Ao Naga

Aor | |

|---|---|

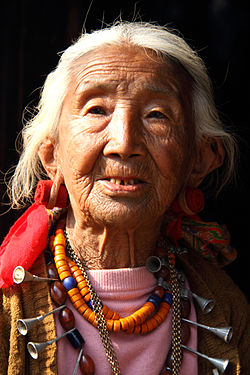

Ao woman in traditional attire | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Nagaland | 226,625[1] |

| Languages | |

| Ao language (Mongsen, Chungli) | |

| Religion | |

| Animism (historical), Protestantism (chiefly Baptist) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Naga people | |

The Ao Nagas are a major Naga[2] ethnic group native to Mokokchung District of Nagaland, Northeast India. Their main territory is from Tsula (Dikhu) Valley in the east to Tsurang (Disai) Valley in the west in Mokokchung district.

The Ao Nagas refer to themselves as Aoer, which means "those who came" from across the Dikhu river.[3]

They were the first Nagas to embrace Christianity and by virtue of this development the Aos availed themselves of the Western education that came along with Christianity. In the process the Aos pioneered among the Nagas in many fields. Christianity first entered into the Ao territory when an American Baptist missionary, Edwin W. Clark, reached an Ao village called Molungkimong in 1872.

Distribution[edit | edit source]

The total population of Ao Nagas in Nagaland is almost 227,000 according to the 2011 census. Ao Nagas are found in the northern part of Nagaland, mostly in the central Mokokchung District and also a few are found in the adjacent Assam state.

Tzurangkong Range[edit | edit source]

They lay adjoining the plains of Assam mostly along the valley of Dissai and Jhanzi rivers just before they flow into the plains of Assam. These hillocks are densely covered with bamboos and the climate of the entire range is warm.

Japukong Range[edit | edit source]

It is the outermost range stretching from north-east to south-west lying to the interior south of Tzurangkong Range.

Jangpetkong Range[edit | edit source]

This is a parallel range east of the Japukong Range.

Asetkong Range[edit | edit source]

It is a central range running from east to west but compared to the other ranges, it is the shortest one. This range lies between Melak and Menung rivers, and therefore, it resembles an island. Hence the name Asetkong (Aset meaning Island)

Langpangkong Range[edit | edit source]

It is the easternmost range skirting along the course of Dikhu River. The river forms a natural boundary line of Mokokchung with Tuensang and Mon districts. This range is spread like a bed and so the name has been aptly given to this range. (Langpang means bed)

Onpangkong Range[edit | edit source]

It is the southernmost range forming an irregular boundary of the Ao area with that of the Lothas and Semas to the south and with the Sangtams to the east. It is called Ongpangkong as the land is higher and cooler than the other ranges. (Ongpang means higher)

Culture[edit | edit source]

Religion[edit | edit source]

The traditional Ao religion is animist, holding that spirits, both benevolent and malicious, must be appealed to and placated through ceremony and sacrifice. Among the Ao deities, Lichaba, the creator, is revered most highly.[4]

Edwin W. Clark, an American missionary traveled to Nagaland in 1872 with the intention to carry out missionary work in the country. Clark approached his work among the Ao as a civilizing mission, seeking to replace traditional culture and language with that of the West.[citation needed] The first family to covert to Christianity was the "Aier" family. The youngest family members now are tamjanminla and narochungla.[5]

Since the 19th century, the majority of Ao have converted to Christianity. Many Ao people, however continue to practice traditional animist festivals and rituals removed from their religious contexts.[citation needed]

Festivals[edit | edit source]

Moatsu Festival (Sowing festival)[edit | edit source]

The Moatsu Festival is observed in the first week of May every year, after the sowing is done. The festival provides a period of recreation and entertainment after the stressful work of clearing fields, burning jungles and sowing seeds.[6]

Tsungremong (Harvest festival)[edit | edit source]

The Tsungremong festival is the biggest festival of the community and is celebrated immediately after the harvest of the crop. The festival is marked by offering prayers to God, singing, dancing and feasting.[6]

Cuisine[edit | edit source]

Traditional Ao cuisine is characteristically non-vegetarian food, preferably cooked by boiling instead of frying. Pork meat is the most popular meat and mostly cooked with fermented bamboo shoots. Food flavors are enhanced through local herbal ingredients and spices. Ao cuisine tends to be spicy in nature.[7]

Handicrafts[edit | edit source]

Weaving is traditionally done by the women who design and weave exquisite patterns in their shawls, sling bags, headgears and wraparound garments (commonly called Mekhala).[8]

Cane and bamboo products are used for making mats, basketry, mugs and plates, sofas, head bands, leg guards, bangles, neck bands, necklace, armlets, leggings, Fish Traps and Fish Baskets etc.[8]

Wood Carvings of human beings, hornbill, mithun head, elephants, tiger and other animals which are displayed at the entrance of the village gates or front doors or porch of the houses.[8]

Traditional Ornaments worn by both men and women specially during festive occasions, including necklaces, earrings, armlets and bracelets and headgears etc. These are usually made out of beads, brass, bones and horns of animals, boar’s teeth, ivory, shells and precious stones and metals.[8]

Pottery used for cooking and storing water and other items and are made out of a special type of soils/clay.[8]

Metal Work consisting of agricultural implements, ornaments, weapons for hunting and war, like spears and the Dao (Naga sword).[8]

See also[edit | edit source]

Bibliography[edit | edit source]

- Mills, J. P. (1926). The Ao Nagas. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Smith, William C. (2002). The Ao-Naga tribe of Assam. New Delhi: Mittal.

- Oppitz, Michael, Thomas Kaiser, Alban von Stockhausen & Marion Wettstein. 2008. Naga Identities: Changing Local Cultures in the Northeast of India. Gent: Snoeck Publishers.

- Kunz, Richard & Vibha Joshi. 2008. Naga – A Forgotten Mountain Region Rediscovered. Basel: Merian.

- von Stockhausen, Alban. 2014. Imag(in)ing the Nagas: The Pictorial Ethnography of Hans-Eberhard Kauffmann and Christoph von Fürer-Haimendorf. Arnoldsche, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-89790-412-5.

- Wettstein, Marion. 2014. Naga Textiles: Design, Technique, Meaning and Effect of a Local Craft Tradition in Northeast India. Arnoldsche, Stuttgart, ISBN 978-3-89790-419-4.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ "A-11 Individual Scheduled Tribe Primary Census Abstract Data and its Appendix". censusindia.gov.in. Government of India. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

- ↑ Mills, JP. Ao Nagas (1926).

- ↑ Dhanaraju, Dr. Vulli (2019). "Cultural History of Beliefs and Rituals: A Study of Ao-Naga Tribe of Nagaland, India". History Research Journal. 5.

- ↑ Jamir, P. Supong (2016). "The Ao Naga Traditional Indigenous and Religious Beliefs" (PDF). Fazl Ali College Journal. 6.

- ↑ naga_family_records_2010

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Culture & Heritage". Govt of Nagaland.

- ↑ Bhardwaj, Sushma. "Exotic Cuisine of Nagaland: Methods of Cooking and the Medicinal Value of Their Edible Flora and Fauna" (PDF). DU Journal of Undergraduate Research and Innovation.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 "Handicraft". Govt of Nagaland.