Vedas: Difference between revisions

(Created page with " {{Infobox religious text | religion = Hinduism | image = Four vedas|280px | alt = Four Vedas | language = Vedic Sanskrit | caption =...") |

m (Removed empty portal template using script) |

||

| (4 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Short description|Oldest scriptures of Hinduism}} | |||

{{redirect-multi|2|Veda|Vedic}} | |||

{{EngvarB|date=March 2015}} | |||

{{Use dmy dates|date=March 2015}} | |||

{{Infobox religious text | {{Infobox religious text | ||

| religion = [[Hinduism]] | | religion = [[Hinduism]] | ||

| Line 6: | Line 11: | ||

| language = [[Vedic Sanskrit]] | | language = [[Vedic Sanskrit]] | ||

| caption = Four Vedas | | caption = Four Vedas | ||

| period = | | period = {{circa|1500}}–1200 BCE ([[Rigveda]]),<ref name="Flood 2003 69" />{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}}<br />c. 1200–900 BCE ([[Yajurveda]], [[Samaveda]], [[Atharvaveda]])<ref name="Flood 2003 69"/>{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=37}} | ||

| verses = 20,379 mantras<ref>{{cite web |title=Construction of the Vedas |website=VedicGranth.Org |url=https://sites.google.com/a/vedicgranth.org/www/what_are_vedic_granth/the-four-veda/interpretation-and-more/construction-of-the-vedas?mobile=true}}</ref> | | verses = 20,379 mantras<ref>{{cite web |title=Construction of the Vedas |website=VedicGranth.Org |url=https://sites.google.com/a/vedicgranth.org/www/what_are_vedic_granth/the-four-veda/interpretation-and-more/construction-of-the-vedas?mobile=true |access-date=3 July 2020 |archive-date=17 July 2021 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20210717035126/https://sites.google.com/a/vedicgranth.org/www/what_are_vedic_granth/the-four-veda/interpretation-and-more/construction-of-the-vedas?mobile=true |url-status=dead }}</ref> | ||

}} | | wikisource = The Vedas | ||

{{Hindu scriptures}} | |||

}}{{Hindu scriptures}} | |||

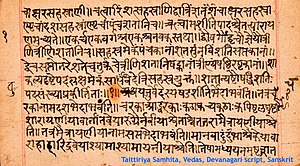

[[FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png|thumb|upright=1.2|The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''[[Atharvaveda]]''.]] | [[FIle:Atharva-Veda samhita page 471 illustration.png|thumb|upright=1.2|The Vedas are ancient Sanskrit texts of Hinduism. Above: A page from the ''[[Atharvaveda]]''.]] | ||

The '''Vedas''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|v|eɪ|d|ə|z | The '''Vedas''' ({{IPAc-en|ˈ|v|eɪ|d|ə|z}}<ref>[http://www.dictionary.com/browse/veda "Veda"]. ''[[Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary]]''.</ref> or {{IPAc-en|ˈ|v|iː|d|ə|z}},<ref>''[[Oxford English Dictionary]]'' Online (accessed 8 April 2023)</ref> {{IAST3|veda}}, {{Lang-sa|वेदः|lit=knowledge}}) are a large body of [[religious texts]] originating in [[ancient India]]. Composed in [[Vedic Sanskrit]], the texts constitute the oldest layer of [[Sanskrit literature]] and the oldest [[Hindu texts|scriptures]] of [[Hinduism]].<ref>see e.g. {{Harvnb|Radhakrishnan|Moore|1957|p=3}}; {{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|p=68}}; {{Harvnb|MacDonell|2004|pp=29–39}}.</ref><ref>''Sanskrit literature'' (2003) in Philip's Encyclopedia. Accessed 2007-08-09</ref><ref>Sanujit Ghose (2011). "[http://www.worldhistory.org/article/230/ Religious Developments in Ancient India]" in ''World History Encyclopedia''.</ref> | ||

There are four Vedas: the [[Rigveda]], the [[Yajurveda]], the [[Samaveda]] and the [[Atharvaveda]].<ref name=gflood/><ref>Bloomfield, M. The Atharvaveda and the Gopatha-Brahmana, (Grundriss der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde II.1.b.) Strassburg 1899; Gonda, J. ''A history of Indian literature'': I.1 Vedic literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas); I.2 The Ritual Sutras. Wiesbaden 1975, 1977</ref> Each Veda has four subdivisions – the [[Samhita]]s ([[mantra]]s and [[benediction]]s), the [[ | There are four Vedas: the [[Rigveda]], the [[Yajurveda]], the [[Samaveda]] and the [[Atharvaveda]].<ref name=gflood/><ref>Bloomfield, M. The Atharvaveda and the Gopatha-Brahmana, (Grundriss der Indo-Arischen Philologie und Altertumskunde II.1.b.) Strassburg 1899; Gonda, J. ''A history of Indian literature'': I.1 Vedic literature (Samhitas and Brahmanas); I.2 The Ritual Sutras. Wiesbaden 1975, 1977</ref> Each Veda has four subdivisions – the [[Samhita]]s ([[mantra]]s and [[benediction]]s), the [[Aranyaka]]s (text on rituals, ceremonies, sacrifices and symbolic-sacrifices), the [[Brahmanas]] (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the [[Upanishads]] (texts discussing [[meditation]], philosophy and spiritual knowledge).<ref name=gflood>Gavin Flood (1996), ''An Introduction to Hinduism'', Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-521-43878-0}}, pp. 35–39</ref><ref name="A Bhattacharya 2006 pp. 8–14">A Bhattacharya (2006), ''Hindu Dharma: Introduction to Scriptures and Theology'', {{ISBN|978-0-595-38455-6}}, pp. 8–14; George M. Williams (2003), Handbook of Hindu Mythology, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-19-533261-2}}, p. 285</ref><ref name="Jan Gonda 1975">Jan Gonda (1975), Vedic Literature: (Saṃhitās and Brāhmaṇas), Otto Harrassowitz Verlag, {{ISBN|978-3-447-01603-2}}</ref> Some scholars add a fifth category – the [[Upasana]]s (worship).{{sfn|Bhattacharya|2006|pp=8–14}}{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|pp=351–357}} The texts of the Upanishads discuss ideas akin to the heterodox ''sramana''-traditions.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=82}} | ||

Vedas are ''{{IAST|[[śruti]]}}'' ("what is heard"),{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=887}} distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called ''{{IAST|[[smṛti]]}}'' ("what is remembered"). Hindus consider the Vedas to be ''[[apauruṣeya]]'', which means "not of a man, superhuman"{{sfn|Apte|1965|loc="apauruSeya"}} and "impersonal, authorless,"{{sfn|Sharma|2011|pp=196–197}}{{sfn|Westerhoff|2009|p=290}}{{sfn|Todd|2013|p=128}} revelations of sacred sounds and texts heard by ancient [[sage (philosophy)|sages]] after intense meditation.{{sfn|Pollock|2011|pp=41–58}}{{sfn|Scharfe|2002|pp=13–14}} | Vedas are ''{{IAST|[[śruti]]}}'' ("what is heard"),{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=887}} distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called ''{{IAST|[[smṛti]]}}'' ("what is remembered"). Hindus consider the Vedas to be ''[[apauruṣeya]]'', which means "not of a man, superhuman"{{sfn|Apte|1965|loc="apauruSeya"}} and "impersonal, authorless,"{{sfn|Sharma|2011|pp=196–197}}{{sfn|Westerhoff|2009|p=290}}{{sfn|Todd|2013|p=128}} revelations of sacred sounds and texts heard by ancient [[sage (philosophy)|sages]] after intense meditation.{{sfn|Pollock|2011|pp=41–58}}{{sfn|Scharfe|2002|pp=13–14}} | ||

The Vedas have been orally transmitted since the 2nd millennium BCE with the help of elaborate [[Vedic chant|mnemonic techniques]].{{sfn|Wood|2007}}{{sfn|Hexam|2011|p=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Dwyer|2013}} The mantras, the oldest part of the Vedas, are recited in the modern age for their phonology rather than the semantics, and are considered to be "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} | The Vedas have been orally transmitted since the 2nd millennium BCE with the help of elaborate [[Vedic chant|mnemonic techniques]].{{sfn|Wood|2007}}{{sfn|Hexam|2011|p=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Dwyer|2013}} The mantras, the oldest part of the Vedas, are recited in the modern age for their [[phonology]] rather than the [[semantics]], and are considered to be "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} By reciting them the [[cosmos]] is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} | ||

The various [[Indian philosophy|Indian philosophies]] and [[Hindu denominations]] have taken differing positions on the Vedas | The various [[Indian philosophy|Indian philosophies]] and [[Hindu denominations]] have taken differing positions on the Vedas. Schools of Indian philosophy that acknowledge the importance or primal authority of the Vedas comprise [[Hindu philosophy]] specifically and are together classified as the six "orthodox" ([[Āstika and nāstika|āstika]]) schools.{{refn|group=note|name="Freschi_2012"}} However, [[śramaṇa]] traditions, such as [[Charvaka]], [[Ajivika]], [[Buddhism]], and [[Jainism]], which did not regard the Vedas as authoritative, are referred to as "heterodox" or "non-orthodox" ([[Āstika and nāstika|nāstika]]) schools.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=82}}<ref name="EB_astika">[http://www.britannica.com/topic/astika "astika"] and [http://www.britannica.com/topic/nastika "nastika"]. ''[[Encyclopædia Britannica Online]]'', 20 April 2016.</ref> | ||

==Etymology and usage== | ==Etymology and usage== | ||

The [[Sanskrit]] word ''{{IAST|véda}}'' "knowledge, wisdom" is derived from the root ''vid-'' "to know". This is reconstructed as being derived from the [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] root ''{{PIE|*u̯eid-}}'', meaning "see" or "know."{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1048.html p. 1015]}}{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=856}} | The [[Sanskrit]] word ''{{IAST|véda}}'' "knowledge, wisdom" is derived from the root ''vid-'' "to know". This is reconstructed as being derived from the [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] root ''{{PIE|*u̯eid-}}'', meaning "see" or "know."{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1048.html p. 1015]}}{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=856}} | ||

The noun is from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''{{PIE|*u̯eidos}}'', cognate to [[Greek language|Greek]] {{lang|grc|(ϝ)εἶδος}} "aspect", "form" . This is not to be confused with the homonymous 1st and 3rd person singular perfect tense ''{{IAST|véda}}'', cognate to Greek {{lang|grc|(ϝ)οἶδα}} ''(w)oida'' "I know". Root cognates are Greek [[idea|ἰδέα]], | The noun is from [[Proto-Indo-European language|Proto-Indo-European]] ''{{PIE|*u̯eidos}}'', cognate to [[Greek language|Greek]] {{lang|grc|(ϝ)εἶδος}} "aspect", "form" . This is not to be confused with the homonymous 1st and 3rd person singular perfect tense ''{{IAST|véda}}'', cognate to Greek {{lang|grc|(ϝ)οἶδα}} ''(w)oida'' "I know". Root cognates are Greek [[idea|ἰδέα]], English ''[[wit]]'', etc., [[Latin]] ''videō'' "I see", German ''wissen'' "to know" etc.<ref>see e.g. Pokorny's 1959 ''[[Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch]]'' s.v. ''{{PIE|u̯(e)id-}}''²; Rix' ''[[Lexikon der indogermanischen Verben]]'', ''{{PIE|u̯ei̯d-}}''.</ref> | ||

The Sanskrit term ''{{IAST|veda}}'' as a common noun means "knowledge".{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1048.html p. 1015]}} The term in some contexts, such as hymn 10.93.11 of the ''[[Rigveda]]'', means "obtaining or finding wealth, property",{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1050.html p. 1017 (2nd Column)]}} while in some others it means "a bunch of grass together" as in a broom or for [[Homa (ritual)|ritual fire]].{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1050.html p. 1017 (3rd Column)]}} | The Sanskrit term ''{{IAST|veda}}'' as a common noun means "knowledge".{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1048.html p. 1015]}} The term in some contexts, such as hymn 10.93.11 of the ''[[Rigveda]]'', means "obtaining or finding wealth, property",{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1050.html p. 1017 (2nd Column)]}} while in some others it means "a bunch of grass together" as in a broom or for [[Homa (ritual)|ritual fire]].{{sfn|Monier-Williams|1899|loc=[http://www.ibiblio.org/sripedia/ebooks/mw/1000/mw__1050.html p. 1017 (3rd Column)]}} | ||

Vedas are called ''Maṛai'' or ''Vaymoli'' in parts of South India. Marai literally means "hidden, a secret, mystery". But the Tamil [[Naan Marai]] mentioned in [[Tolkāppiyam|Tholkappiam]] | Vedas are called ''Maṛai'' or ''Vaymoli'' in parts of South India. Marai literally means "hidden, a secret, mystery". But the Tamil [[Naan Marai]] mentioned in [[Tolkāppiyam|Tholkappiam]] is not Sanskrit Vedas.<ref>Vasudha Narayanan (1994), The Vernacular Veda: Revelation, Recitation, and Ritual, University of South Carolina Press, {{ISBN|978-0-87249-965-2}}, p. 194</ref><ref name="John Carman 1989 pp. 259–261">John Carman (1989), The Tamil Veda: Pillan's Interpretation of the Tiruvaymoli, University of Chicago Press, {{ISBN|978-0-226-09305-5}}, pp. 259–261</ref> In some parts of [[South India]] (e.g. the [[Iyengar]] communities), the word ''veda'' is used in the [[Tamil language|Tamil]] writings of the [[Alvars|Alvar]] saints. Such writings include the [[Naalayira Divya Prabandham]] (aka [[Tiruvaymoli]]).<ref name="Vasudha Narayanan 1994 pp. 43, 117">Vasudha Narayanan (1994), The Vernacular Veda: Revelation, Recitation, and Ritual, University of South Carolina Press, {{ISBN|978-0-87249-965-2}}, pp. 43, 117–119</ref> | ||

==Vedic texts== | ==Vedic texts== | ||

| Line 36: | Line 42: | ||

===Vedic Sanskrit corpus=== | ===Vedic Sanskrit corpus=== | ||

The term "Vedic texts" is used in two distinct meanings: | The term "Vedic texts" is used in two distinct meanings: | ||

# Texts composed in [[Vedic Sanskrit]] during the [[Vedic period]] ([[Iron Age India]]) | # Texts composed in [[Vedic Sanskrit]] during the [[Vedic period]] ([[Iron Age in India|Iron Age India]]) | ||

# Any text considered as "connected to the Vedas" or a "corollary of the Vedas"<ref>according to [[International Society for Krishna Consciousness|ISKCON]], [http://hinduism.iskcon.com/tradition/1105.htm Hindu Sacred Texts], "Hindus themselves often use the term to describe anything connected to the Vedas and their corollaries (e.g. Vedic culture)."</ref> | # Any text considered as "connected to the Vedas" or a "corollary of the Vedas"<ref>according to [[International Society for Krishna Consciousness|ISKCON]], [http://hinduism.iskcon.com/tradition/1105.htm Hindu Sacred Texts], "Hindus themselves often use the term to describe anything connected to the Vedas and their corollaries (e.g. Vedic culture)."</ref> | ||

The corpus of [[Vedic Sanskrit]] texts includes: | The corpus of [[Vedic Sanskrit]] texts includes: | ||

* The [[Samhitas]] (Sanskrit ''{{IAST|saṃhitā}}'', "collection"), are collections of metric texts ("[[mantra]]s"). There are four "Vedic" Samhitas: the [[Rigveda|Rig-Veda]], [[Yajurveda|Yajur-Veda]], [[Samaveda|Sama-Veda]] and [[Atharvaveda|Atharva-Veda]], most of which are available in several [[recension]]s (''{{IAST|śākhā}}''). In some contexts, the term ''Veda'' is used to refer only to these Samhitas, the collection of mantras. This is the oldest layer of Vedic texts, which were composed between circa | * The [[Samhitas]] (Sanskrit ''{{IAST|saṃhitā}}'', "collection"), are collections of metric texts ("[[mantra]]s"). There are four "Vedic" Samhitas: the [[Rigveda|Rig-Veda]], [[Yajurveda|Yajur-Veda]], [[Samaveda|Sama-Veda]] and [[Atharvaveda|Atharva-Veda]], most of which are available in several [[recension]]s (''{{IAST|śākhā}}''). In some contexts, the term ''Veda'' is used to refer only to these Samhitas, the collection of mantras. This is the oldest layer of Vedic texts, which were composed between circa 1500–1200 BCE (Rig Veda book 2–9),{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}} and 1200–900 BCE for the other ''Samhitas''. The Samhitas contain invocations to deities like [[Indra]] and [[Agni]], "to secure their benediction for success in battles or for welfare of the clan."{{sfn|Prasad|2020|p=150}} The complete corpus of Vedic mantras as collected in [[Maurice Bloomfield|Bloomfield]]'s ''Vedic Concordance'' (1907) consists of some 89,000 [[pada (Hindu mythology)|padas]] ([[Foot (prosody)|metrical feet]]), of which 72,000 occur in the four Samhitas.<ref>37,575 are Rigvedic. Of the remaining, 34,857 appear in the other three Samhitas, and 16,405 are known only from Brahmanas, Upanishads or Sutras</ref> | ||

* The [[Brahmana]]s are prose texts that comment and explain the solemn rituals as well as expound on their meaning and many connected themes. Each of the Brahmanas is associated with one of the Samhitas or its recensions.{{sfn|Klostermaier|1994|pp=67–69}}<ref name="ebri"/> The oldest dated to about 900 BCE, while the youngest Brahmanas (such as the [[Shatapatha Brahmana]]), were complete by about 700 BCE.<ref name=mw>[[Michael Witzel]], "Tracing the Vedic dialects" in ''Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes'' ed. Caillat, Paris, 1989, 97–265.</ref><ref name=bcp>Biswas et al (1989), Cosmic Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-521-34354-1}}, pp. 42–43</ref> The Brahmanas may either form separate texts or can be partly integrated into the text of the Samhitas. They may also include the Aranyakas and Upanishads. | * The [[Brahmana]]s are prose texts that comment and explain the solemn rituals as well as expound on their meaning and many connected themes. Each of the Brahmanas is associated with one of the Samhitas or its recensions.{{sfn|Klostermaier|1994|pp=67–69}}<ref name="ebri"/> The oldest dated to about 900 BCE, while the youngest Brahmanas (such as the [[Shatapatha Brahmana]]), were complete by about 700 BCE.<ref name=mw>[[Michael Witzel]], "Tracing the Vedic dialects" in ''Dialectes dans les litteratures Indo-Aryennes'' ed. Caillat, Paris, 1989, 97–265.</ref><ref name=bcp>Biswas et al (1989), Cosmic Perspectives, Cambridge University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-521-34354-1}}, pp. 42–43</ref> The Brahmanas may either form separate texts or can be partly integrated into the text of the Samhitas. They may also include the Aranyakas and Upanishads. | ||

* The [[Aranyaka]]s, "wilderness texts" or "forest treaties", were composed by people who meditated in the woods as recluses and are the third part of the Vedas. The texts contain discussions and interpretations of ceremonies, from ritualistic to symbolic meta-ritualistic points of view.<ref name="jago"/> It is frequently read in secondary literature. | * The [[Aranyaka]]s, "wilderness texts" or "forest treaties", were composed by people who meditated in the woods as recluses and are the third part of the Vedas. The texts contain discussions and interpretations of ceremonies, from ritualistic to symbolic meta-ritualistic points of view.<ref name="jago"/> It is frequently read in secondary literature. | ||

* Older [[ | * Older [[Principal Upanishads]] ([[Brihadaranyaka Upanishad|{{IAST|Bṛhadāraṇyaka}}]], [[Chandogya Upanishad|Chandogya]], [[Katha Upanishad|{{IAST|Kaṭha}}]], [[Kena Upanishad|Kena]], [[Aitareya Upanishad|Aitareya]], and others),<ref name="Flood 2003 69">{{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|p=69}}.</ref><ref name="Michaels 2004 51">{{Harvnb|Michaels|2004|p=51}}.</ref> composed between 800 BCE and the end of the Vedic period.<ref name="Mahony1998p271">{{cite book|author=William K. Mahony|title=The Artful Universe: An Introduction to the Vedic Religious Imagination|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=B1KR_kE5ZYoC |year=1998|publisher=State University of New York Press |isbn=978-0-7914-3579-3 |page=271}}</ref> The [[Upanishads]] are largely philosophical works, some in dialogue form. They are the foundation of Hindu philosophical thought and its diverse traditions.<ref name=wendydoniger/><ref>Wiman Dissanayake (1993), Self as Body in Asian Theory and Practice (Editors: Thomas P. Kasulis et al.), State University of New York Press, {{ISBN|978-0-7914-1080-6}}, p. 39; Quote: "The Upanishads form the foundations of Hindu philosophical thought and the central theme of the Upanishads is the identity of Atman and Brahman, or the inner self and the cosmic self.";<br />Michael McDowell and Nathan Brown (2009), World Religions, Penguin, {{ISBN|978-1-59257-846-7}}, pp. 208–210</ref> Of the Vedic corpus, they alone are widely known, and the central ideas of the Upanishads are still influential in Hinduism.<ref name=wendydoniger>Wendy Doniger (1990), Textual Sources for the Study of Hinduism, 1st Edition, University of Chicago Press, {{ISBN|978-0-226-61847-0}}, pp. 2–3; Quote: "The Upanishads supply the basis of later Hindu philosophy; they alone of the Vedic corpus are widely known and quoted by most well-educated Hindus, and their central ideas have also become a part of the spiritual arsenal of rank-and-file Hindus."</ref><ref>[[Patrick Olivelle]] (2014), The Early Upanisads, Oxford University Press, {{ISBN|978-0-19-535242-9}}, p. 3; Quote: "Even though theoretically the whole of vedic corpus is accepted as revealed truth [shruti], in reality it is the Upanishads that have continued to influence the life and thought of the various religious traditions that we have come to call Hindu. Upanishads are the scriptures par excellence of Hinduism".</ref> | ||

* The texts considered "Vedic" in the sense of "corollaries of the Vedas" are less clearly defined, and may include numerous post-Vedic texts such as the later [[Upanishads]] and the [[Sūtra|Sutra literature]], such as [[Shrauta Sutras]] and [[Kalpa (Vedanga)#Gryhasutras|Gryha Sutras]], which are smriti texts. Together, the Vedas and these Sutras form part of the Vedic Sanskrit corpus.<ref name="Flood 2003 69"/>{{refn|group=note|For a table of all Vedic texts see {{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|pp=100–101}}.}}{{refn|group=note|The Vedic Sanskrit corpus is incorporated in ''[[A Vedic Word Concordance]]'' (''{{IAST|Vaidika-Padānukrama-Koṣa}}'') prepared from 1930 under Vishva Bandhu, and published in five volumes in 1935–1965. Its scope extends to about 400 texts, including the entire Vedic Sanskrit corpus besides some "sub-Vedic" texts. Volume I: Samhitas, Volume II: Brahmanas and Aranyakas, Volume III: Upanishads, Volume IV: Vedangas; A revised edition, extending to about 1800 pages, was published in 1973–1976.}} | * The texts considered "Vedic" in the sense of "corollaries of the Vedas" are less clearly defined, and may include numerous post-Vedic texts such as the later [[Upanishads]] and the [[Sūtra|Sutra literature]], such as [[Shrauta Sutras]] and [[Kalpa (Vedanga)#Gryhasutras|Gryha Sutras]], which are smriti texts. Together, the Vedas and these Sutras form part of the Vedic Sanskrit corpus.<ref name="Flood 2003 69"/>{{refn|group=note|For a table of all Vedic texts see {{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|pp=100–101}}.}}{{refn|group=note|The Vedic Sanskrit corpus is incorporated in ''[[A Vedic Word Concordance]]'' (''{{IAST|Vaidika-Padānukrama-Koṣa}}'') prepared from 1930 under Vishva Bandhu, and published in five volumes in 1935–1965. Its scope extends to about 400 texts, including the entire Vedic Sanskrit corpus besides some "sub-Vedic" texts. Volume I: Samhitas, Volume II: Brahmanas and Aranyakas, Volume III: Upanishads, Volume IV: Vedangas; A revised edition, extending to about 1800 pages, was published in 1973–1976.}} | ||

| Line 49: | Line 55: | ||

===Śruti and smriti === | ===Śruti and smriti === | ||

Vedas are ''{{IAST|[[śruti]]}}'' "what is heard"),{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=887}} distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called ''{{IAST|[[smṛti]]}}'' ("what is remembered"). This indigenous system of categorization was adopted by [[Max Müller]] and, while it is subject to some debate, it is still widely used. As Axel Michaels explains: | Vedas are ''{{IAST|[[śruti]]}}'' ("what is heard"),{{sfn|Apte|1965|p=887}} distinguishing them from other religious texts, which are called ''{{IAST|[[smṛti]]}}'' ("what is remembered"). This indigenous system of categorization was adopted by [[Max Müller]] and, while it is subject to some debate, it is still widely used. As [[Axel Michaels]] explains: | ||

{{ | {{blockquote|These classifications are often not tenable for linguistic and formal reasons: There is not only ''one'' collection at any one time, but rather several handed down in separate Vedic schools; Upanişads [...] are sometimes not to be distinguished from {{IAST|Āraṇyakas}} [...]; {{IAST|Brāhmaṇas}} contain older strata of language attributed to the {{IAST|Saṃhitās}}; there are various dialects and locally prominent traditions of the Vedic schools. Nevertheless, it is advisable to stick to the division adopted by Max Müller because it follows the Indian tradition, conveys the historical sequence fairly accurately, and underlies the current editions, translations, and monographs on Vedic literature."<ref name="Michaels 2004 51"/>}} | ||

Among the widely known śrutis include the Vedas and their embedded texts—the [[Samhita]]s, the [[Upanishad]]s, the [[Brahmana]]s and the [[Aranyaka]]s. The well-known smṛtis include [[Bhagavad Gita]], [[Bhagavata Purana]] and the epics [[Ramayana]] and [[Mahabharata]], amongst others. | |||

===Authorship=== | ===Authorship=== | ||

Hindus consider the Vedas to be ''[[ | Hindus consider the Vedas to be ''[[apauruṣeyā]]'', which means "not of a man, superhuman"{{sfn|Apte|1965|loc="apauruSeya"}} and "impersonal, authorless."{{sfn|Sharma|2011|pp=196–197}}{{sfn|Westerhoff|2009|p=290}}{{sfn|Todd|2013|p=128}} The Vedas, for orthodox Indian theologians, are considered revelations seen by ancient [[sage (philosophy)|sages]] after intense meditation, and texts that have been more carefully preserved since ancient times.{{sfn|Pollock|2011|pp=41–58}}{{sfn|Scharfe|2002|pp=13–14}} In the Hindu Epic ''[[Mahabharata]]'', the creation of Vedas is credited to [[Brahma]].<ref>[https://books.google.com/books?id=8XO3Im3OMi8C&dq=brahma+created+vedas&pg=PA86 Seer of the Fifth Veda: Kr̥ṣṇa Dvaipāyana Vyāsa in the Mahābhārata] Bruce M. Sullivan, Motilal Banarsidass, pp. 85–86</ref> The Vedic hymns themselves assert that they were skillfully created by ''[[Rishi]]s'' (sages), after inspired creativity, just as a carpenter builds a chariot.{{sfn|Scharfe|2002|pp=13–14}}{{refn|group=note|"As a skilled craftsman makes a car, a singer I, Mighty One! this hymn for thee have fashioned. If thou, O Agni, God, accept it gladly, may we obtain thereby the heavenly Waters". – ''Rigveda 5.2.11'', Translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith<ref>{{cite web|title=The Rig Veda/Mandala 5/Hymn 2|url= https://en.wikisource.org/wiki/The_Rig_Veda/Mandala_5/Hymn_2}}</ref>}} | ||

The oldest part of the Rig Veda ''Samhita'' was orally composed in north-western India ([[Punjab, India|Punjab]]) between {{circa}} 1500 and 1200 | The oldest part of the Rig Veda ''Samhita'' was orally composed in north-western India ([[Punjab, India|Punjab]]) between {{circa}} 1500 and 1200 BCE,{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}} while book 10 of the Rig Veda, and the other Samhitas were composed between 1200 and 900 BCE more eastward, between the [[Yamuna]] and the [[Ganges]] rivers, the heartland of [[Aryavarta]] and the [[Kuru Kingdom]] (c. 1200 – c. 900 BCE).{{sfn|Witzel|1995|p=4}}{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=37}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|p=49}}{{sfn|Witzel|2008|p=68}}{{sfn|Frazier|2011|p=344}} The "circum-Vedic" texts, as well as the [[shakha|redaction]] of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000–500 BCE. | ||

According to tradition, ''[[Vyasa]]'' is the compiler of the Vedas, who arranged the four kinds of ''mantras'' into four ''Samhitas'' (Collections).{{sfn|Holdrege|2012|pp=249, 250}}{{sfn|Dalal|2014|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=UCEoAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT16 16]}} | According to tradition, ''[[Vyasa]]'' is the compiler of the Vedas, who arranged the four kinds of ''mantras'' into four ''Samhitas'' (Collections).{{sfn|Holdrege|2012|pp=249, 250}}{{sfn|Dalal|2014|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=UCEoAwAAQBAJ&pg=PT16 16]}} | ||

==Chronology, transmission and interpretation== | ==Chronology, transmission, and interpretation== | ||

{{See also|Vedic period}} | {{See also|Vedic period}} | ||

===Chronology=== | ===Chronology=== | ||

The Vedas are among the [[Ancient literature|oldest sacred texts]].{{sfn|Dutt|2006|p=36 | The Vedas are among the [[Ancient literature|oldest sacred texts]].{{sfn|Dutt|2006|p=36}} The bulk of the Rigveda Samhita was composed in the northwestern region (Punjab) of the [[Indian subcontinent]], most likely between {{circa}} 1500 and 1200 BCE,{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=37}}{{sfn|Witzel|1995|p=4}}{{sfn|Anthony|2007|p=454}} although a wider approximation of {{circa}} 1700–1100 BCE has also been given.{{sfn|Oberlies|1998|p=158}}{{sfn|Kumar|2014|p=179}}{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}} The other three Samhitas are considered to date from the time of the [[Kuru Kingdom]], approximately {{circa}} 1200–900 BCE.<ref name="Flood 2003 69" /> The "circum-Vedic" texts, as well as the [[shakha|redaction]] of the Samhitas, date to c. 1000–500 BCE, resulting in a [[Vedic period]], spanning the mid 2nd to mid 1st millennium BCE, or the [[Bronze Age India|Late Bronze Age]] and the [[Iron Age India|Iron Age]].{{refn|group=note|[[Gavin Flood]] sums up mainstream estimates, according to which the Rigveda was compiled from as early as 1500 BCE over a period of several centuries.{{sfn|Flood|1996|p=37}}}} | ||

The Vedic period reaches its peak only after the composition of the mantra texts, with the establishment of the various [[shakha]]s all over Northern India which annotated the mantra [[samhitas]] with [[Brahmana]] discussions of their meaning, and reaches its end in the age of [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] and [[Pāṇini|Panini]] and the rise of the [[Mahajanapadas]] (archaeologically, [[Northern Black Polished Ware]]). Michael Witzel gives a time span of c. 1500 to c. 500–400 BCE. Witzel makes special reference to the Near Eastern [[Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni|Mitanni material]] of the 14th century BCE, the only epigraphic record of Indo-Aryan contemporary to the Rigvedic period. He gives 150 BCE ([[Patañjali]]) as a [[Terminus post quem|terminus ante quem]] for all Vedic Sanskrit literature, and 1200 BCE (the early [[Iron Age India|Iron Age]]) as [[terminus post quem]] for the Atharvaveda.{{sfn|Witzel|2003|p=68}} | The Vedic period reaches its peak only after the composition of the mantra texts, with the establishment of the various [[shakha]]s all over Northern India which annotated the mantra [[samhitas]] with [[Brahmana]] discussions of their meaning, and reaches its end in the age of [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] and [[Pāṇini|Panini]] and the rise of the [[Mahajanapadas]] (archaeologically, [[Northern Black Polished Ware]]). [[Michael Witzel]] gives a time span of c. 1500 to c. 500–400 BCE. Witzel makes special reference to the Near Eastern [[Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni|Mitanni material]] of the 14th century BCE, the only epigraphic record of Indo-Aryan contemporary to the Rigvedic period. He gives 150 BCE ([[Patañjali]]) as a [[Terminus post quem|terminus ante quem]] for all Vedic Sanskrit literature, and 1200 BCE (the early [[Iron Age India|Iron Age]]) as [[terminus post quem]] for the Atharvaveda.{{sfn|Witzel|2003|p=68}} | ||

===Transmission=== | ===Transmission=== | ||

The Vedas were orally transmitted since their composition in the [[Vedic period]] for several millennia.<ref name="Witzel2003"/>{{sfn|Wood|2007}}{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|p=344}} The authoritative transmission{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} of the Vedas is by an [[oral tradition]] in a ''[[sampradaya]]'' from father to son or from teacher (''guru'') to student (''shishya''),{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|p=344}}{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}}{{sfn|Hexam|2011|p=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Pruthi|2004|p=286}}{{sfn|Wood|2007}} believed to be initiated by the Vedic ''[[rishis]]'' who heard the [[Nāda yoga|primordial sounds]].{{sfn|Holdrege|2012|p=165}} Only this tradition, embodied by a living teacher, can teach the correct pronunciation of the sounds and explain hidden meanings, in a way the "dead and entombed manuscript" cannot do.{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}}{{refn|group=note|{{harvnb|Broo|2016|p=92}} quotes Harold G. Coward and K. Kunjunni Raja.}} As Leela Prasad states, "According to [[Adi Shankara|Shankara]], the "correct tradition" (''sampradaya'') has as much authority as the written Shastra," explaining that the tradition "bears the authority to clarify and provide direction in the application of knowledge."{{sfn|Prasad|2007 | The Vedas were orally transmitted since their composition in the [[Vedic period]] for several millennia.<ref name="Witzel2003"/>{{sfn|Wood|2007}}{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|p=344}} The authoritative transmission{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} of the Vedas is by an [[oral tradition]] in a ''[[sampradaya]]'' from father to son or from teacher (''guru'') to student (''shishya''),{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|p=344}}{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}}{{sfn|Hexam|2011|p=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Pruthi|2004|p=286}}{{sfn|Wood|2007}} believed to be initiated by the Vedic ''[[rishis]]'' who heard the [[Nāda yoga|primordial sounds]].{{sfn|Holdrege|2012|p=165}} Only this tradition, embodied by a living teacher, can teach the correct pronunciation of the sounds and explain hidden meanings, in a way the "dead and entombed manuscript" cannot do.{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}}{{refn|group=note|{{harvnb|Broo|2016|p=92}} quotes Harold G. Coward and K. Kunjunni Raja.}} As Leela Prasad states, "According to [[Adi Shankara|Shankara]], the "correct tradition" (''sampradaya'') has as much authority as the written Shastra," explaining that the tradition "bears the authority to clarify and provide direction in the application of knowledge."{{sfn|Prasad|2007|p=125}} | ||

The emphasis in this transmission{{refn|group=note|Of the complete Veda, by ''pāțha-śālā'' (priestly schools), as distinguished from the transmission in the ''pūjā'', the daily services.{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|pp=344–345}}}} is on the "proper articulation and pronunciation of the Vedic sounds, | The emphasis in this transmission{{refn|group=note|Of the complete Veda, by ''pāțha-śālā'' (priestly schools), as distinguished from the transmission in the ''pūjā'', the daily services.{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|pp=344–345}}}} is on the "proper articulation and pronunciation of the Vedic sounds", as prescribed in the [[Shiksha]],{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|p=345}} the [[Vedanga]] (Vedic study) of sound as uttered in a Vedic recitation,{{sfn|Banerji|1989|pp=323–324}}{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|pp=477–495}} mastering the texts "literally forward and backward in fully acoustic fashion."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} Houben and Rath note that the Vedic textual tradition cannot simply be characterized as oral, "since it also depends significantly on a memory culture."{{sfn|Rath|2012|p=22}} The Vedas were preserved with precision with the help of elaborate [[Vedic chant|mnemonic techniques]],{{sfn|Wood|2007}}{{sfn|Hexam|2011|p=chapter 8}}{{sfn|Dwyer|2013}} such as memorizing the texts in eleven different modes of recitation (''[[patha]]s''),{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} using the alphabet as a [[Art of memory|mnemotechnical device]],{{sfn|Griffiths|1999|p=122}}{{sfn|Rath|2012|p=19}}<!-- **START OF NOTE** -->{{refn|group=note|Several authors refer to the Chinese Buddhist Monk I-Tsing, who visited India in the 7th century to retrieve Buddhist texts and gave examples of mnemonic techniques used in India:{{sfn|Griffiths|1999|p=122}} "In India there are two traditional ways in which one can attain great intellectual power. Firstly by repeatedly committing to memory the intellect is developed; secondly the alphabet fixes (to) one's ideas. By this way, after a practice of ten days or a month, a student feels his thoughts rise like a fountain, and can commit to memory whatever he has heard once."{{sfn|Rath|2012|p=19}}{{sfn|Griffiths|1999|p=122}}}}<!-- **END OF NOTE** --> "matching physical movements (such as nodding the head) with particular sounds and chanting in a group"{{sfn|Doniger|2010|p=106}} and visualizing sounds by using ''[[mudra]]s'' (hand signs).{{Sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|p=479}} This provided an additional visual confirmation, and also an alternate means to check the reading integrity by the audience, in addition to the audible means.{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|p=479}} Houben and Rath note that a strong "memory culture" existed in ancient India when texts were transmitted orally, before the advent of writing in the early first millennium CE.{{sfn|Rath|2012|p=19}} According to [[Frits Staal|Staal]], criticising the [[Jack Goody|Goody]]-Watt hypothesis "according to which literacy is more reliable than orality,"{{sfn|Schiffman|2012|p=171}} this tradition of oral transmission "is closely related to Indian forms of science," and "by far the more remarkable" than the relatively recent tradition of written transmission.<!-- **START OF NOTE** -->{{refn|group=note|name="Staal_discoveries"|Staal: [this tradition of oral transmission is] "by far the more remarkable [than the relatively recent tradition of written transmission], not merely because it is characteristically Indian and unlike anything we find elsewhere, but also because it has led to scientific discoveries that are of enduring interest and from which the contemporary West still has much to learn." {{harvtxt|Schiffman|2012|p=171}}, quoting {{harvtxt|Staal|1986|p=27}}<br />Staal argued that the ancient Indian grammarians, especially [[Pāṇini]], had completely mastered methods of linguistic theory not rediscovered again until the 1950s and the applications of modern mathematical logic to linguistics by [[Noam Chomsky]]. (Chomsky himself has said that the first [[generative grammar]] in the modern sense was Panini's grammar).<ref name=front>[http://www.frontlineonnet.com/fl1825/18250150.htm An event in Kolkata] {{webarchive |url=https://web.archive.org/web/20120510134321/http://www.frontlineonnet.com/fl1825/18250150.htm |date=May 10, 2012 }}, [[Frontline (magazine)|Frontline]]</ref> These early Indian methods allowed the construction of discrete, potentially infinite generative systems. Remarkably, these early linguistic systems were codified orally, though writing was then used to develop them in some way. The formal basis for Panini's methods involved the use of "auxiliary" markers, rediscovered in the 1930s by the logician [[Emil Post]].<ref>{{cite journal|author=Kadvany, John|title=Positional Value and Linguistic Recursion|journal=Journal of Indian Philosophy|year=2007|pages=487–520|volume=35|issue=5–6|doi=10.1007/s10781-007-9025-5|citeseerx=10.1.1.565.2083|s2cid=52885600}}</ref>}}<!-- **END OF NOTE** --> | ||

While according to Mookerji [[Nirukta|understanding the meaning]] (''vedarthajnana''{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=328}} or ''[[artha]]-[[Buddhi|bodha]]''{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=35}}{{refn|group=note|name="artha"}}) of the words of the Vedas was part of the [[Vedanga|Vedic learning]],{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=35}} Holdrege and other Indologists{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}} have noted that in the transmission of the ''Samhitas'' the emphasis is on the phonology of the sounds (''[[śabda]]'') and not on the meaning (''[[artha]]'') of the mantras.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}} Already at the end of the Vedic period their original meaning had become obscure for "ordinary people,"{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{refn|group=note|name="Kautas"|{{harvnb|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}: "Kautas, a teacher mentioned in the ''[[Nirukta]]'' by ''[[Yāska]]'' (ca. 500 BCE), a work devoted to an etymology of Vedic words that were no longer understood by ordinary people, held that the word of the Veda was no longer perceived as meaningful "normal" speech but as a fixed sequence of sounds, whose meaning was obscure beyond recovery."<br><br>The tenth through twelfth volumes of the first Prapathaka of the [[Chandogya Upanishad]] (800-600 BCE) describe a legend about priests and it criticizes how they go about reciting verses and singing hymns without any idea what they mean or the divine principle they signify.<ref name=pauldeussen112>Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-81-208-1468-4}}, pages 80-84</ref>}} and ''[[nirukta]]s'', etymological compendia, were developed to preserve and clarify the original meaning of many Sanskrit words.{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{sfn|Jackson|2016|p="Sayana, Vidyaranya’s brother"}} According to Staal, as referenced by Holdrege, though the mantras may have a discursive meaning, when the mantras are recited in the Vedic rituals "they are disengaged from their original context and are employed in ways that have little or nothing to do with their meaning."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}{{refn|group=note|According to Holdrege, ''srotriyas'' (a group of male Brahmin reciters who are masters of ''sruti''{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}}) "frequently do not understand what they recite" when reciting the ''Samhitas'', merely preserving the sound of the text.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}}} The words of the mantras are "themselves sacred,"{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=346–347}} and "do not constitute [[Speech act|linguistic utterances]]."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} Instead, as Klostermaier notes, in their application in Vedic rituals they become [[Magic (supernatural)|magical]] sounds, "means to an end."{{refn|group=note|Klostermaier: "''Brahman'', derived from the root ''bŗh'' <nowiki>=</nowiki> to grow, to become great, was originally identical with the Vedic word, that makes people prosper: words were the pricipan means to approach the gods who dwelled in a different sphere. It was not a big step from this notion of "reified [[Speech act|speech-act]]" to that "of the speech-act being looked at implicitly and explicitly as a means to an end." {{harvnb|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}} quotes {{harvnb|Deshpande|1990|p=4}}.}} Holdrege notes that there are scarce commentaries on the meaning of the mantras, in contrast to the number of commentaries on the Brahmanas and Upanishads, but states that the lack of emphasis on the "discursive meaning does not necessarily imply that they are meaningless."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=346,347}} In the Brahmanical perspective, the sounds have their own meaning, mantras are considered as "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base. As long as the purity of the sounds is preserved, the recitation of the ''mantras'' will be efficacious, irrespective of whether their discursive meaning is understood by human beings."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}}{{refn|group=note|name="Coward2008_mimamsa"|{{harvnb|Coward|2008|p=114}}: "For the [[Mimamsa]] the ultimate reality is nothing other than the eternal words of the Vedas. They did not accept the existence of a single supreme creator god, who might have composed the Veda. According to the Mimamsa, gods named in the Vedas have no existence apart from the mantras that speak their names. The power of the gods, then, is nothing other than the power of the mantras that name them."}} Frazier further notes that "later Vedic texts sought deeper understanding of the reasons the rituals worked," which indicates that the Brahmin communities considered study to be a "process of understanding."{{sfn|Frazier|2011|p=34}} | While according to Mookerji [[Nirukta|understanding the meaning]] (''vedarthajnana''{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=328}} or ''[[artha]]-[[Buddhi|bodha]]''{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=35}}{{refn|group=note|name="artha"}}) of the words of the Vedas was part of the [[Vedanga|Vedic learning]],{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=35}} Holdrege and other Indologists{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}} have noted that in the transmission of the ''Samhitas'' the emphasis is on the phonology of the sounds (''[[śabda]]'') and not on the meaning (''[[artha]]'') of the mantras.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{sfn|Broo|2016|p=92}} Already at the end of the Vedic period their original meaning had become obscure for "ordinary people,"{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{refn|group=note|name="Kautas"|{{harvnb|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}: "Kautas, a teacher mentioned in the ''[[Nirukta]]'' by ''[[Yāska]]'' (ca. 500 BCE), a work devoted to an etymology of Vedic words that were no longer understood by ordinary people, held that the word of the Veda was no longer perceived as meaningful "normal" speech but as a fixed sequence of sounds, whose meaning was obscure beyond recovery."<br /><br />The tenth through twelfth volumes of the first Prapathaka of the [[Chandogya Upanishad]] (800-600 BCE) describe a legend about priests and it criticizes how they go about reciting verses and singing hymns without any idea what they mean or the divine principle they signify.<ref name=pauldeussen112>Paul Deussen, Sixty Upanishads of the Veda, Volume 1, Motilal Banarsidass, {{ISBN|978-81-208-1468-4}}, pages 80-84</ref>}} and ''[[nirukta]]s'', etymological compendia, were developed to preserve and clarify the original meaning of many Sanskrit words.{{sfn|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}}{{sfn|Jackson|2016|p="Sayana, Vidyaranya’s brother"}} According to Staal, as referenced by Holdrege, though the mantras may have a discursive meaning, when the mantras are recited in the Vedic rituals "they are disengaged from their original context and are employed in ways that have little or nothing to do with their meaning."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}{{refn|group=note|According to Holdrege, ''srotriyas'' (a group of male Brahmin reciters who are masters of ''sruti''{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}}) "frequently do not understand what they recite" when reciting the ''Samhitas'', merely preserving the sound of the text.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=346}}}} The words of the mantras are "themselves sacred,"{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=346–347}} and "do not constitute [[Speech act|linguistic utterances]]."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} Instead, as Klostermaier notes, in their application in Vedic rituals they become [[Magic (supernatural)|magical]] sounds, "means to an end."{{refn|group=note|Klostermaier: "''Brahman'', derived from the root ''bŗh'' <nowiki>=</nowiki> to grow, to become great, was originally identical with the Vedic word, that makes people prosper: words were the pricipan means to approach the gods who dwelled in a different sphere. It was not a big step from this notion of "reified [[Speech act|speech-act]]" to that "of the speech-act being looked at implicitly and explicitly as a means to an end." {{harvnb|Klostermaier|2007|p=55}} quotes {{harvnb|Deshpande|1990|p=4}}.}} Holdrege notes that there are scarce commentaries on the meaning of the mantras, in contrast to the number of commentaries on the Brahmanas and Upanishads, but states that the lack of emphasis on the "discursive meaning does not necessarily imply that they are meaningless."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=346,347}} In the Brahmanical perspective, the sounds have their own meaning, mantras are considered as "primordial rhythms of creation", preceding the forms to which they refer.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}} By reciting them the cosmos is regenerated, "by enlivening and nourishing the forms of creation at their base. As long as the purity of the sounds is preserved, the recitation of the ''mantras'' will be efficacious, irrespective of whether their discursive meaning is understood by human beings."{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=347}}{{refn|group=note|name="Coward2008_mimamsa"|{{harvnb|Coward|2008|p=114}}: "For the [[Mimamsa]] the ultimate reality is nothing other than the eternal words of the Vedas. They did not accept the existence of a single supreme creator god, who might have composed the Veda. According to the Mimamsa, gods named in the Vedas have no existence apart from the mantras that speak their names. The power of the gods, then, is nothing other than the power of the mantras that name them."}} Frazier further notes that "later Vedic texts sought deeper understanding of the reasons the rituals worked," which indicates that the Brahmin communities considered study to be a "process of understanding."{{sfn|Frazier|2011|p=34}} | ||

A literary tradition is traceable in post-Vedic times, after the rise of [[Buddhism]] in the [[Maurya Empire|Maurya period]],{{refn|group=note|The early Buddhist texts are also generally believed to be of oral tradition, with the first Pali Canon written many centuries after the death of the Buddha.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Donald S. Lopez Jr. |year=1995|title= Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna|journal= Numen|volume= 42 |number= 1 |pages= 21–47 |jstor= 3270278|doi=10.1163/1568527952598800 |hdl=2027.42/43799 |url= https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/43799/1/11076_1995_Article_1568527952598800.pdf|hdl-access= free }}</ref>}} perhaps earliest in the [[Kanvas|Kanva]] recension of the Yajurveda about the 1st century BCE; however oral tradition of transmission remained active.<ref name="Witzel2003">{{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|p=69}}; For oral composition and oral transmission for "many hundreds of years" before being written down, see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=76}}.</ref> [[Jack Goody]] has argued for an earlier literary tradition, concluding that the Vedas bear hallmarks of a literate culture along with oral transmission,{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|p=192}}{{sfn|Goody|1987}} but Goody's views have been strongly criticised by Falk, Lopez Jr,. and Staal, though they have also found some support.{{sfn|Lopez | A literary tradition is traceable in post-Vedic times, after the rise of [[Buddhism]] in the [[Maurya Empire|Maurya period]],{{refn|group=note|The early Buddhist texts are also generally believed to be of oral tradition, with the first Pali Canon written many centuries after the death of the Buddha.<ref>{{cite journal|author=Donald S. Lopez Jr. |year=1995|title= Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna|journal= Numen|volume= 42 |number= 1 |pages= 21–47 |jstor= 3270278|doi=10.1163/1568527952598800 |hdl=2027.42/43799 |url= https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/bitstream/2027.42/43799/1/11076_1995_Article_1568527952598800.pdf|hdl-access= free }}</ref>}} perhaps earliest in the [[Kanvas|Kanva]] recension of the Yajurveda about the 1st century BCE; however oral tradition of transmission remained active.<ref name="Witzel2003">{{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|p=69}}; For oral composition and oral transmission for "many hundreds of years" before being written down, see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=76}}.</ref> [[Jack Goody]] has argued for an earlier literary tradition, concluding that the Vedas bear hallmarks of a literate culture along with oral transmission,{{sfn|Wilke|Moebus|2011|p=192}}{{sfn|Goody|1987}} but Goody's views have been strongly criticised by Falk, Lopez Jr,. and Staal, though they have also found some support.{{sfn|Lopez|2016|pp=35–36}}{{sfn|Olson|Cole|2013|p=15}} | ||

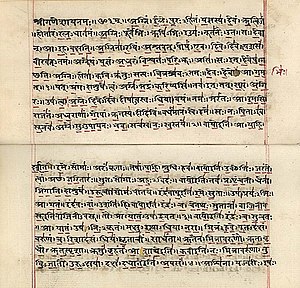

The Vedas were written down only after 500 BCE,<ref name=":0">{{Harvnb|Avari|2007|pp=69–70, 76}}</ref><ref name="Witzel2003"/>{{sfn|Wood|2007}} but only the orally transmitted texts are regarded as authoritative, given the emphasis on the exact pronunciation of the sounds.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} Witzel suggests that attempts to write down the Vedic texts towards the end of 1st millennium BCE were unsuccessful, resulting in ''smriti'' rules explicitly forbidding the writing down of the Vedas.<ref name="Witzel2003"/> Due to the ephemeral nature of the manuscript material (birch bark or palm leaves), surviving manuscripts rarely surpass an age of a few hundred years.<ref>{{Citation | last = Brodd | first = Jeffrey | title = World Religions | publisher = Saint Mary's Press | year = 2003 | location = Winona, MN | isbn = 978-0-88489-725-5 }}</ref> The [[Sampurnanand Sanskrit University]] has a Rigveda manuscript from the 14th century;<ref>{{cite book|last1=Jamison|first1=Stephanie W.|last2=Brereton|first2=Joel P.|title=The Rigveda – The Earliest Religious Poetry of India, Volume 1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fgzVAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA18 |year=2014|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-972078-1|page=18}}</ref> however, there are a number of older Veda manuscripts in [[Nepal]] that are dated from the 11th century onwards.<ref>{{cite web|title=Cultural Heritage of Nepal|url=http://www.uni-hamburg.de/ngmcp/about_ngmpp_e.html|website=Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project|publisher=[[University of Hamburg]]|access-date=4 November 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140918022828/http://www.uni-hamburg.de/ngmcp/about_ngmpp_e.html|archive-date=18 September 2014|df=dmy-all}}</ref> | The Vedas were written down only after 500 BCE,<ref name=":0">{{Harvnb|Avari|2007|pp=69–70, 76}}</ref><ref name="Witzel2003"/>{{sfn|Wood|2007}} but only the orally transmitted texts are regarded as authoritative, given the emphasis on the exact pronunciation of the sounds.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=345}} Witzel suggests that attempts to write down the Vedic texts towards the end of 1st millennium BCE were unsuccessful, resulting in ''smriti'' rules explicitly forbidding the writing down of the Vedas.<ref name="Witzel2003"/> Due to the ephemeral nature of the manuscript material (birch bark or palm leaves), surviving manuscripts rarely surpass an age of a few hundred years.<ref>{{Citation | last = Brodd | first = Jeffrey | title = World Religions | publisher = Saint Mary's Press | year = 2003 | location = Winona, MN | isbn = 978-0-88489-725-5 }}</ref> The [[Sampurnanand Sanskrit University]] has a Rigveda manuscript from the 14th century;<ref>{{cite book|last1=Jamison|first1=Stephanie W.|last2=Brereton|first2=Joel P.|title=The Rigveda – The Earliest Religious Poetry of India, Volume 1 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=fgzVAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA18 |year=2014|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-972078-1|page=18}}</ref> however, there are a number of older Veda manuscripts in [[Nepal]] that are dated from the 11th century onwards.<ref>{{cite web|title=Cultural Heritage of Nepal|url=http://www.uni-hamburg.de/ngmcp/about_ngmpp_e.html|website=Nepal-German Manuscript Preservation Project|publisher=[[University of Hamburg]]|access-date=4 November 2014|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20140918022828/http://www.uni-hamburg.de/ngmcp/about_ngmpp_e.html|archive-date=18 September 2014|df=dmy-all}}</ref> | ||

| Line 80: | Line 88: | ||

{{Main|Svādhyāya}} | {{Main|Svādhyāya}} | ||

The Vedas, Vedic rituals and its ancillary sciences called the [[ | The Vedas, Vedic rituals and its ancillary sciences called the [[Vedanga]]s, were part of the curriculum at ancient universities such as at [[Taxila]], [[Nalanda]] and [[Vikramashila]].{{sfn|Buswell|Lopez|2013}}{{sfn|Frazier|2011|page=[https://archive.org/details/continuumcompani00fraz/page/n48 34]}}<ref>{{cite book|last1=Walton|first1=Linda|title="Educational institutions" in The Cambridge World History Vol. 5 |date=2015 |publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|isbn=978-0-521-19074-9|page=122}}</ref><ref>Sukumar Dutt (1988) [1962]. ''Buddhist Monks And Monasteries of India: Their History And Contribution To Indian Culture.'' George Allen and Unwin Ltd, London. {{ISBN|81-208-0498-8}}. pp. 332–333</ref> According to Deshpande, "the tradition of the [[Sanskrit grammarians]] also contributed significantly to the preservation and interpretation of Vedic texts."{{sfn|Deshpande|1990|p=33}} [[Yāska]] (4th c. BCE{{sfn|Misra|2000|p=49}}) wrote the ''[[Nirukta]]'', which reflects the concerns about the loss of meaning of the mantras,{{refn|group=note|name="Kautas"}} while [[Pāṇini]]s (4th c. BCE) ''[[Aṣṭādhyāyī]]'' is the most important surviving text of the Vyākaraṇa traditions. [[Mimamsa]] scholar [[Sayana]]s (14th c. CE) major ''Vedartha Prakasha''{{refn|group=note|Literally, "the meaning of the Vedas made manifest."}} is a rare{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=354}} commentary on the Vedas, which is also referred to by contemporary scholars.{{sfn|Jackson|2016|loc=ch.3}} | ||

Yaska and Sayana, reflecting an ancient understanding, state that the Veda can be interpreted in three ways, giving "the truth about [[Rigvedic deities|gods]], ''[[Dharma#History|dharma]]'' and [[parabrahman]]."{{sfn|Coward|Raja|Potter|1990|p=106}}{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=34}}{{refn|group=note|Sayana repeats Yaska; see [[Nirukta#Ancient|interpretation of the Vedas]].}} The ''pūrva-kāņda'' (or ''karma-kanda''), the part of the Veda dealing with ritual, gives knowledge of ''dharma'', "which brings us satisfaction." The ''uttara-kanda'' (or ''[[Upanishads|jnana-kanda]]''),{{refn|group=note|The ''Upanishads''.{{sfn|Nakamura|1983|p=409}}}} the part of the Veda dealing with the knowledge of the absolute, gives knowledge of ''Parabrahma'', "which fulfills all of our desires."{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=30}} According to Holdrege, for the exponents of ''karma-kandha'' the Veda is to be "inscribed in the minds and hearts of men" by memorization and recitation, while for the exponents of the ''jnana-kanda'' and meditation the Vedas express a transcendental reality which can be approached with mystical means.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=355, 356–357}} | Yaska and Sayana, reflecting an ancient understanding, state that the Veda can be interpreted in three ways, giving "the truth about [[Rigvedic deities|gods]], ''[[Dharma#History|dharma]]'' and [[parabrahman]]."{{sfn|Coward|Raja|Potter|1990|p=106}}{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=34}}{{refn|group=note|Sayana repeats Yaska; see [[Nirukta#Ancient|interpretation of the Vedas]].}} The ''pūrva-kāņda'' (or ''karma-kanda''), the part of the Veda dealing with ritual, gives knowledge of ''dharma'', "which brings us satisfaction." The ''uttara-kanda'' (or ''[[Upanishads|jnana-kanda]]''),{{refn|group=note|The ''Upanishads''.{{sfn|Nakamura|1983|p=409}}}} the part of the Veda dealing with the knowledge of the absolute, gives knowledge of ''Parabrahma'', "which fulfills all of our desires."{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=30}} According to Holdrege, for the exponents of ''karma-kandha'' the Veda is to be "inscribed in the minds and hearts of men" by memorization and recitation, while for the exponents of the ''jnana-kanda'' and meditation the Vedas express a transcendental reality which can be approached with mystical means.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|pp=355, 356–357}} | ||

| Line 86: | Line 94: | ||

Holdrege notes that in Vedic learning "priority has been given to recitation over interpretation" of the Samhitas.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=354}} Galewicz states that Sayana, a [[Mimamsa]] scholar,{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=40}}{{sfn|Galewicz|2011|p=338}}{{sfn|Collins|2009|loc="237 Sayana"}} "thinks of the Veda as something to be trained and mastered to be put into practical ritual use," noticing that "it is not the meaning of the mantras that is most essential [...] but rather the perfect mastering of their sound form."{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=41}} According to Galewicz, Sayana saw the purpose (''artha'') of the Veda as the "''[[artha]]'' of carrying out sacrifice," giving precedence to the ''Yajurveda''.{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=40}} For Sayana, whether the mantras had meaning depended on the context of their practical usage.{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=41}} This conception of the Veda, as a repertoire to be mastered and performed, takes precedence over the internal meaning or "autonomous message of the hymns."{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|pp=41–42}} Most [[Śrauta#Contemporary practices|Śrauta rituals]] are not performed in the modern era, and those that are, are rare.{{sfn|Michaels|2016|pp=237–238}} | Holdrege notes that in Vedic learning "priority has been given to recitation over interpretation" of the Samhitas.{{sfn|Holdrege|1996|p=354}} Galewicz states that Sayana, a [[Mimamsa]] scholar,{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=40}}{{sfn|Galewicz|2011|p=338}}{{sfn|Collins|2009|loc="237 Sayana"}} "thinks of the Veda as something to be trained and mastered to be put into practical ritual use," noticing that "it is not the meaning of the mantras that is most essential [...] but rather the perfect mastering of their sound form."{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=41}} According to Galewicz, Sayana saw the purpose (''artha'') of the Veda as the "''[[artha]]'' of carrying out sacrifice," giving precedence to the ''Yajurveda''.{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=40}} For Sayana, whether the mantras had meaning depended on the context of their practical usage.{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|p=41}} This conception of the Veda, as a repertoire to be mastered and performed, takes precedence over the internal meaning or "autonomous message of the hymns."{{sfn|Galewicz|2004|pp=41–42}} Most [[Śrauta#Contemporary practices|Śrauta rituals]] are not performed in the modern era, and those that are, are rare.{{sfn|Michaels|2016|pp=237–238}} | ||

[[Radha Kumud Mukherjee| | [[Radha Kumud Mukherjee|Mukherjee]] notes that the Rigveda, and Sayana's commentary, contain passages criticizing as fruitless mere recitation of the ''Ŗik'' (words) without understanding their inner meaning or essence, the knowledge of ''dharma'' and ''Parabrahman''.{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|pp=29–31}} Mukherjee concludes that in the Rigvedic education of the mantras "the contemplation and comprehension of [[Nirukta|their meaning]] was considered as more important and vital to education than their mere mechanical repetition and correct pronunciation."{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|pp=29, 34}} Mookei refers to Sayana as stating that "the mastery of texts, ''akshara-praptī'', is followed by ''[[artha]]-[[Buddhi|bodha]]'', perception of their meaning."{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=35}}{{refn|group=note|name="artha"|''Artha'' may also mean "goal, purpose or essence," depending on the context.<ref>See: | ||

<br/>{{*}} [http://spokensanskrit.de/index.php?tinput=artha&direction=SE&script=HK&link=yes&beginning=0 Sanskrit English Dictionary] University of Kloen, Germany (2009) | <br />{{*}} [http://spokensanskrit.de/index.php?tinput=artha&direction=SE&script=HK&link=yes&beginning=0 Sanskrit English Dictionary] University of Kloen, Germany (2009) | ||

<br/>{{*}} Karl Potter (1998), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, {{ISBN|81-208-0310-8}}, Motilal Banarsidass, pp 610 (note 17)</ref>}} | <br />{{*}} Karl Potter (1998), Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies, Volume 4, {{ISBN|81-208-0310-8}}, Motilal Banarsidass, pp 610 (note 17)</ref>}} Mukherjee explains that the Vedic knowledge was first perceived by the ''rishis'' and ''munis''. Only the perfect language of the Vedas, as in contrast to ordinary speech, can reveal these truths, which were preserved by committing them to memory.{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|pp=34–35}} According to Mukherjee, while these truths are imparted to the student by the memorized texts,{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|pp=35–36}} "the realization of [[rta|Truth]]" and the knowledge of ''[[paramatman]]'' as revealed to the ''rishis'' is the real aim of Vedic learning, and not the mere recitation of texts.{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=36}} The supreme knowledge of the Absolute, ''[[para Brahman]]-[[Jnana yoga|jnana]]'', the knowledge of ''[[rta]]'' and ''[[satya]]'', can be obtained by taking vows of silence and obedience{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=196}} sense-restraint, ''[[Dhyana in Hinduism|dhyana]]'', the practice of ''[[Tapas (Indian religions)|tapas]]'' (austerities),{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=34}} and discussing the [[Vedanta]].{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=196}}{{refn|group=note|Mookerji also refers to the Uśanā smriti (81-2), which "states that mastery of mere text of Veda is to be followed up by its meaning" by discussing the Vedanta.{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=196}} where-after they were able to engage in doscourses on the Vedas.{{sfn|Mookerji|2011|p=29}}{{sfn|Frazier|2011|p=34}}}} | ||

==Vedic schools or recensions== | ==Vedic schools or recensions== | ||

{{Main article|Shakha}} | {{Main article|Shakha}} | ||

The four Vedas were transmitted in various [[Shakha|{{IAST|śākhā}}]]s (branches, schools).<ref name="Flood 1996 39">{{Harvnb|Flood|1996|p=39}}.</ref><ref name=witzelthreefour/> Each school likely represented an ancient community of a particular area, or kingdom.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> Each school followed its own canon. Multiple recensions are known for each of the Vedas.<ref name="Flood 1996 39"/> Thus, states Witzel as well as Renou, in the 2nd millennium BCE, there was likely no canon of one broadly accepted Vedic texts, no Vedic “Scripture”, but only a canon of various texts accepted by each school. Some of these texts have survived, most lost or yet to be found. Rigveda that survives in modern times, for example, is in only one extremely well preserved school of Śåkalya, from a region called [[Videha]], in modern north [[Bihar]], south of [[Nepal]].<ref name=jamisonwitzelvedic>Jamison and Witzel (1992), [http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/vedica.pdf Vedic Hinduism], Harvard University, p. 6</ref> The Vedic canon in its entirety consists of texts from all the various Vedic schools taken together.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> | The four Vedas were transmitted in various [[Shakha|{{IAST|śākhā}}]]s (branches, schools).<ref name="Flood 1996 39">{{Harvnb|Flood|1996|p=39}}.</ref><ref name=witzelthreefour/> Each school likely represented an ancient community of a particular area, or kingdom.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> Each school followed its own canon. Multiple recensions are known for each of the Vedas.<ref name="Flood 1996 39"/> Thus, states Witzel as well as Renou, in the 2nd millennium BCE, there was likely no canon of one broadly accepted Vedic texts, no Vedic “Scripture”, but only a canon of various texts accepted by each school. Some of these texts have survived, most lost or yet to be found. Rigveda that survives in modern times, for example, is in only one extremely well preserved school of Śåkalya, from a region called [[Videha]], in modern north [[Bihar]], south of [[Nepal]].<ref name=jamisonwitzelvedic>Jamison and Witzel (1992), [http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/vedica.pdf Vedic Hinduism], Harvard University, p. 6</ref> The Vedic canon in its entirety consists of texts from all the various Vedic schools taken together.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> | ||

There were Vedic schools that believed in [[polytheism]] in which numerous gods had different natural functions, [[Henotheism|henotheistic]] beliefs where only one god was worshipped but others were thought to exist, [[Monotheism|monotheistic]] beliefs in a single [[god]], [[agnosticism]], and [[Monism|monistic]] beliefs where "there is an absolute reality that goes beyond the gods and that includes or transcends everything that exists."<ref name=":102">{{Cite book |last=Stevenson |first=Jay |title=The Complete Idiot's Guide to Eastern Philosophy |publisher=[[Alpha Books]] |year=2000 |isbn=9780028638201 |location=Indianapolis |pages=46 |language=en-US}}</ref> [[Indra]], [[Agni]], and [[Yama]] were popular subjects of worship by polytheist organizations.<ref name=":102" /> | |||

Each of the four Vedas were shared by the numerous schools, but revised, interpolated and adapted locally, in and after the Vedic period, giving rise to various recensions of the text. Some texts were revised into the modern era, raising significant debate on parts of the text which are believed to have been corrupted at a later date.<ref>J. Muir (1872), {{Google books|HRYAAAAAYAAJ|Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, their religion and institutions, Vol. 1}}, 2nd Edition, p. 12</ref><ref>Albert Friedrich Weber, {{Google books|Bi8JAAAAQAAJ|Indische Studien, herausg. von}}, Vol. 10, pp. 1–9 with footnotes (in German); For a translation, {{Google books|HRYAAAAAYAAJ|Original Sanskrit Texts}}, p. 14</ref> The Vedas each have an Index or [[Anukramaṇī|Anukramani]], the principal work of this kind being the general Index or ''{{IAST|Sarvānukramaṇī}}''.<ref>For an example, see [http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/3178027 Sarvānukramaṇī Vivaraṇa] Univ of Pennsylvania rare texts collection</ref><ref>R̥gveda-sarvānukramaṇī Śaunakakr̥tāʼnuvākānukramaṇī ca, Maharṣi-Kātyayāna-viracitā, {{oclc|11549595}}</ref> | Each of the four Vedas were shared by the numerous schools, but revised, interpolated and adapted locally, in and after the Vedic period, giving rise to various recensions of the text. Some texts were revised into the modern era, raising significant debate on parts of the text which are believed to have been corrupted at a later date.<ref>J. Muir (1872), {{Google books|HRYAAAAAYAAJ|Original Sanskrit Texts on the Origin and History of the People of India, their religion and institutions, Vol. 1}}, 2nd Edition, p. 12</ref><ref>Albert Friedrich Weber, {{Google books|Bi8JAAAAQAAJ|Indische Studien, herausg. von}}, Vol. 10, pp. 1–9 with footnotes (in German); For a translation, {{Google books|HRYAAAAAYAAJ|Original Sanskrit Texts}}, p. 14</ref> The Vedas each have an Index or [[Anukramaṇī|Anukramani]], the principal work of this kind being the general Index or ''{{IAST|Sarvānukramaṇī}}''.<ref>For an example, see [http://hdl.library.upenn.edu/1017/d/medren/3178027 Sarvānukramaṇī Vivaraṇa] Univ of Pennsylvania rare texts collection</ref><ref>R̥gveda-sarvānukramaṇī Śaunakakr̥tāʼnuvākānukramaṇī ca, Maharṣi-Kātyayāna-viracitā, {{oclc|11549595}}</ref> | ||

| Line 98: | Line 108: | ||

Prodigious energy was expended by ancient Indian culture in ensuring that these texts were transmitted from generation to generation with inordinate fidelity.<ref name=":1">{{Harvnb|Staal|1986}}</ref> For example, memorization of the sacred ''Vedas'' included up to eleven [[Vedic chant|forms of recitation]] of the same text. The texts were subsequently "proof-read" by comparing the different recited versions. Forms of recitation included the ''{{IAST|jaṭā-pāṭha}}'' (literally "mesh recitation") in which every two adjacent words in the text were first recited in their original order, then repeated in the reverse order, and finally repeated in the original order.<ref name=filliozat-p139>{{Harvnb|Filliozat|2004|p=139}}</ref> That these methods have been effective, is attested to by the preservation of the most ancient Indian religious text, the ''[[Rigveda]]'', as [[Redaction|redacted]] into a single text during the ''Brahmana'' period, without any variant readings within that school.<ref name=filliozat-p139/> | Prodigious energy was expended by ancient Indian culture in ensuring that these texts were transmitted from generation to generation with inordinate fidelity.<ref name=":1">{{Harvnb|Staal|1986}}</ref> For example, memorization of the sacred ''Vedas'' included up to eleven [[Vedic chant|forms of recitation]] of the same text. The texts were subsequently "proof-read" by comparing the different recited versions. Forms of recitation included the ''{{IAST|jaṭā-pāṭha}}'' (literally "mesh recitation") in which every two adjacent words in the text were first recited in their original order, then repeated in the reverse order, and finally repeated in the original order.<ref name=filliozat-p139>{{Harvnb|Filliozat|2004|p=139}}</ref> That these methods have been effective, is attested to by the preservation of the most ancient Indian religious text, the ''[[Rigveda]]'', as [[Redaction|redacted]] into a single text during the ''Brahmana'' period, without any variant readings within that school.<ref name=filliozat-p139/> | ||

The Vedas were orally transmitted by memorization | The Vedas were orally transmitted by memorization, and were written down only after 500 BCE,<ref name=":0"/><ref name="Witzel2003"/>{{sfn|Wood|2007}} All printed editions of the Vedas that survive in the modern times are likely the version existing in about the 16th century CE.<ref>{{Harvnb|Witzel|2003|p=69}}, "... almost all printed editions depend on the late manuscripts that are hardly older than 500 years"</ref> | ||

==Four Vedas== | ==Four Vedas== | ||

{{Vedas and Shakhas}} | {{Vedas and Shakhas}} | ||

| Line 108: | Line 117: | ||

# [[Atharvaveda]] (AV) | # [[Atharvaveda]] (AV) | ||

Of these, the first three were the principal original division, also called "''{{IAST|trayī vidyā}}''"; that is, "the triple science" of reciting hymns (Rigveda), performing sacrifices (Yajurveda), and chanting songs (Samaveda).<ref>Witzel, M., "[http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/canon.pdf The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools : The Social and Political Milieu]" in {{Harvnb|Witzel|1997|pp=257–348}}</ref>{{sfn|MacDonell|2004|pp=29–39}} The Rig Veda most likely was composed between {{circa}} 1500 and 1200.{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}} Witzel notes that it is the Vedic period itself, where incipient lists divide the Vedic texts into three (trayī) or four branches: Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> | Of these, the first three were the principal original division, also called "''{{IAST|trayī vidyā}}''"; that is, "the triple science" of reciting hymns (Rigveda), performing sacrifices (Yajurveda), and chanting songs (Samaveda).<ref>Witzel, M., "[http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/canon.pdf The Development of the Vedic Canon and its Schools : The Social and Political Milieu]" in {{Harvnb|Witzel|1997|pp=257–348}}</ref>{{sfn|MacDonell|2004|pp=29–39}} The Rig Veda most likely was composed between {{circa}} 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE.{{refn|group=note|name="dating"}} Witzel notes that it is the Vedic period itself, where incipient lists divide the Vedic texts into three (trayī) or four branches: Rig, Yajur, Sama and Atharva.<ref name=witzelthreefour/> | ||

Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the [[Samhita]]s (mantras and benedictions), the [[Aranyakas]] (text on rituals, ceremonies such as newborn baby's rites of passage, coming of age, marriages, retirement and cremation, sacrifices and symbolic sacrifices), the [[Brahmanas]] (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the [[Upanishads]] (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).<ref name="gflood"/><ref name="A Bhattacharya 2006 pp. 8–14"/><ref name="Jan Gonda 1975"/> The [[Upasana]]s (short ritual worship-related sections) are considered by some scholars{{sfn|Bhattacharya|2006|pp=8–14}}{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|pp=351–357}} as the fifth part. [[Michael Witzel|Witzel]] notes that the rituals, rites and ceremonies described in these ancient texts reconstruct to a large degree the Indo-European marriage rituals observed in a region spanning the Indian subcontinent, Persia and the European area, and some greater details are found in the Vedic era texts such as the Grhya Sūtras.<ref>Jamison and Witzel (1992), [http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/vedica.pdf Vedic Hinduism], Harvard University, p. 21</ref> | Each Veda has been subclassified into four major text types – the [[Samhita]]s (mantras and benedictions), the [[Aranyakas]] (text on rituals, ceremonies such as newborn baby's rites of passage, coming of age, marriages, retirement and cremation, sacrifices and symbolic sacrifices), the [[Brahmanas]] (commentaries on rituals, ceremonies and sacrifices), and the [[Upanishads]] (text discussing meditation, philosophy and spiritual knowledge).<ref name="gflood"/><ref name="A Bhattacharya 2006 pp. 8–14"/><ref name="Jan Gonda 1975"/> The [[Upasana]]s (short ritual worship-related sections) are considered by some scholars{{sfn|Bhattacharya|2006|pp=8–14}}{{sfn|Holdrege|1995|pp=351–357}} as the fifth part. [[Michael Witzel|Witzel]] notes that the rituals, rites and ceremonies described in these ancient texts reconstruct to a large degree the Indo-European marriage rituals observed in a region spanning the Indian subcontinent, Persia and the European area, and some greater details are found in the Vedic era texts such as the Grhya Sūtras.<ref>Jamison and Witzel (1992), [http://www.people.fas.harvard.edu/~witzel/vedica.pdf Vedic Hinduism], Harvard University, p. 21</ref> | ||

| Line 121: | Line 130: | ||

|quote=[[Nasadiya Sukta]] (Hymn of non-Eternity): | |quote=[[Nasadiya Sukta]] (Hymn of non-Eternity): | ||

Who really knows?<br> | Who really knows?<br /> | ||

Who can here proclaim it?<br> | Who can here proclaim it?<br /> | ||

Whence, whence this creation sprang?<br> | Whence, whence this creation sprang?<br /> | ||

Gods came later, after the creation of this universe. | Gods came later, after the creation of this universe. | ||

Who then knows whence it has arisen?<br> | Who then knows whence it has arisen?<br /> | ||

Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;<br> | Whether God's will created it, or whether He was mute;<br /> | ||

Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,<br> | Only He who is its overseer in highest heaven knows,<br /> | ||

He only knows, or perhaps He does not know. | He only knows, or perhaps He does not know. | ||

|source =—[[Rig Veda]] 10.129.6–7<ref name=nasadiyasukta> | |source =—[[Rig Veda]] 10.129.6–7<ref name=nasadiyasukta> | ||

Original Sanskrit: [https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_१०.१२९ Rigveda 10.129] Wikisource; | Original Sanskrit: [https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/ऋग्वेद:_सूक्तं_१०.१२९ Rigveda 10.129] Wikisource; | ||

<br/>{{*}}Translation 1: {{cite book|author=Max Müller|title=A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature|date=1859|publisher=Williams and Norgate, London|url=https://archive.org/stream/historyofancient00mluoft#page/564/mode/2up|pages=559–565|author-link=Max Müller}} | <br />{{*}}Translation 1: {{cite book|author=Max Müller|title=A History of Ancient Sanskrit Literature|date=1859|publisher=Williams and Norgate, London|url=https://archive.org/stream/historyofancient00mluoft#page/564/mode/2up|pages=559–565|author-link=Max Müller}} | ||

<br/>{{*}}Translation 2: {{cite book|author=Kenneth Kramer|title=World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions|date=1986|publisher=Paulist Press|isbn=978-0-8091-2781-8|page=21}} | <br />{{*}}Translation 2: {{cite book|author=Kenneth Kramer|title=World Scriptures: An Introduction to Comparative Religions|date=1986|publisher=Paulist Press|isbn=978-0-8091-2781-8|page=21}} | ||

<br/>{{*}}Translation 3: {{cite book|author=David Christian|title=Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History|url=https://archive.org/details/mapstimeintroduc00chri_515|url-access=limited|date=2011|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-95067-2|pages=[https://archive.org/details/mapstimeintroduc00chri_515/page/n45 17]–18}}</ref>}} | <br />{{*}}Translation 3: {{cite book|author=David Christian|title=Maps of Time: An Introduction to Big History|url=https://archive.org/details/mapstimeintroduc00chri_515|url-access=limited|date=2011|publisher=University of California Press|isbn=978-0-520-95067-2|pages=[https://archive.org/details/mapstimeintroduc00chri_515/page/n45 17]–18}}</ref>}} | ||

The [[Rigveda|Rigveda Samhita]] is the oldest extant [[Indo-Aryan languages|Indic]] text.<ref>see e.g. {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> It is a collection of 1,028 [[Vedic Sanskrit]] [[hymn]]s and 10,600 verses in all, organized into ten books (Sanskrit: ''mandalas'').<ref>For 1,028 hymns and 10,600 verses and division into ten mandalas, see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> The hymns are dedicated to [[Rigvedic deities]].<ref>For characterization of content and mentions of deities including Agni, Indra, Varuna, Soma, Surya, etc. see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> | The [[Rigveda|Rigveda Samhita]] is the oldest extant [[Indo-Aryan languages|Indic]] text.<ref>see e.g. {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> It is a collection of 1,028 [[Vedic Sanskrit]] [[hymn]]s and 10,600 verses in all, organized into ten books (Sanskrit: ''mandalas'').<ref>For 1,028 hymns and 10,600 verses and division into ten mandalas, see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> The hymns are dedicated to [[Rigvedic deities]].<ref>For characterization of content and mentions of deities including Agni, Indra, Varuna, Soma, Surya, etc. see: {{Harvnb|Avari|2007|p=77}}.</ref> | ||