Vedic religion in Ancient Tamilakam

Thank you for being part of the Bharatpedia family! 0% transparency: ₹0 raised out of ₹100,000 (0 supporter) |

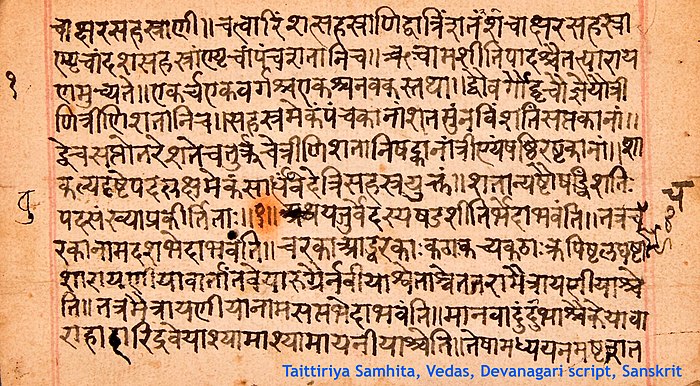

Vedic religion in Ancient Tamilakam finds its earliest literary mention in the Sangam literature dated to the 5th century BCE. The Vedas were read by almost every caste in ancient Tamil Nadu. Vedic Religion is a major part of Hinduism and also called as Early Hinduism. The Vedas (IAST: veda, Tamil: வேதம் Sanskrit: वेदः, lit. 'knowledge') are a large body of religious texts originated in ancient India around c. 1500–1200 BCE[7][note 1] Composed in Vedic Sanskrit, the texts constitute the oldest layer of Sanskrit literature and the oldest scriptures of Hinduism.[13][14][15] An Indian historian, archaeologist and epigraphist named Ramachandran Nagaswamy mentions that Tamil Nadu was a land of Vedas and a place where everyone knew the Vedas.[16] The Vedas are also considered as a text filled with deep meaning which can be understood only by scholars.[17] The Purananuru mentions that the ancestors of Velir kings where born from the Sacred fire of a Northern sage[18] and the Paṭṭiṉappālai mentions that the four Vedas were chanted by the priests of Ancient Tamilakam, [19] this shows chanting of Vedas and growing sacred fires are part of the Tamil culture. There were many separate temples built for teaching the Vedas, Upanishads, and sutras by various kings of various periods, one of the best examples is the Vardharajaperumal temple located at Thirubuvanai. An inscription of the temple dated to the 30th regnal year of Rajadhiraja I (c. 1048 CE), mentions teaching Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Chandogasama, Talavakrasama, Apurva, Vajnasaneya, Bodhayaniya Sathashatandha Sutra and explanations of sastras and epics like Ramayana .[20] There are many other temples like Parthasarathy temple, Parthivapuram, Vaikunda Perumal Temple, Uthiramerur, Kattu Narasimhaperumal Temple, Srirangam, Brihadisvara Temple, and many Mutts like Kanchi Kamakoti Peetham, Ahobila Matha.

Mentions in Sangam Literature[edit]

Tolkāppiyam[edit]

Tolkāppiyam (Tamil: தொல்காப்பியம்[21]) is the most ancient extant Tamil grammar text and the oldest extant long work of Tamil literature.[22][23] The word Tolkāppiyam is an attribute-based composite word with 2 words of 2 different languages, with tol meaning "ancient" in Tamil, and kappiyam derived from a Sanskrit word Kāvya which means "book, text, poem"; together, the title has been translated as "ancient book",[24] "ancient poem",[25] or "old poem".[26] The word 'kappiyam' is from the Sanskrit word Kāvya.[27] According to Kamil Zvelebil, the earliest sutras of the Tolkappiyam were composed by author(s) who lived before the "majority of extant" Sangam literature, who clearly knew Pāṇini and followed Patanjali works on Sanskrit grammar because some verses of Tolkappiyam – such as T-Col 419 andT-Elutt 83 – seem to be borrowed and exact translation of verses of Patanjali's Mahābhāṣya and ideas credited to more ancient Pāṇini. Further, the author(s) lived after Patanjali, because various sections of Tolkappiyam show the same ideas for grammatically structuring a language and it uses borrowed Indo-European words found in Panini and Patanjali works to explain its ideas.[28] According to Hartmut Scharfe and other scholars, the phonetic and phonemic sections of the Tolkappiyam shows considerable influence of Vedic Pratishakhyas, while its rules for nominal compounds follow those in Patanjali's Mahabhashya, though there is also evidence of innovations. The author(s) had access and expertise of the ancient Sanskrit works on grammar and language.[29] The literary theory of Tolkappiyam, according to Peter Scharf, borrows from Sanskrit literary theory texts.[30] The phonetic and phonemic sections of the first book show the influence of Vedic Pratisakhyas, states Hartmut Scharfe, but with some differences. For example, unlike the Pratisakhyas and the later Tamil, the first book of Tolkappiyam does not treat /ṭ/ and /ṇ/ as retroflex.[31] According to Peter Scharf, the sutras here are inspired by the work on Sanskrit grammar by Panini, but it uses Tamil terminology and adds technical innovations which shows that the author must have learned Sanskrit too.[30] Verb forms and the classification of nominal compounds in the second book show the influence of Patanjali's Mahabhashya.[31] The author of Tolkāppiyam mentions the Rigvedic deities in his book who as Maha Vishnu, Skandha, Indra, Varuna and Durga or Lakshmi.[32]

Texts which explain Vedic Practices and Vedic Mythology[edit]

Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai[edit]

Perumpāṇāṟṟuppaṭai (Tamil: பெரும்பாணாற்றுப்படை) is an ancient Tamil poem in the Pattuppattu anthology of the Sangam literature.[37] It contains 500 lines in the akaval meter.[38] It is one of five arruppatai genre poems and was a guide to other bards seeking a patron for their art. Set as a praise for chieftain Tonataiman Ilantiraiyan of the Kanchi territory, it was composed by Uruttirankannanar sometime around 100–200 CE. The poem has several mentions of Vedas and brahmins of the village in Kanchipuram. The poem mentions a yupa post (a form of Vedic altar) in the Brahmin village.[1] Vedas are recited by these Brahmins, and even their parrots are mentioned in the poem as those who sing the Vedic hymns. People in these Vedic villages did not eat meat, nor raise fowls. They ate rice, salad leaves boiled in ghee, pickles and vegetables.[39] Elsewhere, the hunters are described as meat-eaters, herdsmen relied on milk, yoghurt and ghee, fishermen ate a variety of fish, while farmers ate beans, fruits and farm produce. Rice was a staple in all landscapes.[40] Rice was also a major part of any offerings to the gods in temples and on festivals, according to several lines in the poem, such as over lines 267–269.[41] Various Vedic rituals were practised by the people of Tamilakam. The Text mentions the Thiruvekka Sonavanam seiytha Perumal Temple dedicated to Maha Vishnu who is in a Reclining posture.[42] The Vedic mythology of Lord Brahma born from Maha Vishnu's navel is explained. The King Ilandiraiyan is considered to born from the Vedic god Brahma which explains the concept of the Mind born sons of Brahma followed even in Ancient Tamilakam.[42][43][44] the poem mentions Rishis, who perform Vedic and yogic rights, Brahmins and many others reciting the Vedas, Rishis performing tapas and various Vedic sacrifices.[34] Worship of Skandha or Lord Murugan is found in several texts of sangam literature and is worshiped as per the Vedas. There are ancient references which can be interpreted to be Kartikeya in the Vedic texts, in the works of Pāṇini (~500 BCE), in the Mahabhasya of Patanjali and in Kautilya's Arthashastra.[45] For example, the term Kumara appears in hymn 5,2 of the Rig Veda.[46][note 2] The Kumara (Familiar name of Murugan) of verse 5.2.1 can be interpreted as Skanda, or just any "boy". However, the rest of the verses depict the "boy" as bright-colored, hurling weapons and other motifs that later have been associated with Skanda.[47]

The Skanda-like motifs found in Rig Veda are found in other Vedic texts, such as section 6.1-3 of the Shatapatha Brahmana.[48] In these, the mythology is very different for Kumara, as Agni is described to be the Kumara whose mother is Ushas (goddess Dawn) and whose father is Purusha.[46] The section 10.1 of the Taittiriya Aranyaka mentions Sanmukha (six faced one), while the Baudhayana Dharmasutra mentions a householder's rite of passage that involves prayers to Skanda with his brother Ganapati (Ganesha) together.[49][note 3]

Purananuru[edit]

Purananuru (Tamil: புறநானூறு, Puṟanāṉūṟu ?, is a classical Tamil poetic work and traditionally the last of the Eight Anthologies (Ettuthokai) in the Sangam literature.[51] Purananuru mentions several Vedic rituals and practices practised by kings and people of ancient Tamilakam. The text dedicates invocatory poem to Lord Shiva which mentions the Brahmins reciting the Vedas to please Lord Shiva. The Purananuru poems also use words, phrases, and metaphors, including references to the Himalayas of "immeasurable heights", Maha Vishnu, Mahalakshmi, Balarama, The Four Vedas known as Rig, Yajur, Sama, and Atharvana, the Ramayana, various rivers, and other aspects.[52][53][54] The earliest reference to the Epic Ramayana in Tamil literature is found in the Purananuru 378, attributed to the poet UnPodiPasunKudaiyar, written in praise of the Chola king IIamchetchenni. The poem makes the analogy of a poet receiving royal gifts and that worn by the relatives of the poet, to the event in the Ramayana, where Sita the Wife of The invincible (unconquerable) Rama, drops her jewels when abducted by the Demon King Ravana and these jewels being picked up red-faced monkeys who delightfully wore the ornaments.[53][54] Purananuru mentions several kings doing several Vedic sacrifices, Poem 9 and 15 written by poet Nettimaiyār' sings the greatnes of Palyākasālai Muthukudumi Peruvazhuthi who performed several Vedic practises like Anthima Samskaram for poor people and performing Vedic sacrifices like Yagyam or Homam and planting Yupa sthambam [55][56][57] The poet questions the King in the Poem 15, "Which of these is greater in number" the number of victory flags planted or the number of Yupa sthamba planted after performing many sacrifices (Yagam) prescribed by the Four Vedas and the books of ritual (Śrauta shastras), fine sacrifices of an excellence that will not die away and charged with a fame that is difficult to achieve, oblations that rose rich in ghee and all the other elements of the sacrifice? For you, which is greater, O greatness! The king is named as Palyākasālai Muthukudumi Peruvazhuthi Pandiyan and he got his epithet name Palyākasālai because he performed several Yagams (Vedic Sacrifice).[58][59] Another important king is Rāsasooyam Vētta Perunarkilli Chozhan, a Chozha king who performed the Rajasooya yagyam.[60]

Purananuru poem 166, mentions a Brahmin king Poonchātrūr Pārpān Kouniyan Vinnanthāyan Who performs all the 21 Vedic Rituals and wearing a Sacred thread (Yagnopaveetham also referred to as Poonal[61], Janeu, Jandhyam, Munja, Janivara and Yonya) over his shoulders and dose so many Vedic sacrifices.[62][63]

You who are descended from men renowned

for their superb learning, men who

performed to perfection all twenty-one

kinds of sacrifice, who confirmed

the truth, never thinking it false,

who understood lies that resembled truth,

thus defeating those who would contend

with the one ancient work of six sections (Sastras)

and four divisions (Vedas), focused on Righteousness,

never swerving from the well-chosen words

of the Primal Being with his long, matted hair!

You glow in your black antelope skin

from dry forest land, needed for the ritual,

worn over the Thread around your shoulder!

Your beloved wives, worthy of your high

station, flawlessly faithful, free of harshness,

renowned for their virtue, donning the sacred ornaments,

their foreheads small, their hips and thighs large and wide,

of few words and rich abundant hair, request their ritual responsibilities!

Whether in settled land or jungle, omitting

none of the fourteen sites, you pour out

more ghee than there is water, sacrifice

more times than there are numbers, spread

your fame wider than the earth, and at

the great moment when a difficult sacrifice is completed,

may we always see you in your high and perfect state, offering hospitality!

Purananuru poem 166 translated by George L. Hart

[64]

Purananuru mentions 21 rituals in the poem 166, which is explained in the Vedas in detail, the Vedas split the 21 Rituals (Yagams) into 3 main Yagams with 7 Yagams within each of the 3 Main Yagams.

The Kalpa Sutras list the following Yagams types:[65] 1st main Yagam is the Pāka-Yagams: — Aṣtaka, sthālipāka, parvana, srāvaṇi, āgrahayani, caitri, and āsvīyuji. These Yagams involve consecrating cooked items. These Yagams are the first 7 Yagams.

2nd Main Yagam is the Soma-Yagams: — Agnistoma, atyajnistoma, uktya, shodasi, vājapeya, atirātra, and aptoryama are the seven soma-Yagams. These Yagams are the next 7 Yagams.

3rd main Yagam is the Havir-Yagams: — Agniyādhāna, agnihotra, darśa-pūrṇamāsa, āgrayana, cāturmāsya, niruudha paśu bandha,[66] sautrāmaṇi. These involve offering havis or oblations. These are the last 7 Yagams.

All these 3 main yagams of 7 each together make 21. Purananuru poem 224 written by the well known poet Avvaiyar also mentions about the 3 main fires.Avvaiyar compares the King Rāsasooyam Vētta Perunarkilli Chozhan's beauty with the 3 main fires which are performed by the Twice-born Brahmins.[67]

Paṭṭiṉappālai[edit]

Paṭṭiṉappālai (Tamil: பட்டினப் பாலை) is a Tamil poem in the ancient Sangam literature.[68] There are mentions of the Rigvedic deities like Varuna worshiped as sea god by fishermen and Mahalakshmi painted on the fort walls, She is called as the good and worthy goddess who protects the city from Evil and Moodevi.[33] The text claims that the people and the priest perform the Vedic duties which were given by the gods. They tend care for the Bulls and cows and the priests of the city chant the four Vedas.[33] Words like amaras, avuthi and nanmariyor refer to Gods, Yagam and Priests who chant the Four Vedas with a pig tail or a "hermits with matted lock". The Priests offer cooked and uncooked food to the guests who come for the Vedic Sacrifice and They always speak the truth and deem it shame To lie.[19] People of the city worships gods in the form of pillars (Likely considered to be Lord Vishnu)[69][70] the text mentions, worship of Maha Vishnu, Mahalakshmi and Skandha.[71][72][73] Skandha was worshiped as the red god and the god of war.[74]

Maturaikkāñci[edit]

Maturaikkāñci (Tamil: மதுரைக் காஞ்சி), [75] is an ancient Tamil poem in the Sangam literature.[76] It is a didactic poem and its title connotes the "poetic counsel addressed to the king of Madurai".[77]

The text mentions that the people Take bath on Krishna Paksha Sapthami to clean their sins, The Vedas were chanted by the priests and they follow the prescribed rights correctly as per the Vedas. The priest performed Yajna and other Karmas for the peoples wellness. The author of the text also tells the Pandyan King to relies the some Vedic principles like the unity of soul and universe.[78] It also mentions the ability of Rishis to leave their body and the soul reaching heaven during the process of Yoga which is called as Jivan muktas.[78] The people of thcity believied in superstions and Vampieres or ghosts roaming at midnight in the streets.[78] People Worshiped Vishnu, Shiva, Lakshmi and Muruga.[79] There are mentions of a Pandiyan king named Mutukudumi performing Vedic Sacrifices and Sacrificial rights which gives him praises and learning Truths (Dharma) from Sages.[80] According to J. V. Chelliah The verse "holy practises that teach like Nediyon"[80] refer to the Bhagavath Gita taught by Krishna (Nediyon is a name dedicated to Lord Vishnu[81]).[82] The Pandyan king also gets a name "Palyagasalay" which means the king who performed several Yagams (Vedic Sacrifices).[82]

Silappatikaram[edit]

Silappatikaram, Which is the earliest Tamil epic mentions Kannagi and Kovalan marry according to the Vedas and go around the ceremonial fire and perform the Holy rights as per the Vedas and sutras with a priest completing the holy wedding rites.[5][83] Lines 1.27–29 of the epic introduces Kannagi with allusions to the Rig Vedic Deity Mahalakshmi and the Vedic mythology of Samudra Mathan.[84] Where as kovalan is introduced as the god of love himself, the incomparable Skanda".[5]

"She is Lakshmi herself, goddess of peerless beauty that rose from the lotus, and chaste as the immaculate Arundhati".[84]

The Tamil epic has many references and allusions to the Sanskrit epics and puranic legends. For example, it describes the fate of Poompuhar suffering the same agony as experienced by Ayodhya when Rama leaves for exile to the forest as instructed by his father.[85] The Aycciyarkuravai section (canto 27), makes mention of the Lord who could measure the three worlds, going to the forest with his brother, waging a war against Lanka and destroying it with fire.[85] These references indicate that the Ramayana was known to the Cilappatikaram audience many centuries before the Kamba Ramayanam of the 12 Century CE.[85]

According to Zvelebil, the Cilappatikaram mentions the Mahabharata and calls it the "great war", just like the story was familiar to the Sangam era poets too as evidenced in Puram 2 and Akam 233.[86] One of the poets is nicknamed as "The Peruntevanar who sang the Bharatam [Mahabharatam]", once again confirming that the Tamil poets by the time Cilappatikaram was composed were intimately aware of the Sanskrit epics, the literary structure and significance of Mahakavyas genre.[87]

There mentions of 2 great Vaishnavite temples dedicated to Lord Vishnu. One is Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam and other one is Venkateswara Temple, Tirumala which are the most famous South Indian temples of Lord Vishnu.[88][89]

Mention of Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam:- Silapadikaram (book 11, lines 35–40):[88]

Tamil

ஆயிரம் விரித்தெழு தலையுடை அருந்திறற் பாயற் பள்ளிப் பலர்தொழு தேத்த விரிதிரைக் காவிரி வியன்பெருந் துருத்தித் திருவமர் மார்பன் கிடந்த வண்ணமும்

Transliteration

āyiram viritteḻu talaiyuṭai aruntiṟaṟ pāyaṟ paḷḷip palartoḻu tētta viritiraik kāviri viyaṉperu turuttit tiruvamar mārpaṉ kiṭanta vaṇṇamum

On a magnificent cot having a thousand heads spread out, worshipped and praised by many, in an islet surrounded by Kaveri with billowing waves, is the lying posture of the one who has Lakshmi sitting in his chest.[88]

Mention of Venkateswara Temple, TirumalaSilappatikaram, Kāṭukāṇ kātai: 41–51

Translation

vīṅkunī raruvi vēṅkaṭa meṉṉum ōṅkuyar malaiyat tucci mīmicai virikatir ñāyiṟun tiṅkaḷum viḷaṅki irumaruṅ kōṅkiya iṭainilait tāṉattu miṉṉukkōṭi yuṭuttu viḷaṅkuviṟ pūṇṭu naṉṉiṟa mēkam niṉṟatu pōlap pakaiyaṇaṅ kāḻiyum pālveṇ caṅkamum takaipeṟu tāmaraik kaiyi ṉēnti nalaṅkiḷar āram mārpiṟ pūṇṭu polampū vāṭaiyiṟ polintu tōṉṟiya ceṅkaṇ neṭiyōṉ niṉṟa vaṇṇamum.[90]

Meaning

(I also came to see) the beauty of the red-eyed Lord, holding in His beautiful lotus-hands the discus which is death to His enemies, and also the milk-white conch; (to see Him) wearing a garland of tender flowers on His chest, and draped in golden flowers; and dwelling on the topmost crest of the tall and lofty hill named vēṅkaṭam.[90]

Netiyon is another name dedicated to Maha Vishnu in Ancient Tamilakam.[81] ceṅkaṇ neṭiyōṉ means “Red-eyed Vishnu” and Vēṅkaṭam refers to Venkateswara Temple, Tirumala. Maha Vishnu is being referenced as the Red eyed lord even in the sacred book Vishnu Sahasranama which is featured in the Anushasana Parva of Mahabharatha.[91][92] Which shows that Ilango Adigal and Ancient Tamils were aware of the Vishnu Sahasranama which is much older than the Silappatikaram.[91]

There are several other mentions of Various gods like Maha Vishnu, Mahalakshmi, Skanda, Shiva, Uma, Rama, Krishna, Balarama, Jayanta, Brahma, Indra, Kamadeva, Rati, Arundhathi, Rohini, Chandra, Agastya, Narada and many more gods. There mentions of Mahabharatha, Ramayana, and Various Puranas.

Manimekalai[edit]

Maṇimēkalai (Tamil: மணிமேகலை, lit. 'jewelled belt, girdle of gems'), also spelled Manimekhalai or Manimekalai, is a Tamil epic[93] composed by Kulavāṇikaṉ Seethalai Sataṉar probably somewhere between the 2nd century.[94]The epic has several references to Vedic practices and Puranas all around Tamilakam and other parts of India. Manimekalai's beauty is rivaled that of the goddess of fortune, Mahalakshmi.[95] The Canto 1 starts with a festival in the chola city Dedicated to Indra. [96] Later Canto 3 mentions "Kalamukhas (a subtradition of Shaivism) wearing oleander flower garlands and Rudraksha mala, body smeared with ashes, acting madly".[97] Sudhamati (Friend of Manimekalai) describes she is from Bengal, her father who is a Brahmin named Kaushika who performs Vedic Sacrifices, and they came to the south on a [Hindu] pilgrimage towards Kanyakumari. Kanyakumari is one of the sacred places in Tamil Nadu which is mentioned in the Upanishads of the Vedas. Devi Kanya Kumari has been mentioned in Ramayana, Mahabharata, and the Sangam works Manimekalai, Purananuru and the Mahanarayana Upanishad, a Vaishnava Upanishad in the Taittiriya Samhita of Krishna Krishna Yajur Veda.[98] She related her journey to the journey of Rama in the Ramayana.[95] The epic talks abought a Vessel called "cow of abundence" They mention the story of first possessor Aputra. The canto starts with a Brahmin named Abhanjika Kassi (Hindu holy city) who taught the Vedas.[99] It explains customs like ladies who are pregnant should not take a dip in oceans or holy rivers. The Text mentions the Upanayana ceremony (Sacred thread ceremony) done by Brahmins and teaching of Vedas.[99] It mentions that Aputra who is a Brahimin fights against a set of Brahmins who performs animal sacrifices and tells them "You Brahmins Know the Vedas properly, heed my words and forgo any action which makes other living beings suffer. The other brahmins says do not twist the meaning of Vedas which were born from the mouth of Brahma who emerged from the navel of Lord Vishnu. Vishnu the Great god who has Chakra as his weapon.[99] Aputra mentioned a list of Rishis who were born from animals and said these Rishis too gave you the Veda mantras. Aputra also mentions that the vedas do not see birth of Human.[99] These lines show that Some Vedic Practitioners were Vegetarians[100] were as some were Non Vegetarians.[101] However many other sangam texts shows that Brahmins of south India followed Vegetarianism.[39]

Texts which explain Vedic Mythology and Vedic principals[edit]

Paripāṭal[edit]

The Paripādal (Tamil: பரிபாடல், meaning the paripadal-metre anthology) is a classical Tamil poetic work and traditionally the fifth of the Eight Anthologies (Ettuthokai) in the Sangam literature.[102] Kamil Zvelebil states that the hymns dedicated to Lord Vishnu and Lord Skandha has branded the paripadal as a Sanskrit plagiat within the so-called Sangam texts.[103] Paripāṭal explains several concepts of the Vedas, Vedanta and many Puranic stories (Especially Vishnu and Skanda).[17] It explains the brahmins chanting the vedas in which Vishnu is the great god mentioned in the Vedas.[104] The text also explains conceptes of Chaturvyuhas mentioned in the Viṣṇudharmottara purāṇa, and can be interpreted as an architectural representation of the Caturvyuha concept and the Pancaratra doctrine, centering on the depictions of the four main emanations of Vishnu: Vāsudeva, Samkarshana, Pradyumna and Aniruddha.[105] According to Lubotsky, it is likely that the entrance is dedicated to the Vāsudeva aspect of Vishnu; the Anantashayana side is his role as the creator (Aniruddha); the sage form of Nara-Narayana side symbolizes his preservation and maintainer role in cosmic existence (Pradyumna); and the Gajendramoksha side represents his role as the destroyer (Samkarsana).[105]

Translation

செங்கண் காரி! கருங்கண் வெள்ளை! பொன்கண் பச்சை! பைங்கண் மாஅல்!

Meaning

[106]

O Vasudeven with red eyes and black complexion! O Sangarudanan with black eyes and white complexion! O Prathyumnan of red golden hue! O Aniruthan of green complexion!

Paripāṭal also explains various legends of Vishnu Like Narasimha and Varaha which were mentioned in the Vedas way earlier. The Legend of Varaha is stated in the Taittiriya Aranyaka. The Taittiriya Aranyaka (10.1.8) states the earth is lifted by a "black boar with hundred arms".[107] The Taittiriya Brahmana (1.1.3.6) expands the Taittiriya Samhita narrative.[108][109][109] The "Lord of creation" was pondering on how the universe should be. He saw a lotus leaf and took the form of a boar to explore under it. He found mud and outstretched it on the leaf, rising above the waters. It was called the earth – Bhumi, literally "that which became (spread)".[107][110] and The legend of Narasimha which are found in the Vedic texts like Vajaseneyi Samhita 10.34, Pancavimsa Brahmana 12.6.8 and Taittiriya Brahmana 1.7.1.6.,[111] is also found in the Paripāṭal poem 4 verse 10 to 21.[106][111]

Legend of Narasimha according to Paripāṭal

O Lord with faultless red eyes! With

burning hatred in his heart and drying up the

sandal paste on his chest, Hiranyan the evil king

tortured his son Prahalathan for singing your

praises, inflicting on him great sorrow. The young

man was not disrespectful to his father who deserved

disrespect. You embraced Prahalathan’s fine chest

because of your love for him. You attacked and ruined

Hiranyan with great strength, leaping upon his

mountain-like chest as drums roared like thunder.

You tore him apart with your split claws and scattered

his flesh, along with broken pieces of pillar which you

split and came out, in your Narasimhan form.

Paripāṭal, poem 4, Verses 10 - 21[106]

Mullaippāṭṭu[edit]

Mullaippāṭṭu Tamil: முல்லைப்பாட்டு is an ancient Tamil poem in the Sangam literature likely dated around 230 CE.[114][115] The first 7 lines of the Mullaippāṭṭu explains the Vamana Avataram of Maha Vishnu as mentioned in the Rig Veda, Book 1, Hymn 22, Verses 16–18.[116] Lines 46–47 of Mullaippattu mentions to Vaishnava Brahmin yogis in ochre-colored clothes carrying three staves (Tridanda) and chanting the Vedas who were prominent during the period .[117][118] There many other mentions of Vamana even other texts of Sangam literature[119] and other Vedas.[120]

First 7 lines which explain Vamana measuring this world.

It's a short and a gloomy eve. The showers fall

From the clouds that travel fast with water drunk

from the cold, resounding sea, and rise from hills

With a turn to the right, as Maha Vishnu- he who bears

In mighty hands the disc and right-whorled chank

and Lakshmi clasps-once measured universes expanse

And rose with water dripping from his hands.– JV Chelliah: Mullaippāṭṭu 1 – 7 [121]

Tirumurukāṟṟuppaṭai[edit]

Tirumurukātṟuppadai (Tamil: திருமுருகாற்றுப்படை, meaning Guide to Lord Murugan) is an ancient intensely devotional Tamil poem in the Sangam literature genre entirely dedicated to the god Murugan. Murugan is described as the nephew of the god Vishnu, who is called Mayon or the ruler of the worlds.[122] Authored by Nakkiranar, it is the first poem in the Ten Idylls (Pattuppāṭṭu) anthology.[122] The poem is generally dated to the late classical period (2nd to 4th century CE),[123] with some scholars suggesting it may have been composed a few centuries later.[124]

The Tirumurukarruppatai has 312 akaval meter verses, states Zvelebil.[125] According to Francis, the critical editor has 317 verses.[126] It describes the beauty and the warrior nature of Murugan, six sacred shrine regions of Murugan, legends such as the killing of Surapadma, his six faces and the twelve arms along with their functions. The Hindu god is described as a gentle erotic lover of goddesses as well as a gruesome bloody warrior on the battlefield.[125][126] This elaboration includes 30 verses on the beauty of every body part of heavenly maidens.[127] Metaphors refer to Indra, kantal flowers, emerald sea and others to paint "magnificent natural scenes", states Zvelebil. The poem highlights the peacock and his war banner flag. Both his first wife Deyvayanai – the daughter of the Vedic god of rain, thunder and war Indra, and his second wife Valli – the daughter of a hunter, are included in the poem. It also mentions the Vedas and has numerous loanwords from the classical Sanskrit literature.[128]

Thirukkuṟaḷ[edit]

The Tirukkuṟaḷ (Tamil: திருக்குறள், lit. 'sacred verses'), is a classic Tamil language text consisting of 1,330 short couplets, or kurals, of seven words each.[130] The text is divided into three books with aphoristic teachings on virtue (aram), wealth (porul) and love (inbam), respectively.[131][132][133] Considered one of the greatest works ever written on ethics and morality, it is widely acknowledged for its universality and secular nature.[134][135] Its authorship is traditionally attributed to Valluvar, also known in full as Thiruvalluvar. The text has been dated variously from 300 BCE to 5th century CE. The traditional accounts describe it as the last work of the third Sangam, but linguistic analysis suggests a later date of 450 to 500 CE and that it was composed after the Sangam period.[136]

According to Many scholars, Valluvar's writings suggest that he belonged to Hinduism. Hindu teachers have mapped his teachings in Tirukkuṟaḷ to the teachings found in Hindu texts.[137] Valluvar's treatment of the concept of ahimsa or non-violence, which is the principal concept in both Hinduism[138] and Jainism,[139] bolsters this argument.[140] While the text extols the virtue of non-violence, it also dedicates many of 700 porul couplets to various aspects of statecraft and warfare in a manner similar to Kautilya's Arthashastra[141] "An army has a duty to kill in battle, and a king must execute criminals for justice."[142] This non-mystic realism and the readiness for just war teachings are similar to those found in Hinduism.[141] According to M. S. Purnalingam Pillai, Valluvar has not condemned Saiva Siddhanta or its principles anywhere in the text,[143] and instead hints at the Vaishnavite beliefs of Valluvar.

The three parts that the Kural literature is divided into, namely, aram (virtue), porul (wealth) and inbam (love), aiming at attaining vitu (ultimate salvation), follow, respectively, the four foundations of Hinduism, namely, Dharma, Artha, Kama and Moksha.[144][145] According to Norman Cutler, the prodigious 13th-century Tamil scholar Parimelalakar – who wrote the most influential commentary on Tirukkuṟaḷ – interprets the layout and focus on the Valluvar to be synonymous with the Sanskritic concept of Puruṣārtha (the objectives of human life).[146] According to Parimelalakar, the Valluvar text covers primarily and directly the first three aspects, but not vitu (moksha, release). The text, however, does cover turavaram (renunciation) – the means to attain spiritual release. Thus, vitu is indirectly discussed.[147]

In the introductory chapters of the Kural, Valluvar cites Indra, the king of heaven, to exemplify the virtue of conquest over one's senses.[148] According to Tamil Hindu scholars such as Parimelalakar, other concepts and teachings found in Valluvar's text and also found in Hindu texts include Vedas,[149] gods (Trimurti), sattva, guṇa, munis and sadhus (renouncers), rebirth, affirmation of a primordial God, among others.[150][151][152] According to Purnalingam Pillai, who is known for his critique of Brahminism, a rational analysis of the Valluvar's work suggests that he was a Hindu, and not a Jain.[153] Similarly, J. J. Glazov, a Tamil literature scholar and the translator of the Kural text into the Russian language, sees "Thiruvalluvar as a Hindu by faith", according to a review by Kamil Zvelebil.[154]

Valluvar's mentioning of God Maha Vishnu in couplets 610 and 1103 and Goddess Lakshmi in couplets 167, 408, 519, 565, 568, 616, and 617 hints at the Vaishnavite beliefs of Valluvar.[152] Shaivites have characterised Valluvar as a devotee of Shiva and have installed his images in their temples.[155] According to Zvelebil, Valluvar sometimes uses epithets for God that are found in Hindu Dharmaśāstras and not in Jaina texts.[156] Further, in some teachings about politics, economics, and love, Valluvar undoubtedly has translated into Tamil the verses found in Sanskrit texts such as Kautilya's Arthashastra.[157]

Tamil Vedic Literature after Sangam era[edit]

Naalayira Divya Prabandham[edit]

The Naalayira Divya Prabandham (Tamil: நாலாயிரத் திவ்வியப் பிரபந்தம்) is a collection of 4,000 Tamil verses composed[158] by the 12 Alvars who lived between 5th century and 9th century CE.[159] It was compiled in its present form by Nathamuni during the 9th century. The work, an important liturgical compilation of the Tamil Alvars, marks the beginning of the canonisation of 12 Vaishnava poet saints, and these hymns are still sung extensively today. The works were lost before they were collected and organised in the form of an anthology by Nathamuni.

The devotional outpourings of the Alvars, composed during the early medieval period of Tamil history, were the catalysts behind the Bhakti Movement through their hymns of worship to Vishnu and his avatars. They praised the Divya Desams, the 108 divine realms of deities affiliated to Vaishnavism. The poetry of the Alvars echoes bhakti to God through love, and in the ecstasy of such devotions they sang hundreds of songs which embodied both depth of feeling and the felicity of expressions.[160] The collection of their hymns is known as the Naalayira Divya Prabandham. The bhakti literature that sprang from Alvars has contributed to the establishment and sustenance of a culture that deviated from the Vedic religion and rooted itself in devotion as the only path for salvation. In addition, they contributed to Tamil devotional verses independent of a knowledge of Sanskrit.[161] As a part of the legacy of the Alvars, five Vaishnavite philosophical traditions (sampradayas) developed over a period of time.[162]

The Divya Prabandham sings the praises of Narayana (Vishnu) and his many forms. The Alvars sang these songs at various sacred shrines known as the Divya Desams.[163] The Tamil Vaishnavites are also known as Ubhaya Vedanti (those that follow both Vedas, that is, the Sanskrit Rigveda, Yajurveda, Samaveda, and Atharvaveda, as well as the Tamil-language Tiruvaymoli, a work which devotees of Sri Vaishnavism regard as the Tamil Veda).[164] In many temples — Srirangam, for example — the chanting of the Divya Prabandham forms a major part of the daily service. It is also recited in some North Indian Vaishnavite temples, such as Badrinath.[165] The Divya Prabandham is recited along with the Vedas,[166] and it is given equal status to the Vedas in the Tenkalai denomination of Sri Vaishnavism, largely due to the efforts of Ramanuja who enshrined the Divya Prabandham on the same pedestal as the Vedas.[167] The text promotes Vaishnavism and Vedism together in a ratio.[164]

Tevaram[edit]

The Tevaram (Tamil: தேவாரம், denotes the first seven volumes of the twelve-volume collection Tirumurai, a Śaiva narrative of Vedic and Puranic heroes, as well as a hagiographic account of early Saiva saints set in devotional poetry.[168] The Tevaram volumes contain the works of the three most prominent Saiva Tamil poets of the 7th and 8th centuries: Sambandar, Appar, and Sundarar.[169][170][171] The three poets were not only involved in portraying their personal devotion to Shiva, but also engaged a community of believers through their songs. Their work is an important source for understanding the Śaiva Bhakti movement in the early medieval South India.[172][173] Tevaram text has been called as a Shaiva "Tamil-vētam" (a Tamil Veda) in Volume 4 of the Madras Tamil Lexicon. This equivalence with the ancient Hindu Vedas has been explained by the Tamil Shaiva scholars in that the Tevaram "resembles the Vedic hymns" by being poetry of the "highest order" that also systematically builds the philosophical foundations of Shaivism. It differs from the ancient Vedas in that it focuses on intense bhakti for Shiva.[174]

The Tevaram helped structure a devotional tradition with its own authoritative canon, and thereby negated the primacy of Vedic orthodoxy and Smartha tradition, states Champakalakshmi.[175] Yet they extend rather than reject the Vedic tradition. The hymns, states Peterson, directly praise the four Vedas and Sanskrit, adding that devotion to Shiva is same as these. For example, in Appar VI.301.1, the Tevaram states "See him who is Sanskrit of the North, and southern Tamil, and the four Vedas". Such themes appear repeatedly in this text. Thus, Tevaram is not antagonistic to the Vedic tradition, it compliments and redirects the devotee to bhakti through songs and music, for the same spiritual pursuit.[176][note 4]

In their structure and focus, the patikams (praise poem) of the Tevaram are "closely associated with early Sanskrit strotas" of the types found in Bhagavad Gita, the Bharavi, some compositions of Kalidasa and some chapters of the epic Mahabharata, all dated between about the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE, states Peterson.[177] The melodic prosody, structure and genre that the Tevaram exemplifies has roots and illustrations in the Satarudriya of the Yajurveda, an ancient prototypical devotional hymn to Rudra-Shiva.[178]

According to Sabaratnam, the Tevaram verses were more oriented towards the folk tradition. It used the Tamil language and thus set aside the primacy of Sanskrit liturgies in religious matters. Tevaram made the direct devotion to Shiva more easily accessible to the people.[179]

Ramavatharam[edit]

Ramavataram, popularly referred to as Kamba Ramayanam, is a Tamil epic that was written by the Tamil poet Kambar during the 12th century. Based on Valmiki's Ramayana (which is in Sanskrit), the story describes the life of King Rama of Ayodhya. However, Ramavatharam is different from the Sanskrit version in many aspects – both in spiritual concepts and in the specifics of the storyline.[180][181] This historic work is considered by both Tamil scholars and the general public as one of the greatest literary works in Tamil literature.[182]

The original version of Ramayana was written by Valmiki. It is an epic of 24,000 verses which depicts the journey of Rama, a prince of Ayodhya who belonged to Raghuvamsa (Solar dynasty). In Hinduism, Rama is the seventh incarnation of Vishnu(The supreme being of Vaishnavism). The entire life story of Rama, Sita and their companions allegorically discusses duties, rights and social responsibilities of an individual. It illustrates Dharma and dharmic living through model characters.[183][184]

The book is divided into six chapters, called Kandam in Tamil. The Kandams are further divided into 113 sections called Padalam (படலம்) in Tamil. These 113 sections contain approximately 10569 verses of the epic.[185]

- Bala Kandam (Chapter: Childhood)

- Ayodhya Kandam (Chapter: Ayodhya)

- Aranya Kandam (Chapter: Forest)

- Kishkindha Kandam (Chapter: Kishkindha)

- Sundara Kandam (Chapter: Beautiful)

- Yuddha Kandam (Chapter: War)[186][187]

Periya Puranam[edit]

The Periya purāṇam (Tamil: பெரிய புராணம்), that is, the great purana or epic, sometimes called Tiruttontarpuranam ("Tiru-Thondar-Puranam", the Purana of the Holy Devotees), is a Tamil poetic account depicting the lives of the sixty-three Nayanars, the canonical poets of Tamil Shaivism. It was compiled during the 12th century by Sekkizhar. It provides evidence of trade with West Asia.[189] The Periya Puranam is part of the corpus of Shaiva canonical works. All the saints mentioned in this epic poem are historical persons and not mythical. Therefore, this is a recorded history of the 63 Saiva saints called as Nayanmars (devotees of Lord Siva), who attain salvation by their unflinching devotion to Siva. The Nayanmars that he talks about belonged to different communities, different occupations and lived in different times.

Sekkilhar compiled and wrote the Periya Puranam or the Great Purana in Tamil about the life stories of the sixty-three Shaiva Nayanars, poets of the God Shiva who composed the liturgical poems of the Tirumurai, and was later himself canonised and the work became part of the sacred canon.[190] Among all the hagiographic Puranas in Tamil, Sekkilhar's Tiruttondar Puranam or Periyapuranam, composed during the rule of Kulottunga II (1133–1150 CE) stands first.[191]

Inscriptions[edit]

Velvikudi inscription[edit]

The Velvikudi inscription is an 8th-century bilingual copper-plate grant from the Pandya kingdom of southern India. Inscribed in Sanskrit and Tamil languages, it records the renewal of a grant of the Velvikudi village to a brahmana by the Pandya king Nedunjadaiyan Varaguna-varman I alias Jatila Parantaka (r. c. 768—815 CE) in c. 769-770 CE.

The inscription begins with a Sanskrit portion that invokes the God Shiva, and describes the mythical lineage of the Pandya kings, naming the sage Agastya as their family priest. It also gives the following account of the dynasty's origin:[192] At the end of the previous kalpa (age), a king named Pandya ruled the coastal region. This king was reborn as Budha, the son of the Moon.[193] Budha's son Pururavas introduced the dynasty's emblem - a pair of fish, and shared his throne and taxes with Indra.[194] Pururavas' descendant Maravarman was a patron of the learned, who conquered several enemies and gave away heaps of gold.[192] These inscriptions shows the Vedic belief of the king, as the inscription mentions the Rigvedic deities such as Pururavas, Budha Agastya and Indra[195] The inscription further mentions that the enemy of king Pallavamalla ran away from the battlefield when faced with Rajasimha, wondering if the Pandya king was Shiva, Vishnu, or Indra.[192] Rajasimha generously distributed his wealth among the brahmanas, beggars and temples. He married the daughter of the Malava king, and their son was the next ruler, Jatila.[192] (Sastri identified Malava with modern Mala-nadu.[196]) Jatila alias Parantaka was almost equal to Skanda, the son of Shiva.[192]

The Tamil version explains a Vedic Sacrifice done by a Brahmin called Narkorran (Tamil Lexicon: Naṟkoṟṟan who knew the Vedas and a headman of Korkai. The Sacrifice took place at Velvikudi (Vēḷvikkuṭi), with support of the Pandya king Palyaga Mudukudimi Peurvaluti (Palyāka Mutukuṭumi Peruvaḻuti).[193] The inscription defines the boundaries of the Velvikudi village with reference to landmarks such as vegetation, ponds, mounds, and other villages such as Payal and Kulandai;[197] It mentions that the king Arikesari Asamasaman Maravarman defeated the king of Kerala several times at the strongly-fortified town of Puliyur and performed the hiranyagarbhavrtham (Which is mentioned in the Atharvaveda) and tulabhara gift-giving ceremonies, he protected the brahmanas and the infirm.[198] It also mentions Maravarman Rajasimha I reached Pandi-Kodumudi, and worshipped Pashupati (Shiva). He established a marital alliance with the Gangaraja.[199] He performed the gift-giving ceremonies gosahasra (gift of cows), hiranyagarbha, and tulabhara. He relieved the distress of those who studied the Vedas, and repaired the fortifications at Kudal, Vanji and Kozhi.[198] The inscription ends with the Sanskrit portion with names Mangalaraja Madhuratara of Karavandapura as the executor (ajnapti) of the grant.[197] It describes him as a vaidyaka, a master of the shastras, a poet and an orator. This portion ends with four Vaishnavite imprecatory verses (cursing those who violate the grant deed).[199] This is an important scripture which mentions Vedic Sacrifices.

Other important Inscriptions[edit]

There are several other inscriptions of Vedic sacrifices in Ancient Tamilakam, one of the earliest inscriptions are from the early 6th century by the Pallava king Simhavarman III According to the Sivan Vāyil inscription, he performed 10 Aśvamedha yajña (Daśāśvamedha), Bahusuvarṇa & Kratu sacrifices.[200] Robert Lingat states that epigraphical evidence such as the Pallava inscriptions confirm that Apastamba tradition existed in South India, in ancient times.[201]

Most of the Tamil country inscriptions were written in Tamil, but beginning in the 6th century, both stone and copper-plate inscriptions were written in Sanskrit as well, some being bilingual.[202] Indian archaeologists have discovered hundreds of inscriptions during the last 120 years. Professor E. Hultzsch began collecting South Indian inscriptions systematically from the latter part of 1886 when he was appointed Epigraphist to the Government of Madras.

—Sanctum entrance, Adivaraha cave (7th century);

earliest avatar-related epigraphy[205][206][note 5]

Inscriptions in A potsherd excavated from the Kodumanal Archeological site has the name Kannan Adhan inscribed in Tamil Brahmi. The period of this inscription is estimated to be 2-3 century BCE. Kannan is one of the Tamil names describing Lord Krishna and this is one of the earliest reference of His name found in Tamilakam. Thirukural is another example from the Sangam literature mentioning Krishna as Kannan in his couplet 1103.[208]

Many other Inscriptions of Pallavas on Vedas and puranas were made between 500 CE to 700 CE. Later many other chola and Pandyas had also made inscriptions. There are several inscriptions of Medival cholas donating and Building temples for teaching the Vedas. The Parthasarathy temple, Parthivapuram is one of the Vedic schools located in Kanyakumari built by the king Karunandadakkan of the Ay dynasty around 800 CE.[209] A 923 CE inscription found in front of the temple records gifts to the temple, by Panchavan Brahmadhiraja alias Kumaran Narayanan.[209] Another 10th century inscription (dated before 940 CE) discovered at the temple, in Tamil language and Vatteluttu is dated to the reign of Para-kesari-varman Virasholap-perumangadigal, who is identified with Parantaka I alias Virachola.[209]

The fourth and fifth plates of the copper plates provide the Vedic and related studies focus and constitution for the school:[210][211][212]

- it will host 45 students for higher studies in Paviliya-Bahv-rc (Bhavisya) sakha studies[note 6]

- it will host 36 students for higher studies in Taittiriya sakha studies[note 7]

- it will host 14 students for higher studies in Talavakara sakha studies[note 8]

- the hostel and school expenses will be paid in part from the taxes collected from the following villages: Omayanadu, Singulunadu, Mudalanadu, Padaippanadu and Valluvanad

- it states that no visitor, no staff and no student will interfere in the daily operations of the temple and school

- it lists the rules of conduct for temple and school servants and teachers

- it lists the rules for selection and admission for students, and their behavior while at school; for example, it states that five senior students or teachers must test the candidate's ability to recite fluent Sanskrit and examples of Vedic passages;[216] the students should not possess or carry weapons inside the school; the students should not keep female companions or concubines inside the school; minor infractions by the student would lead to fines and loss of meals in the school[210]

Varadharajaperumal temple, Thirubuvanai, built by Chola king Parantaka I (907-955 CE) was another school where Vedas were thought. An inscription dated to the 30th regnal year of Rajadhiraja I (c. 1048 CE), mentions teaching Rig Veda, Yajur Veda, Chandogasama, Talavakrasama, Apurva, Vajnasaneya, Bodhayaniya Sathashatandha Sutra and explanations of sastras and epics like Ramayana are also found in the temple.[20] There is also mention of the remuneration to the teachers and students in the form of paddy.[217] There are inscriptions in the temple from the period of Rajadhiraja Chola indicating recital of Tiruvaymoli, the famous works of the Alvar saint Nammalvar.[218]

Several kings built temples for gods like and had intense faith in the Ramayana which is a part of the Vedic religion. Even the oldest Tamil texts Purananuru[219][54] and Akanaṉūṟu[220] mention scenes of Ramayana in a way that Rama is filled in their hearts. The Chola king Parantaka I named himself "Sangrama Raghava" after his conquest of Sri Lanka, while his son Aditya I was called Kothandarama. Some later Pandya kings also made contributions to the temple's of Rama.[221] A mutilated inscription in the Adi Jagannatha Perumal Temple (which was a temple as well as a Vedic school) was inscribed during the 37th year of Maravarman Sundara Pandyan in 1305 records order of a minister by name Arya Chakravarthi. Historians believe some portions of the Adi Jagannatha Perumal Temple tower might also have been built by Jaffna kings, who were friends of Pandya Empire and also rulers of Rameswaram.[222]

Another Famous temple cum Vedic school dedicated to Rama is Eri-Katha Ramar Temple was built during the Pallava era, and is estimated to be 1600 years old. The Moolavar (presiding deity) of the temple is Lord Rama, thus making this one of the oldest temples of lord Rama in South India. The temple has inscriptions indicating generous gifts from Chola king Parantaka I.[221] The place was once famous during the rule of Cholas who ruled this place as Maduranthaga Chaturvedi Mangalam after the Chola ruler Madurantaga Uttama Chola (973 -85 CE). It is believed that Gandaraditya donated the village to the Vedics (Chaturvedi - one who knows all four vedas) of the place and hence it came to be known as Chaturvedi Mangalam.

Uthiramerur was another Vedic school which originally existed as a Brahmin Village. The Pallava king Nandivarman II (720–796 CE) formally established it as a brahamdeya village around 750 CE.[223] It is believed that he donated the village to Vedic Brahmins from Srivaishanva community.

Notes[edit]

- ↑ It is certain that the hymns of the Rig Veda post-date Indo-Iranian separation of ca. 2000 BCE and probably that of the relevant Mitanni documents of c. 1400 BCE. The oldest available text is estimated to be from 1200 BCE. Philological estimates tend to date the bulk of the text to the second half of the second millennium:

- Max Müller: "the hymns of the Rig-Veda are said to date from 1500 B.C."[8]

- The EIEC (s.v. Indo-Iranian languages, p. 306) gives 1500–1000 BCE.

- Flood and Witzel both mention c. 1500–1200 BCE.[7][9]

- Anthony mentions c. 1500–1300 BCE.[10]

- Thomas Oberlies (Die Religion des Rgveda, 1998, p. 158) based on 'cumulative evidence' sets a wide range of 1700–1100 BCE.[11] Oberlies 1998, p. 155 gives an estimate of 1100 BCE for the youngest hymns in book 10.[12]

- Witzel 1995, p. 4 mentions c. 1500–1200 BCE. According to Witzel 1997, p. 263, the whole Rig Vedic period may have lasted from c. 1900 BCE to c. 1200 BCE: "the bulk of the RV represents only 5 or 6 generations of kings (and of the contemporary poets)24 of the Pūru and Bharata tribes. It contains little else before and after this “snapshot” view of contemporary Rgvedic history, as reported by these contemporary “tape recordings.” On the other hand, the whole Rgvedic period may have lasted even up to 700 years, from the infiltration of the Indo-Aryans into the subcontinent, c. 1900 B.C. (at the utmost, the time of collapse of the Indus civilization), up to c. 1200 B.C., the time of the introduction of iron which is first mentioned in the clearly post-vedic hymns of the Atharvaveda."

- ↑ कुमारं माता युवतिः समुब्धं गुहा बिभर्ति न ददाति पित्रे । अनीकमस्य न मिनज्जनासः पुरः पश्यन्ति निहितमरतौ ॥१॥ कमेतं त्वं युवते कुमारं पेषी बिभर्षि महिषी जजान । पूर्वीर्हि गर्भः शरदो ववर्धापश्यं जातं यदसूत माता ॥२॥ हिरण्यदन्तं शुचिवर्णमारात्क्षेत्रादपश्यमायुधा मिमानम् । ददानो अस्मा अमृतं विपृक्वत्किं मामनिन्द्राः कृणवन्ननुक्थाः ॥३॥ क्षेत्रादपश्यं सनुतश्चरन्तं सुमद्यूथं न पुरु शोभमानम् । न ता अगृभ्रन्नजनिष्ट हि षः पलिक्नीरिद्युवतयो भवन्ति ॥४॥ (...) Hymn 5.2, Wikisource;

English: "The youthful Mother keeps the Boy in secret pressed to her close, nor yields him to the Father. But, when he lies upon the arm, the people see his unfading countenance before them. [5.2.1] What child is this thou carriest as handmaid, O Youthful One? The Consort-Queen hath bome him. The Babe unborn increased through many autumns. I saw him born what time his Mother bare him. [5.2.2] I saw him from afar gold-toothed, bright-coloured, hurling his weapons from his habitation, What time I gave him Amrta free from mixture. How can the Indraless, the hymnless harm me? [5.2.3] I saw him moving from the place he dwells in, even as with a herd, brilliantly shining. These seized him not: he had been born already. They who were grey with age again grow youthful. [5.2.4]

– Translated by Ralph T.H. Griffith, Wikisource - ↑ Verse 7.26.2 states Kumara is Skanda, but there are stylistic differences between this verse and the rest of the chapter. This may be because this verse was interpolated into the text at a later date.[50]

- ↑ For a few additional examples (Translator: V.M.Subramanya Ayyar), see:

Tevaram I.24.10: "the god in kāḻi who pressed down angrily by gently fixing his toe to crush the arakkaṉ who lifted (the mountain), the pure one who smears the ash which is dust, took pity (on him) as he began to praise god by singing Sama Veda (cāma vētam);"

Tevaram I.52.1: "one who dwells in Neṭuṅkaḷam, you who have the Vedas (Vetams) as your word! whose dress is a skin! who has on his long caṭai a prospering crescent! unless people praise you in the above mentioned manner; you do not mind the faults of people who have defects; weed out the affliction of those who have moral firmness and who are superior by their principles.;"

Tevaram V.30.6: "(My mind!) worship with folded hands sincerely early in life, Shiva (Civaṉ) who chants the four Vedas (Vētams) which contain good things, who receives alms in the teethless white skull, who is in tillai (citamparam), and the god who is in parāittuṟai in the south;

Tevaram VII.69.9: "God well-versed in Vedic love who destroyed the precious life of the Kālaṉ (God of death) who came without any regard, to bind by the noose Markaṇṭeyaṉ the bachelor who fell prostrate at the feet of Shiva (Civaṉ) with flowers from which fragrance was spreading, with the leg! the god in Tirumullaivāyil of great wealth! the spiritual preceptor who gave out the meanings of the Vedas (Vētams) which are eternal; root out the sufferings that I your slave have to undergo. - ↑ This 7th century (or early 8th century) inscription is significant for several reasons. It is the earliest known stone inscription about the ten avatars of Vishnu, and prior to that, they are found in older texts. The stone inscription mentions the Buddha as an avatar of Vishnu in a Hindu temple. It also does not mention Krishna, but Balarama consistent with old Hindu and Jain texts of South India, the former equating Krishna to be identical to Vishnu.[205][207]

- ↑ This is one of the Rigveda sakha.[213]

- ↑ This is one of the Yajurveda sakha.[214]

- ↑ This is one of the Samaveda sakha, the Jaiminiyas.[215]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 JV Chelliah 1946, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-15

- ↑ https://www.tamilvu.org/ta/tdb-titles-cont-lite-html-pandiyan-palkalasalai-280879

- ↑ Patiṟṟuppattu, poem 64

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 R Parthasarathy (Translator) 2004, pp. 25-27.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.in/books?id=HWPg7EvPirgC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Flood 1996, p. 37.

- ↑ Müller 1892.

- ↑ Witzel 1995, p. 4.

- ↑ Anthony 2007, p. 454.

- ↑ Oberlies 1998, p. 158.

- ↑ Oberlies 1998, p. 155.

- ↑ see e.g. Radhakrishnan & Moore 1957, p. 3; Witzel 2003, p. 68; MacDonell 2004, pp. 29–39.

- ↑ Sanskrit literature (2003) in Philip's Encyclopedia. Accessed 2007-08-09

- ↑ Sanujit Ghose (2011). "Religious Developments in Ancient India" in World History Encyclopedia.

- ↑ https://www.thehindu.com/features/friday-review/history-and-culture/Vedic-route-to-the-past/article14397101.ece

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Kamil Zvelebil (1974). Tamil Literature. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 49. ISBN 978-3-447-01582-0.

- ↑ https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/ettuthokai-purananuru-201-400/

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 JV Chelliah 1946, p. 41.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Ayyar, P. V. Jagadisa (1982). South Indian Shrines: Illustrated. Asian Educational Services. p. 182. ISBN 9788120601512.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 131.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 131–133.

- ↑ David Shulman 2016, p. 28.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 131–132 with footnote 1.

- ↑ Bartholomaeus Ziegenbalg (2010). Tamil Language for Europeans: Ziegenbalg's Grammatica Damulica. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-3-447-06236-7.

- ↑ Willem van Reijen; Willem G. Weststeijn (1999). Subjectivity. Rodopi. pp. 321–322. ISBN 90-420-0728-1.

- ↑ Sir Ralph Lilley Turner - A comparative dictionary to the Indo-Aryan languages, Entry 3110 kāˊvya https://dsalsrv04.uchicago.edu/cgi-bin/app/soas_query.py?qs=kāvikā&searchhws=yes

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 142–146 with footnotes.

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe 1977, pp. 180–182.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 https://books.google.co.in/books?id=n2DxBwAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Hartmut Scharfe 1977, pp. 180–181.

- ↑ Journal of Tamil Studies, Volume 1. International Institute of Tamil Studies. p. 131. Archived from the original on 13 November 2017.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/20/mode/2up

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/99/mode/2up

- ↑ S. M. Srinivasa Chari (1994). Vaiṣṇavism: Its Philosophy, Theology, and Religious Discipline. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 147. ISBN 978-81-208-1098-3.

- ↑ Brahma: Hindu god Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 29, 56–57.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 JV Chelliah 1946, pp. 98–100.

- ↑ JV Chelliah 1946, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Monica Smith (2006). "The Archaeology of Food Preference". American Anthropologist. 108 (3): 480–493.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/97/mode/2up

- ↑ Theosophical Siftings. Theosophical Pub. Society.

- ↑ Sheshadri, Dr T. V. Satyanarayana, Dr A. S. Venugopala Rao, Smt T. N. Saraswati, Prof N. Nanjunda Sastry, Dr K. L. Shankaranarayana Jois, Sri Hari, M. N. Lakshminarasimha Bhatta and S. L. Maharshis of Ancient India. Bharatha Samskruthi Prakashana. ISBN 978-93-89028-73-7.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Clothey 1978, pp. 49-53.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Clothey 1978, pp. 49-51.

- ↑ Clothey 1978, pp. 46-51.

- ↑ Clothey 1978, pp. 48-50.

- ↑ Clothey 1978, pp. 50-51.

- ↑ The Thirteen Principal Upanishads Archived 25 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine, Robert Hume, Oxford University Press, page 262 with footnote 3

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 54-55.

- ↑ George Hart & Hank Heifetz 2001, pp. xxi, 3–4, 28–32, 41, 139–140, 206, 220.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Hart, George L; Heifetz, Hank. The four hundred songs of war and wisdom : an anthology of poems from classical Tamil : the Puṟanāṉūṟu. Columbia University Press. pp. 219-220. ISBN 9780231115629.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Kalakam, Turaicămip Pillai (ed.). Purananuru. Madras.

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-15

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-9

- ↑ https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/ettuthokai-purananuru-1-200/

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-15

- ↑ https://www.tamilvu.org/ta/tdb-titles-cont-lite-html-pandiyan-palkalasalai-280879

- ↑ https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/ettuthokai-purananuru-201-400/

- ↑ https://www.thehindu.com/society/faith/importance-of-avani-avittam/article67243831.ece

- ↑ Purananuru poem 166

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-166

- ↑ https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/ettuthokai-purananuru-1-200/

- ↑ Prasoon, Ch.2, Vedang, Kalp.

- ↑ "Is Sacrificial Killing Justified? from the Chapter "The Vedas", in Hindu Dharma". kamakoti.org. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ↑ https://www.poetrynook.com/poem/purananuru-part-367

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 29, 57.

- ↑ Dinamalar Temples, Kaliyuga Varadaraja Perumal Temple

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n81/mode/2up

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 57–58.

- ↑ JV Chelliah 1946, pp. 17–20.

- ↑ JV Chelliah 1946, p. 33.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/38/mode/2up

- ↑ JV Chelliah 1946, p. 221.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1974, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 58–59.

- ↑ 78.0 78.1 78.2 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n257/mode/2up

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n255/mode/2up

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n303/mode/2up

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 Tieken, Herman. Kāvya in South India: Old Tamil Caṅkam Poetry. BRILL. p. 186. ISBN 978-90-04-48609-6.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n309/mode/2up

- ↑ https://books.google.co.in/books?id=HWPg7EvPirgC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 R Parthasarathy (Translator) 2004, pp. 25-26.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 85.2 V R Ramachandra Dikshitar 1939, pp. 193, 237

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1974, p. 130.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1974, pp. 130-132.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 Silappadikaram.

- ↑ Tamil Geographies: Cultural Constructions of Space and Place in South India. SUNY Press. 22 May 2008. ISBN 9780791472453.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 "The Silappadikaram". 26 August 2023.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 D. Kinsley (1974), Through the Looking Glass, History of Religions, 13(4), pp. 270–305

- ↑ "58th name in the Vishnu Sahasranama is लोहिताक्षः - lohitākṣaḥ - Red-eyed"

- ↑ Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya, ed. (2009). A Social History of Early India. Jointly published by CSC and Pearson Education for the Project of History of Indian Science, Philosophy and Culture. p. 238.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1974, pp. 140–143.

- ↑ 95.0 95.1 Alain Danielou (Translator) 1993, pp. 18-23.

- ↑ Alain Danielou (Translator) 1993, pp. 1-4.

- ↑ Alain Danielou (Translator) 1993, pp. 7-13.

- ↑ "Kanya Kumari Temple". Kanyakumari info. 2012. Retrieved 24 July 2013.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 99.3 https://books.google.co.in/books?id=wl7T45yhh1sC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Bryant 2006, pp. 195–196: "At the same time, preliminary signs of tension or unease with such slaughter are occasionally encountered even in the earlier Vedic period. As early as the Ṛgveda, sensitivity is shown toward the slaughtered beasts; for example, one hymn notes that mantras are chanted so that the animal will not feel pain and will go to heaven when sacrificed. The Sāmaveda says: "we use no sacrificial stake, we slay no victims, we worship entirely by the repetition of sacred verses." In the Taittiriīya Āraṇyaka, although prescriptions for offering a cow at a funeral procession are outlined in one place, this is contradicted a little further in the same text where it is specifically advised to release the cow in this same context, rather than kill her. Such passages hint, perhaps, at proto-tensions with the gory brutality of sacrificial butchery, and fore-run the transition between animals as objects and animals as subjects."

- ↑ Rosen 2020, pp. 409–410: "Nonetheless, it is likely that even if flesh eating was widespread, and indulged in by certain sages, it occurred solely within the sacrificial context, or, beyond that, only by hunters and warriors in the forest, who also used it in sacrifice. In fact, this is what is indicated by the vast majority of Vedic texts on the subject, and it is certainly the version that has been passed down in later Hindu traditions. For further proof that meat eating occurred in Vedic culture only within the confines of sacrifice, see Schmidt 2010."

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.in/books?id=OQ33i496MsIC&pg=PA48&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ Your feet are greater than you! You have very great godly attributes! The precious Vēdās, chanted by the Brahmins resembling you, reveal your attributes!

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Lubotsky, Alexander. "The Iconography of the Viṣṇu Temple at Deogarh and the Viṣṇudharmottarapurāṇa". Ars Orientalis. 26: 65–80. ISSN 0571-1371. JSTOR 4629500.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 106.2 https://sangamtranslationsbyvaidehi.com/ettuthokai-paripadal/

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Daniélou, Alain. The Myths and Gods of India: The Classic Work on Hindu Polytheism from the Princeton Bollingen Series. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. pp. 168. ISBN 978-0-89281-354-4.

- ↑ Macdonell, Arthur Anthony. ... Vedic mythology. Princeton Theological Seminary Library. Strassburg : Karl J. Trübner. pp. 41.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Arthur Anthony Macdonell. Vedic Index Of Names And Subjects Vol.ii. pp. 245.

- ↑ Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa: Text in Devanāgari and Translation. Sri Aurobindo Kapāli Sāstry Institute of Vedic Culture. p. 107 (Volume 1). ISBN 978-81-7994-166-9.

- ↑ 111.0 111.1 Soifer 1991, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Trudy Ring; Robert M. Salkin; Sharon La Boda (1995). Asia and Oceania: International Dictionary of Historic Places. Taylor & Francis. pp. 912–. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ↑ "Mahabalipuram – The Workshop of Pallavas – Part II". Adi-Varaha Perumal Cave Temple. Puratatva.in. Archived from the original on 21 April 2012. Retrieved 23 February 2013.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1973, p. 61.

- ↑ Kamil Zvelebil 1974, p. 25.

- ↑ "RigVeda Book I XXI 'Aśvins and Others' (Sanskrit and Transliteration)". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 19 January 2020.

- ↑ JV Chelliah 1946, pp. 84, 91, 94.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n119/mode/2up

- ↑ Rosen, Elizabeth. "REVIEW: Prince ILango Adigal, Shilappadikaram (The anklet Bracelet), translated by Alain Damelou". Artibus Asiae. 37 (1/2): 149. JSTOR 3250226.

- ↑ "Hymns of the Samaveda". www.sacred-texts.com. Retrieved 22 January 2020.

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/pattupattutentamilidyllschelliahj.v._108_Q/page/n123/mode/2up

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 Zvelebil 1973, pp. 125–126.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 119–126.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, p. 130.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Zvelebil 1973, pp. 125–127 with footnotes.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Emmanuel Francis (2017). "The Other Way Round: From Print to Manuscript" (PDF). In Vincenzo Vergiani; Daniele Cuneo; Camillo Alessio Formigatti (eds.). Indic Manuscript Cultures through the Ages: Material, Textual, and Historical Investigations. De Gruyter. pp. 321–322. doi:10.1515/9783110543100. ISBN 978-3-11-054312-4.

- ↑ Abraham Mariaselvam (1988). The Song of Songs and Ancient Tamil Love Poems: Poetry and Symbolism. Gregorian. p. 245. ISBN 978-88-7653-118-7.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 129–131 with footnotes.

- ↑ R., Dr. Vijayalakshmy (2001). An introduction to religion and Philosophy - Tévarám and Tivviyappirapantam (1st ed.). Chennai: International Institute of Tamil Studies. pp. 471–2.

- ↑ Pillai, 1994.

- ↑ Sundaram 1990, pp. 7–16.

- ↑ Blackburn 2000, pp. 449–482.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Lal 1992, pp. 4333–4334, 4341.

- ↑ Holmström, Krishnaswamy, and Srilata, 2009, p. 5.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1975, p. 124.

- ↑ Iraianban 1997, p. 13.

- ↑ Tähtinen, Unto (1976). Ahimsa. Non-Violence in Indian Tradition. London. pp. 2–3 (English translation: Schmidt p. 631). ISBN 0-09-123340-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Laidlaw 1995, pp. 26–30.

- ↑ Sundaram 1987, pp. xiii–xvii, Appendix note on verse 1103.

- ↑ 141.0 141.1 Roy, Kaushik. Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–154, context: 144–154 (Chapter: Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia). ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8.

- ↑ Ananthanathan, A.K. (1994). "Theory, and Functions of the State The Concept of aṟam (virtue) in Tirukkural". East and West. 44 (2/4): 325. JSTOR 29757156., Quote: "Non-killing is an absolute virtue (Aram) in the Arattuppal (the glory of virtue section), but the army's duty is to kill in battle and the king has to execute a number of criminals in the process of justice. In these cases, the violations of the Aram [in the earlier section] are justified [by Thiruvalluvar] in virtue of the special duties cast on the king and the justification is that 'a few wicked must be weeded out to save the general public' (TK 550)."

- ↑ Pillai, 2015, p. 75.

- ↑ Roy, Kaushik. Hinduism and the Ethics of Warfare in South Asia: From Antiquity to the Present. Cambridge University Press. pp. 152–155. ISBN 978-1-107-01736-8.

- ↑ Sundaram 1987, pp. xiii-xvii, Appendix note on verse 1103.

- ↑ Cutler 1992, pp. 553–554.

- ↑ Cutler 1992, pp. 554–555.

- ↑ Sundaram 1987, pp. 21,159.

- ↑ Ananthanathan, A.K. (1994). "Theory and Functions of the State The Concept of aṟam (virtue) in Tirukkural". East and West. 44 (2/4): 321. JSTOR 29757156.

- ↑ Natarajan 2008, pp. 1–6.

- ↑ Cutler 1992, pp. 555–558.

- ↑ 152.0 152.1 Kovaimani & Nagarajan 2013, pp. 145–148.

- ↑ Blackburn 2000, pp. 464–465.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamil (1984). "Tirukural, translated from Tamil into Russian by J. Glazov". Archiv Orientální. 32: 681–682.

- ↑ Pruthi & Sharma 1995, p. 113.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, p. 157.

- ↑ Zvelebil 1973, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ https://books.google.co.in/books?id=8TwHhuZrZ-wC&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_ge_summary_r&cad=0#v=onepage&q&f=false

- ↑ "Indian Literature Through the Ages". Indian literature, Govt of India. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ "About Alvars". divyadesamonline.com. Archived from the original on 21 June 2007. Retrieved 2 July 2007.

- ↑ Mittal, S. G. R.; Thursby (2006). Religions of South Asia: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 27. ISBN 9780203970027.

- ↑ Rajarajan, R.K.K. (2013). "Historical sequence of the Vaiṣṇava Divyadeśas. Sacred venues of Viṣṇism". Acta Orientalia, Societates Orientales Danica Fennica Norvegia Svecia. 74: 37–90.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 Carman, John. The Tamil Veda: Pillan's Interpretation of the Tiruvaymoli. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 4.

- ↑ Prabhu, S. "Dance of Devotion". The Hindu. ISSN 0971-751X. Retrieved 6 March 2021.

- ↑ Ramesh, M. S. 108 Vaishnavite Divya Desams: Divya desams in Chola Nadu. T.T. Devasthanams. p. 42.

- ↑ Gupta, Sonika; Padmanabhan, Sudarsan. Politics and Cosmopolitanism in a Global Age. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-34132-1.

- ↑ Cort 1998, p. 177.

- ↑ Ignatius Hirudayam, "Canonical Books of Saivism and Vaishnavism in Tamil and Sanskrit" in Menachery 2010, p. 16 ff.

- ↑ Cutler 1987, p. 4

- ↑ Zvelebil 1974, p. 92

- ↑ Sabaratnam 2001, p. 25

- ↑ Schüler 2009, p. 32

- ↑ Kandiah 1973, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ R. Champakalakshmi 2007, p. 53

- ↑ Peterson 1989, pp. 69–74.

- ↑ Peterson 1989, pp. 24–26.

- ↑ Peterson 1989, pp. 26–27.

- ↑ Sabaratnam 2001, p. 26

- ↑ P S Sundaram. Kamba Ramayana. Penguin Books Limited. pp. 18–. ISBN 978-93-5118-100-2.

- ↑ Aiyar, V V S. Kamba Ramayanam - A Study with translations in verse or poetic prose of over four thousand of the original poems. Parliament Street, New Delhi: Delhi Tamil Sangam. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ "Focus on Kamban, poet extraordinaire". The Hindu. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ William H. Brackney (2013). Human Rights and the World's Major Religions, 2nd Edition. ABC-CLIO. pp. 238–239. ISBN 978-1-4408-2812-6.

- ↑ Roderick Hindery (1978). Comparative Ethics in Hindu and Buddhist Traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 95–124. ISBN 978-81-208-0866-9.

- ↑ Sujit Mukherjee (1998). A Dictionary of Indian Literature: Beginnings-1850. Orient Blackswan. p. 162. ISBN 978-81-250-1453-9.

- ↑ Mudaliyar, V S. Kamba Ramayanam - A condensed version in English verse and prose. New Delhi: Ministry of Education and Youth Services, Government of India. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ Hart, George L; Heifetz, Hank. The Forest Book of the Ramayana of Kampan. Berkerley, United States: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520060883.

- ↑ T N Ramachandran. "The Puranam of Somasi Maara Nayanar". Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- ↑ Glimpses of life in 12th century South India

- ↑ A Dictionary of Indian Literature By Sujit Mukherjee.

- ↑ Medieval Indian Literature By K. Ayyappapanicker, Sahitya Akademi.

- ↑ 192.0 192.1 192.2 192.3 192.4 H. K. Sastri 1983, p. 305.

- ↑ 193.0 193.1 H. K. Sastri 1983, p. 293.

- ↑ Herman Tieken 2001, pp. 135-136.

- ↑ Dandekar, R.N. (1962). Indian Mythology in S. Radhakrishnan ed. The Cultural Heritage of India, Calcutta: The Ramakrishna Mission Institute of Culture, ISBN 81-85843-03-1, pp.229–30, 230ff

- ↑ H. K. Sastri 1983, p. 297.

- ↑ 197.0 197.1 S.C. Mishra & Manisha Agnihotri 2009, p. 215.

- ↑ 198.0 198.1 H. K. Sastri 1983, p. 307.

- ↑ 199.0 199.1 H. K. Sastri 1983, p. 294.

- ↑ "SIVANVĀYIL INSCRIPTION OF SIṂHAVARMĀ – EARLIEST EPIGRAPH IN GRANTHA SCRIPT".

- ↑ Robert Lingat 1973, p. 22.

- ↑ "History and Culture of Tamil Nadu : As Gleaned from the Sanskrit Inscriptions". Retrieved 14 March 2007.

- ↑ Rao Bahadur H. Krishna Sastri (1926), Two Statues of Pallava Kings and Five Pallava Inscriptions in a Rock temple at Mahabalipuram, Memoirs of the Archaeological Survey of India, Volume 26, pages 5-6

- ↑ D. Kiran Kranth Choudary; C. Udayalakshmi (2006). Rāmāyaṇa in Indian Art and Epigraphy. Harman. p. 19. ISBN 978-81-86622-76-6.

- ↑ 205.0 205.1 K R Srinivasan (1964), Cave temples of the Pallavas, Archaeology Survey of India, Government of India, pages 166-175

- ↑ Michael Dan Rabe; G. John Samuel (2001). The Great penance at Māmallapuram: deciphering a visual text. Institute of Asian Studies. p. 124. ISBN 978-81-87892-00-7.

- ↑ Nagaswamy, R (2008). Mahabalipuram (Mamallapuram). Oxford University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-19-569373-7.

- ↑ https://www.ytamizh.com/thirukural/kural-1103/

- ↑ 209.0 209.1 209.2 K.G. Krishnan, Mysore (1989). "Parthivapuram Inscription of (Kollam) Year 98+1". In K.V. Ramesh (ed.). Epigraphia Indica (PDF). Vol. XLI. Archaeological Survey of India. pp. 1–6.

- ↑ 210.0 210.1 T.A. Gopinatha Rao (1910), Travacore Archaeological Series, Volume 1, pp. 1-14

- ↑ SR Rajakrishnan and Ajit Kumar (2016), Heritage, Volume 4, University of Kerala, pp. 454-458

- ↑ Justin Wilson (1998), Education in Medieval Tamilnadu: An Epigraphical Peep into its nature, Proceedings of the Indian History Congress, Volume 59, pp. 1057-1064, JSTOR 44147081

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2018). Education in Ancient India. BRILL Academic. p. 175 footnote 62. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6.

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2018). Education in Ancient India. BRILL Academic. p. 175 footnote 63. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6.

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2018). Education in Ancient India. BRILL Academic. p. 175 footnote 64. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6.

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (2018). Education in Ancient India. BRILL Academic. p. 175. ISBN 978-90-474-0147-6.

- ↑ Madhavan, Chithra (2014). Vishnu temples of South India, Volume 4, Tamil Nadu (1st ed.). Alpha Land Published Pvt. Limited. pp. 71–76. ISBN 978-81-908445-3-6.

- ↑ Pal, Susant (2014). Imbibed In Faith. Partridge Publishing. p. 284. ISBN 9781482812596.

- ↑ Hart, George L; Heifetz, Hank. The four hundred songs of war and wisdom : an anthology of poems from classical Tamil : the Puṟanāṉūṟu. Columbia University Press.

- ↑ Dakshinamurthy, A. "Akananuru: Neytal – Poem 70". Akananuru. Retrieved 22 July 2019.

- ↑ 221.0 221.1 K.V., Raman; T., Padmaja. Indian Epic Values: Rāmāyaṇa and Its Impact : Proceedings of the 8th International Rāmāyaạ Conference. Peeters Publishers. p. 85. ISBN 9789068317015.

- ↑ C., Rasanayagam (1993). Ancient Jaffna. Asian Educational Services. p. 346. ISBN 9788120602106.

- ↑ "Constitution 1,000 years ago". The Hindu. Chennai, India. 11 July 2008.