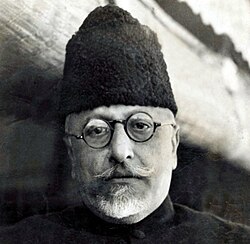

Abul Kalam Azad

Maulana Sayyid Abul Kalam Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al-Hussaini Azad ((![]() listen (help·info)) 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following India's independence, he became the First Minister of Education in the Indian government. He is commonly remembered as Maulana Azad; the word Maulana is an honorific meaning 'Our Master' and he had adopted Azad (Free) as his pen name. His contribution to establishing the education foundation in India is recognised by celebrating his birthday as National Education Day across India.[2][3]

listen (help·info)) 11 November 1888 – 22 February 1958) was an Indian independence activist, Islamic theologian, writer and a senior leader of the Indian National Congress. Following India's independence, he became the First Minister of Education in the Indian government. He is commonly remembered as Maulana Azad; the word Maulana is an honorific meaning 'Our Master' and he had adopted Azad (Free) as his pen name. His contribution to establishing the education foundation in India is recognised by celebrating his birthday as National Education Day across India.[2][3]

Abul Kalam Azad | |

|---|---|

| |

| 1st Minister of Education | |

| In office 15 August 1947 – 2 February 1958 | |

| Prime Minister | Jawaharlal Nehru |

| Preceded by | Office Established |

| Succeeded by | K.L. Shrimali |

| Member of the Constituent Assembly of India | |

| In office November 1946 – 26 January 1950 | |

| President of the Indian National Congress | |

| In office 1923–1924 | |

| Preceded by | Mohammad Ali Jauhar |

| Succeeded by | Mahatma Gandhi |

| In office 1940–1946 | |

| Preceded by | Rajendra Prasad |

| Succeeded by | J. B. Kripalani |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 11 November 1888[1] Mecca, Hejaz, Ottoman Empire (present-day Saudi Arabia) |

| Died | 22 February 1958 (aged 69) Delhi, India |

| Cause of death | Stroke |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Spouse(s) | Zulaikha Begum |

| Occupation | Theologian, scholar, political activist |

| Awards | Bharat Ratna (posthumously in 1992) |

| Signature |  |

As a young man, Azad composed poetry in Urdu, as well as treatises on religion and philosophy. He rose to prominence through his work as a journalist, publishing works critical of the British Raj and espousing the causes of Indian nationalism. Azad became the leader of the Khilafat Movement, during which he came into close contact with the Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi. Azad became an enthusiastic supporter of Gandhi's ideas of non-violent civil disobedience, and worked to organise the non-co-operation movement in protest of the 1919 Rowlatt Acts. Azad committed himself to Gandhi's ideals, including promoting Swadeshi (indigenous) products and the cause of Swaraj (Self-rule) for India. In 1923, at an age of 35, he became the youngest person to serve as the President of the Indian National Congress.

In October 1920, Azad was elected as a member of foundation committee to establish Jamia Millia Islamia at Aligarh in U. P. without taking help from British colonial government. He assisted in shifting the campus of the university from Aligarh to New Delhi in 1934. The main gate (Gate No. 7) to the main campus of the university is named after him.

Azad was one of the main organizers of the Dharasana Satyagraha in 1931, and emerged as one of the most important national leaders of the time, prominently leading the causes of Hindu–Muslim unity as well as espousing secularism and socialism. He served as Congress president from 1940 to 1945, during which the Quit India rebellion was launched. Azad was imprisoned, together with the entire Congress leadership. He also worked for Hindu–Muslim unity through the Al-Hilal newspaper.[4]

BiographyEdit

Early lifeEdit

Azad was born on 11 November 1888 in Mecca, then a part of the Ottoman Empire, now a part of Saudi Arabia. His real name was Sayyid Ghulam Muhiyuddin Ahmed bin Khairuddin Al Hussaini, but he eventually became known as Maulana Abul Kalam Azad.[5] Azad's father was a Muslim scholar of Afghan ancestry, who lived in Delhi with his maternal grandfather, as his father had died at a very young age.[6] During the Indian Rebellion of 1857, he left India and settled in Mecca. His father Muhammad Khairuddin bin Ahmed Al Hussaini wrote twelve books, had thousands of disciples, and claimed noble ancestry,[7] while his mother was Sheikha Alia bint Mohammad, the daughter of Sheikh Mohammad bin Zaher AlWatri, himself a reputed scholar from Medina who had a reputation that extended even outside of Arabia.[5][6]

Azad settled in Calcutta with his family in 1890.[8][9]

Education and influencesEdit

Azad was home-schooled and self-taught.[10] Following fluency in Arabic as a first language, Azad began to master several other languages including Bengali, Hindustani, Persian, and English.[5] He was also trained in the Mazahibs of Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi'i and Hanbali fiqh, Shariat, mathematics, philosophy, world history, and science by tutors hired by his family. An avid and determined student, the precocious Azad was running a library, a reading room, and a debating society before he was twelve; wanted to write on the life of Al-Ghazali at twelve; was contributing learned articles to Makhzan (a literary magazine) at fourteen;[11] was teaching a class of students, most of whom were twice his age, when he was fifteen; and completed the traditional course of study at the age of sixteen, nine years ahead of his contemporaries, and brought out a magazine at the same age.[12] At the age of thirteen, he was married to a young Muslim girl, Zulaikha Begum.[9] Azad compiled many treatises interpreting the Qur'an, the Hadis, and the principles of Fiqh and Kalam.[8]

Early journalistic careerEdit

Azad began his journalistic endeavours at an early age. In 1899 at the age of eleven he started publishing a poetical journal Nairang-e-Aalam at Calcutta and was already an editor of a weekly Al-Misbah in 1900.[13] He contributed articles to Urdu magazines and journals such as Makhzan, Ahsanul Akhbar, and Khadang e Nazar.[14]

In 1903, he brought out a monthly journal, Lissan-us-Sidq. It was published between December 1903 to May 1905 until its closure due to shortage of funds.[15] He then joined Al Nadwa, the Islamic theological journal of the Nadwatu l-Ulama on Shibli Nomani’s invitation.[16] He worked as editor of Vakil, a newspaper from Amritsar from April 1906 to November 1906. He shifted to Calcutta for a brief period where he was associated with Dar-ul-Saltunat. He returned to Amritsar after few months and resumed the editorship of Vakil, continuing to work there until July 1908.[17]

Struggle for Indian IndependenceEdit

In 1908, he took a trip of Egypt, Syria, Turkey and France where he came into contact with several revolutionaries such as followers of Kamal Mustafa Pasha, members of Young Turk Movement and Iranian revolutionaries.[18] Azad developed political views considered radical for most Muslims of the time and became a full-fledged Indian nationalist.[8] In his writing, Azad proved to be a fierce critic of both the British government and Muslim politicians; the former for its racial discrimination and refusal to provide for the needs of the Indian public, and the later for focusing on communal issues before matter of common-self interest (Azad pointedly rejected the All-India Muslim League's communal separatism). However, his views changed considerably when he met ethnically-oriented Sunni revolutionary activists in Iraq[19] and was influenced by their fervent anti-imperialism and Arab nationalism.[8] Against common Muslim opinion of the time, Azad opposed the partition of Bengal in 1905 and became increasingly active in revolutionary activities, to which he was introduced by the prominent Hindu revolutionaries Aurobindo Ghosh and Shyam Sundar Chakravarty. Azad initially evoked surprise from other revolutionaries, but Azad won their praise and confidence by working secretly to organise revolutionaries activities and meetings in Bengal, Bihar and Bombay (now called Mumbai).[8]

Al-Hilal and Khilafat movementEdit

He established an Urdu weekly newspaper in 1912 called Al-Hilal from Calcutta, and openly attacked British policies while exploring the challenges facing common people. Espousing the ideals of Indian nationalism, Azad's publications were aimed at encouraging young Muslims into fighting for independence and Hindu-Muslim unity.[20] With the onset of World War I, the British stiffened censorship and restrictions on political activity. Azad's Al-Hilal was consequently banned in 1914 under the Press Act.[21]

In 1913, he was founding member of the Anjuman-i-Ulama-i-Bangala, which would become the Jamiat Ulema-e-Bangala branch of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind in 1921. His work helped improve the relationship between Hindus and Muslims in Bengal, which had been soured by the controversy surrounding the partition of Bengal and the issue of separate communal electorates.

In this period Azad also became active in his support for the Khilafat agitation to protect the position of the Sultan of Ottoman Turkey, who was considered the Caliph or Khalifa for Muslims worldwide. The Sultan had sided against the British in the war and the continuity of his rule came under serious threat, causing distress amongst Muslim conservatives. Azad saw an opportunity to energise Indian Muslims and achieve major political and social reform through the struggle.

Azad started a new journal, the Al-Balagh, which also got banned in 1916[22] under the Defence of India Regulations Act and he was arrested. The governments of the Bombay Presidency, United Provinces, Punjab and Delhi prohibited his entry into the provinces and Azad was moved to a jail in Ranchi, where he was incarcerated until 1 January 1920.[23]

Non-co-operation MovementEdit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2021) |

Upon his release, Azad returned to a political atmosphere charged with sentiments of outrage and rebellion against British rule. The Indian public had been angered by the passage of the Rowlatt Acts in 1919, which severely restricted civil liberties and individual rights. Consequently, thousands of political activists had been arrested and many publications banned. The killing of unarmed civilians at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar on 13 April 1919 had provoked intense outrage all over India, alienating most Indians, including long-time British supporters, from the authorities. The Khilafat struggle had also peaked with the defeat of the Ottoman Empire in World War I and the raging Turkish War of Independence, which had made the caliphate's position precarious. India's main political party, the Indian National Congress came under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, who had aroused excitement all over India when he led the farmers of Champaran and Kheda in a successful revolt against British authorities in 1918. Gandhi organised the people of the region and pioneered the art of Satyagraha— combining mass civil disobedience with complete non-violence and self-reliance.

Taking charge of the Congress, Gandhi also reached out to support the Khilafat struggle, helping to bridge Hindu-Muslim political divides. Azad and the Ali brothers – Maulana Mohammad Ali and Shaukat Ali – warmly welcomed Congress support and began working together on a programme of non-co-operation by asking all Indians to boycott British-run schools, colleges, courts, public services, the civil service, police and military. Non-violence and Hindu-Muslim unity were universally emphasised, while the boycott of foreign goods, especially clothes were organised. Azad joined the Congress and was also elected president of the All India Khilafat Committee. Although Azad and other leaders were soon arrested, the movement drew out millions of people in peaceful processions, strikes and protests.

This period marked a transformation in Azad's own life. Along with fellow Khilafat leaders Mukhtar Ahmad Ansari, Hakim Ajmal Khan and others, Azad grew personally close to Gandhi and his philosophy. The three men founded the Jamia Millia Islamia in Delhi as an institution of higher education managed entirely by Indians without any British support or control. Both Azad and Gandhi shared a deep passion for religion and Azad developed a close friendship with him. He adopted the Islamic prophet Muhammad's ideas by living simply, rejecting material possessions and pleasures. He began to spin his own clothes using khadi on the charkha, and began frequently living and participating in the ashrams organised by Gandhi.[citation needed] Becoming deeply committed to ahimsa (non-violence) himself, Azad grew close to fellow nationalists like Jawaharlal Nehru, Chittaranjan Das and Subhas Chandra Bose.[23] He strongly criticised the continuing suspicion of the Congress amongst the Muslim intellectuals from the Aligarh Muslim University and the Muslim League.

In 1921, he started the weekly Paigham which was also banned by December 1921.[24] He along with the editor of Paigham, Abdul Razzak Mahilabadi was arrested by the government[25] and sentenced to one year imprisonment.[26]

During the course of 1922, both the Khilafat and the non cooperation movement suffered blow while Azad and other leaders like the Ali brothers were in jail.[27] The movement had a sudden decline with rising incidences of violence; a nationalist mob killed 22 policemen in Chauri Chaura in 1922. Fearing degeneration into violence, Gandhi asked Indians to suspend the revolt and undertook a five-day fast to repent and encourage others to stop the rebellion. Although the movement stopped all over India, several Congress leaders and activists were disillusioned with Gandhi. The following year, the caliphate was overthrown by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the Ali brothers grew distant and critical of Gandhi and the Congress. Azad's close friend Chittaranjan Das co-founded the Swaraj Party, breaking from Gandhi's leadership. Despite the circumstances, Azad remained firmly committed to Gandhi's ideals and leadership.

In 1923, he became the youngest man to be elected Congress president. Azad led efforts to organise the Flag Satyagraha in Nagpur. Azad served as president of the 1924 Unity Conference in Delhi, using his position to work to re-unite the Swarajists and the Khilafat leaders under the common banner of the Congress. In the years following the movement, Azad travelled across India, working extensively to promote Gandhi's vision, education and social reform.

Congress leaderEdit

Azad became an inspiring personality in the field of politics. Azad became an important national leader, and served on the Congress Working Committee and in the offices of general secretary and president many times. The political environment in India re-energised in 1928 with nationalist outrage against the Simon Commission appointed to propose constitutional reforms. The commission included no Indian members and did not even consult Indian leaders and experts. In response, the Congress and other political parties appointed a commission under Motilal Nehru to propose constitutional reforms from Indian opinions. In 1928, Azad endorsed the Nehru Report, which was criticised by the Ali brothers and Muslim League politician Muhammad Ali Jinnah. Azad endorsed the ending of separate electorates based on religion, and called for an independent India to be committed to secularism. At the 1928 Congress session in Guwahati, Azad endorsed Gandhi's call for dominion status for India within a year. If not granted, the Congress would adopt the goal of complete political independence for India. Despite his affinity for Gandhi, Azad also drew close to the young radical leaders Jawaharlal Nehru and Subhash Bose, who had criticised the delay in demanding full independence. Azad developed a close friendship with Nehru and began espousing socialism as the means to fight inequality, poverty and other national challenges. Azad decided the name of Muslim political party Majlis-e-Ahrar-ul-Islam. He was also a friend of Syed Ata Ullah Shah Bukhari, founder of All India Majlis-e-Ahrar. When Gandhi embarked on the Dandi Salt March that inaugurated the Salt Satyagraha in 1930, Azad organised and led the nationalist raid, albeit non-violent on the Dharasana salt works to protest the salt tax and restriction of its production and sale. The biggest nationalist upheaval in a decade, Azad was imprisoned along with millions of people, and would frequently be jailed from 1930 to 1934 for long periods of time. Following the Gandhi–Irwin Pact in 1931, Azad was amongst millions of political prisoners released. When elections were called under the Government of India Act 1935, Azad was appointed to organise the Congress election campaign, raising funds, selecting candidates and organising volunteers and rallies across India.[23] Azad had criticised the Act for including a high proportion of un-elected members in the central legislature, and did not himself contest a seat. He again declined to contest elections in 1937, and helped head the party's efforts to organise elections and preserve co-ordination and unity amongst the Congress governments elected in different provinces.[23]

At the 1936 Congress session in Lucknow, Azad was drawn into a dispute with Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, Dr. Rajendra Prasad and C. Rajagopalachari regarding the espousal of socialism as the Congress goal. Azad had backed the election of Nehru as Congress president, and supported the resolution endorsing socialism. In doing so, he aligned with Congress socialists like Nehru, Subhash Bose and Jayaprakash Narayan. Azad also supported Nehru's re-election in 1937, at the consternation of many conservative Congressmen. Azad supported dialogue with Jinnah and the Muslim League between 1935 and 1937 over a Congress-League coalition and broader political co-operation. Less inclined to brand the League as obstructive, Azad nevertheless joined the Congress's vehement rejection of Jinnah's demand that the League be seen exclusively as the representative of Indian Muslims.

Quit India MovementEdit

In 1938, Azad served as an intermediary between the supporters of and the Congress faction led by Congress president Subhash Bose, who criticised Gandhi for not launching another rebellion against the British and sought to move the Congress away from Gandhi's leadership. Azad stood by Gandhi with most other Congress leaders, but reluctantly endorsed the Congress's exit from the assemblies in 1939 following the inclusion of India in World War II. Nationalists were infuriated that Viceroy Lord Linlithgow had entered India into the war without consulting national leaders. Although willing to support the British effort in return for independence, Azad sided with Gandhi when the British ignored the Congress overtures. Azad's criticism of Jinnah and the League intensified as Jinnah called Congress rule in the provinces as "Hindu Raj", calling the resignation of the Congress ministries as a "Day of Deliverance" for Muslims. Jinnah and the League's separatist agenda was gaining popular support amongst Muslims. Muslim religious and political leaders criticised Azad as being too close to the Congress and placing politics before Muslim welfare.[23] As the Muslim League adopted a resolution calling for a separate Muslim state (Pakistan) in its session in Lahore in 1940, Azad was elected Congress president in its session in Ramgarh. Speaking vehemently against Jinnah's Two-Nation Theory—the notion that Hindus and Muslims were distinct nations—Azad lambasted religious separatism and exhorted all Muslims to preserve a united India, as all Hindus and Muslims were Indians who shared deep bonds of brotherhood and nationhood. In his presidential address, Azad said:

" Full eleven centuries have passed by since then. Islam has now as great a claim on the soil of India as Hinduism. If Hinduism has been the religion of the people here for several thousands of years, Islam also has been their religion for a thousand years. Just as a Hindu can say with pride that he is an Indian and follows Hinduism, so also we can say with equal pride that we are Indians and follow Islam. I shall enlarge this orbit still further. The Indian Christian is equally entitled to say with pride that he is an Indian and is following a religion of India, namely Christianity."[23]

In face of increasing popular disenchantment with the British across India, Gandhi and Patel advocated an all-out rebellion demanding immediate independence. Azad was wary and sceptical of the idea, aware that India's Muslims were increasingly looking to Jinnah and had supported the war. Feeling that a struggle would not force a British exit, Azad and Nehru warned that such a campaign would divide India and make the war situation even more precarious. Intensive and emotional debates took place between Azad, Nehru, Gandhi and Patel in the Congress Working Committee's meetings in May and June 1942. In the end, Azad became convinced that decisive action in one form or another had to be taken, as the Congress had to provide leadership to India's people and would lose its standing if it did not.

Supporting the call for the British to "Quit India", Azad began exhorting thousands of people in rallies across the nation to prepare for a definitive, all-out struggle. As Congress president, Azad travelled across India and met with local and provincial Congress leaders and grass-roots activists, delivering speeches and planning the rebellion. Despite their previous differences, Azad worked closely with Patel and Dr. Rajendra Prasad to make the rebellion as effective as possible. On 7 August 1942 at the Gowalia Tank in Mumbai, Congress president Azad inaugurated the struggle with a vociferous speech exhorting Indians into action. Just two days later, the British arrested Azad and the entire Congress leadership. While Gandhi was incarcerated at the Aga Khan Palace in Pune, Azad and the Congress Working Committee were imprisoned at a fort in Ahmednagar, where they would remain under isolation and intense security for nearly four years. Outside news and communication had been largely prohibited and completely censored. Although frustrated at their incarceration and isolation, Azad and his companions attested to feeling a deep satisfaction at having done their duty to their country and people.[28]

Azad occupied the time playing bridge and acting as the referee in tennis matches played by his colleagues. In the early mornings, Azad began working on his classic Urdu work, the Ghubhar-i-Khatir. Sharing daily chores, Azad also taught the Persian and Urdu languages, as well as Indian and world history to several of his companions. The leaders would generally avoid talking of politics, unwilling to cause any arguments that could exacerbate the pain of their imprisonment. However, each year on 26 January, which was then considered Poorna Swaraj (Complete Independence) Day, the leaders would gather to remember their cause and pray together. Azad, Nehru and Patel would briefly speak about the nation and the future. Azad and Nehru proposed an initiative to forge an agreement with the British in 1943. Arguing that the rebellion had been mistimed, Azad attempted to convince his colleagues that the Congress should agree to negotiate with the British and call for the suspension of disobedience if the British agreed to transfer power. Although his proposal was overwhelmingly rejected, Azad and a few others agreed that Gandhi and the Congress had not done enough. When they learnt of Gandhi holding talks with Jinnah in Mumbai in 1944, Azad criticised Gandhi's move as counter-productive and ill-advised.[29]

Partition of IndiaEdit

With the end of the war, the British agreed to transfer power to Indian hands. All political prisoners were released in 1946 and Azad led the Congress in the elections for the new Constituent Assembly of India, which would draft India's constitution. He headed the delegation to negotiate with the British Cabinet Mission, in his sixth year as Congress president. While attacking Jinnah's demand for Pakistan and the mission's proposal of 16 June 1946 that envisaged the partition of India, Azad became a strong proponent of the mission's earlier proposal of 16 May. The proposal advocated a federal system with a limited central government and autonomy for the provinces. The central government would have Defence, Foreign Affairs and Communication while the provinces would win all other subjects unless they voluntarily relinquished selected subjects to the Central Government. Additionally, the proposal called for the "grouping" of provinces on religious lines, which would informally band together the Muslim-majority provinces in the West as Group B, Muslim-majority provinces of Bengal and Assam as Group C and the rest of India as Group A. While Gandhi and others expressed scepticism of this clause, Azad argued that Jinnah's demand for Pakistan would be buried and the concerns of the Muslim community would be assuaged.[30] Under Azad and Patel's backing,[citation needed] the Working Committee approved the resolution against Gandhi's advice. Azad also managed to win Jinnah's agreement to the proposal citing the greater good of all Indian Muslims.[6]

Azad had been the Congress president since 1939, so he volunteered to resign in 1946. He nominated Nehru, who replaced him as Congress president and led the Congress into the interim government. Azad was appointed to head the Department of Education. However, Jinnah's Direct Action Day agitation for Pakistan, launched on 16 August sparked communal violence across India. Thousands of people were killed as Azad travelled across Bengal and Bihar to calm the tensions and heal relations between Muslims and Hindus. Despite Azad's call for Hindu-Muslim unity, Jinnah's popularity amongst Muslims soared and the League entered a coalition with the Congress in December, but continued to boycott the constituent assembly. Later in his autobiography, Azad indicated Patel having become more pro-partition than the Muslim League, largely due to the League's not co-operating with the Congress in the provisional government on any issue.[6]

Azad had grown increasingly hostile to Jinnah, who had described him as the "Muslim Lord Haw-Haw" and a "Congress Showboy."[31][32] Muslim League politicians accused Azad of allowing Muslims to be culturally and politically dominated by the Hindu community. Azad continued to proclaim his faith in Hindu-Muslim unity:[33]

"I am proud of being an Indian. I am part of the indivisible unity that is Indian nationality. I am indispensable to this noble edifice and without me this splendid structure is incomplete. I am an essential element, which has gone to build India. I can never surrender this claim."

Amidst more incidences of violence in early 1947, the Congress-League coalition struggled to function. The provinces of Bengal and Punjab were to be partitioned on religious lines, and on 3 June 1947 the British announced a proposal to partition India on religious lines, with the princely states free to choose between either dominion. The proposal was hotly debated in the All India Congress Committee, with Muslim leaders Saifuddin Kitchlew and Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan expressing fierce opposition. Azad privately discussed the proposal with Gandhi, Patel and Nehru, but despite his opposition was unable to deny the popularity of the League and the unworkability of any coalition with the League. Faced with the serious possibility of a civil war, Azad abstained from voting on the resolution, remaining silent and not speaking throughout the AICC session, which ultimately approved the plan.[34]

Azad, committed to a united India until his last attempt, was condemned by the advocates of Pakistan, especially the Muslim League.[35]

Post-Independence careerEdit

India's partition and independence on 15 August 1947 brought with it a scourge of violence that swept the Punjab, Bihar, Bengal, Delhi and many other parts of India. Millions of Hindus and Sikhs fled the newly created Pakistan for India, and millions of Muslims fled for West Pakistan and East Pakistan, created out of East Bengal. Violence claimed the lives of an estimated one million people, almost entirely in Punjab. Azad took up responsibility for the safety of Muslims in India, touring affected areas in Bengal, Bihar, Assam and the Punjab, guiding the organisation of refugee camps, supplies and security. Azad gave speeches to large crowds encouraging peace and calm in the border areas and encouraging Muslims across the country to remain in India and not fear for their safety and security. Focusing on bringing the capital of Delhi back to peace, Azad organised security and relief efforts, but was drawn into a dispute with the Deputy prime minister and Home Minister Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel when he demanded the dismissal of Delhi's police commissioner, who was a Sikh accused by Muslims of overlooking attacks and neglecting their safety.[36] Patel argued that the commissioner was not biased, and if his dismissal was forced it would provoke anger amongst Hindus and Sikhs and divide the city police. In Cabinet meetings and discussions with Gandhi, Patel and Azad clashed over security issues in Delhi and Punjab, as well as the allocation of resources for relief and rehabilitation. Patel opposed Azad and Nehru's proposal to reserve the houses vacated by Muslims who had departed for Pakistan for Muslims in India displaced by the violence.[36] Patel argued that a secular government could not offer preferential treatment for any religious community, while Azad remained anxious to assure the rehabilitation of Muslims in India, secularism, religious freedom and equality for all Indians. He supported provisions for Muslim citizens to make avail of Muslim personal law in courts.[37]

Azad remained a close confidante, supporter and advisor to prime minister Nehru, and played an important role in framing national policies. Azad masterminded the creation of national programmes of school and college construction and spreading the enrolment of children and young adults into schools, to promote universal primary education. Elected to the lower house of the Indian Parliament, the Lok Sabha in 1952 from Rampur district cum Bareilly district West Lok Sabha seat and again in 1957, Azad supported Nehru's socialist economic and industrial policies, as well as the advancing social rights and economic opportunities for women and underprivileged Indians. In 1956, he served as president of the UNESCO General Conference held in Delhi. Azad spent the final years of his life focusing on writing his book India Wins Freedom, an exhaustive account of India's freedom struggle and its leaders, which was published in 1959.

As India's first Minister of Education, he emphasised on educating the rural poor and girls. As Chairman of the Central Advisory Board of Education, he gave thrust to adult literacy, universal primary education, free and compulsory for all children up to the age of 14, girl's education, and diversification of secondary education and vocational training.[38] Addressing the conference on All India Education on 16 January 1948, Maulana Azad emphasised,[38]

We must not for a moment forget, it is a birthright of every individual to receive at least the basic education without which he cannot fully discharge his duties as a citizen.

He oversaw the setting up of the Central Institute of Education, Delhi, which later became the Department of Education of the University of Delhi as "a research centre for solving new educational problems of the country".[39] Under his leadership, the Ministry of Education established the first Indian Institute of Technology in 1951 and the University Grants Commission in 1953.,[40][41] He also laid emphasis on the development of the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore and the Faculty of Technology of the Delhi University.[42] He foresaw a great future in the IITs for India:[42]

I have no doubt that the establishment of this Institute will form a landmark in the progress of higher technological education and research in the country.

Literary worksEdit

Azad wrote many books including India Wins Freedom, Ghubar-e-Khatir, Tazkirah, Tarjumanul Quran (Urdu تذکرہ ترجمان القُران), etc.

Ghubar-e-KhatirEdit

Ghubar-e-Khatir (Sallies of Mind), (Urdu: غُبارِخاطِر) is one of the most important works of Azad, written primarily during 1942 to 1946 when he was imprisoned in Ahmednagar Fort in Maharashtra by British Raj while he was in Bombay (now Mumbai) to preside over the meeting of All India Congress Working Committee.[35]

The book is basically a collection of 24 letters he wrote addressing his close friend Maulana Habibur Rahman Khan Sherwani. These letters were never sent to him because there was no permission for that during the imprisonment and after the release in 1946, he gave all these letters to his friend Ajmal Khan who let it published for the first time in 1946.

Although the book is a collection of letters but except one or two letters, all other letters are unique and most of the letters deal with complex issues such as existence of God,[43] the origin of religions, the origin of music and its place in religion, etc.

The book is primarily an Urdu language book; however, there are over five hundred of couplets, mostly in Persian and Arabic languages. It is because, Maulana was born in a family where Arabic and Persian were used more frequently than Urdu. He was born in Mekkah, given formal education in Persian and Arabic languages but he was never taught Urdu.

It is often said that his book India Wins Freedom is about his political life and Ghubar-e-Khatir deals with his social and spiritual life.[44]

Legacy and influenceEdit

The Ministry of Minority Affairs of the central Government of India set up the Maulana Azad Education Foundation in 1989 on the occasion of his birth centenary to promote education amongst educationally backward sections of the Society.[45] The Ministry also provides the Maulana Abul Kalam Azad National Fellowship, an integrated five-year fellowship in the form of financial assistance to students from minority communities to pursue higher studies such as M. Phil and PhD[46] In 1992 government of India honoured by giving posthumously Bharat Ratna.[47]

Numerous institutions across India have also been named in his honour. Some of them are the Maulana Azad Medical College in New Delhi, the Maulana Azad National Institute of Technology in Bhopal, the Maulana Azad National Urdu University in Hyderabad, Maulana Azad Centre for Elementary and Social Education (MACESE Delhi University), the Maulana Azad College, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies, and Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, in Kolkata, Bab – e – Maulana Abul Kalam Azad (Gate No. 7), Jamia Millia Islamia, A Central (Minority) University in New Delhi, the Maulana Azad library in the Aligarh Muslim University in Aligarh and Maulana Azad Stadium in Jammu. His home housed the Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies earlier, and is now the Maulana Azad Museum.[48] National Education Day (India) an annual observance in India to commemorate the birth anniversary of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the first education minister of independent India, who served from 15 August 1947 until 2 February 1958. National Education Day of India is celebrated on 11 November every year in India.

He is celebrated as one of the founders and greatest patrons of the Jamia Millia Islamia. Azad's tomb is located next to the Jama Masjid in Delhi. In recent years great concern has been expressed by many in India over the poor maintenance of the tomb.[35] On 16 November 2005 the Delhi High Court ordered that the tomb of Maulana Azad in New Delhi be renovated and restored as a major national monument. Azad's tomb is a major landmark and receives large numbers of visitors annually.[49]

Jawaharlal Nehru referred to him as Mir-i- Karawan (the caravan leader), "a very brave and gallant gentleman, a finished product of the culture that, in these days, pertains to few".[35] Mahatma Gandhi remarked about Azad by counting him as "a person of the calibre of Plato, Aristotle and Pythagorus".[38]

Azad was portrayed by actor Virendra Razdan in the 1982 biographical film, Gandhi, directed by Richard Attenborough.[50]

A television series, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, aired on DD National in the 1990s and starred Mangal Dhillon in the titular role.[51][52] DD Urdu aired Seher Hone Tak, a docudrama television series by Lavlin Thadani based on his life and political career, with Aamir Bashir portraying the role of Azad. It was later shortened and re-released as the film Aashiq-e-Vatan - Maulana Azad.[53] Woh Jo Tha Ek Massiah Maulana Azad, a 2019 biographical film about Azad was directed by Rajendra Gupta Sanjay and Sanjay Singh Negi, with Linesh Fanse playing the titular role.[54]

His birthday, 11 November is celebrated as National Education Day in India.[55]

See alsoEdit

- Cyrus the Great as Dhul-Qarnayn, a theory first proposed by Azad

- Indian Council for Cultural Relations, international cultural promotion organization founded by Azad

ReferencesEdit

- ↑ Fahad, Obaidullah (2011). "Tracing Pluralistic Trends in Sīrah Literature: A Study of Some Contemporary Scholars". Islamic Studies. 50 (2): 238. JSTOR 41932590.

- ↑ "International Urdu conference from Nov. 10". The Hindu. 7 November 2010. Archived from the original on 11 November 2010. Retrieved 13 April 2012.

- ↑ Chawla, Muhammad (2016). "Maulana Azad and the Demand for Pakistan: A Reappraisal". Journal of the Pakistan Historical Society. 64 (3): 7–24.

- ↑ "Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Biography – Maulana Azad Indian Freedom Fighter – Information on Maulana Azad – History of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad". www.iloveindia.com. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 "Remembering Maulana Abul Kalam Azad: A Short Biography". Institute of Asian Studies. Retrieved 1 January 2013.

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad was born on November 11, 1888, in Mecca. He came back to Calcutta with his family in 1890.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Azad, Abul Kalam (2003) [First published 1959]. India Wins Freedom: An Autobiographical Narrative. New Delhi: Orient Longman. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-81-250-0514-8.

- ↑ Biography Of Maulana Azad. Iccrindia.net. Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Sirajul Islam (2012). "Azad, Maulana Abul Kalam". In Islam, Sirajul; Miah, Sajahan; Khanam, Mahfuza; Ahmed, Sabbir (eds.). Banglapedia: the National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Online ed.). Dhaka, Bangladesh: Banglapedia Trust, Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. ISBN 984-32-0576-6. OCLC 52727562. Retrieved 19 June 2025.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gandhi, Rajmohan (1986). Eight Lives: A Study of the Hindu-Muslim Encounter. USA: State University of New York Press. p. 219. ISBN 978-0-88706-196-7.

- ↑ Ayoob, Mohammed (25 May 2018) Remembering Maulana Azad. The Hindu. Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ↑ Ikram, S. M. (1995). Indian Muslims and Partition of India. Atlantic Publishers and Distributors. p. 139. ISBN 9788171563746

- ↑ Maulana Abul Kalam Azad – The Builder of Modern India. Indiaedunews.net (11 November 2008). Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 678

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 678

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 678, 679

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 679

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 679, 680

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 680

- ↑ Osmani, Ahmed. Maulana Azad's Political History. pp. 67–85

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 680, 681

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 683

- ↑ Qaiyoom 2012, pp. 683

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 23.4 23.5 Huq, Mushirul (23 July 2006). "President Azad". Archived from the original (PHP) on 9 April 2009. Retrieved 23 July 2006.

- ↑ Pant 2010, pp. 1314

- ↑ Douglas 1993, pp. 180

- ↑ Douglas 1993, pp. 189

- ↑ Douglas 1993, pp. 190

- ↑ Nandurkar. Sardarshri Ke Patra (2). p. 390.

- ↑ Gandhi, pp. 330–32

- ↑ Menon, V. P. (1998). Transfer of Power in India. Orient Blackswan. p. 235. ISBN 9788125008842.

- ↑ Azad (2007). The Elephant, the Tiger and the Cellphone: Reflections on India in the Twenty-first Century. Penguin India. ISBN 9780670081455.

- ↑ "The man who stayed behind". The Hindu. 11 November 2007. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

- ↑ Hasan, Mushirul (January 2000). "One hundred people who shaped India in the 20th century, Maulana Abul Kalam Azad – II". India Today, special millennium issue, January 2000. Archived from the original (PHP) on 22 November 2008. Retrieved 14 June 2007.

- ↑ Gandhi, p. 402

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 Azad, Abul Kalam (2010). Ghubar-e-Khatir. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 5,7. ISBN 978-81-260-0132-3.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Gandhi, pp. 432–33

- ↑ Gandhi, pp. 502–05

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Speech of Hon’ble Human Resource Minister on National Education Day 2009, Ministry of HRD, Government of India Archived 7 October 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "About us Central Institute of Education". Archived from the original on 5 March 2012. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ↑ UGC Genesis Archived 6 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ IIT Kharagpur, History Archived 13 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Proceedings of the 19th meeting of The Central Advisory Board of Education, New Delhi on 15 and 16 March 1952 Archived 16 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Azad, Abul Kalam (2010). Ghubar-e-Khatir. New Delhi: Sahitya Akademi. p. 106. ISBN 978-81-260-0132-3.

- ↑ Douglas, Ian H. (1972). ""Abul Kalam Azad and Pakistan" A Post-Bangladesh Reconsideration of an Indian Muslim's Opposition to Partition". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 40 (4): 458–479. doi:10.1093/jaarel/XL.4.458. JSTOR 1460895.

- ↑ Maulana Azad Education Foundation website. Maef.nic.in. Retrieved on 7 December 2018.

- ↑ Shri Salman Khurshid Launches Maulana Abul Kalam Azad National Fellowship, Press Information Bureau, Government of India, 22 December 2009.

- ↑ "National Education Day celebrated". The Hindu. Krishnagiri. 14 November 2011. Archived from the original on 25 March 2014. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Sharma, Arun Kumar (7 November 2010). "Visionary educationist". The Tribune. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- ↑ "Maulana Abul Kalam Azad Institute of Asian Studies --- Museum". makaias.gov.in. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

- ↑ "Restore Maulana Azad's grave: HC". Express News Service, Expressindia.com. 17 November 2005. Archived from the original (PHP) on 4 December 2007. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

- ↑ "Virendra Razdan dead". The Deccan Herald, The Free Press Journal. Ministry of Information and Broadcasting (India) Bulletin on Film Volume XLVII No. 6. 15 June 2003. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ↑ Mazahir Rahim (21 April 2016). "Maulana Abul Kalam Azad - Ep 1". YouTube. Archived from the original on 22 December 2021.

- ↑ National Film Festival. Directorate of Film Festivals. 1993. p. 125.

- ↑ "Aashiq-e -Vatan Maulana Azad". Explara.com.

- ↑ Purkayastha, Pallabi Dey (18 January 2019). "Woh Jo Tha Ek Massiah Maulana Azad Movie Review {2.5/5}". Times of India.

- ↑ "Maulana Abul Kalam Azad remembered on National Education Day". The Indian Express. 12 November 2008. Retrieved 8 November 2019.

Cited sourcesEdit

- Gandhi, R (1990). Patel: A Life. Navajivan, Ahmedabad.

- Pant, Vijay Prakash (2010). "MAULANA ABUL KALAM AZAD: A Critical Analysis Life and Work". The Indian Journal of Political Science. 71 (4): 1311–1323. ISSN 0019-5510. JSTOR 42748956.

- Qaiyoom, Nishat (2012). "Maulana Azad's Journalistic Crusade Against Colonialism". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 73: 678–685. ISSN 2249-1937. JSTOR 44156263.

- Douglas, Ian Henderson (1993). Abul Kalam Azad: An Intellectual and Religious Biography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-563279-8.

Further readingEdit

- Ashraf, Muhammad Arslan. Why Partition of India?: Gandhi, Jinnah, Nehru, Azad - Congress and Muslim League (2016) online , 20pp

- Maulana Azad's commentary on the Holy Qur'an – Tarjuman al-Quran

- Die politische Willensbildung in Indien 1900–1960; 1965 von Dietmar Rothermund

- Life and Works of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, from Ravindra Kumar, published by Atlantic Publishers & Distributors, 1991

- Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, by Mahadev Haribhai Desai

- The Educational Ideas of Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, by G. Rasool Abduhu, published by Sterling Publishers, 1973

- India's Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, by Abulkalam Azad, Syeda Saiyidain Hameed, Mujib Rizvi, Sughra Mahdi, published by Indian Council for Cultural Relations, 1990

- Maulana Azad ek Muttala by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Jawahar aur Azad, Edited by Professor Abdul Qavi Desnavi, Saifia College, Bhopal, 1990.

- Maulana Azad Aur Bhopal by Hakim Syed Zillur Rahman, Fikro Nazar (Maulana Azad Number), Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 1989, p. 107–112.

- Pattabhi, Sitaramayya (1946). Feathers & Stones "my study windows". Padma Publications.

- Nandurkar, G. M. (1981). Sardar's letters, mostly unknown. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel Smarak Bhavan.

- "Brief sketch of life and thinking of Maulana Azad". Liveindia.com.

- "Life of Azad". CIS-CA. Archived from the original on 19 April 2003. Retrieved 26 November 2005.

- "Maulana Abul Kalam Azad: The Odd Secularist". India Today. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 6 November 2006.

External linksEdit

- Abul Kalam Azad at Encyclopædia Britannica

- APJ Abdul Kalam Scholarship Archived 30 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- Azad's Careers – Roads taken and roads not taken – Lineages of the Present: Ideology and Politics in Contemporary South Asia By Aijaz Ahmad

- An Introduction to Abul Kalam Azad & collection of his quotes – Eminent Indian freedom fighters Vol2 Chapter 11 p. 310 By S.K. Sharma

- Abu'l Kalam Azad, Chapter 44, pp. 325–333, Modernist Islam, 1840–1940: a sourcebook By Charles Kurzman

- National Education Day 2012 Celebrated at Sangam University Bhilwara Rajasthan