Mihirakula

| Mihirakula | |

|---|---|

| Ruler of the Alchon Huns | |

| |

| Reign | 515–540 CE |

| Predecessor | Toramana |

| Successor | Toramana II Pravarasena |

| Religion | Shaivism |

Mihirakula (Gupta script: ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() , Mi-hi-ra-ku-la, Chinese: 摩酰逻矩罗 Mo-hi-lo-kiu-lo), sometimes referred to as Mihiragula or Mahiragula, was the second and last Alchon Hun king of northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent between 502 and 530 CE.[6] He was a son of and successor to Toramana of Huna heritage. His father ruled the Indian part of the Hephthalite Empire. Mihirakula ruled from his capital of Sagala (modern-day Sialkot, Pakistan).[7][8]

, Mi-hi-ra-ku-la, Chinese: 摩酰逻矩罗 Mo-hi-lo-kiu-lo), sometimes referred to as Mihiragula or Mahiragula, was the second and last Alchon Hun king of northwestern region of the Indian subcontinent between 502 and 530 CE.[6] He was a son of and successor to Toramana of Huna heritage. His father ruled the Indian part of the Hephthalite Empire. Mihirakula ruled from his capital of Sagala (modern-day Sialkot, Pakistan).[7][8]

In around 520 CE, the Chinese monk Song Yun met with Mihirakula.[6] According to the 7th-century travelogue of the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim and student Xuanzang, Mihirakula ruled several hundreds of years before his visit, was initially interested in Buddhism, and sought a Buddhist teacher from monasteries in his domain. They did not send him a learned Buddhist scholar. Feeling insulted, he became anti-Buddhist and destroyed the monasteries in his kingdom.[better source needed][9][10]

Mihirakula is believed to have patronized Shaivism tradition of Hinduism.[11] The Rajatarangini calls him cruel, "a man of violent acts and resembling kala (death)", who ruled "the land then overrun by hordes of mlecchas (foreigners)."[12] According to the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Song Yun, Mihirakula "does not believe in any religion", the Brahmins who live in his kingdom and read their sacred texts do not like him, his people were unhappy.[13]

The Buddhist texts record Mihirakula as extremely cruel and bad mannered,[11][6][14] the one who destroyed Buddhist sites, ruined monasteries, killed monks.[15] The Hindu kings Yashodharman and Gupta Empire rulers, between 525 and 532 CE, likely by 530 CE, reversed Mihirakula's campaign and ended the Mihirakula era.[16][17]

Etymology[edit]

The name "Mihirakula" is most likely of Iranian origin and may have the meaning "Mithra's Begotten", as translated by Janos Harmatta.[18] According to Harold Walter Bailey: "A name like Toramana and his son's name Mihirakula interpreted by North Iranian (and not by Western Iranian) are clearly Iranian".[19]

Description[edit]

According to Krishna Chandra Sagar, the Huna king Toramana was cruel and barbaric, his son Mihirakula even more so, during their rule.[16] Mihirakula had conquered Sindh by 520 CE, had a large elephant and cavalry-driven army. Mihirakula destroyed Buddhist sites, ruined monasteries, according to Sagar. Yashodharman, sometime between 525 and 532 CE, reversed Mihirakula's campaign and triggered the end of Mihirakula and the Alchon Huns.[16][11]

Mihirakula issued coins, like the Kushana era kings, showing Oesho or Shiva. This suggests that he may have patronized Shaivism, or just replaced his image in the traditional Kushana-style way of making coins at the mints. Other scholars state that there are many legends surrounding this era and historical facts are difficult to ascertain. Except for rare Kashmiri texts such as Rajatarangini, he is hardly acknowledged and never praised in Hindu texts. The 12th-century Rajatarangini includes him as one of the kings in regional history, then calls him cruel, "a man of violent acts and resembling kala (death)", who ruled "the land then overrun by hordes of mlecchas (foreigners)."[12] Contradictory evidence is found in the memoir left by the Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Song Yun, reputed to have met Mihirakula. He states that Mihirakula "does not believe in any religion", that the Brahmins who live in his kingdom and read their sacred texts do not like him, his people were exhausted and unhappy with his wars and destruction.[13]

Xuanzang[edit]

The 7th-century Chinese pilgrim Xuanzang (Hsuan Tsang) left a travelogue. This text includes a hearsay story about Mihirakula, who he says ruled several hundred years ago from his capital of Sagala (now Sialkot, Pakistan).[9] This estimate is incorrect, as there is only about 100 year difference between Mihirakula rule and Xuanzang pilgrimage in India. Xuanzang states that after coming to power, Mihirakula asked Buddhist monasteries in his domain to send him a scholar to teach Buddhism. However, based on the reputation of his father and his own, the monks and scholars did not go. They sent a novice. This angered Mihirakula. He then ordered the destruction of the Buddhist religion:[9]

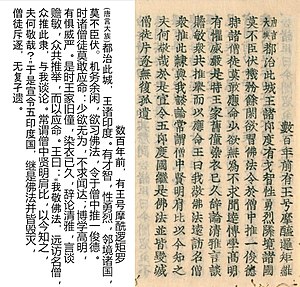

Xuanzang about Mihirakula (introductory part about his change of mind about Buddhism). Excerpt of the Southern Song edition of 1132 CE.[20]

Xuanzang about Mihirakula (introductory part about his change of mind about Buddhism). Excerpt of the Southern Song edition of 1132 CE.[20]Some centuries ago there was a king called Mihirakula (摩酰逻矩罗, Mo-hi-lo-kiu-lo), who established his authority in this town and ruled over India. He was of quick talent, and naturally brave. He subdued all the neighbouring provinces without exception. In his intervals of leisure he desired to examine the law of Buddha, and he commanded that one among the priests of superior talent should wait on him. Now it happened that none of the priests dared to attend to his command. Those who had few desires and were content, did not care about distinction; those of superior learning and high renown despised the royal bounty (glitter). At this time there was an old servant in the king's household who had long worn the religious garments. He was of distinguished ability and able to enter on discussion, -and was very eloquent. The priests put him forward in answer to the royal appeal. The king said, " I have a respect for the law of Buddha, and I invited from far any renowned priest (to come and instruct me), and now the congregation have put forward this servant to discuss with me. I always thought that amongst the priests there were men of illustrious ability; after what has happened today what further respect can I have for the priesthood ?" He then issued an edict to destroy all the priests through the five Indies (lit. 五印度国 "the five countries of India"), to overthrow the law of Buddha, and leave nothing remaining.

The cruel deeds and the news of destruction by Mihirakula spread to other Indian kingdoms. The king of Magadha announced a war against him. Mihirakula proceeded to invade eastern kingdoms including Magadha. He was defeated and captured by the Gupta king Narasimhagupta Baladitya.[9] The Magadha king tried him and declared the right punishment for Mihirakula to be execution. However, Baladitya's mother intervened and argued against capital punishment.[17][23]

Mihirakula's life was thus spared. Meanwhile, during Mihirakula stay in prison, his associate had already completed a coup and taken power in Sagala. After his release from Magadha, Mihirahula arrived in the kingdom of Kashmira, where the local king gave him a territory to govern. Mihirakula then usurped power over Kashmira.[17] He assassinated the king of Kashmira, and thereafter annexed Gandhara after a surprise assassination of its king and a slaughter of all its ministers. He looted the country and carried the spoils to his capital. He killed more people and also demolished 1600 stupas and monasteries, states Xuanzang.[9] Mihirakula's campaign of destruction and his attempt to regain his Bactria-encompassing empire came to an end after the central Indian king Yashodharman defeated him.[17] According to Xuanzang, Mihirakula died a sudden death. After his death, the Buddhist scholars in this land declared that "he will fall in the deepest hell of incessant suffering and rotate [in the wheel of rebirth] without end" (Li Rongxi translation).[9]

According to Xuanzang's travelogue, despite Mihirakula destructive campaign during his rule, thousands of monasteries of different Buddhist schools – both Hinayana and Mahayana, as well as monks and scholars were thriving in northwestern regions of the subcontinent when he visited (629–645 CE), including the countries of Udyana, Balura, Taksasila, Gandhara, Kashmira and Rajapura. He studied for months in several of these places, and two years in a Kashmira monastery.[24][25] Even in the 6th-century capital Sagala of Mihirakula, Xuanzang's 7th-century travelogue states that there is a monastery with more than hundred monks studying Hinayana Buddhism, along with a 200 feet high stupa next to it (compare Guanyin of Mount Xiqiao). Around the capital, to its northwest and northeast, he describes some ruins as well as several other major ancient stupas from Ashoka's era, all over 200 feet.[9]

As per archeological findings, the Greco-Buddhist art disappeared after this period. The period followed a revival of hinduism and the numerous Shahi dynasties of this region did not patronize Buddhism.[26]

Cosmas Indicopleustes[edit]

The 6th-century Alexandrian traveler Cosmas Indicopleustes states that the Hephthalites in India reached the zenith of its power under "Gollas", which is thought to be the same as Mihirakula from the last part of his name.[27][28]

Higher up in India, that is, farther to the north, are the White Huns. The one called Gollas when going to war takes with him, it is said, no fewer than two thousand elephants, and a great force of cavalry. He is the lord of India, and oppressing the people forces them to pay tribute.

Gwalior inscription[edit]

The Gwalior inscription issued in the 15th regnal year created by Matricheta in a Surya temple, mentions Mihirakula. It confirms that Mihirakula rule extended to Gwalior.[citation needed]

Mandasor Pillar Inscriptions of Yasodharman[edit]

In 528 Mihirakula suffered a defeat in the Battle of Sondani by the Aulikara dynasty Hindu king Yashodharman, an event that is partly the subject of the Mandasor pillar inscription of Yasodharman. The defeat ended the Alchon Hun era in India.[29][16]

Critical studies[edit]

Template:Alchon Huns Medieval era Chinese Buddhist pilgrims depict the early 6th-century Mihirakula as a tyrant and persecutor of their religion.[30] However, according to Jason Neelis – a scholar of Buddhist studies and religious history, all evidence including those in their travelogue suggests that, despite his rule in Punjab, Gandhara and Kashmir regions, there was "no negative impact on the growth of Buddhist monasteries" in these regions over previous centuries.[30] Some early Indian studies, such as by D.C. Sircar, have incorrectly used coins or a questionable prashasti inscription of the Aulikaras (unrelated to Mihirakula) to declare him a Shaiva ruler, and declare him as selectively persecuting the Buddhists. The Aulikara inscription is actually referring to Shiva as the family deity of the Aulikaras, states Neelis.[30] This has perpetuated John Marshall's incorrect conjecture that "Mihirakula destroyed Buddhism in Gandhara", wiping out the Buddhist monasteries in the northwest. Later archaeological studies affirm that the major Buddhist monastery at Harwan – near Srinagar, Kashmir – was "built" during this period.[30] According to Shōshin Kuwayama – a Buddhist history scholar, there is no evidence whatsoever that Mihirakula destroyed Buddhism in Gandhara, there is plenty of evidence that he did not and that it continued to grow and thrive in and around northwest Indian subcontinent for many centuries after Mihirakula's death. Mihirakula was cruel, but his cruelty did not discriminate based on religion, nor did it destroy or reverse Buddhism in the northwest.[30][31][32]

The travelogue of Xuanzang states that initially Mihirakula was interested in learning about Buddhism, and asked the monks to send him a teacher; the monks sent him a novice servant for the purpose. He felt insulted. This incident is said to have turned Mihirakula virulently anti-Buddhist.[33]

Historian Upinder Singh has raised some questions over the anti-Buddhist reputation of Mihirakula while considering these episodes of violence:-

Was this reputation based on actual religious persecution? Or was Mihirakula cast into the role of a cruel anti-Buddhist king because one of his arch political opponents, king Baladitya of Magadha (sometimes identified with a later Gupta emperor Narasimhagupta), at whose hands he apparently suffered a crushing defeat, was an ardent patron of the Buddhist sangha? The interesting thing is that ninth- and tenth-century Jaina texts describe Mihirakula as a wicked, oppressive tyrant who was anti-Jaina. Are the textual references evidence of active political persecution and violence? Or are they merely expressions of resentment at a lack of royal patronage and support? Are they recastings of political conflicts into religious molds?[34]

Singh considers the symbolism on his coinage (some of his copper coins have a bull on the reverse with the inscription "The bull should be victorious"),[35] and some inscriptions, as possible evidence that Mihirakula was inclined toward Shaivism. She adds that this and other material evidence is "confusing" yet significant that "such perceptions of violent royal persecution and oppression on religious lines existed". Even if the accounts of Mihirakula persecution is true or exaggerated, it was against the general trends of royal religious policy of that period.[34]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ The "h" (

) is an early variant of the Gupta script.

) is an early variant of the Gupta script.

- ↑ The "h" (

) is an early variant of the Gupta script.

) is an early variant of the Gupta script.

- ↑ Verma, Thakur Prasad (2018). The Imperial Maukharis: History of Imperial Maukharis of Kanauj and Harshavardhana (in हिन्दी). Notion Press. p. 264. ISBN 9781643248813.

- ↑ Sircar, D. C. (2008). Studies in Indian Coins. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 376. ISBN 9788120829732.

- ↑ Tandon, Pankaj (2013). Notes on the Evolution of Alchon Coins Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society, No. 216, Summer. Oriental Numismatic Society. pp. 24–34. also Coinindia Alchon Coins (for an exact description of this coin type)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Grousset, Rene (1970), The Empire of the Steppes, Rutgers University Press, pp. 71–72, ISBN 0-8135-1304-9

- ↑ Bakker, Hans (16 July 2014). The World of the Skandapurāṇa. BRILL. ISBN 9789004277144.

- ↑ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations: A.D. 250 to 750. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 9788120815407.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Li Rongxi (1996), The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley, pp. 97–100

- ↑ Singh, Upinder (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 241. ISBN 978-0-674-97527-9.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Mihirakula, Encyclopaedia Britannica

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Daryaee, T. (2021). King of the Seven Climes: A History of the Ancient Iranian World (3000 BCE - 651 CE). Ancient Iran Series. Brill. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-90-04-46064-5.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Chavannes, E. (1903). "VOYAGE DE SONG YUN DANS L'UDYĀNA ET LE GANDHĀRA". Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. 3 (3): 416–417, context:379–441 with footnotes. doi:10.3406/befeo.1903.1235. JSTOR 43729722.

- ↑ Behrendt, Kurt A. (2004). Handbuch der Orientalistik. BRILL. ISBN 9789004135956.

- ↑ A. L. Basham (1967). The Wonder That Was India. Public Resource.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 Foreign Influence on Ancient India by Krishna Chandra Sagar p.216

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 242–244. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- ↑ Janos Harmatta, "The Rise of the Old Persian Empire: Cyrus the Great," AAASH Acta Antiqua Acadamie Scientiarum Hungaricae 19, 197, pp. 4-15.

- ↑ Bailey, H. W. (1982). Culture of the Sakas in Ancient Iranian Khotan. Caravan Books. p. 91.

- ↑ Facsimile of the original Southern Song edition: "古籍欣赏 Xuanzang". gmzm.org.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Xuan, Zang; Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist records of the Western world. London : Trübner. pp. 167 ff.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Xuan, Zang; Beal, Samuel (1884). Si-Yu-Ki: Buddhist records of the Western world. London : Trübner. pp. 167 ff.

- ↑

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Original Chinese: 数百年前,有王号摩酰逻矩罗,(唐言大族。)都治此城,王诸印度。有才智,性勇烈,邻境诸国,莫不臣伏。机务余闲,欲习佛法,令于僧中推一俊德。时诸僧徒莫敢应命:少欲无为,不求闻达;博学高明,有惧威严。是时王家旧僮,染衣已久,辞论清雅,言谈赡敏,众共推举,而以应命。王曰:"我敬佛法,远访名僧,众推此隶,与我谈论。常谓僧中贤明肩比,以今知之,夫何敬哉?"于是宣令五印度国,继是佛法并皆毁灭,僧徒斥逐,无复孑遗 [1]

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. Original Chinese: 数百年前,有王号摩酰逻矩罗,(唐言大族。)都治此城,王诸印度。有才智,性勇烈,邻境诸国,莫不臣伏。机务余闲,欲习佛法,令于僧中推一俊德。时诸僧徒莫敢应命:少欲无为,不求闻达;博学高明,有惧威严。是时王家旧僮,染衣已久,辞论清雅,言谈赡敏,众共推举,而以应命。王曰:"我敬佛法,远访名僧,众推此隶,与我谈论。常谓僧中贤明肩比,以今知之,夫何敬哉?"于是宣令五印度国,继是佛法并皆毁灭,僧徒斥逐,无复孑遗 [1]

- ↑ Louis Renou; Jean Filliozat (1957). Political history of India from the earliest times to the 7th century A.D. by J. Filliozat. Susil. pp. 176–183.

- ↑ Li Rongxi (1996), The Great Tang Dynasty Record of the Western Regions, Bukkyo Dendo Kyokai and Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley, pp. 71–96

- ↑ Yung-hsi 1959, p. 57–72.

- ↑ Heirman, Ann; Peter Bumbacher, Stephan (11 May 2007). "BUDDHISM IN GANDHARA:7. Zenith and Decline of Buddhism in Central Asia". The Spread of Buddhism. Leiden: BRILL. p. 60. ISBN 978-9004158306.

- ↑ Dani, Ahmad Hasan (1999). History of Civilizations of Central Asia: The crossroads of civilizations, A.D. 250 to 750. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. p. 142. ISBN 8120815408. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ Indian History. Tata McGraw-Hill Education. p. 396. ISBN 9781259063237.

- ↑ Ojha, N.K. (2001). The Aulikaras of Central India: History and Inscriptions, Chandigarh: Arun Publishing House, ISBN 81-85212-78-3, p.52

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Neelis, Jason (2010). Early Buddhist Transmission and Trade Networks: Mobility and Exchange Within and Beyond the Northwestern Borderlands of South Asia. Dynamics in the History of Religions. Brill. pp. 166–170 with footnotes. ISBN 978-90-04-18159-5.

- ↑ S Kuwayama, The Hephthalites in Tokhharistan and Northwest India, Zinbun. Memoire of the Research Institute for Humanistic Studies, (24), 89-134

- ↑ Shosin Kuwayama (2002), Across the Hindukush of the First Millennium: a collection of the papers, Institute for Research in Humanities, Kyoto University Press, pp. 7, 38–41 Quote: "However, the Hephthalite destruction of Buddhist activities in the Northwest really is a sheer conjecture fancifully created Marshall, and does not bear any historical authenticity".

- ↑ Upinder Singh (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. p. 241. ISBN 9780674981287.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Upinder Singh (2017). Political Violence in Ancient India. Harvard University Press. pp. 241–242. ISBN 9780674981287.

- ↑ Alram, Michael. "The Countenance of the Other". Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna.

Bibliography[edit]

- Yung-hsi, Li (1959). The Life of Hsuan Tsang by Huili (Translated). Chinese Buddhist Association, Beijing.

External links[edit]

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Toramana |

King of the Alchon Huns 515-540 |

Succeeded by Toramana II |