Indian Navy

Thank you for being part of the Bharatpedia family! 0% transparency: ₹0 raised out of ₹100,000 (0 supporter) |

The Indian Navy is the naval part of the Indian Armed Forces.

In 2010, the Indian Navy had 58,350 personnel, around 170 ships and 180 aircraft.[1] It is the world's fourth largest navy in terms of personnel.

The Indian Navy traces its origins back to the East India Company's Marine which was founded in 1612 to protect British merchant shipping in the region. In 1793, the British East India Company established its rule over eastern part of the Indian subcontinent i.e. Bengal, but it was not until 1830 that the colonial navy was titled as His Majesty's Indian Navy. When India became a republic in 1950, the Royal Indian Navy as it had been named since 1934 was renamed to Indian Navy.

The primary objective of the navy is to safeguard the nation's maritime borders, and in conjunction with other Armed Forces of the union, act to deter or defeat any threats or aggression against the territory, people or maritime interests of India, both in war and peace. Through joint exercises, goodwill visits and humanitarian missions, including disaster relief, Indian Navy promotes bilateral relations between nations.

As of June 2019, Indian Navy has 67,252 active[2] and 55,000 reserve personnel in service and has a fleet of 150 ships and submarines, and 300 aircraft.[3][4]As of October 2020, the operational fleet consists of 1 aircraft carrier active and 1 more on sea trials, 1 amphibious transport dock, 8 landing ship tanks, 10 destroyers, 14 frigates, 1 nuclear-powered attack submarine, 1 ballistic missile submarine, 15 conventionally-powered attack submarines and more on sea trials, 24 corvettes, one mine countermeasure vessel, 4 fleet tankers and numerous other auxiliary vessels, small patrol boats and sophisticated ships. It is considered as a multi-regional power projection blue-water navy.[5][6]

History

Early maritime history

The maritime history of India dates back to 6,000 years with the birth of art of the navigation and navigating during the Indus Valley Civilisation.[7] A Kutch mariner's log book from 19th century recorded that the first tidal dock India has been built at Lothal around 2300 BC during the Indus Valley Civilisation, near the present day harbour of Mangrol on the Gujarat coast. The Rig Veda, credits Varuna, the Hindu god of water and the celestial ocean,[8] with knowledge of the ocean routes and describes the use of ships having hundred oars in the naval expeditions by Indians. There are also references to the side wings of a ship called Plava, which stabilizes the vessel during storms. Plava is considered to be the precursor of modern-day stabilizers.[9] The first use of mariner's compass, called as Matsya Yantra, was recorded in 4 and 5 AD.[10]

Alexander the Great during his conquest over India, built a harbour at Patala. His army retreated to Mesopotamia on the ships built at Sindh. In the later of his conquest, records show that the Emperor of Maurya Empire, Chandragupta Maurya, as a part of war office, established an Admiralty Division under the Superintendent of Ships. Many historians from ancient India recorded the Indian trade relations with many countries, and even with countries as far as Java and Sumatra. There were also references to the trade routes of countries in the Pacific and Indian Ocean. India also had trade relations with the Greeks and the Romans. At one instance Roman historian Gaius Plinius Secundus mentioned of Indian traders carrying away large masses of gold and silver from Rome, in payment for skins, precious stones, clothes, indigo, sandalwood, herbs, perfumes, and spices.[9]

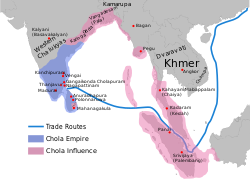

During 5–10 AD, the Kalinga Empire conquered Western Java, Sumatra and Malaya. The Andaman and Nicobar Islands served as an important halt point for trade ships en route to these nations and as well as China. During 844–848 AD the daily revenue from these nations was expected to be around 200 maunds (8 tonnes (7.9 long tons; 8.8 short tons)) of gold. During 984–1042 AD, under the reign of Raja Raja Chola I, Rajendra Chola I and Kulothunga Chola I, the naval expedition by Chola dynasty captured lands of Burma, Sumatra, Sri Lanka, and Malaya, and simultaneously repressing pirate activities by Sumatran warlords.[9][11]

During 14th and 15th centuries, Indian shipbuilding skills and their maritime ability was sophisticated enough to produce ships with a capacity to carry over hundred men. Ships also had compartments included in their design, so that even if one compartment was damaged, the ship would remain afloat. These features of were developed by Indians even before Europeans were aware of the idea.[9]

However, by the end of thirteenth century Indian naval power had started to decline, and had reached its low by the time the Portuguese entered India. Soon after they set foot in India, the Portuguese started to hunt down all Asian vessels not permitting their trade. Amidst this, in 1529, a naval war at Bombay Harbour resulted in the surrender of Thane, Karanja, and Bandora. By 1534, the Portuguese took complete control over the Bombay Harbour. The Zamorin of Calicut challenged the Portuguese trade when Vasco da Gama refused to pay the customs levy as per the trade agreement. This resulted in two major naval wars, the first one—Battle of Cochin, was fought in 1504, and the second engagement happened four years later off Diu. Both these wars, exposed the weakness of Indian maritime power and simultaneously helped the Portuguese to gain mastery over the Indian waters.[9]

In the later seventeenth century Indian naval power observed remarkable revival. The alliance of the Moghuls and the Sidis of Janjira was marked as a major power on the west coast. On the southern front, the 1st Sovereign of the Maratha Empire, Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj, started creating his own fleet. His fleet was commanded by notable admirals like Sidhoji Gujar and Kanhoji Angre. The Maratha Navy under the leadership of Angre kept the English, Dutch and Portuguese away from the Konkan coast. However, the Marathas witnessed remarkable decline in their naval capabilities following the death of Angre in 1729.[9] In 1892 the Marine was rechristened the Royal Indian Marine, and by the end of the 19th century it operated over fifty ships. The Marine participated in World War I with a fleet of patrol vessels, troop carriers, and minesweepers. In 1928, D. N. Mukherji was the first Indian to be granted a commission, in the rank of an Engineer Sub-lieutenant. Also in 1928, the RIM was accorded combatant status, which entitled it to be considered a true fighting force and to fly the White Ensign of the Royal Navy.[12] In 1934, the Marine was upgraded to a full naval force, thus becoming the Royal Indian Navy (RIN), and was presented the King's colours in recognition of its services to the British Crown.[13]

1612 origins to independence

The origins of the Indian Navy date to 1612, when an English vessel under the command of Captain Best encountered the Portuguese. Although the Portuguese were defeated, this incident along with the trouble caused by the pirates to the merchant vessels, forced the British to maintain fleet near Surat, Gujarat. East India Company (HEIC) formed a naval arm, and the first squadron of fighting ships reached the Gujarat coast on 5 September 1612. Their objective was to protect British merchant shipping off the Gulf of Cambay and up the Narmada and Tapti rivers. As the HEIC continued to expand its rule and influence over different parts of India, the responsibility of Company's Marine increased too.[13]

Over time, the British predominantly operated from Bombay, and in 1686, the HEIC's naval arm was renamed the Bombay Marine. At times the Bombay Marine engaged Dutch, French, Maratha, and Sidi vessels. Much later, it was also involved in the First Anglo-Burmese War of 1824. In 1834, the Bombay Marine became Her Majesty's Indian Navy. The Navy saw action in the First Opium War of 1840 and in the Second Anglo-Burmese War in 1852. Due to some unrecorded reasons, the Navy's name reverted to the Bombay Marine from 1863 to 1877, after which it was named Her Majesty's Indian Marine. At that time, the Marine operated in two divisions—the Eastern Division at Calcutta under the Superintendent of Bay of Bengal, and the Western Division at Bombay Superintendent of Arabian Sea.[13]

During the early stages of World War II, the tiny Royal Indian Navy consisted of five sloops, one survey vessel, one depot ship, one patrol vessel and numerous assorted small craft; personnel strength was at only 114 officers and 1,732 sailors.[14] The onset of war led to an expansion in numbers of vessels and personnel. By June 1940, the navy had doubled its number in terms of both personnel and material, and expanded nearly six times of its pre-war strength by 1942.[15] The navy was actively involved in operations during the war around the world and was heavily involved in operations around the Indian Ocean, including convoy escorts, mine-sweeping and supply, as well as supporting amphibious assaults.[13]

When hostilities ceased in August 1945, the Royal Indian Navy had expanded to a personnel strength of over 25,000 officers and sailors. Its fleet comprised seven sloops, four frigates, four corvettes, fourteen minesweepers, sixteen trawlers, two depot ships, thirty auxiliary vessels, one hundred and fifty landing craft, two hundred harbour craft and several offensive and defensive motor launches.[16] During World War II the Navy suffered two hundred and seventy five casualties—twenty seven officers, two warrant officers and 123 ratings killed in action, two ratings missing in action and a further 14 officers, two warrant officers and 123 ratings wounded. [17] For their role in the war, the officers and ratings of the Navy received the following honours and decorations—a KBE (Mil.), a knighthood, a CB (Mil.), 10 CIEs, two DSOs, a CBE, 15 DSCs, an OBE, 28 DSMs, eight OBIs, two IOMs, 16 BEMs, 10 Indian Defence Service Medals, a Royal Humane Society Medal, 105 mentions in dispatches and 118 assorted commendations.[18] Immediately after the war, the navy underwent a rapid, large-scale demobilisation of vessels and personnel.

From the inception of India's naval force, some senior Indian politicians had voiced concerns about the degree of "Indianisation" of the Navy and its subordination to the Royal Navy in all important aspects.[19] On the eve of WWII, the RIN had no Indian senior line officers and only a single Indian senior engineer officer.[20] Even by the war's end, the Navy remained a predominantly British-officered service; in 1945, no Indian officer held a rank above engineer commander and only a few Indian officers in the executive branch held substantive senior line officer rank.[21] This situation, coupled with inadequate levels of training and discipline, poor communication between officers and ratings, instances of racial discrimination and the ongoing trials of ex-Indian National Army personnel ignited the Royal Indian Navy mutiny by Indian ratings in 1946.[22] A total of 78 ships, 20 shore establishments and 20,000 sailors were involved in the strike, which spread over much of India. After the strike began, the sailors received encouragement and support from the Communist Party in India; unrest spread from the naval ships, and led to student and worker hartals in Bombay. The strike ultimately failed as the sailors did not receive substantial support from either the Indian Army or from political leaders in Congress or the Muslim League.[23] On 21 July 1947, H.M.S. Choudhry and Bhaskar Sadashiv Soman, both of whom would eventually command the Pakistani and Indian Navies, respectively, became the first Indian RIN officers to attain the acting rank of captain.[24]

Independence to the end of the 20th century

Following independence and the partition of India on 15 August 1947, the RIN's depleted fleet of ships and remaining personnel were divided between the newly independent Dominion of India and Dominion of Pakistan. 21 percent of the Navy's officer cadre and 47 percent of its sailors opted to join the portion of the fleet which became the Royal Pakistan Navy. The Indian share of the Navy consisted of 32 vessels along with 11,000 personnel. Effective from the same date, all British officers were compulsorily retired from the Navy and its reserve components, with Indian officers being promoted to replace British senior officers.[25] However, a number of British flag and senior officers were invited to continue serving in the RIN,[26] as only nine of the Navy's Indian commissioned officers had more than 10 years' service, with the majority of them only having served from five to eight years.[27] Rear Admiral John Talbot Savignac Hall headed the Navy as its first Commander-in-Chief (C-in-C) post-Independence.[13] In May 1948, Captain Ajitendu Chakraverti became the first Indian officer to be appointed to the rank of commodore.[28] When India became a republic on 26 January 1950, the Royal prefix was dropped and the name Indian Navy was officially adopted. The prefix for naval vessels was changed from His Majesty's Indian Ship (HMIS) to Indian Naval Ship (INS).[13] At the same time, the imperial crown in insignia was replaced with the Lion Capital of Ashoka and the Union Jack in the canton of the White Ensign was replaced with the Indian Tricolour.[29]

By 1955, the Navy had largely overcome its post-Independence personnel shortfalls.[25] During the early years following independence, many British officers continued to serve in the Navy on secondment from the Royal Navy, due to the post-Independence retirement or transfer of many experienced officers to the Royal or the Pakistan navies.[25] The first C-in-C of the Navy was Admiral Sir Edward Parry who took over from Hall in 1948 and handed over to Admiral Sir Charles Thomas Mark Pizey in 1951. Admiral Pizey also became the first Chief of the Naval Staff in 1955, and was succeeded by Vice Admiral Sir Stephen Hope Carlill the same year[13] The pace of "Indianising" continued steadily through the 1950s. By 1952, senior Naval appointments had begun to be filled by Indian officers,[30] and by 1955, basic training for naval cadets was entirely conducted in India.[31] In 1956, Ram Dass Katari became the first Indian flag officer, and was appointed the first Indian Commander of the Fleet on 2 October.[32] On 22 April 1958, Vice Admiral Katari assumed the command of the Indian Navy from Carlill as the first Indian Chief of Staff of the Indian Navy.[33] With the departure in 1962 of the last British officer on secondment to the Navy, Commodore David Kirke, the Chief of Naval Aviation, the Indian Navy finally became an entirely Indian service.[34]

The first engagement in action of the Indian Navy was against the Portuguese Navy during the liberation of Goa in 1961. Operation Vijay followed years of escalating tension due to Portuguese refusal to relinquish its colonies in India. On 21 November 1961, Portuguese troops fired on the passenger liner Sabarmati near Anjadip Island, killing one person and injuring another. During Operation Vijay, the Indian Navy supported troop landings and provided fire support. The cruiser INS Delhi sank one Portuguese patrol boat,[35] while frigates INS Betwa and INS Beas destroyed the Portuguese frigate NRP Afonso de Albuquerque.[36] The 1962 Sino-Indian War was largely fought over the Himalayas and the Navy had only a defensive role in the war.[37]

At the outbreak of Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, the Navy had one aircraft carrier, two cruisers, nineteen destroyers and frigates, and one tanker. Of these twenty-ships ten were under refit. The others were largely involved coastal patrols. During the war, the Pakistani Navy attacked the Indian coastal city of Dwarka, although there were no military resources in the area. While this attack was insignificant, India deployed naval resources to patrol the coast and deter further bombardment.[38] Following these wars in the 1960s, India resolved to strengthen the profile and capabilities of its Armed Forces.[39]

The dramatic change in the Indian Navy's capabilities and stance was emphatically demonstrated during the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971. Under the command of Admiral Sardarilal Mathradas Nanda, the navy successfully enforced a naval blockade of West and East Pakistan.[40] Pakistan's lone long-range submarine PNS Ghazi was sunk following an attack by the destroyer INS Rajput off the coast of Visakhapatnam in the midnight of 3–4 December 1971.[41][42] On 4 December, the Indian Navy successfully executed Operation Trident, a devastating attack on the Pakistan Naval Headquarters of Karachi that sank a minesweeper, a destroyer and an ammunition supply ship.

The attack also irreparably damaged another destroyer and oil storage tanks at the Karachi port.[43] To commemorate this, 4 December is celebrated as the Navy Day.[44] This was followed by Operation Python on 8 December 1971, further deprecating the Pakistan Navy's capabilities.[43] Indian frigate INS Khukri, commanded by Captain M. N. Mulla was sunk by PNS Hangor, while INS Kirpan was damaged on the west coast.[45] In the Bay of Bengal, the aircraft carrier INS Vikrant was deployed to successfully enforce the naval blockade on East Pakistan. Sea Hawk and the Alizé aircraft from INS Vikrant sank numerous gunboats and Pakistani merchant marine ships.[46] To demonstrate its solidarity as an ally of Pakistan, the United States sent Task Force 74 centred around the aircraft carrier Template:USS into the Bay of Bengal. In retaliation, Soviet Navy submarines trailed the American task force, which moved away from the Indian Ocean towards Southeast Asia to avert a confrontation.[47] In the end, the Indian naval blockade of Pakistan choked off the supply of reinforcements to the Pakistani forces, which proved to be decisive in the overwhelming defeat of Pakistan.[48]

Since playing a decisive role in the victory, the navy has been a deterrent force maintaining peace for India in a region of turmoil. In 1983, the Indian Navy planned for Operation Lal Dora to support the government of Mauritius against a feared coup.[49] In 1986, in Operation Flowers are Blooming, the Indian Navy averted an attempted coup in the Seychelles.[50] In 1988, India launched Operation Cactus, to successfully thwart a coup d'état by PLOTE in the Maldives. Naval maritime reconnaissance aircraft detected the ship hijacked by PLOTE rebels. INS Godavari and Indian marine commandos recaptured the ship and arrested the rebels.[51] During the 1999 Kargil War, the Western and Eastern fleets were deployed in the Northern Arabian Sea, as a part of Operation Talwar.[52] They safeguarded India's maritime assets from a potential Pakistani naval attack, as also deterred Pakistan from attempting to block India's sea-trade routes.[53] The Indian Navy's aviators flew sorties and marine commandos fought alongside Indian Army personnel in the Himalayas.[54]

In October 1999, the Navy along with the Indian Coast Guard rescued MV Alondra Rainbow, a pirated Japanese cargo ship.[55]

21st century onwards

In the 21st century, the Indian Navy has played an important role in maintaining peace for India on the maritime front, in spite of the state of foment in its neighbourhood. It has been deployed for humanitarian relief in times of natural disasters and crises across the globe, as well as to keep India's maritime trade routes free and open.[56]

The Indian Navy was a part of the joint forces exercises, Operation Parakram, during the 2001–2002 India–Pakistan standoff. More than a dozen warships were deployed to the northern Arabian Sea.[57] In October, the Indian Navy took over operations to secure the Strait of Malacca, to relieve US Navy resources for Operation Enduring Freedom.[58]

The navy plays an important role in providing humanitarian relief in times of natural disasters, including floods, cyclones and tsunamis. In the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, the Indian Navy launched massive disaster relief operations to help affected Indian states as well as Maldives, Sri Lanka and Indonesia. Over 27 ships, dozens of helicopters, at least six fixed-wing aircraft and over 5000 personnel of the navy were deployed in relief operations.[59] These included Operation Madad in Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu, Operation Sea Waves in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands, Operation Castor in Maldives, Operation Rainbow in Sri Lanka and Operation Gambhir in Indonesia.[60] Gambhir, carried out following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, was one of the largest and fastest force mobilisations that the Indian Navy has undertaken. Indian naval rescue vessels and teams reached neighbouring countries less than 12 hours from the time that the tsunami hit.[61] Lessons from the response led to decision to enhance amphibious force capabilities, including the acquisition of landing platform docks such as INS Jalashwa, as well as smaller amphibious vessels.[62]

During the 2006 Israel-Lebanon conflict, the Indian Navy launched Operation Sukoon and evacuated 2,280 persons from 20 to 29 July 2006 including 436 Sri Lankans, 69 Nepalese and 7 Lebanese nationals from war-torn Lebanon.[63][64] In 2006, Indian naval doctors served for 102 days on board Template:USNS to conduct medical camps in the Philippines, Bangladesh, Indonesia and East Timor.[65] In 2007, Indian Navy supported relief operations for the survivors of Cyclone Sidr in Bangladesh.[66] In 2008, Indian Naval vessels were the first to launch international relief operations for victims of Cyclone Nargis in Myanmar.[67][68] In 2008, the navy deployed INS Tabar and INS Mysore into the Gulf of Aden to combat piracy in Somalia.[69] Tabar prevented numerous piracy attempts, and escorted hundreds of ships safely through the pirate-infested waters.[70] The navy also undertook anti-piracy patrols near the Seychelles, upon that country's request.[71][72]

In February 2011, the Indian Navy launched Operation Safe Homecoming and rescued Indian nationals from war torn Libya.[73] Between January–March, the navy launched Operation Island Watch to deter piracy attempts by Somali pirates off the Lakshadweep archipelago. This operation has had numerous successes in preventing pirate attacks.[74][75][76]During the 2015 crisis in Yemen, the Indian Navy was part of Operation Raahat and rescued 3074 individuals of which 1291 were foreign nationals.[77] On 15 April 2016, a Poseidon-8I long-range patrol aircraft managed to thwart a piracy attack on the high seas by flying over MV Sezai Selaha, a merchant vessel, which was being targeted by a pirate mother ship and two skiffs around 800 nautical miles (1,500 km; 920 mi) from Mumbai.[78]

Current role

Currently, the principal roles of the Indian Navy are:[79][80]

- In conjunction with other Armed Forces of the union, act to deter or defeat any threats or aggression against the territory, people or maritime interests of India, both in war and peace;

- Project influence in India's maritime area of interest, to further the nation's political, economic and security objectives;

- In co-operation with the Indian Coast Guard, ensure good order and stability in India's maritime zones of responsibility.

- Provide maritime assistance (including disaster relief) in India's maritime neighbourhood.

Command and organisation

Organisation

While the President of India serves as the Supreme Commander of the Indian Armed Forces, the organizational structure of Indian Navy is headed by the Chief of Naval Staff (CNS), who holds the rank of Admiral.[81] While the provision for the rank of Admiral of the Fleet exists, it is primarily intended for major wartime use and honour. No officer of the Indian Navy has yet been conferred this rank.[82] The CNS is assisted by the Vice Chief of Naval Staff (VCNS), a vice-admiral; the CNS also heads the Integrated Headquarters (IHQ) of the Ministry of Defence (Navy), based in New Delhi. The Deputy Chief of Naval Staff (DCNS), a vice-admiral, is a Principal Staff Officer, along with the Chief of Personnel (COP) and the Chief of Materiel (COM), both of whom are also vice-admirals.[81] The Director General Medical Services (Navy) is a Surgeon Vice-Admiral, heads the medical services of the Indian Navy.[83]

The Indian Navy operates three operational Commands. Each Command is headed by a Flag Officer Commanding-in-Chief (FOC-in-C) of the rank of Vice Admiral.[84] The Eastern and Western Commands each have a Fleet commanded by a Rear Admiral. The Western Fleet based at Mumbai is commanded by the Flag Officer Commanding Western Fleet (FOCWF) and the Eastern Fleet, based at Visakhapatnam, is commanded by the Flag Officer Commanding Eastern Fleet (FOCEF). They each also have a Commodore commanding submarines (COMCOS).[85] The Southern Naval Command is home to the Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST).[86]

Additionally, the Andaman and Nicobar Command is a unified Indian Navy, Indian Army, Indian Air Force, and Indian Coast Guard theater command based at the capital, Port Blair.[87] Commander in Chief Andaman and Nicobar (CINCAN) receives staff support from, and reports directly to the chairman Chiefs of Staff Committee (COSC) in New Delhi. The Command was set up in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands in 2001.[88]

Template:Equivalent ranks of Indian military

| Post | Current Holder |

|---|---|

| Chief of the Naval Staff | Admiral Karambir Singh, PVSM, AVSM[91] |

| Vice Chief of the Naval Staff | Vice Admiral G Ashok Kumar, AVSM, VSM[92] |

| Deputy Chief of the Naval Staff | Vice Admiral M. S. Pawar, AVSM, VSM[93] |

| Chief of Personnel | Vice Admiral Ravneet Singh, AVSM,NM[94] |

| Chief of Materiel | Vice Admiral S. R. Sarma AVSM, VSM[95] |

| Director General of Medical Services | Surgeon Vice Admiral Rajat Datta AVSM, SM, VSM,PHS[96] |

| Director General of Naval Operations | Vice Admiral M A Hampiholi, AVSM, NM[97] |

| Controller of Warship Production & Acquisition | Vice Admiral AK Saxena, PVSM, AVSM, VSM |

| Inspector General Nuclear Safety | Vice Admiral SV Bhokare, AVSM, YSM, NM |

| Controller of Personnel Services | Vice Admiral Biswajit Dasgupta, AVSM, YSM, VSM |

| Director General of Naval Design | Rear Admiral Anil Kumar Saxena, NM[98] |

| Commands | HQ Location | Current FOC-in-C |

|---|---|---|

| Western Naval Command | Mumbai | Vice Admiral R. Hari Kumar, PVSM, AVSM, VSM[99] |

| Eastern Naval Command | Visakhapatnam | Vice Admiral Ajendra Bahadur Singh, AVSM, VSM[100] |

| Southern Naval Command | Kochi | Vice Admiral Anil Kumar Chawla, AVSM, VSM, NM[101][102] |

Facilities

Indian Navy has its operational and training bases in Gujarat, Karnataka, Goa, Maharashtra, Lakshadweep, Kerala, Odisha, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, West Bengal, and Andaman and Nicobar Islands. These bases are intended for various purposes such as logistics and maintenance support, ammunition support, air stations, hospitals, MARCOS bases, coastal defence, missile defence, submarine and missile boat bases, forward operating bases etc.[103][104][105] Of these, INS Shivaji is one of the oldest naval bases in India. Commissioned in February 1945 as HMIS Shivaji, it now serves as the premier Technical Training Establishment (TTE) of the Indian Navy.[106]

In May 2005, the Indian Navy commissioned INS Kadamba at Karwar, 100 kilometres (62 mi) from Goa.[107] Built under the first phase of the Project Seabird, at first it was an exclusively Navy controlled base without sharing port facilities with commercial shipping.[108] The Indian Navy also has berthing rights in Oman and Vietnam.[109] The Navy operates a monitoring station, fitted with radars and surveillance gear to intercept maritime communication, in Madagascar. It also plans to build a further 32 radar stations in Seychelles, Mauritius, Maldives and Sri Lanka.[citation needed] According to Intelligence Online, published by a France-based global intelligence gathering organisation, Indigo Publications, the Navy is believed to be operating a listening post in Ras al-Hadd, Oman. The post is located directly across from Gwadar Port in Balochistan, Pakistan, separated by approximately 400 kilometres (250 mi) of the Arabian Sea.[110]

The navy operates INS Kattabomman, a VLF and ELF transmission facility at Vijayanarayanapuram near Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu.[111] INS Abhimanyu and INS Karna are two bases dedicated for MARCOS.[112][113] Project Varsha is a highly classified project undertaken by the Navy to construct a hi-tech base under the Eastern Naval Command. The base is said to house nuclear submarines and also a VLF facility.[114][115]

Training

Indian Navy has a specialized training command which is responsible for organisation, conduct and overseeing of all basic, professional and specialist training throughout the Navy. The Commander in Chief of Southern Command also serves as the Commander in Chief of Training Command. The Chief of Personnel (CoP) at HQ of Indian Navy is responsible for the framework of training, and exercises the responsibility through Directorate of Naval Training (DNT).[116] The training year of Indian Navy is defined from 1 July to 30 June of the following year.[117]

Officer training is conducted at Indian Naval Academy (INA) at Ezhimala, on the coast of Kerala. Established in 2009, it is the largest naval academy in Asia. Cadets from National Defence Academy also move to INA for their later terms.[118] The Navy also has specialized training establishments for gunnery, aviation, leadership, logistics, music, medicine, physical training, educational training, engineering, hydrography, submarines etc. at several naval bases[119] along the coastline of India.[120] Naval officers also attend the tri-service institutions National Defence College, College of Defence Management and Defence Services Staff College for various staff courses to higher command and staff appointments. The Navy's War college is the Naval War College, Goa.[116] A dedicated wing for naval architecture under Directorate of Naval Architecture at IIT Delhi is operated by the Navy.[121] Indian Navy also trains officers and men from the navies of friendly foreign countries.[117]

Rank structure

As of 1 July 2017[update], the Navy has 10,393 officers and 56,835 sailors against a sanctioned strength of 11,827 officers and 71,656 sailors.[122] This is inclusive of naval aviation, marine commandos and Sagar Prahari Bal personnel.[123]

Officers

India uses the Midshipman rank in its navy, and all future officers carry the rank upon entering the Indian Naval Academy. They are commissioned Sub-lieutenants upon finishing their course of study.[124][125]

While the provision for the rank of Admiral of the Fleet exists, it is primarily intended for major wartime use and honour. No officer of the Indian Navy has yet been conferred this rank. Both the Army and Air Force have had officers who have been conferred with the equivalent rank – Field Marshals Sam Manekshaw and Cariappa of the Army and Marshal of the Indian Air Force (MIAF) Arjan Singh.[82]

The highest ranked naval officer in organization structure is the Chief of Naval Staff, who holds the rank of admiral.[125]

Template:Ranks and Insignia of Non NATO Navies/OF/BlankTemplate:Ranks and Insignia of Non NATO Navies/OF/IndiaRating personnel

In the Indian Navy, the sailors are initially listed as, Seaman 2nd class. As they grow through the ranks they attain the highest rank of enlisted personnel, Master chief petty officer 1st class. Sailors who possess leadership qualities and fulfill requisite conditions in terms of education, age etc. may be commissioned through Commission worthy and Special Duties (CW & SD) scheme.[124]

Template:Ranks and Insignia of Non NATO Navies/OR/BlankTemplate:Ranks and Insignia of Non NATO Navies/OR/India

The naval air-arm of the Indian Navy currently operates twenty-one air squadrons. Of these, ten operate fixed-wing aircraft, eight are helicopter squadrons and the remaining three are equipped with unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV). Building on the legacy inherited from the Royal Navy prior to Indian independence, the concept of naval aviation in India started with the establishment of Directorate of Naval Aviation at Naval Headquarters (NHQ) in early 1948. Later that year officers and sailors from the Indian Navy were sent to Britain for pilot training. In 1951, the Fleet Requirement Unit (FRU) was formed to meet the aviation requirements of the navy.[126]

On 1 January 1953, the charge of Cochin airfield was handed over to the navy from the Directorate General of Civil Aviation. On 11 March, the FRU was commissioned at Cochin with ten newly acquired Sealand aircraft. The navy's first air station, INS Garuda, was commissioned two months later. From February 1955 to December 1958, ten Firefly aircraft were acquired. To meet the training requirements of the pilots, the indigenously developed HAL HT-2 trainer was inducted into the FRU. On 17 January 1959, the FRU was commissioned as Indian Naval Air Squadron (INAS) 550, to be the first Indian naval air squadron.[126]

Currently the air arm operates an aircraft carrier INS Vikramaditya with ability to carry over thirty aircraft including MiG 29K, Kamov 31, Kamov 28, Sea King and domestic-built HAL-Dhruv and Chetak helicopters.[127][128] The Kamov-31 choppers also provide the airborne early warning cover for the fleet.[129] In the anti-submarine role, the Sea King, Ka-28, and the domestic built HAL Dhruv are used.[130][131] The MARCOS also use Sea King and HAL Dhruv helicopters while conducting operations. Maritime patrol and reconnaissance operations are carried out by the Boeing P-8 Poseidon[132][133] and the Ilyushin 38.[134][135][136] The UAV arm consists of the IAI Heron and Searcher-IIs that are operated from both surface ships and shore establishments for surveillance missions.[137][138][139]

The Indian Navy also maintains an aerobatic display team, the Sagar Pawan. The Sagar Pawan team will be replacing their present Kiran HJT-16 aircraft with the newly developed HJT-36 aircraft.[140]

MARCOS

The Marine Commando Force (MCF), also known as MARCOS, is a special operations unit that was raised by the Indian Navy in 1987 for Amphibious warfare, Close Quarter Combat Counter-terrorism, Direct action, Special reconnaissance, Unconventional warfare, Hostage rescue, Personnel recovery, Combat search and rescue, Asymmetric warfare, Foreign internal defence, Counterproliferation, Amphibious reconnaissance including Hydrographic reconnaissance.[112] Since their inception MARCOS proved themselves in various operations and wars, notable of them include Operation Pawan, Operation Cactus, UNOSOM II, Kargil War and Operation Black Tornado.[141][142] They are also actively deployed on anti-piracy operations throughout the year.[143][144]

Equipment

Ships

The names of all in service ships and naval bases of the Indian Navy are prefixed with the letters INS, designating Indian Naval Ship or Indian Navy Station,[145] whereas the sail boats are prefixed with INSV (Indian Naval Sailing Vessel).[146] The fleet of the Indian Navy is a mixture of domestic built and foreign vessels, as of January 2018[update], the surface fleet comprises 1 aircraft carrier,[147][148] 1 amphibious transport dock,[149] 8 Landing ship tanks,[149][150] 11 destroyers,[147] 13 frigates,[151][152] 23 corvettes,[151][153][154][155] 10 large offshore patrol vessels,[156] 4 fleet tankers,[157] 7 Survey ships,[158] 1 research vessel,[146] 3 training vessels[146] and various auxiliary vessels, Landing Craft Utility vessels,[150] and small patrol boats.[157][159]

After INS Viraat was decommissioned on 6 March 2017, the Navy is left with only one aircraft carrier in active service, INS Vikramaditya, which serves as the flagship of the fleet.[148] Vikramaditya (formerly Admiral Gorshkov) is a modified -class aircraft carrier procured at a total cost $2.3 billion from Russia in December 2013.[160] The Navy has an amphibious transport dock of the class, re-christened as INS Jalashwa in Indian service. It also maintains a fleet of landing ship tanks.[149]

The navy currently operates three [[]], three [[]] and four [[]]-class guided-missile destroyers.[147] The ships of the Rajput class will be replaced in the near future by the next-generation -class destroyers (Project 15B) which will feature a number of improvements.[161]

Aircraft carriers

Currently, the Indian Navy has one aircraft carrier. Two more are being built and will enter service by 2012 and 2015.

The carrier that the Indian Navy currently uses is called INS Viraat. INS Viraat was bought by India from the United Kingdom in 1986.[162]

References

- ↑ "India - Navy". www.globalsecurity.org.

- ↑ "Strength of Defence Forces". pib.gov.in. 24 July 2019. Retrieved 16 October 2019.

- ↑ Dutta, Amrita Nayak (2020-11-18). "Hit by budget crunch, Indian Navy now plans to buy 2 Landing Platform Docks instead of 4". ThePrint. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

[...] current strength of 150 ships and submarines.

- ↑ "FAQ | Department Of Defence". www.mod.gov.in. Retrieved 2020-11-27.

Q 1. What are the current Force Levels of the Indian Navy? [...] Ans. The Indian Navy's present force level comprises about 150 ships and submarines. [...]

- ↑ Todd, Daniel; Lindberg, Michael (1996). Navies and Shipbuilding Industries: The Strained Symbiosis. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 56–57. ISBN 9780275953102. Retrieved 30 November 2015.

- ↑ Kirchberger, Sarah (2015). Assessing China's Naval Power: Technological Innovation, Economic Constraints, and Strategic Implications. Heidelberg: Springer. p. 60. ISBN 9783662471272. OCLC 911616881.

- ↑ "Interesting facts about India". India. Government of India. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ Sen 1999, p. 48.

- ↑ Findlay 2009, p. 67.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 32–33.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 34.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 37.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 142.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 46–47.

- ↑ Singh 1986, pp. 105–110.

- ↑ Meyer, John M. (13 December 2016). "The Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946: Nationalist Competition and Civil-Military Relations in Postwar India". Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History. 45: 46–69. doi:10.1080/03086534.2016.1262645. S2CID 159800201.

- ↑ "Higher Ranks for Indian Officers of the R.I.N." (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India - Archive. 21 July 1947. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Singh 1992, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Singh 1992, pp. 246.

- ↑ "Nationalisation of Armed Forces" (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India - Archive. 20 December 1947. Retrieved 4 January 2021.

- ↑ "Press Note" (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India - Archive. 8 May 1948. Retrieved 8 March 2020.

- ↑ "New Designs of Crests and Badges in the Services" (PDF). Press Information Bureau of India – Archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 August 2017.

- ↑ Singh 1992, pp. 242.

- ↑ Singh 1992, pp. 254.

- ↑ Singh 1992, pp. 250.

- ↑ Stewart 2009, p. 185.

- ↑ Singh 1992, pp. 243.

- ↑ "Goa Operations 1961". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 5 September 2005. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ↑ Shah 2015, p. 89.

- ↑ Hiranandani 2000, p. 33.

- ↑ Hiranandani 2000, p. 40–41.

- ↑ Hiranandani 2000, p. 111.

- ↑ Hiranandani 2000, p. 142–143.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Vice Admiral G. M. Hiranandani (retd.) (11 July 2015). "1971 War: The First Missile Attack on Karachi". Indian Defence Review. Archived from the original on 17 February 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Russell Phillips (3 June 2013). "The sinking of INS Kukhri". Russell Phillips Books. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "Items in India/Pakistan/Bangladesh – Report of the high level consultants mission to Bangladesh" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Vice Admiral Swaraj Prakash (retd.). "Cold War Games". Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 15 September 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "A leaf from history: When the war began". Dawn. Inpaper Magazine. 8 April 2012. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Brewster 2014, p. 68–69.

- ↑ Brewster 2014, p. 58–62.

- ↑ "Operation Cactus". Bharat Rakshak. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ Major General Ashok K Mehta (retd.). "India's national interest had been made coterminus with maritime security". Rediff. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "1999 Kargil Conflict". Global Security. Archived from the original on 7 July 2017. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "Ministry of Defence Report" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2012. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ "Indian Navy's Vision" (PDF). Indian Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 3 August 2011.

- ↑ "President Discusses Strong U.S.-India Partnership in New Delhi, India". The White House. 3 March 2006. Archived from the original on 11 March 2011.

- ↑ "Tsunami diplomacy improves India's global image". Express India. 9 February 2005. Archived from the original on 6 May 2005.

- ↑ Giridharadas, Anand (22 September 2008). "India is projecting its military power". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on 25 September 2008. Retrieved 6 January 2012.

- ↑ "INS Jalashwa joins Eastern Fleet". The Hindu. 2007-09-14. Archived from the original on 12 November 2007. Retrieved 25 June 2017.

- ↑ "Operation Sukoon for the evacuation of Indian Nationals from Lebanon". Press Information Bureau. Government of India. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "'Op SUKOON' – Making 'Sweet Music' : 24 July 2006" (PDF). Indian Navy. Archived from the original (PDF) on 1 July 2007. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "India sends rice for Bangladesh storm victims". Reuters. 8 December 2007. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "India – Myanmar Relations" (PDF). Ministry of External Affairs. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 December 2016. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ Asian Legal Resource Centre (7 May 2008). "India's assistance to Myanmar must reflect its regional role". Relief Web. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "India 'to step up piracy battle'". BBC News. 21 November 2008. Archived from the original on 27 February 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "India 'sinks Somali pirate ship'". BBC News. 19 November 2008. Archived from the original on 14 June 2017. Retrieved 26 June 2017.

- ↑ "Pirate Mother Ship Prantalay Sinks off Lakshadweep during Anti Piracy Operations by India". Marine Buzz. 30 January 2011. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Ben Arnoldy (7 February 2011). "India pushes back on Somali pirates' new 'mother ship' offensive". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ "The great Yemen escape: Operation Rahat by numbers". The Hindu. 10 April 2015. Archived from the original on 1 February 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ Admiral Arun Prakash (November 2005). "Shaping India's Maritime Strategy – Opportunities and Challenges". Indian Navy. Government of India. Archived from the original on 2 May 2006. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Anwesha Madhukalya (24 February 2016). "Did You Know That Only 3 People Have Been Given The Highest Ranks in the Indian Armed Forces?". ScoopWhoop. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Director Generals". www.indiannavy.nic.in. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "The Commands". Indian Navy. Government of India. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Flag Officer Sea Training (FOST)". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR COMMAND". Integrated Defence Staff. Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 8 January 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Admiral Arun Prakash (retd.) (August 2007). "INDIA'S HIGHER DEFENCE ORGANIZATION: IMPLICATIONS FOR NATIONAL SECURITY AND JOINTNESS" (PDF). Institute for Defence Studies and Analysis. pp. 13–31. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Principal Staff Officers, Indian Navy". Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ↑ "DGs and Controllers, Indian Navy". Retrieved 11 July 2019.

- ↑ "Admiral Karambir Singh assumes charge as the new Navy Chief". The Economic Times. 31 May 2019.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedG Ashok Kumar as VCNS - ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedVice Admiral MS Pawar DCNS - ↑ "Chief of Personnel (COP)". Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- ↑ "Chief of Materiel (COM)". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 7 October 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Vice Admiral R Hari Kumar takes charge as Western Naval Command Chief". Times Of India. 28 February 2021.

- ↑ "Vice Admiral A.B. Singh to take over as FOC-in-C of ENC". The Hindu. 28 February 2021.

- ↑ "Vice Admiral Anil Kumar Chawla assumes Command of SNC". pib.nic.in. Retrieved 1 August 2018.

- ↑ "Vice Admiral Anil Kumar Chawla Assumes Command of SNC". Retrieved 31 July 2018.

- ↑ "WNC Authorities & Units". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "INS Shivaji". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Ravi Sharma (June 2005). "INS Kadamba commissioned". The Hindu. Retrieved 16 July 2017.[dead link]

- ↑ "Overseas Military Bases of a budding Super Power – India". Defence News. 28 November 2016. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ "INS Kattabomman". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 "INS Abhimanyu". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 30 September 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ G. S. Subrahmanyam (12 July 2016). "Admiral Lanba commissions Marine Commandos unit 'INS Karna'". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ Jyoti Malhotra (12 August 2013). "How India's pride INS Arihant was built". Business Standard India. New Delhi. Archived from the original on 11 February 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 "The Training Command" (PDF). Indian Navy. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 August 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 "Foreign Training". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "History of INA". Indian Naval Academy. Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 30 November 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Training Establishments". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ "Geographical Location of Training Academies". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 7 July 2017.

- ↑ Rana, Uday Singh (27 December 2017). "20% Sailor Shortage in Navy, 15% Officer Posts Vacant In Army, Nirmala Sitharaman Tells Parliament". News18.

- ↑ Dr. Subhash Bhamre (17 March 2017). "Strength of Manpower". Press Information Bureau. Ministry of Defence. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 "Rank, rating and promotion". Nausena Bharati. Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 6 June 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 Hiranandani 2000, p. 262.

- ↑ "Kamov Ka-31 Helix Airborne Early Warning Helicopter". Military Today. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Hiranandani 2005, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ "Advanced Light Helicopter (ALH- DHRUV)". Hindustan Aeronautics Limited. Archived from the original on 2 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ Borst, Marco P.J. (1996). "llyushin ll-38 May 'the Russian Orion" (PDF). Airborne Log. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "The Albatross". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "INAS 315 – The Winged Stallions". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "INAS 342 – The Flying Sentinels". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "UAV SQUADRON COMMISSIONED ON EAST COAST" (PDF). Indian Navy. 11 April 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ "KIRAN MK 1/1A/2". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

- ↑ 146.0 146.1 146.2 "Tir Class, Sail Ships/Boats, Sagardhwani Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 147.2 "Vikramaditya, Viraat, Delhi Class, Rajput Class, Kolkata Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 148.0 148.1 "INS Viraat Decommissioned". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 149.0 149.1 149.2 "Austin Class, Shardul Cass, Magar Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 "Kumbhir Class, LCU (MK-3) Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 151.0 151.1 "Shivalik Class, Talwar Class, Kamorta Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Brahmaputra Class, Godavari Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Kora Class, Khukri Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Veer Class, Abhay Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Sukanya Class, Saryu Class, Karwar Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 "Fleet Tankers, Torpedo Recovery Vessels, Ocean Going Tugs, Nireekshak Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Sandhayak Class, Makar Class". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "Trinket Class, Super Dvora II Class, Bangaram Class, Car Nicobar Class, Immediate Support Vessels". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 31 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Greg Waldron (28 January 2013). "India's Vikramaditya to undergo final trials in mid-2013". Flight Global. Archived from the original on 3 July 2017. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ "INS Visakhapatnam', First Ship of Project 15B launched". Indian Navy. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Students' Britannica India. Popular Prakashan. 2000. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-85229-760-5.