Bhagavad Gita

Thank you for being part of the Bharatpedia family! 0% transparency: ₹0 raised out of ₹100,000 (0 supporter) |

| Bhagavad Gita | |

|---|---|

| |

| Information | |

| Religion | Hinduism |

| Author | Traditionally attributed to Vyasa |

| Language | Sanskrit |

| Period | 1st-millennium BCE |

| Chapters | 18 |

| Sutras | Yoga Sutras |

| Verses | 700 (approx.) |

| Part of a series on |

| Vaishnavism |

|---|

|

|

|

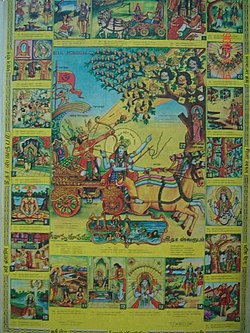

The Shrimad Bhagavad Gita (/ˌbʌɡəvəd ˈɡiːtɑː, -tə/; Sanskrit: श्रीमद्भगवद्गीता, lit. 'The Song by God';[lower-alpha 1] IAST: bhagavadgītā),[1] often referred to as the Gita (IAST: gītā), is a 700-verse Hindu scripture that is part of the epic Mahabharata (chapters 23–40 of Bhishma Parva), dated to the second half of the first millennium BCE and exemplary for the emerging Hindu synthesis. It is considered to be one of the holy scriptures for Hinduism.

The Gita is set in a narrative framework of a dialogue between Pandava prince Arjuna and his guide and charioteer Krishna, an avatar of Lord Vishnu. At the start of the Dharma Yuddha (righteous war) between Pandavas and Kauravas, Arjuna is filled with moral dilemma and despair about the violence and death the war will cause in the battle against his own kin.[2] He wonders if he should renounce and seeks Krishna's counsel, whose answers and discourse constitute the Bhagavad Gita. Krishna counsels Arjuna to "fulfill his Kshatriya (warrior) duty to uphold the Dharma" through "selfless action".[web 1][3][note 1] The Krishna–Arjuna dialogues cover a broad range of spiritual topics, touching upon ethical dilemmas and philosophical issues that go far beyond the war Arjuna faces.[1][4][5]

Numerous commentaries have been written on the Bhagavad Gita with widely differing views on the essentials. According to some, Bhagavad Gita is written by the god Ganesha which was told to him by Vyasa. Vedanta commentators read varying relations between Self and Brahman in the text: Advaita Vedanta sees the non-dualism of Atman (soul) and Brahman (universal soul) as its essence,[6] whereas Bhedabheda and Vishishtadvaita see Atman and Brahman as both different and non-different, while Dvaita Vedanta sees dualism of Atman (soul) and Brahman as its essence. The setting of the Gita in a battlefield has been interpreted as an allegory for the ethical and moral struggles of human life.[5][7][8]

The Bhagavad Gita presents a synthesis[9][10] of Hindu ideas about dharma,[9][10][11] theistic bhakti,[11][12] and the yogic ideals[10] of moksha.[10] The text covers jñāna, bhakti, karma, and rāj yogas (spoken of in the 6th chapter)[12] incorporating ideas from the Samkhya-Yoga philosophy.[web 1][note 2]

The Bhagavad Gita is the best known and most famous of Hindu texts,[13] with a unique pan-Hindu influence.[14][15] The Gita's call for selfless action inspired many leaders of the Indian independence movement including Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi; the latter referred to it as his "spiritual dictionary".[16]

| Part of a series on |

| Hindu scriptures and texts |

|---|

|

| Related Hindu texts |

Nomenclature

The Gita in the title of the Bhagavad Gita means "song". Religious leaders and scholars interpret the word Bhagavad in a number of ways. Accordingly, the title has been interpreted as "the word of God" by the theistic schools,[17] "the words of the Lord",[18] "the Divine Song",[19][20] and "Celestial Song" by others.[21] In India, its Sanskrit name is often written as Shrimad Bhagavad Gita, श्रीमद् भगवद् गीता (the latter two words often written as a single word भगवद्गीता), where the Shrimad prefix is used to denote a high degree of respect. This is not to be confused with the Shrimad Bhagavatam, which is a Purana dealing with the life of the Hindu God Krishna and various avatars of Vishnu.

The work is also known as the Iswara Gita, the Ananta Gita, the Hari Gita, the Vyasa Gita, or simply the Gita.[22]

Authorship

In the Indian tradition, the Bhagavad Gita, as well as the epic Mahabharata of which it is a part, is attributed to the sage Vyasa,[23] whose full name was Krishna Dvaipayana, also called Veda-Vyasa.[24] Another Hindu legend states that Vyasa narrated it while the elephant-headed deity Ganesha broke one of his tusks and wrote down the Mahabharata along with the Bhagavad Gita.[25][26][note 3]

Scholars consider Vyasa to be a mythical or symbolic author, in part because Vyasa is also the traditional compiler of the Vedas and the Puranas, texts dated to be from different millennia.[25][29][30] The word Vyasa literally means "arranger, compiler", and is a surname in India. According to Kashi Nath Upadhyaya, a Gita scholar, it is possible that a number of different individuals with the same name compiled different texts.[31]

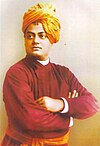

Swami Vivekananda, the 19th-century Hindu monk and Vedantist, stated that the Bhagavad Gita may be old but it was mostly unknown in the Indian history till early 8th century when Adi Shankara (Shankaracharya) made it famous by writing his much-followed commentary on it.[32][33] Some infer, states Vivekananda, that "Shankaracharya was the author of Gita, and that it was he who foisted it into the body of the Mahabharata."[32] This attribution to Adi Shankara is unlikely in part because Shankara himself refers to the earlier commentaries on the Bhagavad Gita, and because other Hindu texts and traditions that compete with the ideas of Shankara refer to much older literature referencing the Bhagavad Gita, though much of this ancient secondary literature has not survived into the modern era.[32]

According to J. A. B. van Buitenen, an Indologist known for his translations and scholarship on Mahabharata, the Gita is so contextually and philosophically well knit with the Mahabharata that it was not an independent text that "somehow wandered into the epic".[34] The Gita, states van Buitenen, was conceived and developed by the Mahabharata authors to "bring to a climax and solution the dharmic dilemma of a war".[34][note 4]

According to Alexus McLeod, a scholar of Philosophy and Asian Studies, it is "impossible to link the Bhagavad Gita to a single author", and it may be the work of many authors.[25][37] This view is shared by the Indologist Arthur Basham, who states that there were three or more authors or compilers of Bhagavad Gita. This is evidenced by the discontinuous intermixing of philosophical verses with theistic or passionately theistic verses, according to Basham.[38][note 5]

Date

Theories on the date of the composition of the Gita vary considerably. Some scholars accept dates from the fifth century to the second century BCE as the probable range, the latter likely. The Hinduism scholar Jeaneane Fowler, in her commentary on the Gita, considers second century BCE to be the probable date of composition. [39] J. A. B. van Buitenen too states that the Gita was likely composed about 200 BCE.[40] According to the Indologist Arvind Sharma, the Gita is generally accepted to be a 2nd-century-BCE text.[41]

Kashi Nath Upadhyaya, in contrast, dates it a bit earlier. He states that the Gita was always a part of the Mahabharata, and dating the latter suffices in dating the Gita.[42] On the basis of the estimated dates of Mahabharata as evidenced by exact quotes of it in the Buddhist literature by Asvaghosa (c. 100 CE), Upadhyaya states that the Mahabharata, and therefore Gita, must have been well known by then for a Buddhist to be quoting it.[42][note 6] This suggests a terminus ante quem (latest date) of the Gita to be sometime prior to the 1st century CE.[42] He cites similar quotes in the Dharmasutra texts, the Brahma sutras, and other literature to conclude that the Bhagavad Gita was composed in the fifth or fourth century BCE.[44][note 7]

According to Arthur Basham, the context of the Bhagavad Gita suggests that it was composed in an era when the ethics of war were being questioned and renunciation to monastic life was becoming popular.[46] Such an era emerged after the rise of Buddhism and Jainism in the 5th century BCE, and particularly after the semi-legendary life of Ashoka in 3rd century BCE. Thus, the first version of the Bhagavad Gita may have been composed in or after the 3rd century BCE.[46]

Linguistically, the Bhagavad Gita is in classical Sanskrit of the early variety, states the Gita scholar Winthrop Sargeant.[47] The text has occasional pre-classical elements of the Sanskrit language, such as the aorist and the prohibitive mā instead of the expected na (not) of classical Sanskrit.[47] This suggests that the text was composed after the Pāṇini era, but before the long compounds of classical Sanskrit became the norm. This would date the text as transmitted by the oral tradition to the later centuries of the 1st-millennium BCE, and the first written version probably to the 2nd or 3rd century CE.[47][48]

According to Jeaneane Fowler, "the dating of the Gita varies considerably" and depends in part on whether one accepts it to be a part of the early versions of the Mahabharata, or a text that was inserted into the epic at a later date.[49] The earliest "surviving" components therefore are believed to be no older than the earliest "external" references we have to the Mahabharata epic. The Mahabharata – the world's longest poem – is itself a text that was likely written and compiled over several hundred years, one dated between "400 BCE or little earlier, and 2nd century CE, though some claim a few parts can be put as late as 400 CE", states Fowler. The dating of the Gita is thus dependent on the uncertain dating of the Mahabharata. The actual dates of composition of the Gita remain unresolved.[49] While the year and century is uncertain, states Richard Davis,[50] the internal evidence in the text dates the origin of the Gita discourse to the Hindu lunar month of Margashirsha (also called Agrahayana, generally December or January of the Gregorian calendar).[51]

Composition and significance

The Bhagavad Gita is the best known,[52] and most influential of Hindu scriptures.[13] While Hinduism is known for its diversity and its synthesis therefrom, the Bhagavad Gita has a unique pan-Hindu influence.[14][53] Gerald James Larson – an Indologist and classical Hindu Philosophies scholar, states "if there is any one text that comes near to embodying the totality of what it is to be a Hindu, it would be the Bhagavad Gita."[13][15]

The Bhagavad Gita is part of the Prasthanatrayi, which also includes the Upanishads and Brahma sutras. These are the three starting points for the Vedanta school of Hindu philosophy.[54] The Brahma sutras constitute the Nyāya prasthāna or the "starting point of reasoning canonical base", while the principal Upanishads constitute the Sruti prasthāna or the "starting point of heard scriptures", and the Bhagavad Gita constitutes the Smriti prasthāna or the "starting point of remembered canonical base".[54] The Bhagavad Gita is a "summation of the Vedanta", states Sargeant.[55] It is thus one of the key texts for the Vedanta,[56][57] a school that provides one of the theoretical foundations for Hinduism,[58] and one that has had an enormous influence over time, becoming the central ideology of the Hindu renaissance in the 19th century, according to Gavin Flood – a scholar of Hinduism.[59]

Some Hindus give it the status of an Upanishad, and some consider it to be a "revealed text".[60][61][62] Others consider the Bhagavad Gita as an important Smriti,[63] or secondary text that exist in alternate versions such as one found in Kashmir though it does not affect the basic message of the text.[64][65][66]

Hindu synthesis

The Bhagavad Gita is the sealing achievement of the Hindu synthesis, incorporating its various religious traditions.[10][11][12] The synthesis is at both philosophical and socio-religious levels, states the Gita scholar Keya Maitra.[67] The text refrains from insisting on one right marg (path) to spirituality. It openly synthesizes and inclusively accepts multiple ways of life, harmonizing spiritual pursuits through action (karma), knowledge (gyaana), and devotion (bhakti).[68] According to the Gita translator Radhakrishnan, quoted in a review by Robinson, Krishna's discourse is a "comprehensive synthesis" that inclusively unifies the competing strands of Hindu thought such as "Vedic ritual, Upanishadic wisdom, devotional theism and philosophical insight".[69] Aurobindo described the text as a synthesis of various Yogas. The Indologist Robert Minor, and others,[web 1] in contrast, state the Gita is "more clearly defined as a synthesis of Vedanta, Yoga and Samkhya" philosophies of Hinduism.[70]

The synthesis in Bhagavad Gita addresses the question as to what constitutes the virtuous path and one necessary for the spiritual liberation and a release from the cycles of rebirth (moksha).[71][72] It discusses whether one should renounce a householder lifestyle for a life as an ascetic, or lead a householder life dedicated to one's duty and profession, or pursue a householder life devoted to a personalized god in the revealed form of Krishna. Thus Gita discusses and synthesizes the three dominant trends in Hinduism: enlightenment-based renunciation, dharma-based householder life, and devotion-based theism. According to Deutsch and Dalvi, the Bhagavad Gita attempts "to forge a harmony" between these three paths.[12][note 8]

The Bhagavad Gita's synthetic answer recommends that one must resist the "either-or" view, and consider a "both-and" view.[73][74][75] It states the dharmic householder can achieve the same goals as the renouncing monk through "inner renunciation", that is "motiveless action".[71][note 9] One must do the right thing because one has determined that it is right, states Gita, without craving for its fruits, without worrying about the results, loss or gain.[77][78][79] Desires, selfishness and the craving for fruits can distort one from the dharmic action and spiritual living.[78] The Gita synthesis goes further, according to its interpreters such as Swami Vivekananda, and the text states that there is Living God in every human being and the devoted service to this Living God in everyone – without craving for personal rewards – is a means to spiritual development and liberation.[80][81][82] According to Galvin Flood, the teachings in Gita differ from other Indian religions that encouraged extreme austerity and self-torture of various forms (karsayanta). The Gita disapproves of these, stating that not only is it against the tradition but against Krishna himself, because "Krishna dwells within all beings, in torturing the body the ascetic would be torturing him", states Flood. Even a monk should strive for the "inner renunciation", rather than external pretensions.[83]

The Gita synthesizes several paths to spiritual realization based on the premise that people are born with different temperaments and tendencies (guna).[84] According to Winthrop Sargeant, the text acknowledges that some individuals are more reflective and intellectual, some affective and engaged by their emotions, some are action driven, yet others favor experimenting and exploring what works.[84] It then presents different spiritual paths for each personality type respectively: the path of knowledge (jnana yoga), the path of devotion (bhakti yoga), the path of action (karma yoga), and the path of meditation (raja yoga).[84][85] The guna premise is a synthesis of the ideas from the Samkhya school of Hinduism. According to Upadhyaya, the Gita states that none of these paths to spiritual realization are "intrinsically superior or inferior", rather they "converge in one and lead to the same goal".[86]

According to Hiltebeitel, Bhakti forms an essential ingredient of this synthesis, and the text incorporates Bhakti into Vedanta.[87] According to Scheepers, The Bhagavad Gita is a Brahmanical text which uses the shramanic and Yogic terminology to spread the Brahmanic idea of living according to one's duty or dharma, in contrast to the ascetic ideal of liberation by avoiding all karma.[88] According to Galvin Flood and Charles Martin, the Gita rejects the shramanic path of non-action, emphasizing instead "the renunciation of the fruits of action".[89] The Bhagavad Gita, states Raju, is a great synthesis of the ideas of the impersonal spiritual monism with personal God, of "the yoga of action with the yoga of transcendence of action, and these again with yogas of devotion and knowledge".[11]

Manuscripts

The Bhagavad Gita manuscript is found in the sixth book of the Mahabharata manuscripts – the Bhisma-parvan. Therein, in the third section, the Gita forms chapters 23–40, that is 6.3.23 to 6.3.40.[90] The Bhagavad Gita is often preserved and studied on its own, as an independent text with its chapters renumbered from 1 to 18.[90]

The Bhagavad Gita manuscripts exist in numerous Indic scripts.[91] These include writing systems that are currently in use, as well as early scripts such as the Sharada script, now dormant.[91][92] Variant manuscripts of the Gita have been found on the Indian subcontinent[64][93] Unlike the enormous variations in the remaining sections of the surviving Mahabharata manuscripts, the Gita manuscripts show only minor variations and the meaning is the same.[64][93]

According to Gambhirananda, the old manuscripts may have had 745 verses, though he agrees that 700 verses is the generally accepted historic standard.[94] Gambhirananda's view is supported by a few versions of chapter 6.43 of the Mahabharata. These versions state the Gita is a text where "Kesava [Krishna] spoke 620 slokas, Arjuna 57, Samjaya 67, and Dhritarashtra 1", states the Religious Studies and Gita exegesis scholar Robert Minor.[95] This adds to 745 verses. An authentic manuscript of the Gita with 745 verses has not been found.[96] Of all known extant historic manuscripts, the largest version contains 715 verses.[95] Adi Shankara, in his 8th-century commentary, explicitly states that the Gita has 700 verses, which was likely a deliberate declaration to prevent further insertions and changes to the Gita. Since Shankara's time, the "700 verses" has been the standard benchmark for the critical edition of the Bhagavad Gita.[96]

Contents

Themes

Translations

The first English translation of the Bhagavad Gita was published by Charles Wilkins in 1785.[97] The Wilkins translation had an introduction to the Gita by Warren Hastings. Soon the work was translated into other European languages such as French (1787), German, and Russian. In 1849, the Weleyan Mission Press, Bangalore published The Bhagavat-Geeta, Or, Dialogues of Krishna and Arjoon in Eighteen Lectures, with Sanskrit, Canarese and English in parallel columns, edited by Rev. John Garrett, and the efforts being supported by Sir. Mark Cubbon.[98]

In 1981, Larson stated that "a complete listing of Gita translations and a related secondary bibliography would be nearly endless".[99]:514 According to Larson, there is "a massive translational tradition in English, pioneered by the British, solidly grounded philologically by the French and Germans, provided with its indigenous roots by a rich heritage of modern Indian comment and reflection, extended into various disciplinary areas by Americans, and having generated in our time a broadly based cross-cultural awareness of the importance of the Bhagavad Gita both as an expression of a specifically Indian spirituality and as one of the great religious "classics" of all time."[99]:518

According to Sargeant, the Gita is "said to have been translated at least 200 times, in both poetic and prose forms".[100] Richard Davis cites a count by Callewaert & Hemraj in 1982 of 1,891 translations of the Bhagavad Gita in 75 languages, including 273 in English.[101] These translations vary,[102] and are in part an interpretative reconstruction of the original Sanskrit text that differ in their "friendliness to the reader",[103] and in the amount of "violence to the original Gita text" that the translation does.[104][note 10]

The translations and interpretations of the Gita have been so diverse that these have been used to support apparently contradictory political and philosophical values. For example, state Galvin Flood and Charles Martin, these interpretations have been used to support "pacifism to aggressive nationalism" in politics, from "monism to theism" in philosophy.[109] According to William Johnson, the synthesis of ideas in the Gita is such that it can bear almost any shade of interpretation.[110] A translation "can never fully reproduce an original and no translation is transparent", states Richard Davis, but in the case of Gita the linguistic and cultural distance for many translators is large and steep which adds to the challenge and affects the translation.[111] For some native translators, their personal beliefs, motivations, and subjectivity affect their understanding, their choice of words and interpretation.[112][113][114] Some translations by Indians, with or without Western co-translators, have "orientalist", "apologetic", "Neo-Vedantin" or "guru phenomenon" bias.[99]:525–530

| A sample of English translations of the Bhagavad Gita[99] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Title | Translator | Year |

| The Bhagavat geeta, or Dialogue of Kreeshna and Arjoon in Eighteen Lectures with Notes | Charles Wilkins | 1785 |

| Bhagavad-Gita | August Wilhelm Schlegel | 1823 |

| The Bhagavadgita | J.C. Thomson | 1856 |

| La Bhagavad-Gita | Eugene Burnouf | 1861 |

| The Bhagavad Gita[note 11] | Kashninath T. Telang | 1882 |

| The Song Celestial[note 12] | Sir Edwin Arnold | 1885 |

| The Bhagavad Gita[note 13] | William Quan Judge | 1890 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita with the Commentary of Sri Sankaracarya | A. Mahadeva Sastry | 1897 |

| Young Men’s Gita | Jagindranath Mukharji | 1900 |

| Bhagavadgita: The Lord's Song | L.D. Barnett | 1905 |

| Bhagavad Gita[note 14] | Anne Besant and Bhagavan Das | 1905 |

| Die Bhagavadgita | Richard Garbe | 1905 |

| Srimad Bhagavad-Gita | Swami Swarupananda | 1909 |

| Der Gesang des Heiligen | Paul Deussen | 1911 |

| Srimad Bhagavad-Gita | Swami Paramananda | 1913 |

| La Bhagavad-Gîtâ | Emile Sénart | 1922 |

| The Bhagavad Gita according to Gandhi[note 15] | Mohandas K. Gandhi | 1926 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | W. Douglas P. Hill | 1928 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita | Arthur W. Ryder | 1929 |

| The Song of the Lord, Bhagavad-Gita | E.J. Thomas | 1931 |

| The Geeta | Shri Purohit Swami | 1935 |

| The Yoga of the Bhagavat Gita | Sri Krishna Prem | 1938 |

| The Message of the Gita (or Essays on the Gita) | Sri Aurobindo, edited by Anilbaran Roy | 1938 |

| Bhagavadgita[note 16] | Swami Sivananda | 1942 |

| Bhagavad Gita[note 17] | Swami Nikhilananda | 1943 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Franklin Edgerton | 1944 |

| The Song of God: Bhagavad Gita | Swami Prabhavananda and Christopher Isherwood | 1944 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Swami Nikhilananda | 1944 |

| The Bhagavadgita | S. Radhakrishnan | 1948 |

| God Talks with Arjuna | Paramhamsa Yogananda | 1955 |

| The Bhagavadgita | Shakuntala Rao Sastri | 1959 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Juan Mascaro | 1962 |

| Bhagavad Gita | C. Rajagopalachari | 1963 |

| The Bhagavadgita | Swami Chidbhavananda | 1965 |

| The Bhagavad Gita[note 18] | Maharishi Mahesh Yogi | 1967 |

| The Bhagavadgita: Translated with Introduction and Critical Essays | Eliot Deutsch | 1968 |

| Bhagavad-gita As It Is | A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada | 1968 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | R.C. Zaehner | 1969 |

| The Bhagavad Gita: A New Verse Translation | Ann Stanford | 1970 |

| The Holy Gita, Translation & Commentary | Swami Chinmayananda | 1972 |

| Srimad Bhagavad Gita | Swami Vireswarananda | 1974 |

| Bhagavad Gita: A Verse Translation[note 19] | Geoffrey Parrinder | 1974 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Kees. W. Bolle | 1979 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Winthrop Sargeant (Editor: Christopher K Chapple) | 1979 |

| The Bhagavadgita in the Mahabharata | J.A.B. van Buitenen | 1981 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita | Winthrop Sargeant | 1984 |

| Srimad Bhagavad Gita Bhasya of Sri Samkaracharya | A.G. Krishna Warrier | 1984 |

| The Bhagavadgita | Eknath Easwaran | 1985 |

| Srimad Bhagavad Gita | Swami Tapasyananda | 1985 |

| Bhagavad Gita | Srinivasa Murthy | 1985 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita: Krishna's Counsel in Time of War | Barbara Stoler Miller | 1986 |

| Bhagavad-Gita | Raghavan Iyer | 1986 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita | Ramananda Prasad | 1988 |

| Bhagavad-Gita for You & Me | M.S. Patwardhan | 1990 |

| Bhagavad Gita | Antonio T. De Nicholas | 1991 |

| Bhagavad Gita | Sachindra K. Majumdar | 1991 |

| Bhagavad Gita | O.P. Ghai | 1992 |

| Ramanuja Gita Bhashya | Swami Adidevananda | 1992 |

| Gita Bhashya | Jagannatha Prakasha | 1993 |

| Bhagavad Gita: Translation & Commentary | Richard Gotshalk | 1993 |

| The Bhagavad Gita[note 20] | P. Lal | 1994 |

| The Bhagavad-Gita | W.J. Johnson | 1994 |

| Bhagavad Gita (The Song of God) | Ramananda Prasad | 1996 |

| Bhagavad Gita[note 21] | Vrinda Nabar and Shanta Tumkur | 1997 |

| The Living Gita: The Complete Bhagavat Gita: A Commentary for Modern Readers | Swami Satchidananda | 1997 |

| Bhagavad-Gita | Satyananda Saraswati | 1997 |

| Bhagavad-Gita with the Commentary of Sankaracarya | Swami Gambhirananda | 1998 |

| Bhagavad Gita, With Commentary of Sankara | Alladi M. Sastry | 1998 |

| Transcreation of the Bhagavad Gita | Ashok K. Malhotra | 1998 |

| You Know Me: The Gita | Irina Gajjar | 1999 |

| The Bhagavad Gita, Your Charioteer in the Battlefield of Life | R.K. Piparaiya | 1999 |

| The Bhagavad Gita, an Original Translation | V. Jayaram | 2000 |

| Bhagavad Gita: A Walkthrough for Westerners | Jack Hawley | 2001 |

| Bhagavad Gita[note 22] | Rosetta Williams | 2001 |

| The Bhagavad Gita of Order | Anand Aadhar Prabhu | 2001 |

| Bhagavad Gita: The Song Divine | Carl E. Woodham | 2001 |

| The Bhagavat Gita (as part of the Wisdom Bible) | Sanderson Beck | 2001 |

| Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation | Stephen Mitchell | 2002 |

| Bhagavad Gita As a Living Experience | Wilfried Huchzermeyer and Jutta Zimmermann | 2002 |

| Bhagvad Gita | Alan Jacobs | 2002 |

| Bhagavad Gita: Translation and Commentary | Veeraswamy Krishnaraj | 2002 |

| The Bhagavad Gita | Richard Prime | 2003 |

| The Sacred Song: A New Translation of the Bhagavad Gita for the Third Millennium | McComas Taylor and Richard Stanley | 2004 |

| The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation | George Thompson | 2008 |

| The Bhagavad Gita, A New Translation | Georg Feuerstein | 2011 |

| The Bhagavad Gita: A Text and Commentary for Students | Jeaneane D. Fowler | 2012 |

| The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation | Gavin Flood, Charles Martin | 2012 |

| Bhagavad Gita: Rhythm of Krishna (Gita in Rhymes) | Sushrut Badhe | 2015 |

| Philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita | Keya Maitra | 2018 |

| The Bhagavad Gita Chapter 1 to 13 – English ISBN 978-93-87578-96-8 | Ravi Shankar | 2018 |

| The Bhagavad Gita[note 23] | Bibek Debroy | 2019 |

| The Teachings of Bhagavad Gita: Timeless Wisdom for the Modern Age[115] | Richa Tilokani | 2021 |

According to the exegesis scholar Robert Minor, the Gita is "probably the most translated of any Asian text", but many modern versions heavily reflect the views of the organization or person who does the translating and distribution. In Minor's view, the Harvard scholar Franklin Edgerton's English translation and Richard Garbe's German translation are closer to the text than many others.[116] According to Larson, the Edgerton translation is remarkably faithful, but it is "harsh, stilted, and syntactically awkward" with an "orientalist" bias and lacks "appreciation of the text's contemporary religious significance".[99]:524

The Gita in other languages

The Gita has also been translated into European languages other than English. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, in the Mughal Empire, multiple discrete Persian translations of the Gita were completed.[117] In 1808, passages from the Gita were part of the first direct translation of Sanskrit into German, appearing in a book through which Friedrich Schlegel became known as the founder of Indian philology in Germany.[118] The most significant French translation of the Gita, according to J. A. B. van Buitenen, was published by Emile Senart in 1922.[119] Swami Rambhadracharya released the first Braille version of the scripture, with the original Sanskrit text and a Hindi commentary, on 30 November 2007.[web 2]

The Gita Press has published the Gita in multiple Indian languages.[120] R. Raghava Iyengar translated the Gita into Tamil in sandam metre poetic form.[121] The Bhaktivedanta Book Trust associated with ISKCON has re-translated and published A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada's 1972 English translation of the Gita in 56 non-Indian languages.[122][123][note 24] Vinoba Bhave has written the Geeta in Marathi language as Geetai i.e. Mother Geeta in the similar shloka form.

Paramahansa Yogananda's commentary on the Bhagavad Gita called God Talks with Arjuna: The Bhagavad Gita has been translated into Spanish, German, Thai and Hindi so far. The book is significant in that unlike other commentaries of the Bhagavad Gita, which focus on karma yoga, jnana yoga, and bhakti yoga in relation to the Gita, Yogananda's work stresses the training of one's mind, or raja yoga.[126]

Bhashya (commentaries)

Bhagavad Gita integrates various schools of thought, notably Vedanta, Samkhya and Yoga, and other theistic ideas. It remains a popular text for commentators belonging to various philosophical schools. However, its composite nature also leads to varying interpretations of the text and historic scholars have written bhashya (commentaries) on it.[127] According to Mysore Hiriyanna, the Gita is "one of the hardest books to interpret, which accounts for the numerous commentaries on it–each differing from the rest in one essential point or the other".[128]

According to Richard Davis, the Gita has attracted much scholarly interest in Indian history and some 227 commentaries have survived in the Sanskrit language alone.[129] It has also attracted commentaries in regional vernacular languages for centuries, such as the one by Sant (Saint) Dnyaneshwar in Marathi language (13th century).[130]

Classical commentaries

The Bhagavad Gita is referred to in the Brahma Sutras, and numerous scholars including Shankara, Bhaskara, Abhinavagupta of Shaivism tradition, Ramanuja and Madhvacharya wrote commentaries on it.[131][132] Many of these commentators state that the Gita is "meant to be a moksa-shastra (moksasatra), and not a dharmasastra, an arthasastra or a kamasastra", states Sharma.[133]

Śaṅkara (c. 800 CE)

The oldest and most influential surviving commentary was published by Adi Shankara (Śaṅkarācārya).[134][135] Shankara interprets the Gita in a monist, nondualistic tradition (Advaita Vedanta).[136] Shankara prefaces his comments by stating that the Gita is popular among the laity, that the text has been studied and commented upon by earlier scholars (these texts have not survived), but "I have found that to the laity it appears to teach diverse and quite contradictory doctrines". He calls the Gita as "an epitome of the essentials of the whole Vedic teaching".[137] To Shankara, the teaching of the Gita is to shift an individual's focus from the outer, impermanent, fleeting objects of desire and senses to the inner, permanent, eternal atman-Brahman-Vasudeva that is identical, in everything and in every being.[138]

Abhinavagupta was a theologian and philosopher of the Kashmir Shaivism (Shiva) tradition.[135] He wrote a commentary on the Gita as Gitartha-Samgraha, which has survived into the modern era. The Gita text he commented on, is slightly different recension than the one of Adi Shankara. He interprets its teachings in the Shaiva Advaita (monism) tradition quite similar to Adi Shankara, but with the difference that he considers both soul and matter to be metaphysically real and eternal. Their respective interpretations of jnana yoga are also somewhat different, and Abhinavagupta uses Atman, Brahman, Shiva, and Krishna interchangeably. Abhinavagupta's commentary is notable for its citations of more ancient scholars, in a style similar to Adi Shankara. However, the texts he quotes have not survived into the modern era.[139]

Rāmānuja (c. 1100 CE)

Ramanuja was a Hindu theologian, philosopher, and an exponent of the Sri Vaishnavism (Vishnu) tradition in 11th and early 12th century. Like his Vedanta peers, Ramanuja wrote a bhashya (commentary) on the Gita.[140] Ramanuja's disagreed with Adi Shankara's interpretation of the Gita as a text on nondualism (Self and Brahman are identical), and instead interpreted it as a form of dualistic and qualified monism philosophy (Vishishtadvaita).[141][142]

Madhva (c. 1250 CE)

Madhva, a commentator of the Dvaita (modern taxonomy) Tatvavada (actually quoted by Madhva) Vedanta school,[135] wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, which exemplifies the thinking of the Tatvavada school (Dvaita Vedanta).[134] According to Christopher Chapelle, in the Madhva's school there is "an eternal and complete distinction between the Supreme, the many souls, and matter and its divisions".[143] His commentary on the Gita is called Gita Bhāshya. Madhva's commentary has attracted secondary works by pontiffs of the Dvaita Vedanta monasteries such as Padmanabha Tirtha, Jayatirtha, and Raghavendra Tirtha.[144]

Keśava Kāśmīri (c. 1479 CE)

Keśava Kāśmīri Bhaṭṭa, a commentator of Dvaitādvaita Vedanta school, wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita by the name Tattva-prakāśikā. The text states that Dasasloki – possibly authored by Nimbarka – teaches the essence of the Gita; the Gita tattva prakashika interprets the Gita also in a hybrid monist-dualist manner.[145][146]

Vallabha (1481–1533 CE)

Vallabha the proponent of "Suddhadvaita" or pure non-dualism, wrote a commentary on the Gita, the "Sattvadipika". According to him, the true Self is the Supreme Brahman. Bhakti is the most important means of attaining liberation.

Gauḍīya Vaiṣṇava Commentaries

- Chaitanya Mahaprabhu (b. 1486 CE) commentaries on various parts of the Gita are in the Gaudiya Vaishnavism Bhakti (acintya bhedabheda)[note 25] Vedanta tradition; in part a foundation of the ISKCON (Hare Krishna) interpretation of the Gita[148][147]

Others

Other classical commentators include

- Bhāskara (c. 900 CE) disagreed with Adi Shankara, wrote his own commentary on both Bhagavad Gita and Brahma Sutras in the Bhedābheda tradition.[145] According to Bhaskara, the Gita is essentially Advaita, but not quite exactly, suggesting that "the Atman (soul) of all beings are like waves in the ocean that is Brahman". Bhaskara also disagreed with Shankara's formulation of the Maya doctrine, stating that prakriti, atman and Brahman are all metaphysically real.[145]

- Yamunacharya, Ramanuja's teacher summarised the teachings of the Bhagavadgita in his Gitartha sangraham.

- Nimbarka (1162 CE) followed Bhaskara, but it is unclear if he ever wrote the commentary; the commentary Gitatattvaprakashika is generally attributed to a student named Kesava Bhatta in his tradition; the text states that Dasasloki – possibly authored by Nimbarka – teaches the essence of the Gita; the Gita tattva prakashika interprets the Gita also in a hybrid monist-dualist manner.[145][146]

- Dnyaneshwar (1290 CE),[130][149] the commentary is titled Dnyaneshwari also called Jnaneshwari or Bhavarthadipika;[150] it is the oldest surviving literary work in the Marathi language,[151] one of the foundations of the Varkari tradition in Maharashtra (Bhakti movement, Eknath, Tukaram);[151][152][153] the commentary interprets the Gita in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[154] Dnyaneshwar belonged to the Nath yogi tradition. His commentary on the Gita is notable for stating that it is the devotional commitment and love with inner renunciation that matters, not the name Krishna or Shiva, either can be used interchangeably.[155][156]

- Vallabha II, descendant of Vallabha (1479 CE) commentary Tattvadeepika is in the Suddha-Advaita tradition[127]

- Madhusudana Saraswati commentary Gudhartha Deepika is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Hanumat's commentary Paishacha-bhasya is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Anandagiri's commentary Bhashya-vyakhyanam is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Nilkantha's commentary Bhava-pradeeps is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Shreedhara's (1400 CE) commentary Avi gita is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Dhupakara Shastri's commentary Subodhini is in the Advaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Raghuttama Tirtha (1548-1596), commentary Prameyadīpikā Bhavabodha is in the Dvaita Vedanta tradition[157]

- Raghavendra Tirtha (1595-1671), commentary Artha samgraha is in the Dvaita Vedanta tradition[127]

- Vanamali Mishra (1650-1720), Gitagudharthacandrika is quite similar to Madhvacharya's commentary and is in the Dvaita Vedanta tradition[158]

- Purushottama (1668–1781 CE), Vallabha's follower, also wrote a commentary on Bhagavadgita

Modern-era commentaries

- Among notable modern commentators of the Bhagavad Gita are Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Vinoba Bhave, Mahatma Gandhi (who called its philosophy Anasakti Yoga), Sri Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, B. N. K. Sharma, Osho, and Chinmayananda. Chinmayananda took a syncretistic approach to interpret the text of the Gita.[159][160]

- Tilak wrote his commentary Shrimadh Bhagavad Gita Rahasya while in jail during the period 1910–1911 serving a six-year sentence imposed by the colonial government in India for sedition.[161] While noting that the Gita teaches possible paths to liberation, his commentary places most emphasis on Karma yoga.[162]

- No book was more central to Gandhi's life and thought than the Bhagavad Gita', which he referred to as his "spiritual dictionary".[163] During his stay in Yeravda jail in 1929,[163] Gandhi wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita in Gujarati. The Gujarati manuscript was translated into English by Mahadev Desai, who provided an additional introduction and commentary. It was published with a foreword by Gandhi in 1946.[164][165]

- The version by A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, entitled Bhagavad-Gita as It Is, is "by far the most widely distributed of all English Gīta translations" due to the efforts of ISKCON.[123] Its publisher, the Bhaktivēdānta Book Trust, estimates sales at twenty-three million copies, a figure which includes the original English edition and secondary translations into fifty-six other languages.[123] The Prabhupada commentary interprets the Gita in the Gaudiya Vaishnavism tradition of Chaitanya,[123] quite similar to Madhvacharya's Dvaita Vēdanta ideology.[166] It presents Krishna as the Supreme, a means of saving mankind from the anxiety of material existence through loving devotion. Unlike in Bengal and nearby regions of India where the Bhagavata Purana is the primary text for this tradition, the devotees of Prabhupada's ISKCON tradition have found better reception for their ideas by those curious in the West through the Gita, according to Richard Davis.[123]

- In 1966, Mahārishi Mahesh Yogi published a partial translation.[123]

- An abridged version with 42 verses and commentary was published by Ramana Maharishi.[167]

- Bhagavad Gita – The song of God, is a commentary by Swami Mukundananda.[168]

- Paramahansa Yogananda's two-volume commentary on the Bhagavad Gita, called God Talks with Arjuna: The Bhagavad Gita, was released 1995 and is available in 5 language.[169] The book is significant in that unlike other commentaries of the Bhagavad Gita, which focus on karma yoga, jnana yoga, and bhakti yoga in relation to the Gita, Yogananda's work stresses the training of one's mind, or raja yoga.[126] It is published by Self-Realization Fellowship/Yogoda Satsanga Society of India.

- Eknath Easwaran's commentary interprets the Gita for his collection of problems of daily modern life.[170]

- Other modern writers such as Swami Parthasarathy and Sādhu Vāsvāni have published their own commentaries.[171]

- Academic commentaries include those by Jeaneane Fowler,[172] Ithamar Theodor,[173] and Robert Zaehner.[174]

- A collection of Christian commentaries on the Gita has been edited by Catherine Cornille, comparing and contrasting a wide range of views on the text by theologians and religion scholars.[175]

Reception

Narendra Modi, the 14th prime minister of India, called the Bhagavad Gita "India's biggest gift to the world".[176] Modi gave a copy of it to the then President of the United States of America, Barack Obama in 2014 during his U.S. visit.[177]

With its translation and study by Western scholars beginning in the early 18th century, the Bhagavad Gita gained a growing appreciation and popularity.[web 1] According to the Indian historian and writer Khushwant Singh, Rudyard Kipling's famous poem "If—" is "the essence of the message of The Gita in English."[178]

Praise and popularity

The Bhagavad Gita has been highly praised, not only by prominent Indians including Mahatma Gandhi and Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan,[179] but also by Aldous Huxley, Henry David Thoreau, J. Robert Oppenheimer,[180] Ralph Waldo Emerson, Carl Jung, Herman Hesse,[181][182] and Bülent Ecevit.[183]

At a time when Indian nationalists were seeking an indigenous basis for social and political action against colonial rule, Bhagavad Gita provided them with a rationale for their activism and fight against injustice.[184] Bal Gangadhar Tilak and Mahatma Gandhi used the text to help inspire the Indian independence movement.[note 26][note 27] Mahatma Gandhi expressed his love for the Gita in these words:

I find a solace in the Bhagavadgītā that I miss even in the Sermon on the Mount. When disappointment stares me in the face and all alone I see not one ray of light, I go back to the Bhagavadgītā. I find a verse here and a verse there and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming tragedies – and my life has been full of external tragedies – and if they have left no visible, no indelible scar on me, I owe it all to the teaching of Bhagavadgītā.[185][186]

Jawaharlal Nehru, the first Prime Minister of independent India, commented on the Gita:

The Bhagavad-Gita deals essentially with the spiritual foundation of human existence. It is a call of action to meet the obligations and duties of life; yet keeping in view the spiritual nature and grander purpose of the universe.[187]

A. P. J. Abdul Kalam, 11th President of India, despite being a Muslim, used to read Bhagavad Gita and recite mantras.[188][189][190][191][192]

J. Robert Oppenheimer, American physicist and director of the Manhattan Project, learned Sanskrit in 1933 and read the Bhagavad Gita in the original form, citing it later as one of the most influential books to shape his philosophy of life. Oppenheimer later recalled that, while witnessing the explosion of the Trinity nuclear test, he thought of verses from the Bhagavad Gita (XI,12):

दिवि सूर्यसहस्रस्य भवेद्युगपदुत्थिता यदि भाः सदृशी सा स्याद्भासस्तस्य महात्मनः ॥११- १२॥ If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one ...[193]

Years later he would explain that another verse had also entered his head at that time:

We knew the world would not be the same. A few people laughed, a few people cried. Most people were silent. I remembered the line from the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita; Vishnu is trying to persuade the Prince that he should do his duty and, to impress him, takes on his multi-armed form and says, 'Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.' I suppose we all thought that, one way or another.[194][note 28]

Ralph Waldo Emerson, remarked the following after his first study of the Gita, and thereafter frequently quoted the text in his journals and letters, particularly the "work with inner renunciation" idea in his writings on man's quest for spiritual energy:[197]

I owed – my friend and I owed – a magnificent day to the Bhagavad Geeta. It was the first of books; it was as if an empire spoke to us, nothing small or unworthy, but large, serene, consistent, the voice of an old intelligence which in another age and climate had pondered and thus disposed of the same questions which exercise us.[197]

The world's largest Bhagavad Gita is in the ISKCON Temple Delhi, which is the world's largest sacred book of any religion. It weighs 800 kg and measures over 2.8 metres. It was unveiled by Narendra Modi, the Prime Minister of India on 26 February 2019.[198][199] On 27 February 2021, the Bhagavad Gita, was launched into outer space in a SD card, on a PSLV-C51 rocket launched by the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) from the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota.[200]

Criticisms and apologetics

War with self

The Gita presents its teaching in the context of a war where the warrior Arjuna is in inner crisis about whether he should renounce and abandon the battlefield, or fight and kill. He is advised by Krishna to do his sva-dharma, a term that has been variously interpreted. According to the Indologist Paul Hacker, the contextual meaning in the Gita is the "dharma of a particular varna".[201] Neo-Hindus such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, states Hacker, have preferred to not translate it in those terms, or "dharma" as religion, but leave Gita's message as "everyone must follow his sva-dharma".[202] According to Chatterjee, the Hindus already understand the meaning of that term. To render it in English for non-Hindus for its better understanding, one must ask what is the sva-dharma for the non-Hindus? The Lord, states Chatterjee, created millions and millions of people, and he did not ordain dharma only for Indians [Hindus] and "make all the others dharma-less", for "are not the non-Hindus also his children"? According to Chatterjee, the Krishna's religion of Gita is "not so narrow-minded".[202] This argument, states Hacker, is an attempt to "universalize Hinduism".[202]

The Gita has been cited and criticized as a Hindu text that supports varna-dharma and the caste system.[203][204][205] B. R. Ambedkar, born in a Dalit family and the principal architect of the Constitution of India, criticized the text for its stance on caste and for "defending certain dogmas of religion on philosophical grounds".[205] According to Jimmy Klausen, Ambedkar in his essay Krishna and his Gita stated that the Gita was a "tool" of Brahmanical Hinduism and for its latter-day saints such as Mahatma Gandhi and Lokmanya Tilak. To Ambedkar, states Klausen, it is a text of "mostly barbaric, religious particularisms" offering "a defence of the kshatriya duty to make war and kill, the assertion that varna derives from birth rather than worth or aptitude, and the injunction to perform karma" neither perfunctorily nor egotistically.[206] Similar criticism of the Gita has been published by Damodar Dharmananda Kosambi, another Marxist historian.[207]

The humble sage, by virtue of true knowledge, sees with equal vision a learned and gentle brahmana, a cow, an elephant, a dog and a dog-eater [outcaste]

— Bhagavad Gita,Chapter 5, Verse 18[208]

Nadkarni and Zelliot present the opposite view, citing early Bhakti saints of the Krishna-tradition such as the 13th-century Dnyaneshwar.[209] According to Dnyaneshwar, the Gita starts off with the discussion of sva-dharma in Arjuna's context but ultimately shows that caste differences are not important. For Dnyaneshwar, people err when they see themselves distinct from each other and Krishna, and these distinctions vanish as soon as they accept, understand and enter with love unto Krishna.[210][211]

According to Swami Vivekananda, sva-dharma in the Gita does not mean "caste duty", rather it means the duty that comes with one's life situation (mother, father, husband, wife) or profession (soldier, judge, teacher, doctor). For Vivekananda, the Gita was an egalitarian scripture that rejected caste and other hierarchies because of its verses such as 13.27—28, which states "He who sees the Supreme Lord dwelling equally in all beings, the Imperishable in things that perish, he sees verily. For seeing the Lord as the same everywhere present, he does not destroy the Self by the Self, and thus he goes to the highest goal."[212][note 29]

Aurobindo modernises the concept of dharma and svabhava by internalising it, away from the social order and its duties towards one's personal capacities, which leads to a radical individualism,[215] "finding the fulfilment of the purpose of existence in the individual alone."[215] He deduced from the Gita the doctrine that "the functions of a man ought to be determined by his natural turn, gift, and capacities",[215] that the individual should "develop freely"[215] and thereby would be best able to serve society.[215]

Gandhi's view differed from Aurobindo's view.[216] He recognised in the concept of sva-dharma his idea of svadeshi (sometimes spelled swadeshi), the idea that "man owes his service above all to those who are nearest to him by birth and situation."[216] To him, svadeshi was "sva-dharma applied to one's immediate environment."[217]

According to Jacqueline Hirst, the universalist neo-Hindu interpretations of dharma in the Gita is modernism, though any study of pre-modern distant foreign cultures is inherently subject to suspicions about "control of knowledge" and bias on the various sides.[218] Hindus have their own understanding of dharma that goes much beyond the Gita or any particular Hindu text.[218] Further, states Hirst, the Gita should be seen as a "unitary text" in its entirety rather than a particular verse analyzed separately or out of context. Krishna is presented as a teacher who "drives Arjuna and the reader beyond initial preconceptions". The Gita is a cohesively knit pedagogic text, not a list of norms.[219]

Modern-Hinduism

Novel interpretations of the Gita, along with apologetics on it, have been a part of the modern era revisionism and renewal movements within Hinduism.[220] Bankim Chandra Chatterji, the author of Vande Mataram – the national song of India, challenged orientalist literature on Hinduism and offered his interpretations of the Gita, states Ajit Ray.[221][222] Bal Gangadhar Tilak interpreted the karma yoga teachings in Gita as a "doctrine of liberation" taught by Hinduism,[223] while S Radhakrishnan stated that the Bhagavad Gita teaches a universalist religion and the "essence of Hinduism" along with the "essence of all religions", rather than a private religion.[224]

Vivekananda's works contained numerous references to the Gita, such as his lectures on the four yogas – Bhakti, Jnana, Karma, and Raja.[225] Through the message of the Gita, Vivekananda sought to energise the people of India to reclaim their dormant but strong identity.[226] Aurobindo saw Bhagavad Gita as a "scripture of the future religion" and suggested that Hinduism had acquired a much wider relevance through the Gita.[227] Sivananda called Bhagavad Gita "the most precious jewel of Hindu literature" and suggested its introduction into the curriculum of Indian schools and colleges.[228]

According to Ronald Neufeldt, it was the Theosophical Society that dedicated much attention and energy to the allegorical interpretation of the Gita, along with religious texts from around the world, after 1885 and given H. P. Blavatsky, Subba Rao and Anne Besant writings.[229] Their attempt was to present their "universalist religion". These late 19th-century theosophical writings called the Gita as a "path of true spirituality" and "teaching nothing more than the basis of every system of philosophy and scientific endeavor", triumphing over other "Samkhya paths" of Hinduism that "have degenerated into superstition and demoralized India by leading people away from practical action".[229]

Political violence

In the Gita, Krishna persuades Arjuna to wage war where the enemy includes some of his own relatives and friends. In light of the Ahimsa (non-violence) teachings in Hindu scriptures, the Gita has been criticized as violating the Ahimsa value, or alternatively, as supporting political violence.[230] The justification of political violence when peaceful protests and all else fails, states Varma, has been a "fairly common feature of modern Indian political thought" along with the "mighty antithesis of Gandhian thought on non-violence". During the independence movement in India, Hindus considered active "burning and drowning of British goods" while technically illegal under colonial legislation, were viewed as a moral and just war for the sake of liberty and righteous values of the type Gita discusses.[231] According to Paul Schaffel the influential Hindu nationalist V.D. Savarkar "often turned to Hindu scripture such as the Bhagavad Gita, arguing that the text justified violence against those who would harm Mother India."[232]

Mahatma Gandhi credited his commitment for ahimsa to the Gita. For Gandhi, the Gita is teaching that people should fight for justice and righteous values, that they should never meekly suffer injustice to avoid a war. According to the Indologist Ananya Vajpeyi, the Gita does not elaborate on the means or stages of war, nor on ahimsa, except for stating that "ahimsa is virtuous and characterizes an awakened, steadfast, ethical man" in verses such as 13.7–10 and 16.1–5.[233] For Gandhi, states Vajpeyi, ahimsa is the "relationship between self and other" while he and his fellow Indians battled against the colonial rule. Gandhian ahimsa is in fact "the essence of the entire Gita", according to Vajpeyi.[233] The teachings of the Gita on ahimsa are ambiguous, states Arvind Sharma, and this is best exemplified by the fact that Nathuram Godse stated the Gita as his inspiration to do his dharma after he assassinated Mahatma Gandhi.[234] Thomas Merton, the Trappist monk and author of books on Zen Buddhism, concurs with Gandhi and states that the Gita is not teaching violence nor propounding a "make war" ideology. Instead, it is teaching peace and discussing one's duty to examine what is right and then act with pure intentions, when one's faces difficult and repugnant choices.[235]

Adaptations

Philip Glass retold the story of Gandhi's early development as an activist in South Africa through the text of the Gita in the opera Satyagraha (1979). The entire libretto of the opera consists of sayings from the Gita sung in the original Sanskrit.[web 3]

In Douglas Cuomo's Arjuna's dilemma, the philosophical dilemma faced by Arjuna is dramatised in operatic form with a blend of Indian and Western music styles.[web 4]

The 1993 Sanskrit film, Bhagavad Gita, directed by G. V. Iyer won the 1993 National Film Award for Best Film.[web 5][web 6]

The 1995 novel by Steven Pressfield, and its adaptation as the 2000 golf movie The Legend of Bagger Vance by Robert Redford has parallels to the Bhagavad Gita, according to Steven J. Rosen. Steven Pressfield acknowledges that the Gita was his inspiration, the golfer character in his novel is Arjuna, the caddie is Krishna, states Rosen. The movie, however, uses the plot but glosses over the teachings unlike in the novel.[236]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Krishna states that the body is impermanent and dies, never the immortal soul, the latter is either reborn or achieves moksha for those who have understood the true spiritual path he teaches in the Gita.[web 1]

- ↑ The Bhagavad Gita also integrates theism and transcendentalism[web 1] or spiritualmonism,[11] and identifies a God of personal characteristics with the Brahman of the Vedic tradition.[web 1]

- ↑ This legend is depicted with Ganesha (Vinayaka) iconography in Hindu temples where he is shown with a broken right tusk and his right arm holds the broken tusk as if it was a stylus.[27][28]

- ↑ The debate about the relationship between the Gita and the Mahabharata is historic, in part the basis for chronologically placing the Gita and its authorship. The Indologist Franklin Edgerton was among the early scholars and a translator of the Gita who believed that the Gita was a later composition that was inserted into the epic, at a much later date, by a creative poet of great intellectual power intimately aware of emotional and spiritual aspects of human existence.[35] Edgerton's primary argument was that it makes no sense that two massive armies facing each other on a battlefield will wait for two individuals to have a lengthy dialogue. Further, he states that the Mahabharata has numerous such interpolations and inserting the Gita would not be unusual.[35] In contrast, the Indologist James Fitzgerald states, in a manner similar to van Buitenen, that the Bhagavad Gita is the centerpiece and essential to the ideological continuity in the Mahabharata, and the entire epic builds up to the fundamental dharma questions in the Gita. This text, states Fitzgerald, must have been integral to the earliest version of the epic.[36]

- ↑ According to Basham, passionately theistic verses are found, for example, in chapters 4, 7, 9, 10, 11, 14.1–6 with 14.29, 15, 18.54–78; while more philosophical verses with one or two verses where Krishna identifies himself as the highest god are found, for example, in chapters 2.38–72, 3, 5, 6, 8, 13 and 14.7–25, 16, 17 and 18.1–53. Further, states Basham, the verses that discuss Gita's "motiveless action" doctrine was probably authored by someone else and these constitute the most important ethical teaching of the text.[38]

- ↑ According to the Indologist and Sanskrit literature scholar Moriz Winternitz, the founder of the early Buddhist Sautrāntika school named Kumaralata (1st century CE) mentions both Mahabharata and Ramayana, along with early Indian history on writing, art and painting, in his Kalpanamanditika text. Fragments of this early text have survived into the modern era.[43]

- ↑ The Indologist Étienne Lamotte used a similar analysis to conclude that the Gita in its current form likely underwent one redaction that occurred in the 3rd or 2nd century BCE.[45]

- ↑ They state that the authors of the Bhagavad Gita must have seen the appeal of the soteriologies found in "the heterodox traditions of Buddhism and Jainism" as well as those found in " the orthodox Hindu traditions of Samkhya and Yoga". The Gita attempts to present a harmonious, universalist answer, state Deutsch and Dalvi.[12]

- ↑ This is called the doctrine of nishakama karma in Hinduism.[76][77]

- ↑ Sanskrit scholar Barbara Stoler Miller produced a translation in 1986 intended to emphasise the poem's influence and current context within English Literature, especially the works of T.S. Eliot, Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson.[105] The translation was praised by scholars as well as literary critics.[106][107] Similarly, the Hinduism scholar Jeaneane Fowler's translation and student text has been praised for its comprehensive introduction, quality of translation, and commentary.[108]

- ↑ Second edition in 1898

- ↑ Or Bhagavat-Gita, Edwin Arnold, reprinted by Dover Publications, New York, 1900

- ↑ Reprinted by Theosophical University Press, Los Angeles, California, 1967

- ↑ Reprinted by Theosophical Publishing House, Los Angeles, California, 1987

- ↑ Eventually published by Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, 1946.

- ↑ Reprint 1995

- ↑ Reprint 1974

- ↑ Only the first six chapters were translated

- ↑ Reprint 1996

- ↑ A trans-creation rather than translation

- ↑ Originally translated in 1933

- ↑ Implicitly targeted at children, or young adults

- ↑ Originally translated in 2005 and also based on Critical Edition by BORI

- ↑ Teachings of International Society for Krishna Consciousness (ISKCON), a Gaudiya Vaishnava religious organisation which spread rapidly in North America in the 1970s and 1980s, are based on a translation of the Gita called Bhagavad-Gītā As It Is by A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada.[124] These teachings are also illustrated in the dioramas of Bhagavad-gita Museum in Los Angeles, California.[125]

- ↑ According to Edwin Bryant and Maria Ekstrand, this school incorporates and integrates aspects of "qualified monism, dualism, monistic dualism, and pure nondualism".[147]

- ↑ For B.G. Tilak and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi as notable commentators see: Gambhirananda 1997, p. xix

- ↑ For notability of the commentaries by B.G. Tilak and Gandhi and their use to inspire the independence movement see: Sargeant 2009, p. xix

- ↑ Oppenheimer spoke these words in the television documentary The Decision to Drop the Bomb (1965).[194] Oppenheimer read the original text in Sanskrit, "kālo'smi lokakṣayakṛtpravṛddho lokānsamāhartumiha pravṛttaḥ" (XI,32), which he translated as "I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds". In the literature, the quote usually appears in the form shatterer of worlds, because this was the form in which it first appeared in print, in Time magazine on 8 November 1948.[195] It later appeared in Robert Jungk's Brighter than a Thousand Suns: A Personal History of the Atomic Scientists (1958),[193] which was based on an interview with Oppenheimer. See Hijiya, The Gita of Robert Oppenheimer[196]

- ↑ This view in the Gita of the unity and equality in the essence of all individual beings as the hallmark of a spiritually liberated, wise person is also found in the classical and modern commentaries on Gita verses 5.18, 6.29, and others.[213][214] Scholars have contested Kosambi's criticism of the Gita based on its various sections on karma yoga, bhakti yoga and jnana yoga.[207]

References

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Davis 2014, p. 2.

- ↑ The Song Celestial, Or, Bhagavad-gîtâ (from the Mahâbhârata) Being a Discourse Between Arjuna, Prince of India, and the Supreme Being Under the Form of Krishna. Roberts Bros. 1885. pp. Book one the first, page 19.

- ↑ Easwaran 2007, pp. 111–122.

- ↑ Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi 2004, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sargeant 2009, pp. x–xviii.

- ↑ Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi 2004, p. 97

- ↑ Ronald Neufeldt. Robert Neil Minor (ed.). Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita. State University of New York Press. pp. 31–33. ISBN 978-1-4384-1325-9.

- ↑ M.V. Nadkarni 2016, pp. 15.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi 2004, p. 61.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Scheepers 2000.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Raju 1992, p. 211.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi 2004, pp. 61–62.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Catherine A. Robinson (2014). Interpretations of the Bhagavad-Gita and Images of the Hindu Tradition: The Song of the Lord. Taylor & Francis. pp. viii–ix. ISBN 978-1-134-27891-6.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 J.A.B. van Buitenen 2013, pp. 6–7, Quote: "Its [Bhagavadgita's] importance as a religious text is demonstrated by its uniquely pan-Hindu influence".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Gerald James Larson (2009). Jacob Neusner (ed.). World Religions in America, Fourth Edition: An Introduction. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1-61164-047-2.

- ↑ "Mahatma Gandhi | Biography, Accomplishments, & Facts". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 16 May 2017.

- ↑ Swami Prabhavananda; Christopher Isherwood (2002). Bhagavad-Gita: The words of God. Signet Classic. ISBN 978-0-451-52844-5.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedEBG - ↑ Catherine Cornille (2006). Song Divine: Christian Commentaries on the Bhagavad Gītā. Peeters Publishers. ISBN 978-90-429-1769-9.

- ↑ Sachindra Kumar Majumdar (1991). The Bhagavad Gita: A Scripture for the Future. Asian Humanities Press. ISBN 978-0-89581-885-0.

- ↑ Braja Dulal Mookherjee (2002). The Essence of Bhagavad Gita. Academic Publishers. p. 18. ISBN 978-81-87504-40-5., Quote: "Bhagavad Gita means that Celestial Song."

- ↑ Sharma 1986, p. ix.

- ↑ Fowler 2012, p. xxvi

- ↑ M.V. Nadkarni 2016, pp. 16.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Alexus McLeod (2014). Understanding Asian Philosophy. A&C Black. pp. 168–169. ISBN 978-1-78093-631-4.

- ↑ David Slavitt (2015). Mahabharata. Northwestern University Press. p. vii. ISBN 978-0-8101-3060-9.

- ↑ T.A. Gopinatha Rao (1985). Elements of Hindu Iconography. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. xvii, 58–61. ISBN 978-81-208-0878-2.

- ↑ Lawrence Cohen (1991). Robert L. Brown (ed.). Ganesh: Studies of an Asian God. State University of New York Press. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-7914-0656-4.

- ↑ George M. Williams (2008). Handbook of Hindu Mythology. Oxford University Press. p. 304. ISBN 978-0-19-533261-2., Quote: "Veda Vyasa was said to have edited the four Vedas and authored the Puranas and the Mahabharata. Accomplishing all that would require a human who lived several thousand years, so scholars do place the story of his achievements as those of one man in the area of mythology."

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1998, p. 25 with footnote 1.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Swami Vivekananda (1958). The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda, Volume 4 (12th ed.). Advaita Ashram. pp. 102–104.

- ↑ Alexus McLeod (2014). Understanding Asian Philosophy. A&C Black. pp. 169–170. ISBN 978-1-78093-631-4.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 J.A.B. van Buitenen 2013, pp. 5–6

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Franklin Edgerton (1952). The Bhagavad Gita, Part 2. Harvard University Press. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ James L. Fitzgerald (1983). "The Great Epic of India as Religious Rhetoric: A Fresh Look at the "Mahābhārata"". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 51 (4): 615–619, context: 611–630.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbasham1991p85 - ↑ Fowler 2012, p. xxiv.

- ↑ J.A.B. van Buitenen 2013, pp. 6, Quote: "ca. 200 BC is a likely date"..

- ↑ Sharma 1986, p. 3.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Upadhyaya 1998, pp. 16–18.

- ↑ Moriz Winternitz (1996). A History of Indian Literature: Buddhist literature and Jaina literature. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 258–259. ISBN 978-81-208-0265-0.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1998, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ Étienne Lamotte (1929). Notes sur la Bhagavadgita. Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner. pp. 126–127.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Arthur Llewellyn Basham (1991). The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism. Oxford University Press. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-0-19-507349-2.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 Sargeant 2009, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Heather Elgood (2000). Hinduism and the Religious Arts. A&C Black. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0-304-70739-3.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Fowler 2012, pp. xxiv–xxiv.

- ↑ College, Bard. "Richard H. Davis". www.bard.edu. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- ↑ Davis 2014, p. 3.

- ↑ James G. Lochtefeld (2001). The Illustrated Encyclopedia of Hinduism, Volume 1. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8239-3179-8.

- ↑ Keya Maitra (2018). Philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita: A Contemporary Introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 5–6. ISBN 978-1-350-04017-5.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 NV Isaeva (1992), Shankara and Indian Philosophy, State University of New York Press, ISBN 978-0-7914-1281-7, p. 35 with footnote 30

- ↑ Sargeant 2009, p. x.

- ↑ Nicholson 2010, p. 7.

- ↑ Singh 2005, p. 37.

- ↑ Nakamura 1950, p. 3.

- ↑ Flood 1996, pp. 231–232, 238.

- ↑ Ronald Neufeldt (1986). Robert Neil Minor (ed.). Modern Indian Interpreters of the Bhagavad Gita. State University of New York Press. pp. 11–12, 213. ISBN 978-0-88706-297-1.

- ↑ Coburn, Thomas B. (1984), "'Scripture' in India: Towards a Typology of the Word in Hindu Life", Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 52 (3): 435–59, doi:10.1093/jaarel/52.3.435, JSTOR 1464202

- ↑ Tapasyananda 1990, p. 1

- ↑ Swami Prabhavananda (1964). Bhagavad Gita – The Song of God. New American Library. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-1-4474-8104-1.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Upadhyaya 1998, pp. 10–12 with footnote 1 on p. 11.

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Minor 1982, pp. li–lii, Quote: "the Kashmir recension is a later reading of the Gita." (note the different views of F Otto Schrader from those of SK Belvalkar as well as JAB van Buitenen.).

- ↑ Maitra 2018, pp. 5, 26–30, 143.

- ↑ Robinson 2006, pp. 69–70, 95–100.

- ↑ Robinson 2006, p. 95.

- ↑ Minor 1986, pp. 74–75, 81.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Gavin Flood (2004). The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 85–89 with notes. ISBN 978-0-521-60401-7.

- ↑ Robin Gill (2017). Moral Passion and Christian Ethics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–130. ISBN 978-1-107-17682-9.

- ↑ Robert Charles Zaehner (1973). The Bhagavad-gītā. Oxford University Press. pp. 187, 200. ISBN 978-0-19-501666-6.

- ↑ Nikam, N.A. (1952). "A Note on the Individual and His Status in Indian Thought". Philosophy East and West. University of Hawai'i Press. 2 (3): 254–258. doi:10.2307/1397274. JSTOR 1397274.

- ↑ Franklin Edgerton (1952). The Bhagavad Gita, Part 2. Harvard University Press. pp. 91–92.

- ↑ Jonardon Ganeri (2007). The Concealed Art of the Soul: Theories of Self and Practices of Truth in Indian Ethics and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 68–70. ISBN 978-0-19-920241-6.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Christopher G. Framarin (2006). "The Desire You Are Required to Get Rid of: A Functionalist Analysis of Desire in the Bhagavadgītā". Philosophy East and West. University of Hawai'i Press. 56 (4): 604–617. doi:10.1353/pew.2006.0051. JSTOR 4488055. S2CID 170907654.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 Arthur Llewellyn Basham (1991). The Origins and Development of Classical Hinduism. Oxford University Press. pp. 86–87. ISBN 978-0-19-507349-2.

- ↑ White, David (1971). "Human Perfection in the Bhagavadgita". Philosophy East and West. University of Hawai'i Press. 21 (1): 43–53. doi:10.2307/1397763. JSTOR 1397763.

- ↑ M.V. Nadkarni 2016, pp. 82, 95–96

- ↑ Franklin Edgerton (1952). The Bhagavad Gita, Part 2. Harvard University Press. pp. 47–48, 73–74, 83–84.

- ↑ Minor 1986, pp. 38–39, 123–128, 143.

- ↑ Gavin Flood (2004). The Ascetic Self: Subjectivity, Memory and Tradition. Cambridge University Press. pp. 83–84 with notes. ISBN 978-0-521-60401-7.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Sargeant 2009, p. xii.

- ↑ Robinson 2006, pp. 92–93, 133–134.

- ↑ Upadhyaya 1998, pp. 474–475.

- ↑ Hiltebeitel 2002.

- ↑ Scheepers 2000, pp. 122-127.

- ↑ Galvin Flood; Charles Martin (2013). The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation. W.W. Norton & Company. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-0-393-34513-1.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Fowler 2012, pp. xxi–xxii.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 M.V. Nadkarni 2016, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Friedrich Otto Schrader (1908). A descriptive catalogue of the Sanskrit manuscripts in the Adyar Library. Adyar Library Oriental Pub. p. 57.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedminor1982lli - ↑ Gambhirananda 1997, p. xvii.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Minor 1982, pp. l–li.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Minor 1982, pp. l–ii.

- ↑ Wilkins, Charles, ed. (1785). The Bhagavat-Geeta, Or, Dialogues of Krishna and Arjoon in Eighteen Lectures with notes. LONDON.

- ↑ Garrett, John; Wilhelm, Humboldt, eds. (1849). The Bhagavat-Geeta, Or, Dialogues of Krishna and Arjoon in Eighteen Lectures. Bangalore: Wesleyan Mission Press. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 99.4 Gerald James Larson (1981), "The Song Celestial: Two centuries of the Bhagavad Gita in English", Philosophy East and West, University of Hawai'i Press, 31 (4): 513–40, doi:10.2307/1398797, JSTOR 1398797

- ↑ Sargeant 2009, p. 1.

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 154–155.

- ↑ George Thompson (2008). The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 978-1-4668-3531-3.

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 159–161.

- ↑ Sargeant 2009, p. xxv.

- ↑ Miller 1986, pp. 14–17

- ↑ Bloom 1995, p. 531

- ↑ Doniger, Wendy (August 1993), "Obituary: Barbara Stoler Miller", Journal of Asian Studies, 52 (3): 813–15, doi:10.1017/S002191180003789X, JSTOR 2058944

- ↑ Arvind Sharma (2014), Review: Three New Books on the "Bhagavad Gītā", International Journal of Hindu Studies, Vol. 18, No. 2, p. 269

- ↑ Galvin Flood; Charles Martin (2013). The Bhagavad Gita: A New Translation. W.W. Norton & Company. p. xii. ISBN 978-0-393-34513-1.

- ↑ W.J. Johnson (2004). The Bhagavad Gita. Oxford University Press. pp. vii–ix. ISBN 978-0-19-283581-9.

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 80–81.

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ W.J. Johnson (2004). The Bhagavad Gita. Oxford University Press. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 978-0-19-283581-9.

- ↑ Sharma 1986, pp. xvi–xxvii.

- ↑ "Review: 'The Teachings of Bhagavad Gita' by Richa Tilokani". Times of India. Times of India. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ Minor 1982, pp. xx–xxi.

- ↑ Vassie, R. (1988). Persian interpretations of the Bhagavadgita in the Mughal period : with special reference to the Sufi version of #Abd al-Raham Chishti (Ph.D. thesis). School of Oriental and African Studies (University of London).

- ↑ What had previously been known of Indian literature in Germany had been translated from the English. Winternitz 1972, p. 15

- ↑ J.A.B. van Buitenen 2013, p. xii; Emile Senart's Translation: Wikisource.

- ↑ Rawat, Virendra Singh (8 September 2015). "After selling 580 mn books, Gita Press faces labour crisis". Business Standard. Retrieved 12 October 2019.

- ↑ Bhagavadgita, Chennai, India: Bharati Publications, 1997

- ↑ A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada; et al. (2015). "Bhagavad Gita As It Is" (PDF). Bhaktivedanta Book Trust (1972 edition).

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 123.2 123.3 123.4 123.5 Davis 2014, pp. 167–168, 175

- ↑ Jones & Ryan 2007, p. 199

- ↑ "F.A.T.E. – the First American Theistic Exibition – Back To Godhead". Back to Godhead. 12 (7): 16–23. 1 July 1977. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Nadkarni, M.V. (2016). The Bhagavad-Gita for the Modern Reader: History, Interpretations and Philosophy. Taylor & Francis. pp. 135–137. ISBN 978-1-315-43899-3.

- ↑ 127.0 127.1 127.2 127.3 127.4 127.5 127.6 127.7 127.8 SGS Sadhale ( 1935), The Bhagavad Gita with Eleven Commentaries, Volume 1 & 2, pages 1–7

- ↑ Singh 2006, pp. 54–55

- ↑ Davis 2014, pp. 55–56.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 Dnyandev; Pradhan, Vitthal Ganesh (1987), Lambert, Hester Marjorie (ed.), Dnyaneshwari : Bhāvārthadipikā, State University of New York Press, pp. x–xi, ISBN 978-0-88706-487-6

- ↑ Eliot Deutsch & Rohit Dalvi 2004, p. 60.

- ↑ Flood 1996, p. 124.

- ↑ Abhinavagupta (Rājānaka.); Arvind Sharma (Translator, Reviewer) (1983). Gītārthasaṅgraha. Brill Academic. pp. 30–31 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-06736-1.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ↑ 134.0 134.1 Zaehner 1969, p. 3

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 135.2 Flood 1996, p. 124

- ↑ Alladi Mahadeva Sastry (1980). The Bhagavad Gita with the Commentary of Sri Sankaracharya. Samata.

- ↑ Alladi Mahadeva Sastry (1980). The Bhagavad Gita with the Commentary of Sri Sankaracharya. Samata. pp. ii, 1–6.

- ↑ N.V. Isaeva (1993). Shankara and Indian Philosophy. State University of New York Press. pp. 211–214. ISBN 978-0-7914-1282-4.

- ↑ Abhinavagupta (Rājānaka.); Arvind Sharma (Translator, Reviewer) (1983). Gītārthasaṅgraha. Brill Academic. pp. 30–35, 41–47 with footnotes. ISBN 90-04-06736-1.

{{cite book}}:|author2=has generic name (help) - ↑ Sampatkumaran 1985, p. xx

- ↑ William M. Indich (1995). Consciousness in Advaita Vedanta. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 1–2, 97–102. ISBN 978-81-208-1251-2.

- ↑ C.J. Bartley (2013). The Theology of Rāmānuja: Realism and Religion. Routledge. pp. 2–3, 87–91. ISBN 978-1-136-85306-7.

- ↑ Sargeant 2009, pp. xxiii–xxiv.

- ↑ Rao 2002, p. 86

- ↑ 145.0 145.1 145.2 145.3 M.V. Nadkarni 2016, pp. 37–38

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 SGS Sadhale ( 1936), The Bhagavad Gita with Eleven Commentaries, Volume 2 of 3

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Edwin Bryant; Maria Ekstrand (2004). The Hare Krishna Movement: The Postcharismatic Fate of a Religious Transplant. Columbia University Press. pp. 175–176. ISBN 978-0-231-50843-8.

- ↑ Singh 2006, p. 55

- ↑ W. Doderet (1926), ]https://www.jstor.org/stable/607401 The Passive Voice of the Jnanesvari], Bulletin of the School of Oriental Studies, Cambridge University Press, Vol. 4, No. 1 (1926), pp. 59–64

- ↑ Gyaānadeva & Pradhan 1987

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 D.C. Sircar (1996). Indian Epigraphy. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-81-208-1166-9.

- ↑ R.D. Ranade (1997). Tukaram. State University of New York Press. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-1-4384-1687-8.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton (2011). Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations. ABC-CLIO. pp. 373–374. ISBN 978-1-59884-206-7.

- ↑ Dnyandev; Pradhan, Vitthal Ganesh (1987), Lambert, Hester Marjorie (ed.), Dnyaneshwari : Bhāvārthadipikā, State University of New York Press, p. xviii with footnote 1, ISBN 978-0-88706-487-6

- ↑ Karine Schomer; W.H. McLeod (1987). The Sants: Studies in a Devotional Tradition of India. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 219–223. ISBN 978-81-208-0277-3.

- ↑ Christian Novetzke (2005). Guy L. Beck (ed.). Alternative Krishnas: Regional and Vernacular Variations on a Hindu Deity. State University of New York Press. pp. 113–118. ISBN 978-0-7914-6415-1.

- ↑ Sharma 2000, p. 266.

- ↑ Sharma 2000, p. 391.

- ↑ For Aurobindo, Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, and Chinmayananda as notable commentators see: Sargeant 2009, p. xix

- ↑ For Aurobindo as notable commentators, see: Gambhirananda 1997, p. xix

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert W., "Tilak and the Bhagavadgita's Doctrine of Karmayoga", in: Minor 1986, p. 44

- ↑ Stevenson, Robert W., "Tilak and the Bhagavadgita's Doctrine of Karmayoga", in: Minor 1986, p. 49

- ↑ 163.0 163.1 Jordens, J.T.F., "Gandhi and the Bhagavadgita", in: Minor 1986, p. 88

- ↑ Gandhi 2009, First Edition 1946. Other editions: 1948, 1951, 1956.

- ↑ A shorter edition, omitting the bulk of Desai's additional commentary, has been published as: Anasaktiyoga: The Gospel of Selfless Action. Jim Rankin, editor. The author is listed as M.K. Gandhi; Mahadev Desai, translator. (Dry Bones Press, San Francisco, 1998) ISBN 1-883938-47-3.

- ↑ Sargeant 2009, pp. xxiv–xxvi.