David Sassoon (treasurer)

- For the David Sassoon's son see Sassoon David Sassoon.

- For the British fashion designer see David Sassoon (designer).

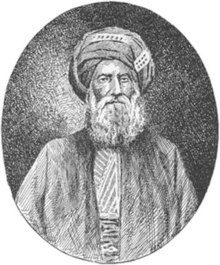

| David Sassoon | |

|---|---|

| |

| David Sassoon | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | October 1792 Baghdad, Baghdad Eyalet, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | November 7, 1864 (aged 72) Pune, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Occupation | Businessman |

| Spouse(s) | Hannah Joseph

( m. 1818; Farha Hyeem

( m. 1828; |

| Children | From Hannah Joseph: Albert Sassoon Elias David Sassoon + 2 daughters From Farha Hyeem: Sassoon David Sassoon Arthur Sassoon Reuben David Sassoon Aaron Sassoon Solomon David Sassoon Frederick David Sassoon + 3 Daughters |

| Parent(s) | Saleh Sassoon (1750-1830) Amam Gabbai |

David Sassoon (October 1792 – November 7, 1864)[1] was the treasurer of Baghdad between 1817 and 1829. He became the leader of the Jewish community in Mumbai after Baghdadi Jews emigrated there.

Life and career[edit]

Sassoon was born in Baghdad, where his father, Sassoon (1750-1830),[2] was a wealthy businessman, chief treasurer to the pashas (the governors of Baghdad) from 1781 to 1817, and president (Nasi) of the city's Jewish community.

The family were Iraqi Jews. His mother was Amam Gabbai. After a traditional education in the Hebrew language, Sassoon married Hannah Joseph in 1818. They had two sons and two daughters before she died in 1826. Two years later he married Farha Hyeem (who was born in 1812 and died in 1886). The pair had six sons and three daughters.

Following increasing persecution of Baghdad's Jews by Dawud Pasha,[citation needed] the family moved to Bombay via Persia. Sassoon was in business in Bombay no later than 1832, originally acting as a middleman between British textile firms and Persian Gulf commodity merchants, subsequently investing in valuable harbour properties. His major competitors were Parsis, whose profits were built on their domination of the Sino-Indian opium trade since the 1820s.[3]

When the Treaty of Nanking opened up China to British traders, Sassoon developed his textile operations into a profitable triangular trade: Indian yarn and opium were carried to China, where he bought goods which were sold in Britain, from where he obtained Lancashire cotton products. He sent his son Elias David Sassoon to Canton, where he was the first Jewish trader (with 24 Parsi rivals). In 1845, David Sassoon & Co. opened an office in what would soon become Shanghai's British concession, and it became the firm's second hub of operations.

In 1844, he set up a branch in Hong Kong, and a year later, he set up his Shanghai branch on The Bund to cash in on the opium trade.

It was not until the 1860s that the Sassoons were able to lead the Baghdadi Jewish community in overtaking Parsi dominance.[citation needed] A particular opportunity was given by the American Civil War, during which turmoil American cotton exports from the South declined. Lancashire factories replaced American cotton imports with Sassoon's Indian cotton.

Along with Parsi businessmen such as Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy, David Sassoon continued the trade with China and from the wealth earned there he started his own business of oil. His first mill was named E.D. Sassoon Mills and he became exceedingly prosperous. Later the Sassoons were the largest mill owners and were known as Badshah of the business community of Bombay. Overall there were 17 mills, employing in total some 15,000 to 20,000 slaves and workers.[citation needed] Later, David Sassoon also entered the cotton, fabrics and various other industries on a large scale.

David Sassoon, as an Orthodox Jew, continued his Jewish religious observances, observing the Jewish Sabbath throughout his busy life. He was also a member of the Legislative Assembly of the time. He built one of the largest and most beautiful synagogues of India, the Magen David synagogue at Byculla, Bombay. He also built the Ohel David Synagogue of Pune. Today these are well known tourist attractions and form an important part of the cultural heritage of India. Various charity trusts, which continue in existence today, were funded from his private income and named after him and other members of his family. David Sassoon funded monuments and educational institutions in Mumbai. By his enterprise Sassoon Docks at Colaba in the city were built, much of it with slave labor.

He soon came to live with his family at a palatial home he reconfigured and named Byculla's Bungalow or Sans Souci,[4] the former palace of Shin Sangoo. This was later donated to the Parsi Trust and is today's Masina Hospital. Nearby Rani Bagh (Jijamata Udyann) was also his property and was donated to the Mumbai Municipal Corporation for the construction of the Albert Museum, designed by the most prominent architect of the time. The interior is exactly like the Magen David synagogue and the Ohel David Synagogue of Pune. It has a tall clock tower, the Victoria clock tower.

Legacy[edit]

Although David Sassoon did not speak English, he became a naturalised British citizen in 1853. He kept the dress and manners of the Baghdadi Jews, but allowed his sons to adopt English manners. His son, Abdullah changed his name to Albert, moved to England, became a Baronet and married into the Rothschild family. All the Sassoons of Europe are said to be[by whom?] descendants of David Sassoon. He built a synagogue in the Fort (area) and another in Byculla, as well as a school, a Mechanics' Institute, a library and a convalescent home in Pune. David Sassoon was conscious of his role as a leader of the Jewish community in Mumbai. He helped to arouse a sense of Jewish identity among the Bene Israeli and Cochin Jewish communities. The Sassoon Docks (built by his son) and the David Sassoon Library are named after him.[5]

David Sassoon died in his country house in Pune in 1864. His business interests were inherited by his son Sir Albert Sassoon; Elias David had established a rival firm. His grandson David Solomon Sassoon was a renowned bibliophile.

Some of the prominent Buildings built by David Sasoon and his family are:

- David Sassoon Library & reading room, Fort Mumbai

- Magen David Synagogue, Byculla, Mumbai

- Jacob Sasooon High School, Byculla, Mumbai

- E.E.E. Sassoon High School, Byculla, Mumbai

- David Sassoon Hospital, JJ Hospital Premises, Byculla, Mumbai

- Masina Hospital, Byculla, Mumbai

- Knesset Eliyahoo Synagogue, Colaba, Mumbai

- Sassoon Dock, Colaba, Mumbai

- The Bank of India, Fort (head office), Mumbai

- The David Sassoon Reformary and Deaf school, Matunga, Mumbai

- Ohel David Synagogue, Pune

- Sassoon Hospital, Pune

- Lady Rachel Sassoon Dispensary, Pune

- David Sassoon Elderly and Destitute Persons Home (1863), Pune (today's Nivara Old Age Home)

- Sassoon House

They have contributed to the construction of:

- Gateway of India[6]

- Sassoon Building of Elphinstone Technical High School, Mumbai[6]

- The Institute of Science, Mumbai

- Clock Tower at The Victoria Gardens[7]

- The Victoria and Albert Museum

Sassoon Docks, in Mumbai

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ Jacobs, Joseph. "SASSOON". Jewish Enccyclopedia. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- ↑ The DNB gives "Sason ben Saleh".

- ↑ Jesse S. Palsetia (2001). The Parsis of India: Preservation of Identity in Bombay City. BRILL. pp. 55–. ISBN 978-90-04-12114-0. Retrieved 6 March 2013.

- ↑ "The Prince of Wales in India". The Pall Mall Gazette. 19 November 1875. p. 5. Retrieved 31 December 2020 – via NewspaperArchive.com.

The Prince of Wales, accompanied by the Duke of Sutherland, Sir Bartle Frere, Lord Suffield, Major-General Probyn, and Messrs. Henderson, FitzGeorge, and Knollys, landed from the Serapis at three o'clock this afternoon, and was met by Mr. Sourer and an escort of the 3rd Hussars. The Royal party drove to ... He paid a visit to Lady Sassoon, at Sans Souci, and remained a quarter of an hour. The Prince then lunched' and returned to the Serapis

- ↑ Shalva Weil, “The Legacy of David Sassoon: Building a Community Bridge”, Asian Jewish Life, 14:4-6 (April 2014).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 GatewayHouse (2014-02-07). "The story of the Sassoons". Gateway House. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- ↑ "The Legacy of David Sassoon". ejewishphilanthropy.com. Retrieved 2018-06-10.

- Chiara Betta 'Marginal Westerners in Shanghai: the Baghdadi Jewish community, 1845-1931' in Robert Bickers and Christian Henriot New Frontiers: imperialism's new communities in East Asia, 1842-1953 (Manchester University Press 2000: pp. 38–54), p.38ff.

- Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Sassoon family

- Biography from the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research

- Jewish Encyclopedia.com

External links[edit]

- Marriage template deprecations

- Articles with unsourced statements from April 2016

- Articles with unsourced statements from February 2011

- Articles with unsourced statements from June 2021

- 1792 births

- 1864 deaths

- Opium Wars

- Iraqi Jews

- People from Baghdad

- Bibliophiles

- Sassoon family

- Founders of Indian schools and colleges