festivals are held at the time of Besakhi when farmers are free to enjoy their leisure time.[99] Various literary festivals and fairs are organised in many places.[100] [101][102]

Basant is a seasonal festival and is celebrated as a spring festival of kites.[103] The day is marked by wearing yellow, eating food with yellow colouring such as potatoes with turmeric and saffron rice, and holding parties.[104]

Arts and crafts[edit]

The crafts in the Punjab are of two types: the crafts produced in the rural areas and the royal crafts.

Multan is one of the oldest regions in Pakistan where artisans create or decorate objects traditionally. Camel skin is used to produce camel-lamps, whereas camel bone is used to produce jewellery and decorative pieces. Wood crafts and blue pottery are commonly used by the artisans. "Multani Khussa", a type of shoes is created by crafting leather.[105] Hyderabad, Sindh is particularly producing wooden furniture, sports goods and embroidery items.[106]

The artisans of Sillanwali town of Punjab, Pakistan produce several types of jars which are created from wooden candy and other traditional containers. Unlike other cities of Pakistan, it is known for woodwork handicrafts.[107]

Matki earthen pot is one of the handicrafts of Pakistan, especially in Rawalpindi and Islamabad are the main regions in country where people use and craft "matki" pots.[108]

Tourism[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2021) |

The province is home to several historical sites, including the Shalimar Gardens, the Lahore Fort, the Badshahi Mosque, the Rohtas Fort and the ruins of the ancient city of Harrapa. The Anarkali Market and Jahangir's Tomb are prominent in the city of Lahore as is the Lahore Museum, while the ancient city of Taxila in the northwest was once a major centre of Buddhist and Hindu influence. Several important Sikh shrines are in the province, including the birthplace of the first Guru, Guru Nanak. (born at Nankana Sahib). There are a few famous hill stations, including Murree, Bhurban, Patriata and Fort Munro.

Katasraj Mandir is a Hindu temple complex situated in Katas village near Choa Saidanshah in the Chakwal District. Dedicated to Shiva, the temple has, according to Hindu legend, existed since the days of Mahābhārata and the Pandava brothers spent a substantial part of their exile at the site and later Krishna himself laid the foundation of this temple.[citation needed]

The Khewra Salt Mine is a tourist attraction. Tours are accompanied by guides as the mine itself is very large and the complex interconnected passages are like a maze. There is a small mosque inside the mine made from salt stone. A clinical ward with 20 beds was established in 2007[109][110] for the treatment of asthma and other respiratory diseases using salt therapy.

Music and dance[edit]

Classical music forms, such as Pakistani classical music, are an important part of the cultural wealth of the Punjab. The Muslim musicians have contributed a large number of ragas to the repository of classical music. The most common instruments used are the tabla and harmonium.

Amongst the Punjabi poets, the names of Baba Farid, Shah Hussain, Sultan Bahu, Bulleh Shah, Waris Shah and Mian Muhammad Baksh are well known. Amongst folk singers the likes of Inayat Hussain Bhatti, Tufail Niazi, Alam Lohar, Sain Marna, Mansoor Malangi, Allah Ditta Lonawala, Talib Hussain Dard, Attaullah Khan Essa Khailwi, Gamoo Tahliwala, Mamzoo Gha-lla, Akbar Jat, Arif Lohar, Ahmad Nawaz Cheena and Hamid Ali Bela are well-known. In the composition of classical ragas, there are such masters as Malika-i-Mauseequi (Queen of Music) Roshan Ara Begum, Ustad Amanat Ali Khan, Salamat Ali Khan and Ustad Fateh Ali Khan. Alam Lohar has made significant contributions to folklore and Punjabi literature, by being a very influential Punjabi folk singer from 1930 until 1979.

For the popular taste however, light music, particularly Ghazals and folk songs, which have an appeal of their own, the names of Mehdi Hassan, Ghulam Ali, Nur Jehan, Malika Pukhraj, Farida Khanum, Roshen Ara Begum, and Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan are well-known. Folk songs and dances of the Punjab reflect a wide range of moods: the rains, sowing and harvesting seasons. Luddi, Bhangra and Sammi depict the joy of living. Love legends of Heer Ranjha, Mirza Sahiban, Sohni Mahenwal and Saiful Mulk are sung in different styles.

For the most popular music from the region, Bhangra, the names of Abrar-Ul-Haq, Arif Lohar, Attaullah Khan Essa Khailwi, Jawad Ahmed, Sajjad Ali, Legacy, and Malkoo are renowned.

Folklore[edit]

Folklore songs, ballads, epics and romances are generally written and sung in the various Punjabi dialects

There are a number of folk tales that are popular in different parts of the Punjab. These are the folk tales of Mirza Sahiban, Sayful Muluk, Yusuf Zulekha, Heer Ranjha, Sohni Mahiwal, Dulla Bhatti, and Sassi Punnun. The mystic folk songs include the Kafees of Khwaja Farid in Saraiki, Punjabi and the Shalooks by Baba Farid. They also include Baits, Dohas, Lohris, Sehra, and Jugni.[111]

The most famous of the romantic love songs are Mayhiah, Dhola and Boliyan. Punjabi romantic dances include Bhangra, Giddha, Jhumar, Dhola, and Sammi.

Social issues[edit]

One social/educational issue is the status of Punjabi language. According to Manzur Ejaz, "In Central Punjab, Punjabi is neither an official language of the province nor it is used as medium of education at any level. There are only two daily newspapers published in Punjabi in the Central areas of Punjab. Only a few monthly literary magazines constitute Punjabi press in Pakistan".[112]

Notable people[edit]

- List of people from Punjab, Pakistan, also includes people born in what is today Indian Punjab but moved to Pakistan after partition

- List of Punjabi people, also includes people of Punjabi ethnicity from India and elsewhere

Gallery[edit]

Lahore Fort, a UNESCO World Heritage Site

Badshahi Mosque, Lahore

Tomb of Jahangir, Lahore

Katas Raj Temples (Sardar of Hari Singh's Haveli)

Sacred Heart Cathedral, Lahore

GPO, Lahore

Clock Tower in Sialkot.

Irrigation canals in Faisalabad

Taxila is a World Heritage Site

Major Akram Memorial, Jhelum

Different shapes of clay pots mostly made in Gujrat

Tilla Jogian Jhelum, scenic peak in Punjab considered sacred by Hindus

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ "Punjab chief secretary directs timely utilisation of funds". Bol News. 17 January 2022. Retrieved 20 January 2022.

- ↑ 2017 Census Archived 15 October 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Sub-national HDI - Area Database - Global Data Lab". hdi.globaldatalab.org. Retrieved 8 August 2021.

- ↑ "Provincial Assembly – Punjab". Archived from the original on 1 February 2009.

- ↑ "The pulse of Pakistan's growing fashion industry". The National (UAE). 11 December 2013. Archived from the original on 17 August 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Malik, Abdul-Rehman. "Bollywood to Lollywood". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 26 August 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Beck, Roger B. (1999). World History: Patterns of Interaction. Evanston, IL: McDougal Littell. ISBN 0-395-87274-X.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (2004). Within the Four Seas: The Dialogue of East and West. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-36166-4.

- ↑ Kulke, Hermann; Rothermund, Dietmar (2004). A History of India (4th ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-32919-1.

In the early centuries the centre of Buddhist scholarship was the University of Taxila.

- ↑ Balakrishnan Muniapan, Junaid M. Shaikh (2007), "Lessons in corporate governance from Kautilya's Arthashastra in ancient India", World Review of Entrepreneurship, Management and Sustainable Development 3 (1):

"Kautilya was also a Professor of Politics and Economics at Taxila University. Taxila University is one of the oldest known universities in the world and it was the chief learning centre in ancient India."

- ↑ Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 478), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"Thus the various centres of learning in different parts of the country became affiliated, as it were, to the educational centre, or the central university, of Taxila which exercised a kind of intellectual suzerainty over the wide world of letters in India."

- ↑ Radha Kumud Mookerji (2nd ed. 1951; reprint 1989), Ancient Indian Education: Brahmanical and Buddhist (p. 479), Motilal Banarsidass Publ., ISBN 81-208-0423-6:

"This shows that Taxila was a seat not of elementary, but higher, education, of colleges or a university as distinguished from schools."

- ↑ Dalrymple, William (29 June 2015). "THE GREAT DIVIDE". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on 14 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Government of the Punjab – Planning & Development Department (March 2015). "PUNJAB GROWTH STRATEGY 2018 Accelerating Economic Growth and Improving Social Outcomes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

The industrial sector of Punjab employs around 23% of the province's labour force and contributes 24% to the provincial GDP

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Farooqui, Tashkeel (20 June 2016). "Northern Punjab, urban Sindh people more prosperous than rest of country: report". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

Among the four provinces, the highest incidence of poverty is found in Sindh (45%), followed by Balochistan (44%), Khyber Pakhtukhaw (KP) (37%) and Punjab (21%)

- ↑ Islamabad Capital Territory is Pakistan's least impoverished administrative unit, but ICT is not a province. Azad Kashmir also has a rate of poverty lower than Punjab, but is not a province.

- ↑ Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12 "Sialkot District"

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12 "Rajanpur District"

- ↑ Government of the Punjab – Planning & Development Department (March 2015). "PUNJAB GROWTH STRATEGY 2018 Accelerating Economic Growth and Improving Social Outcomes" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 March 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

Punjab is among the most urbanized regions of South Asia and is experiencing a consistent and long-term demographic shift of the population to urban regions and cities, with around 40% of the province's population living in urban areas

- ↑ Gilmartin, David (1988). Empire and Islam: Punjab and the Making of Pakistan. University of California Press. pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Macauliffe, Max Arthur (2004) [1909]. The Sikh Religion – Its Gurus, Sacred Writings and Authors. India: Low Price Publications. ISBN 81-86142-31-2.

- ↑ Singh, Khushwant (2006). The Illustrated History of the Sikhs. India: Oxford University Press. pp. 12–13. ISBN 0-19-567747-1.

- ↑ Malik, Iftikhar Haider (2008). The History of Pakistan. Greenwood Publishing Group.

- ↑ "Katas Raj Temples". Temple Darshan. Archived from the original on 18 August 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ "Properties inscribed on the World Heritage List (Pakistan)". UNESCO. UNESCO. Archived from the original on 4 July 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Newspaper, the (31 March 2012). "Soan River – witness to rise and fall of many civilisations". DAWN.COM. Retrieved 25 November 2018.

- ↑ Punjab History – history of Punjab

- ↑ "Indus Valley Civilization". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ "Aryan". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency ... 1896. Archived from the original on 10 June 2016. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Gazetteer of the Bombay Presidency ..., Volume 1, Part 1-page-11

- ↑ "Guide to Historic TaxilabyProfessor Dr". www.heritage.gov.pk. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ "Battle of Hydaspes | Summary". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ "Pakistan - EARLY CIVILIZATIONS". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Allchin, Bridget; Allchin, Raymond (29 July 1982). The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521285506.

- ↑ Allchin, Bridget Gordon; Allchin, Bridget; Allchin, Raymond (29 July 1982). The Rise of Civilization in India and Pakistan. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-28550-6.

- ↑ "Rigveda 1.126:7, English translation by Ralph TH Griffith".

- ↑ Arthur Anthony Macdonell (1997). A History of Sanskrit Literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 130–. ISBN 978-81-208-0095-3.

- ↑ "UW Press: Ancient Buddhist Scrolls from Gandhara". Retrieved April 2018.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Singh. The Pearson Indian History Manual for the UPSC Civil Services Preliminary Examination. Pearson Education India. ISBN 978-81-317-1753-0.

- ↑ Antoniadis, Christos (30 March 2019). "Indo-Greeks — The Greek Buddhist Kings". Medium. Retrieved 8 June 2021.

- ↑ Grousset, Rene (1970). The Empire of the Steppes. Rutgers University Press. pp. 69–71. ISBN 0-8135-1304-9.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Levi & Sela 2010, p. 83.

- ↑ Bosworth 1963, p. 4.

- ↑ Ring, Trudy (1994). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. Taylor & Francis. p. 522.

- ↑ "Shalamar Garden". Gardens of the Mughal Empire. Archived from the original on 24 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ Advanced Study in the History of Modern India: 1707 – 1813 – Jaswant Lal Mehta – Google Books Archived 23 June 2016 at the Wayback Machine. Books.google.co.in. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik (2004). India's Historic Battles: From Alexander the Great to Kargil. Permanent Black, India. pp. 80–1. ISBN 978-81-7824-109-8.

- ↑ Elphinstone, Mountstuart (1841). History of India. John Murray, Albermarle Street. p. 276.

- ↑ For a detailed account of the battle fought, see Chapter VI of The Fall of the Moghul Empire of Hindustan Archived 10 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine by H. G. Keene.

- ↑ Mortimer, Edward, Faith and Power, (1982), p.68-70

- ↑ Grey, C. (1993). European Adventures of Northern India. Asian Educational Services. pp. 343–. ISBN 978-81-206-0853-5.

- ↑ A Collection of Papers relating to the History, Status and Powers of the Nawab of Amb. Punjab Secretariat. 1874. p. 58.

- ↑ Freedom fighters of India ISBN 8-18205-468-0 pp. 40-41

- ↑ The Punjab in 1920s – A Case study of Muslims, Zarina Salamat, Royal Book Company, Karachi, 1997. table 45, pp. 136. ISBN 969-407-230-1

- ↑ Dube, I. &. S. (2009). From ancient to modern: Religion, power, and community in India hardcover. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Punjab". Small and Medium Enterprises Development Authority. Archived from the original on 25 June 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ Choudhary Rahmat Ali (28 January 1933). "Now or Never. Are we to live or perish forever?". —. Archived from the original on 30 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ S. M. Ikram (1 January 1995). Indian Muslims and partition of India. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7156-374-6. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2011.

- ↑ "Mercury drops to freezing point – Dawn Pakistan". 6 January 2007.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 23 November 2005. Retrieved 23 November 2005.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ The figures for 1998 are from pop by province – statpak.gov.pk[dead link]. The estimates for 2012 are from Population shoots up by 47 percent since 1998 Archived 1 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Thenews.com.pk. Retrieved on 12 July 2013.

- ↑ Muslim peoples: a world ethnographic survey / Richard V. Weekes, editor-in-chief Greenwood Press 1978

- ↑ Arif, G. M. "Poverty Profile of Pakistan" (PDF). Benazir Income Support Programme. Government of Pakistan. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 December 2016. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

See Table 5, Page 12

- ↑ "CCI defers approval of census results until elections". Retrieved 2 April 2020.

- ↑ "Saraiki, a Language of Pakistan". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 25 September 2015.

- ↑ "Punjabis Without Punjabi". apnaorg.com. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "Inferiority complex declining Punjabi language: Punjab University Vice-Chancellor". PPI News Agency

- "Inferiority complex declining Punjabi language: Punjab University Vice-Chancellor | Pakistan Press International". ppinewsagency.com. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "Urdu-isation of Punjab - The Express Tribune". The Express Tribune. 4 May 2015. Archived from the original on 27 November 2016. Retrieved 30 December 2016.

- ↑ "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". The Nation. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Sufi poets can guarantee unity". The Nation. 26 August 2015. Archived from the original on 30 October 2015.

- ↑ "Supreme Court's Urdu verdict: No language can be imposed from above". The Nation. 15 September 2015. Archived from the original on 16 September 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Two-member SC bench refers Punjabi language case to CJP". Business Recorder. 14 September 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Pakistan should have adopted Punjabi as national language: Hafiz Saeed" Zee News. 6 March 2016

- "Pakistan should have adopted Punjabi as national language: Hafiz Saeed | Zee News". Zee News. 6 March 2016. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi". The Herald. 2 September 2106.

- "Mind your language—The movement for the preservation of Punjabi - People & Society - Herald". herald.dawn.com. 4 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike". The Times of India. 4 October 2015.

- "Punjabi in schools: Pro-Punjabi outfits in Pakistan threaten hunger strike - Times of India". timesofindia.indiatimes.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ "Rally for Ending the 150-year-old Ban on Education in Punjabi" The Nation. 21 February 2011.

- "Rally for ending 150-year-old 'ban on education in Punjabi". nation.com.pk. 21 February 2011. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 79.2 79.3 79.4 Nayar, Kamala Elizabeth (2012). The Punjabis in British Columbia: Location, Labour, First Nations, and Multiculturalism. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. ISBN 978-0-7735-4070-5.

- ↑ Rambo, Lewis R.; Farhadian, Charles E. (6 March 2014). The Oxford Handbook of Religious Conversion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-971354-7.

- ↑ Chhabra, G. S. (1968). Advanced History of the Punjab: Guru and post-Guru period upto Ranjit Singh. New Academic Publishing Company. p. 37.

- ↑ Lord, John (1972). The Maharajahs. Hutchinson. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-09-111050-5.

- ↑ Singh, Pritam (19 February 2008). Federalism, Nationalism and Development: India and the Punjab Economy. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-04946-2.

- ↑ "Population by Religion" (PDF). pbs.gov.pk. Pakistan Bureau of Statistics.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 "SALIENT FEATURES OF FINAL RESULTS CENSUS-2017" (PDF). Retrieved 20 May 2021.

- ↑ (in English) Internet Edition, Dawn Newspaper (10 May 2005). "Nankana becomes district". Archived from the original on 1 October 2005. Retrieved 14 April 2006.

No data is yet available on the recently created district of Nankana. - ↑ "DISTRICT WISE CENSUS RESULTS CENSUS 2017" (PDF). www.pbscensus.gov.pk. Archived from the original (PDF) on 29 August 2017.

- ↑ "World Bank Document" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 May 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2019.

- ↑ "Provincial Accounts of Pakistan: Methodology and Estimates 1973–2000" (PDF). Retrieved 19 December 2019.[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "The News International: Latest, Breaking, Pakistan, Sports and Video News". Archived from the original on 28 July 2020. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ A PricewaterhouseCoopers study released in 2009, surveying the 2008 GDP of the top cities in the world, calculated Faisalabad's GDP (PPP) at $35 billion. The city was third in Pakistan behind Karachi ($78 billion) and Lahore ($40 billion). Faisalabad's GDP is projected to rise to $37 billion in 2025 at a growth rate of 5.7%, higher than the growth rates of 5.5% and 5.6% predicted for Karachi and Lahore.[2][ "PricewaterhouseCoopers Media Centre". Ukmediacentre.pwc.com. 1 June 2005.]– Last Paragraph[permanent dead link]

- ↑ "Punjab Gateway" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 July 2007.

- ↑ [email protected], ZAHID IKRAM. "Industrial Zone Punjab, Pakistan". findpk.com. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011.

- ↑ "PIEDMC - Punjab Industrial Estate Development and Management Company".

- ↑ Razzaque, Ayesha (4 November 2020). "The road to school". The International News. Retrieved 30 November 2020.

- ↑ "Pakistan: where and who are the world's illiterates?; Background paper for the Education for all global monitoring report 2006: literacy for life; 2005" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 December 2009.

- ↑ "Rural women uphold Pakistan's literacy rate". The Express Tribune. 15 February 2011. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ "Lahore Garrison University".

- ↑ Kalim, M. Siddiq (29 December 2017). As memories come. Ferozsons. ISBN 9789690020062. Archived from the original on 29 December 2017 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Pakistan Today (8 April 2016) Punjabi Parchar spreads colours of love at Visakhi Mela Archived 20 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "A fair dedicated to animal lovers". 20 April 2009. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017.

- ↑ Agnes Ziegler, Akhtar Mummunka (2006) The final Frontier: unique photographs of Pakistan. Sang-e-Meel Publications Ziegler, Agnes; Mummunka, Akhtar (2006). The final Frontier: Unique photographs of Pakistan. ISBN 9789693517736. Archived from the original on 12 April 2017. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ↑ The Sikh World: An Encyclopedia Survey of Sikh Religion and Culture: Ramesh Chander Dogra and Urmila Dogra; ISBN 81-7476-443-7

- ↑ Khawar Mumtaz, Yameema Mitha, Bilquis Tahira (2003) Pakistan: Tradition and Change. Oxfam [1] Archived 6 January 2018 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Handicraft-makers: Multan chamber seeks support for artisans". The Express Tribune. 7 February 2017.

- ↑ "The vibrancy of our culture". www.thenews.com.pk.

- ↑ "Sillanwali admired for grooming handicrafts". The Nation. 12 May 2011.

- ↑ "Trend of earthen water pitchers persists in twin cities". The Express Tribune. 20 June 2019.

- ↑ "Salt mine resort for asthma patients". Dawn. 27 March 2007. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ↑ Shahzad, Khurram (26 March 2010). "Asthma treatment in Pakistani salt mine". The Telegraph. Archived from the original on 10 July 2012. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- ↑ "punjabilok.com". Archived from the original on 20 September 2008. Retrieved 22 April 2015.

- ↑ Sarah Veach, Katy Williamson, Punjabi Culture and Language Manual Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine (archived), Texas State University, p. 6, retrieved 14 May 2016.

Bibliography[edit]

- Pakistan Narcotics Control Board (1986), National survey on drug abuse in Pakistan, The University of Michigan

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: ref duplicates default (link)

External links[edit]

- www

.punjab .gov .pk - Punjab, Pakistan at Curlie

- Guide to Punjab, Pakistan

Template:Punjab, Pakistan topics Template:Five rivers of the Punjab Template:Administrative units of Pakistan Template:Districts of Punjab, Pakistan