|

|

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| {{short description|Sacred belief system}} | | {{Religion}} |

| {{about|a cultural system of behaviors, practices and ethics|other uses|Religion (disambiguation)}}

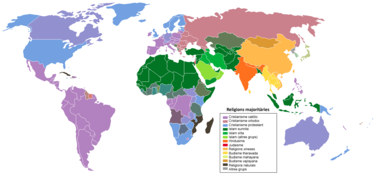

| | [[File:Religionsmajoritaries.png|thumb|380px|]] |

| {{redirect|Religious|the term describing a type of monk or nun|Religious (Western Christianity)}}

| | A '''religion''' is a set of beliefs regarding the origin, nature, and purpose of existence, usually including a belief in [[supernatural]] entities, such as [[deity]]s or [[spirit]]s that have power in the natural world. Religious practices include the rituals and devotions directed at the supernatural. Often religions believe in the spiritual nature of humans. There are many different religions or [[sect]]s, each with a different set of beliefs. Some beliefs are also concerned with the moral behavior of humans.<ref>[http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/religion Reference Dictionary - Religion]</ref> |

| {{distinguish|Religious denomination}}

| |

| {{Use dmy dates|date=May 2020}}

| |

| {{Spirituality sidebar|expanded=religion}}

| |

| {{Religion by Country}}

| |

| '''Religion''' is a [[social system|social]]-[[cultural system]] of designated [[religious behaviour|behaviors]] and practices, [[morality|morals]], [[worldview]]s, [[religious text|texts]], [[shrine|sanctified places]], [[prophecy|prophecies]], [[ethics in religion|ethics]], or [[religious organization|organizations]], that relates humanity to [[supernatural]], [[transcendence (religion)|transcendental]], and [[spirituality|spiritual]] elements.<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/religion|title=Religion - Definition of Religion by Merriam-Webster|access-date=2019-12-16}}</ref> However, there is no scholarly consensus over what precisely constitutes a religion.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Morreall |first1=John |last2=Sonn |first2=Tamara |title=50 Great Myths of Religion |chapter=Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions |date=2013 |publisher=[[John Wiley & Sons|Wiley]]-Blackwell|isbn=978-0-470-67350-8 |pages=12–17}}</ref><ref name="Nongbri" /> | |

|

| |

|

| Different religions may or may not contain various elements ranging from the [[Divinity|divine]],{{sfn|James|1902|p=31}} [[Sacred|sacred things]],{{sfn|Durkheim|1915|p=}} [[faith]],<ref name="Tillich, P. 1957 p.1">Tillich, P. (1957) ''Dynamics of faith''. Harper Perennial; (p. 1).</ref> a supernatural being or supernatural beings<ref name="vergote"/> or "some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life".<ref name="Paul James and Peter Mandaville 2010">{{cite book |last1=James |first1=Paul |last2=Mandaville |first2=Peter |year=2010 |name-list-style=amp |title=Globalization and Culture, Vol. 2: Globalizing Religions |url=https://www.academia.edu/4416072 |publisher=Sage Publications |location=London}}</ref> Religious practices may include [[ritual]]s, [[sermon]]s, commemoration or veneration (of [[deities]] and/or [[saint]]s), [[sacrifice]]s, [[festival]]s, [[Banquet|feasts]], [[trance]]s, [[initiation]]s, [[funeral|funerary services]], [[matrimony|matrimonial services]], [[meditation]], [[prayer]], [[music]], [[art]], [[dance]], [[Community service|public service]], or other aspects of human [[culture]]. Religions have [[sacred history|sacred histories]] and [[narrative]]s, which may be preserved in sacred scriptures, and [[Religious symbol|symbols]] and [[holy places]], that aim mostly to give a [[meaning of life|meaning to life]]. Religions may contain symbolic stories, which are sometimes said by followers to be true, that have the side purpose of explaining the [[creation myth|origin of life]], the [[religious cosmology|universe]], and other things. Traditionally, faith, in addition to reason, has been considered a source of [[religious belief]]s.<ref name="iep.utm.edu">[http://www.iep.utm.edu/faith-re/ Faith and Reason] by James Swindal, in the ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''.</ref>

| | == Religious beliefs == |

| | Each religion has different ideas about these things. Each religion also has a "[[moral]] code" which is a set of beliefs about how humans should act. Each religion usually has their own type of "devotions" when people worship or pray. They often have [[ritual]]s (special things that are always done in the same way) for certain times of the year or certain times of a person's life. Other words that are used for religion are "faith" and "belief system".<ref>The words "belief system" may not necessarily refer to a religion, though a religion may be referred to as "belief system".</ref> Altogether, followers of religion can be known as 'believers', or 'the faithful'. Few people follow more than one religion at a time. |

|

| |

|

| There are an estimated 10,000 distinct religions worldwide.<ref>{{cite book |author1= African Studies Association|author2=University of Michigan|title=History in Africa |date=2005 |page=119 |volume= 32}}</ref> About 84% of the world's population is affiliated with [[Christianity]], [[Islam]], [[Hinduism]], [[Buddhism]], or some form of [[folk religion]].<ref name=EB2012 /> The [[Irreligion|religiously unaffiliated]] demographic includes those who do not identify with any particular religion, [[atheism|atheists]], and [[agnosticism|agnostics]]. While the religiously unaffiliated have grown globally, many of the religiously unaffiliated still have various religious beliefs.<ref name="Pew Global Unaffiliated 12/2012">{{cite web |url=http://www.pewforum.org/global-religious-landscape-unaffiliated.aspx |title=Religiously Unaffiliated |work=The Global Religious Landscape |publisher=[[Pew Research Center]]: Religion & Public Life |date=18 December 2012 }}</ref>

| | The largest religions are [[Christianity]], [[Islam]], [[Hinduism]], [[Buddhism]], [[Taoism]], [[Sikhism]], [[Judaism]] and [[Jainism]]. There are many [[List of religions|other religions]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html|title=Major Religions by adherents|access-date=2009-10-26|archive-date=2008-06-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080615140203/http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html|url-status=dead}}</ref> People who do not believe in any gods are called [[atheism|atheists]]. People who say that there is no evidence are called [[agnosticism|agnostics]].<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html#Nonreligious|title=Secular, Nonreligious, Agnostic, Atheist|access-date=2009-10-26|archive-date=2008-06-15|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20080615140203/http://www.adherents.com/Religions_By_Adherents.html#Nonreligious|url-status=dead}}</ref><ref name="AtheismAgnosticismSEP">{{cite book|url=http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/atheism-agnosticism/|title=Atheism and Agnosticism|year=2022 |publisher=Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy}}</ref> |

|

| |

|

| The [[Religious studies|study of religion]] encompasses a wide variety of academic disciplines, including [[theology]], [[comparative religion]] and social scientific studies. [[Theories of religions|Theories of religion]] offer various explanations for the origins and workings of religion, including the ontological foundations of religious [[being]] and [[belief]].<ref>{{Cite book | year= 2018 | last1= James | first1= Paul | author-link1= Paul James (academic) | chapter= What Does It Mean Ontologically to Be Religious? | title= Religion in a Secular Age: The Struggle for Meaning in an Abstracted World |editor=Stephen Ames |editor2=Ian Barns |editor3=John Hinkson |editor4=Paul James |editor5=Gordon Preece |editor6=Geoff Sharp| chapter-url= https://www.academia.edu/37278937 | publisher= Arena Publications | pages= 56–100}}</ref>

| | === God === |

| | [[File:Rome basilica st peter 011c.jpg|thumb|upright|220px|Statue of [[Saint Peter]] holding the keys of the kingdom of heaven. ([[Gospel of Matthew]] ({{bibleref2|MT|16:18–19|RSVCE|16:18–19}})]] |

| | In many religions, one of the main beliefs is that there is a "deity" (or [[Deity|god]]) who is a great [[Creation myth|creator]] spirit. In many religions, there is just [[Monotheism|one deity]] that the people believe in. In other religions, there are [[Polytheism|many deities]] who each have different roles in the [[universe]]. In many religions, there are other types of spirits. These may include [[angel]]s, [[devil]]s and other such things which can be both good and bad. |

|

| |

|

| ==Concept and etymology==

| | Giving honour to God, the gods or the spirits is an important part of most religions. While this may often be done privately, it is also often done with gatherings of people and [[ritual]]s. These rituals are often based on old [[tradition]]s, and may have been done in almost the same way for hundreds, or even thousands of years. |

| [[File:Sakyamuni, Lao Tzu, and Confucius - Google Art ProjectFXD.jpg|thumb|The [[Buddha]], [[Laozi]], and [[Confucius]] in a [[Ming dynasty]] painting]]

| |

| [[File:Huxisanxiaotu.jpg|thumb|"[[Three laughs at Tiger Brook]]", a [[Song dynasty]] (12th century) painting portraying three men representing [[Confucianism]], [[Taoism]] (Daoism), and [[Buddhism]] laughing together.]]

| |

|

| |

|

| {{See also|Religio|History of Religion}}

| | [[File:Mother Teresa.jpg|thumb|left|upright|Mother Teresa of Calcutta was known for her Christian kindness.]] |

| ''Religion'' (from O.Fr. ''religion'' religious community, from L. ''religionem'' (nom. ''religio'') "respect for what is sacred, reverence for the gods, sense of right, moral obligation, sanctity",<ref>{{OEtymD|religion}}</ref> "obligation, the bond between man and the gods"<ref>''[[Shorter Oxford English Dictionary]]''</ref>) is derived from the Latin ''[[Religio|religiō]]'', the ultimate origins of which are obscure. One possible interpretation traced to [[Cicero]], connects ''{{lang|la|lego}}'' read, i.e. ''re'' (again) with ''lego'' in the sense of choose, go over again or consider carefully. The definition of ''religio'' by [[Cicero]] is ''cultum deorum'', "the proper performance of rites in veneration of the gods."<ref>Cicero, ''De natura deorum'' II, 28.</ref> Julius Caesar used ''religio'' to mean "obligation of an oath" when discussing captured soldiers making an oath to their captors.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Caesar |first1=Julius |translator-last1=McDevitte |translator-first1=W.A. |translator-first2=W.S. |translator-last2=Bohn |title=The Works of Julius Caesar: Parallel English and Latin |date=2007 |publisher=Forgotten Books |isbn=978-1-60506-355-3 |pages=377–378 |chapter=Civil Wars – Book 1|quote= Sic terror oblatus a ducibus, crudelitas in supplicio, nova religio iurisiurandi spem praesentis deditionis sustulit mentesque militum convertit et rem ad pristinam belli rationem redegit." – (Latin); "Thus the terror raised by the generals, the cruelty and punishments, the new obligation of an oath, removed all hopes of surrender for the present, changed the soldiers' minds, and reduced matters to the former state of war."- (English)}}</ref> The Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder used the term ''religio'' on elephants in that they venerate the sun and the moon.<ref>{{cite book |author1=Pliny the Elder |chapter=Elephants; Their Capacity |title=The Natural History, Book VIII |chapter-url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.02.0137%3Abook%3D8%3Achapter%3D1 |publisher=Tufts University |language=en |quote={{lang-la|maximum est elephans proximumque humanis sensibus, quippe intellectus illis sermonis patrii et imperiorum obedientia, officiorum quae didicere memoria, amoris et gloriae voluptas, immo vero, quae etiam in homine rara, probitas, prudentia, aequitas, religio quoque siderum solisque ac lunae veneratio.}}" "The elephant is the largest of them all, and in intelligence approaches the nearest to man. It understands the language of its country, it obeys commands, and it remembers all the duties which it has been taught. It is sensible alike of the pleasures of love and glory, and, to a degree that is rare among men even, possesses notions of honesty, prudence, and equity; it has a religious respect also for the stars, and a veneration for the sun and the moon."}}</ref> Modern scholars such as [[Tom Harpur]] and [[Joseph Campbell]] favor the derivation from ''{{lang|la|ligare}}'' bind, connect, probably from a prefixed ''{{lang|la|re-ligare}}'', i.e. ''re'' (again) + ''ligare'' or to reconnect, which was made prominent by [[Augustine of Hippo|St. Augustine]], following the interpretation given by [[Lactantius]] in ''Divinae institutiones'', IV, 28.<ref>In ''The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light.'' Toronto. Thomas Allen, 2004. {{ISBN|0-88762-145-7}}</ref><ref>In ''[[The Power of Myth]],'' with Bill Moyers, ed. Betty Sue Flowers, New York, Anchor Books, 1991. {{ISBN|0-385-41886-8}}</ref> The medieval usage alternates with ''order'' in designating bonded communities like those of [[monastic orders]]: "we hear of the 'religion' of the [[Order of the Golden Fleece|Golden Fleece]], of a knight 'of the [[Order of Aviz|religion of Avys]]'".<ref name="Huizinga Middle">{{cite book |last1=Huizinga |first1=Johan |title=The Waning of the Middle Ages |date=1924 |publisher=Penguin Books |page=86|title-link=The Autumn of the Middle Ages }}</ref>

| |

|

| |

|

| In classic antiquity, 'religio' broadly meant conscientiousness, sense of right, moral obligation, or duty to anything.<ref>{{cite web |title=Religio |url=https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0060%3Aentry%3Dreligio |website=Latin Word Study Tool |publisher=Tufts University}}</ref> In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root ''religio'' was understood as an individual virtue of worship in mundane contexts; never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.<ref name="Harrison Territories" /><ref name="Roberts Jon">{{cite book|last1=Roberts|first1=Jon|editor1-last=Shank|editor1-first=MIchael|editor2-last=Numbers|editor2-first=Ronald|editor3-last=Harrison|editor3-first=Peter|title=Wrestling with Nature: From Omens to Science|date=2011|publisher=University of Chicago Press|location=Chicago|isbn=978-0-226-31783-0|page=254|chapter=10. Science and Religion}}</ref> In general, ''religio'' referred to broad social obligations towards anything including family, neighbors, rulers, and even towards God.<ref name="50 great" /> ''Religio'' was most often used by the ancient Romans not in the context of a relation towards gods, but as a range of general emotions such as hesitation, caution, anxiety, fear; feelings of being bound, restricted, inhibited; which arose from heightened attention in any mundane context.<ref name="religio roman">{{cite book |last1=Barton |first1=Carlin |last2=Boyarin |first2=Daniel |title=Imagine No Religion : How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient Realities |date=2016 |publisher=Fordham University Press |isbn=978-0-8232-7120-7 |chapter=1. 'Religio' without "Religion" |pages=15–38}}</ref> The term was also closely related to other terms like ''scrupulus'' which meant "very precisely" and some Roman authors related the term ''superstitio'', which meant too much fear or anxiety or shame, to ''religio'' at times.<ref name="religio roman" /> When ''religio'' came into English around the 1200s as religion, it took the meaning of "life bound by monastic vows" or monastic orders.<ref name="Huizinga Middle" /><ref name="50 great" /> The compartmentalized concept of religion, where religious things were separated from worldly things, was not used before the 1500s.<ref name="50 great" /> The concept of religion was first used in the 1500s to distinguish the domain of the church and the domain of civil authorities.<ref name="50 great">{{cite book|last1=Morreall|first1=John|last2=Sonn|first2=Tamara|title=50 Great Myths about Religions|date=2013|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-0-470-67350-8|pages=12–17|chapter=Myth 1: All Societies Have Religions}}</ref>

| | === Human spirit === |

| | | Another main belief is that humans have a "soul" or spirit which lives on after their body has died. The person's spirit is on a journey through life that continues after death. Most religions believe that what a person does during their lifetime will affect what happens to their spirit in the [[afterlife]]. Many religions teach that a good person's spirit can reach a special place of peace and happiness such as [[Heaven]] or [[Nirvana]], and that a bad person's spirit can travel to a place of pain and suffering such as [[Hell]]. Still other religions believe in [[reincarnation]] - that instead of going either to Heaven or Hell, spirits of the dead return to earth in a new body. |

| In the ancient Greece, the Greek term ''threskeia'' was loosely translated into Latin as ''religio'' in late antiquity. The term was sparsely used in classical Greece but became more frequently used in the writings of Josephus in the first century CE. It was used in mundane contexts and could mean multiple things from respectful fear to excessive or harmfully distracting practices of others; to cultic practices. It was often contrasted with the Greek word ''deisidaimonia'' which meant too much fear.<ref name="threskeia greece">{{cite book |last1=Barton |first1=Carlin |last2=Boyarin |first2=Daniel |title=Imagine No Religion : How Modern Abstractions Hide Ancient Realities |date=2016 |publisher=Fordham University Press |isbn=978-0-8232-7120-7 |chapter=8. Imagine No 'Threskeia': The Task of the Untranslator |pages=123–134}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| The modern concept of religion, as an abstraction that entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines, is a recent invention in the English language. Such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to events such as the splitting of [[Christendom]] during the [[Protestant Reformation]] and globalization in the age of exploration, which involved contact with numerous foreign cultures with non-European languages.<ref name="Harrison Territories">{{cite book |last1=Harrison |first1=Peter |title=The Territories of Science and Religion |date=2015 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-18448-7}}</ref><ref name="Roberts Jon" /><ref name="Religion enlightenment">{{cite book|last1=Harrison|first1=Peter|title='Religion' and the Religions in the English Enlightenment|date=1990|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|isbn=978-0-521-89293-3}}</ref>

| |

| Some argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply the term religion to non-Western cultures.<ref name=dubuisson>{{cite book|first1=Daniel|last1=Dubuisson|title=The Western Construction of Religion : Myths, Knowledge, and Ideology|date=2007|publisher=Johns Hopkins University Press|location=Baltimore, Md.|isbn=978-0-8018-8756-7}}</ref><ref name="Fitzgerald"/> Others argue that using religion on non-Western cultures distorts what people do and believe.<ref name="Smith Meaning and End">{{cite book|last1=Smith|first1=Wilfred Cantwell |title=The Meaning and End of Religion|date=1991|publisher=Fortress Press|location=Minneapolis|isbn=978-0-8006-2475-0}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| The concept of religion was formed in the 16th and 17th centuries,<ref name=Nongbri1>{{cite book |last1=Nongbri |first1=Brent |title=Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept|page=152 |quote=Although the Greeks, Romans, Mesopotamians, and many other peoples have long histories, the stories of their respective religions are of recent pedigree. The formation of ancient religions as objects of study coincided with the formation of religion itself as a concept of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.|date=2013 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-15416-0}}</ref><ref name="Religion enlightenment1">{{cite book|last1=Harrison|first1=Peter|title='Religion' and the Religions in the English Enlightenment|url=https://archive.org/details/religionreligion00harr|url-access=limited|date=1990|publisher=Cambridge University Press|location=Cambridge|page=[https://archive.org/details/religionreligion00harr/page/n11 1]|isbn=978-0-521-89293-3|quote=That there exist in the world such entities as 'the religions' is an uncontroversial claim...However, it was not always so. The concepts 'religion' and 'the religions', as we presently understand them, emerged quite late in Western thought, during the Enlightenment. Between them, these two notions provided a new framework for classifying particular aspects of human life.}}</ref> despite the fact that ancient sacred texts like the Bible, the Quran, and others did not have a word or even a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Nongbri |first1=Brent |title=Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept |chapter=2. Lost in Translation: Inserting "Religion" into Ancient Texts |date=2013 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-15416-0}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Morreall|first1=John|last2=Sonn|first2=Tamara|title=50 Great Myths about Religions|date=2013|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-0-470-67350-8|page=13|quote=Many languages do not even have a word equivalent to our word 'religion'; nor is such a word found in either the Bible or the Qur'an.}}</ref> For example, there is no precise equivalent of religion in Hebrew, and [[Judaism]] does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.<ref>Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, [https://www.questia.com/library/book/history-of-zionism-a-handbook-and-dictionary-by-abfaham-j-edelheit-hershel-edelheit.jsp History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary], p. 3, citing [[Solomon Zeitlin]], ''The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion?'' (Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).</ref> One of its central concepts is ''[[halakha]]'', meaning the walk or path sometimes translated as law, which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.<ref name="WhitefordII2008">{{cite book |last1=Whiteford |first1=Linda M. |last2=Trotter II |first2=Robert T. |title=Ethics for Anthropological Research and Practice |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=ZeokAAAAQBAJ&pg=PA22 |year=2008 |publisher=Waveland Press |isbn=978-1-4786-1059-5 |page=22}}</ref> Even though the beliefs and traditions of Judaism are found in the ancient world, ancient Jews saw Jewish identity as being about an ethnic or national identity and did not entail a compulsory belief system or regulated rituals.<ref name="Burns Jewish">{{cite book|last1=Burns|first1=Joshua Ezra|editor1-last=Omar|editor1-first=Irfan|editor2-last=Duffey|editor2-first=Michael|title=Peacemaking and the Challenge of Violence in World Religions|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-1-118-95342-6|chapter=3. Jewish ideologies of Peace and Peacemaking|pages=86–87|date=2015-06-22}}</ref> Even in the 1st century CE, Josephus had used the Greek term ''ioudaismos'', which some translate as Judaism today, even though he used it as an ethnic term, not one linked to modern abstract concepts of religion as a set of beliefs.<ref name=Nongbri /> It was in the 19th century that Jews began to see their ancestral culture as a religion analogous to Christianity.<ref name="Burns Jewish" /> The Greek word ''threskeia'', which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus, is found in the New Testament. ''Threskeia'' is sometimes translated as religion in today's translations, however, the term was understood as worship well into the medieval period.<ref name=Nongbri>{{cite book |last1=Nongbri |first1=Brent |title=Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept |date=2013 |publisher=Yale University Press |isbn=978-0-300-15416-0}}</ref> In the Quran, the Arabic word ''[[Din (Arabic)|din]]'' is often translated as religion in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed ''din'' as law.<ref name=Nongbri />

| |

| | |

| The [[Sanskrit]] word [[dharma]], sometimes translated as religion,<ref name="14.1A: The Nature of Religion">{{cite web |title=14.1A: The Nature of Religion |url=https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Sociology/Book%3A_Sociology_(Boundless)/14%3A_Religion/14.01%3A_The_Nature_of_Religion/14.1A%3A_The_Nature_of_Religion#:~:text=For%20example%2C%20the%20Sanskrit%20word,and%20ceremonial%20and%20practical%20traditions.&text=Some%20religions%20place%20an%20emphasis%20on%20belief%20while%20others%20emphasize%20practice. |website=Social Sci LibreTexts |access-date=10 January 2021 |language=en |date=15 August 2018}}</ref> also means law. Throughout classical [[South Asia]], the [[Dharmaśāstra|study of law]] consisted of concepts such as [[Prāyaścitta|penance through piety]] and [[Ācāra|ceremonial as well as practical traditions]]. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between imperial law and universal or Buddha law, but these later became independent sources of power.<ref>{{cite journal |first=Toshio |last=Kuroda |author-link=Toshio Kuroda |translator=Jacqueline I. Stone |url=http://www.nanzan-u.ac.jp/SHUBUNKEN/publications/jjrs/pdf/477.pdf |title=The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law |access-date=2010-05-28 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20030323095019/http://www.nanzan-u.ac.jp/SHUBUNKEN/publications/jjrs/pdf/477.pdf |archive-date=23 March 2003 |journal=Japanese Journal of Religious Studies |pages= 23.3–4 |date=1996}}</ref><ref>Neil McMullin. ''Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan''. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Though traditions, sacred texts, and practices have existed throughout time, most cultures did not align with Western conceptions of religion since they did not separate everyday life from the sacred. In the 18th and 19th centuries, the terms Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Confucianism, and [[world religions]] first entered the English language.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Harrison |first1=Peter |title=The Territories of Science and Religion |date=2015|page=101 |quote=The first recorded use of "Boudhism" was 1801, followed by "Hindooism" (1829), "Taouism" (1838), and "Confucianism" (1862) (see figure 6). By the middle of the nineteenth century these terms had secured their place in the English lexicon, and the putative objects to which they referred became permanent features of our understanding of the world. |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-18448-7}}</ref><ref>{{cite book |last1=Josephson |first1=Jason Ananda |title=The Invention of Religion in Japan |date=2012 |page=12|quote=The early nineteenth century saw the emergence of much of this terminology, including the formation of the terms Boudhism (1801), Hindooism (1829), Taouism (1839), Zoroastri-anism (1854), and Confucianism (1862). This construction of "religions" was not merely the production of European translation terms, but the reification of systems of thought in a way strikingly divorced from their original cultural milieu. The original discovery of religions in different cultures was rooted in the assumption that each people had its own divine "revelation," or at least its own parallel to Christianity. In the same period, however, European and American explorers often suggested that specific African or Native American tribes lacked religion altogether. Instead these groups were reputed to have only superstitions and as such they were seen as less than human.|publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-41234-4}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|last1=Morreall|first1=John|last2=Sonn|first2=Tamara|title=50 Great Myths about Religions|date=2013|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-0-470-67350-8|page=12|quote=The phrase "World Religions" came into use when the first Parliament of the World's Religions was held in Chicago in 1893. Representation at the Parliament was not comprehensive. Naturally, Christians dominated the meeting, and Jews were represented. Muslims were represented by a single American Muslim. The enormously diverse traditions of India were represented by a single teacher, while three teachers represented the arguably more homogenous strains of Buddhist thought. The indigenous religions of the Americas and Africa were not represented. Nevertheless, since the convening of the Parliament, Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, Confucianism, and Taoism have been commonly identified as World Religions. They are sometimes called the "Big Seven" in Religious Studies textbooks, and many generalizations about religion have been derived from them.}}</ref> No one self-identified as a Hindu or Buddhist or other similar terms before the 1800s.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Morreall|first1=John|last2=Sonn|first2=Tamara|title=50 Great Myths about Religions|date=2013|publisher=Wiley-Blackwell|isbn=978-0-470-67350-8|page=14|quote=Before the British colonized India, for example, the people there had no concept "religion" and no concept "Hinduism." There was no word "Hindu" in classical India, and no one spoke of "Hinduism" until the 1800s. Until the introduction of that term, Indians identified themselves by any number of criteria—family, trade or profession, or social level, and perhaps the scriptures they followed or the particular deity or deities upon whose care they relied in various contexts or to whom they were devoted. But these diverse identities were united, each an integral part of life; no part existed in a separate sphere identified as "religious." Nor were the diverse traditions lumped together under the term "Hinduism" unified by sharing such common features of religion as a single founder, creed, theology, or institutional organization.}}</ref> "Hindu" has historically been used as a geographical, cultural, and later religious identifier for people indigenous to the [[Indian subcontinent]].<ref name=brian111>{{citation|last=Pennington|first=Brian K.|title=Was Hinduism Invented?: Britons, Indians, and the Colonial Construction of Religion|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=7drluePK-acC&pg=PA111|year=2005|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-803729-3|pages=111–118}}</ref><ref>{{cite book|author=Lloyd Ridgeon|title=Major World Religions: From Their Origins to the Present|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=HFKBAgAAQBAJ |year= 2003|publisher= Routledge|isbn=978-1-134-42935-6|pages=10–11}}, Quote: "It is often said that Hinduism is very ancient, and in a sense this is true (...). It was formed by adding the English suffix -ism, of Greek origin, to the word ''Hindu'', of Persian origin; it was about the same time that the word ''Hindu'', without the suffix -ism, came to be used mainly as a religious term. (...) The name ''Hindu'' was first a geographical name, not a religious one, and it originated in the languages of Iran, not of India. (...) They referred to the non-Muslim majority, together with their culture, as 'Hindu'. (...) Since the people called Hindu differed from Muslims most notably in religion, the word came to have religious implications, and to denote a group of people who were identifiable by their Hindu religion. (...) However, it is a religious term that the word ''Hindu'' is now used in English, and Hinduism is the name of a religion, although, as we have seen, we should beware of any false impression of uniformity that this might give us."</ref> Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of religion since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this idea.<ref name="Invention Japan">{{cite book |last1=Josephson |first1=Jason Ananda |title=The Invention of Religion in Japan |date=2012 |pages=1, 11–12 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |isbn=978-0-226-41234-4}}</ref><ref name="japan Galen">{{cite book|last1=Zuckerman|first1=Phil|last2=Galen|first2=Luke|last3=Pasquale|first3=Frank|title=The Nonreligious: Understanding Secular People and Societies|date=2016|publisher=Oxford University Press|isbn=978-0-19-992494-3|pages=39–40|chapter=2. Secularity around the World|quote=It was only in response to Western cultural contact in the late nineteenth century that a Japanese word for religion (shukyo) came into use. It tends to be associated with foreign, founded, or formally organized traditions, particularly Christianity and other monotheisms, but also Buddhism and new religious sects.}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| According to the [[philologist]] [[Max Müller]] in the 19th century, the root of the English word religion, the [[Latin]] ''[[:wikt:religio|religio]]'', was originally used to mean only reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, [[pietas|piety]] (which [[Cicero]] further derived to mean diligence).<ref>[[Max Müller]], ''Natural Religion'', p. 33, 1889</ref><ref>[https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.04.0059%3Aentry%3D%2340976 Lewis & Short, ''A Latin Dictionary'']</ref> [[Max Müller]] characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called law.<ref>[[Max Müller]]. ''[https://books.google.com/books?pg=PA28&id=aM0FAAAAQAAJ&as_brr=4 Introduction to the science of religion]''. p. 28.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Definition==

| |

| [[File:16 religionist symbols.png|thumb|Religious symbols from left to right, top to bottom: [[Christianity]], [[Islam]], [[Hinduism]], [[Buddhism]], [[Judaism]], the [[Baháʼí Faith]], [[Eckankar]], [[Sikhism]], [[Jainism]], [[Wicca]], [[Unitarian Universalism]], [[Shinto]], [[Taoism]], [[Thelema]], [[Tenrikyo]], and [[Zoroastrianism]]]]

| |

| {{Main|Definition of religion}}

| |

| Scholars have failed to agree on a definition of religion. There are, however, two general definition systems: the sociological/functional and the phenomenological/philosophical.<ref>Vgl. Johann Figl: ''Handbuch Religionswissenschaft: Religionen und ihre zentralen Themen.'' Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, {{ISBN|3-7022-2508-0}}, S. 65.</ref><ref>Julia Haslinger: ''Die Evolution der Religionen und der Religiosität,'' s. [[Religion#Religionsgeschichte|Literatur Religionsgeschichte]], S. 3–4, 8.</ref><ref>Johann Figl: ''Handbuch Religionswissenschaft: Religionen und ihre zentralen Themen.'' Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2003, {{ISBN|3-7022-2508-0}}, S. 67.</ref><ref>In: Friedrich Schleichermacher: ''Der christliche Glaube nach den Grundsätzen der evangelischen Kirche.'' Berlin 1821/22. Neuausg. Berlin 1984, § 3/4. Zit. nach: [[Walter Burkert]]: ''Kulte des Altertums. Biologische Grundlagen der Religion.'' 2. Auflage. C.H. Beck, München 2009, {{ISBN|978-3-406-43355-9}}, S. 102.</ref><ref>Peter Antes: ''Religion, religionswissenschaftlich.'' In: EKL Bd. 3, Sp. 1543. S. 98.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Modern Western===

| |

| The concept of religion originated in the [[modern era|modern]] [[Western culture|Western]] era.<ref name="Fitzgerald">{{Cite book|first=Timothy|last=Fitzgerald|title=Discourse on Civility and Barbarity|url=https://archive.org/details/discourseoncivil00fitz|url-access=limited|publisher=Oxford University Press|year=2007|pages=[https://archive.org/details/discourseoncivil00fitz/page/n57 45]–46}}</ref> Parallel concepts are not found in many current and past cultures; there is no equivalent term for religion in many languages.<ref name="Nongbri" /><ref name="50 great" /> Scholars have found it difficult to develop a consistent definition, with some giving up on the possibility of a definition.<ref>McKinnon, AM. 2002). [http://aura.abdn.ac.uk/bitstream/2164/3073/1/McKinnon_Definition_of_Religion_author_version_no_format.pdf "Sociological Definitions, Language Games and the 'Essence' of Religion"]. ''Method & Theory in the Study of Religion'', vol 14, no. 1, pp. 61–83.</ref><ref>Josephson, Jason Ānanda. (2012) ''The Invention of Religion in Japan.'' Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 257</ref> Others argue that regardless of its definition, it is not appropriate to apply it to non-Western cultures.<ref name="dubuisson"/><ref name="Fitzgerald"/>

| |

| | |

| An increasing number of scholars have expressed reservations about ever defining the essence of religion.<ref>{{cite journal | last=McKinnon | first=A.M. |date=2002 |title=Sociological definitions, language games, and the 'essence' of religion | journal=Method & Theory in the Study of Religion | volume=14 | issue=1 | issn=0943-3058 | doi=10.1163/157006802760198776 | pages=61–83 |url=http://aura.abdn.ac.uk/bitstream/2164/3073/1/McKinnon_Definition_of_Religion_author_version_no_format.pdf |access-date=20 July 2017| citeseerx=10.1.1.613.6995 }}</ref> They observe that the way we use the concept today is a particularly modern construct that would not have been understood through much of history and in many cultures outside the West (or even in the West until after the [[Peace of Westphalia]]).<ref>{{cite book |last=Smith |first=Wilfred Cantwell |date=1978 |title=The Meaning and End of Religion |location=New York |publisher=Harper and Row}}</ref> The MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions states:

| |

| {{quote|The very attempt to define religion, to find some distinctive or possibly unique essence or set of qualities that distinguish the religious from the remainder of human life, is primarily a Western concern. The attempt is a natural consequence of the Western speculative, intellectualistic, and scientific disposition. It is also the product of the dominant Western religious mode, what is called the Judeo-Christian climate or, more accurately, the theistic inheritance from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The theistic form of belief in this tradition, even when downgraded culturally, is formative of the [[dichotomy|dichotomous]] Western view of religion. That is, the basic structure of theism is essentially a distinction between a transcendent deity and all else, between the creator and his creation, between God and man.<ref>{{cite encyclopedia |last=King |first=W.L. |date=2005 |article=Religion (First Edition) |editor-link=Mircea Eliade |editor-first=Mircea |editor-last=Eliade |title=The Encyclopedia of Religion |publisher=[[Gale (publisher)|MacMillan Reference US]] |edition=2nd |page=7692}}</ref>}}

| |

| | |

| The anthropologist [[Clifford Geertz]] defined religion as a

| |

| {{quote|[…] system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic."{{sfn|Geertz|1993|pp=87–125}}}}

| |

| | |

| Alluding perhaps to Tylor's "deeper motive", Geertz remarked that

| |

| {{quote|[…] we have very little idea of how, in empirical terms, this particular miracle is accomplished. We just know that it is done, annually, weekly, daily, for some people almost hourly; and we have an enormous ethnographic literature to demonstrate it.{{sfn|Geertz|1993|p=90}}}}

| |

| | |

| The theologian [[Antoine Vergote]] took the term supernatural simply to mean whatever transcends the powers of nature or human agency. He also emphasized the cultural reality of religion, which he defined as

| |

| {{quote|[…] the entirety of the linguistic expressions, emotions and, actions and signs that refer to a supernatural being or supernatural beings.<ref name="vergote">Vergote, A. (1996) ''Religion, Belief and Unbelief. A Psychological Study'', Leuven University Press. (p. 16)</ref>}}

| |

| | |

| [[Peter Mandaville]] and [[Paul James (academic)|Paul James]] intended to get away from the modernist dualisms or dichotomous understandings of immanence/transcendence, spirituality/materialism, and sacredness/secularity. They define religion as

| |

| {{quote|[…] a relatively-bounded system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and in which communion with others and Otherness is ''lived'' as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.<ref name="Paul James and Peter Mandaville 2010" />}}

| |

| | |

| According to the MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions, there is an experiential aspect to religion which can be found in almost every culture:

| |

| {{quote|[…] almost every known culture [has] a depth dimension in cultural experiences […] toward some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life. When more or less distinct patterns of behavior are built around this depth dimension in a culture, this structure constitutes religion in its historically recognizable form. Religion is the organization of life around the depth dimensions of experience—varied in form, completeness, and clarity in accordance with the environing culture.<ref>MacMillan Encyclopedia of religions, ''Religion'', p. 7695</ref>}}

| |

| | |

| ===Classical===

| |

| [[File:Будажап Цыреторов.JPG|thumb|Budazhap Shiretorov (Будажап Цыреторов), the head shaman of the religious community Altan Serge (Алтан Сэргэ) in [[Buryatia]].]]

| |

| [[Friedrich Schleiermacher]] in the late 18th century defined religion as ''das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl'', commonly translated as "the feeling of absolute dependence".<ref>{{Cite journal |doi=10.1017/S0034412504007462|title='Feeling of absolute dependence' or 'absolute feeling of dependence'? A question revisited|journal=Religious Studies|volume=41|pages=81–94|year=2005|last1=Finlay|first1=Hueston E.}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| His contemporary [[Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel]] disagreed thoroughly, defining religion as "the Divine Spirit becoming conscious of Himself through the finite spirit."<ref>[[Max Müller]]. "Lectures on the origin and growth of religion."</ref>

| |

| | |

| [[Edward Burnett Tylor]] defined religion in 1871 as "the belief in spiritual beings".<ref name="archive.org">Tylor, E.B. (1871) ''[https://archive.org/stream/primitiveculture1tylouoft#page/424/mode/2up Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. Vol. 1]''. London: John Murray; (p. 424).</ref> He argued that narrowing the definition to mean the belief in a supreme deity or judgment after death or [[idolatry]] and so on, would exclude many peoples from the category of religious, and thus "has the fault of identifying religion rather with particular developments than with the deeper motive which underlies them". He also argued that the belief in spiritual beings exists in all known societies.

| |

| | |

| In his book ''[[The Varieties of Religious Experience]]'', the psychologist [[William James]] defined religion as "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine".{{sfn|James|1902|p=31}} By the term divine James meant "any object that is god''like'', whether it be a concrete deity or not"{{sfn|James|1902|p=34}} to which the individual feels impelled to respond with solemnity and gravity.{{sfn|James|1902|p=38}}

| |

| | |

| The sociologist [[Émile Durkheim]], in his seminal book ''[[The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life]]'', defined religion as a "unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things".{{sfn|Durkheim|1915|p=}} By sacred things he meant things "set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them". Sacred things are not, however, limited to gods or spirits.<ref group=note>That is how, according to Durkheim, Buddhism is a religion. "In default of gods, Buddhism admits the existence of sacred things, namely, the [[Four Noble Truths|four noble truths]] and the practices derived from them" {{harvnb|Durkheim|1915|p=}}</ref> On the contrary, a sacred thing can be "a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred".{{sfn|Durkheim|1915|p=37}} Religious beliefs, myths, dogmas and legends are the representations that express the nature of these sacred things, and the virtues and powers which are attributed to them.{{sfn|Durkheim|1915|pp=40–41}}

| |

| | |

| Echoes of James' and Durkheim's definitions are to be found in the writings of, for example, [[Frederick Ferré]] who defined religion as "one's way of valuing most comprehensively and intensively".<ref>Frederick Ferré, F. (1967) ''Basic modern philosophy of religion''. Scribner, (p. 82).</ref> Similarly, for the theologian [[Paul Tillich]], faith is "the state of being ultimately concerned",<ref name="Tillich, P. 1957 p.1"/> which "is itself religion. Religion is the substance, the ground, and the depth of man's spiritual life."<ref>Tillich, P. (1959) ''Theology of Culture''. Oxford University Press; (p. 8).</ref>

| |

| | |

| When religion is seen in terms of sacred, divine, intensive valuing, or ultimate concern, then it is possible to understand why scientific findings and philosophical criticisms (e.g., those made by [[Richard Dawkins]]) do not necessarily disturb its adherents.<ref>Pecorino, P.A. (2001) [http://www2.sunysuffolk.edu/pecorip/scccweb/etexts/phil_of_religion_text/CHAPTER_10_DEFINITION/The-Definition-of-Religion.htm ''Philosophy of Religion. Online Textbook''] {{webarchive|url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130619213234/http://www2.sunysuffolk.edu/pecorip/scccweb/etexts/phil_of_religion_text/CHAPTER_10_DEFINITION/The-Definition-of-Religion.htm |date=19 June 2013 }}. Philip A. Pecorino.</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Aspects==

| |

| | |

| ===Beliefs===

| |

| {{Main|Religious beliefs}}

| |

| Traditionally, [[faith]], in addition to reason, has been considered a source of religious beliefs. The interplay between faith and reason, and their use as perceived support for religious beliefs, have been a subject of interest to philosophers and theologians.<ref name="iep.utm.edu"/> The origin of religious belief as such is an open question, with possible explanations including awareness of individual death, a sense of community, and dreams.<ref>{{cite magazine |last=Zeigler |first=David |date=January–February 2020 |title=Religious Belief from Dreams? |magazine=[[Skeptical Inquirer]] |location=Amherst, N.Y. |publisher=[[Center for Inquiry]] |volume=44 |issue=1 |pages=51–54}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| ====Mythology====

| |

| {{Main|Mythology}}

| |

| The word ''myth'' has several meanings.

| |

| # A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

| |

| # A person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence; or

| |

| # A metaphor for the spiritual potentiality in the human being.<ref>Joseph Campbell, ''The Power of Myth'', p. 22 {{ISBN|0-385-24774-5}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Ancient [[polytheism|polytheistic]] religions, such as those of [[Ancient Greece|Greece]], [[Ancient Rome|Rome]], and [[Scandinavia]], are usually categorized under the heading of [[mythology]]. Religions of pre-industrial peoples, or [[culture]]s in development, are similarly called myths in the [[anthropology of religion]]. The term myth can be used pejoratively by both religious and non-religious people. By defining another person's religious stories and beliefs as mythology, one implies that they are less real or true than one's own religious stories and beliefs. [[Joseph Campbell]] remarked, "Mythology is often thought of as ''other people's'' religions, and religion can be defined as mis-interpreted mythology."<ref>Joseph Campbell, ''Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor''. Ed. Eugene Kennedy. New World Library {{ISBN|1-57731-202-3}}.</ref>

| |

| | |

| In sociology, however, the term myth has a non-pejorative meaning. There, myth is defined as a story that is important for the group whether or not it is objectively or provably true.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.britannica.com/topic/myth|title=myth|website=Encyclopædia Britannica|access-date=24 April 2016}}</ref> Examples include the [[resurrection]] of their real-life founder [[Jesus]], which, to Christians, explains the means by which they are freed from sin, is symbolic of the power of life over death, and is also said to be a historical event. But from a mythological outlook, whether or not the event actually occurred is unimportant. Instead, the [[symbol]]ism of the death of an old life and the start of a new life is what is most significant. Religious believers may or may not accept such symbolic interpretations.

| |

| | |

| ===Practices===

| |

| {{Main|Religious behaviour|Cult (religious practice)}}

| |

| The practices of a religion may include [[ritual]]s, [[sermon]]s, commemoration or veneration (of a [[deity]], [[God (male deity)|gods]], or [[goddess]]es), [[sacrifice]]s, [[festival]]s, [[Banquet|feasts]], [[trance]]s, [[initiation]]s, [[funeral|funerary services]], [[matrimony|matrimonial services]], [[meditation]], [[prayer]], [[religious music]], [[religious art]], [[sacred dance]], [[Community service|public service]], or other aspects of human culture.<ref name="OD">[http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/mythology Oxford Dictionaries] mythology, retrieved 9 September 2012</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Social organisation===

| |

| Religions have a societal basis, either as a living tradition which is carried by lay participants, or with an organized [[clergy]], and a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership.

| |

| | |

| ==Academic study==

| |

| {{Main|Religious studies|Classifications of religious movements}}

| |

| A number of disciplines study the phenomenon of religion: [[theology]], [[comparative religion]], [[history of religion]], [[evolutionary origin of religions]], [[anthropology of religion]], [[psychology of religion]] (including [[neurotheology|neuroscience of religion]] and [[evolutionary psychology of religion]]), [[law and religion]], and [[sociology of religion]].

| |

| | |

| Daniel L. Pals mentions eight classical theories of religion, focusing on various aspects of religion: [[animism]] and [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]], by [[Edward Burnett Tylor|E.B. Tylor]] and [[J.G. Frazer]]; the [[Psychoanalysis|psycho-analytic]] approach of [[Sigmund Freud]]; and further [[Émile Durkheim]], [[Karl Marx]], [[Max Weber]], [[Mircea Eliade]], [[E.E. Evans-Pritchard]], and [[Clifford Geertz]].{{sfn|Pals|2006}}

| |

| | |

| [[Michael Stausberg]] gives an overview of contemporary theories of religion, including [[Cognitive science of religion|cognitive]] and biological approaches.{{sfn|Stausberg|2009}}

| |

| | |

| ===Theories===

| |

| {{Main|Theories of religion}}

| |

| [[Sociology of religion|Sociological]] and [[Anthropology of religion|anthropological]] theories of religion generally attempt to explain the [[origin of religion|origin]] and [[social function|function of religion]].<ref>{{harvnb|Segal|2005|p=49}}</ref> These theories define what they present as universal characteristics of [[religious belief]] and [[Religious behaviour|practice]].

| |

| | |

| ====Origins and development====

| |

| {{Main|History of religion}}

| |

| [[File:Yazilikaya B 12erGruppe.jpg|thumb|upright=1.15|The [[Yazılıkaya]] sanctuary in [[Turkey]], with the twelve gods of the underworld]]

| |

| The origin of religion is uncertain. There are a number of theories regarding the subsequent origins of religious practices.

| |

| | |

| According to [[anthropologists]] John Monaghan and Peter Just, "Many of the great world religions appear to have begun as revitalization movements of some sort, as the vision of a charismatic prophet fires the imaginations of people seeking a more comprehensive answer to their problems than they feel is provided by everyday beliefs. Charismatic individuals have emerged at many times and places in the world. It seems that the key to long-term success—and many movements come and go with little long-term effect—has relatively little to do with the prophets, who appear with surprising regularity, but more to do with the development of a group of supporters who are able to institutionalize the movement."<ref>{{cite book |title=Social & Cultural Anthropology |url=https://archive.org/details/socialculturalan00mona |url-access=limited |last1=Monaghan |first1=John |last2=Just |first2=Peter |year=2000 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New York |isbn=978-0-19-285346-2 |page=[https://archive.org/details/socialculturalan00mona/page/n136 126]}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| The [[development of religion]] has taken different forms in different cultures. Some religions place an emphasis on belief, while others emphasize practice. Some religions focus on the subjective experience of the religious individual, while others consider the activities of the religious community to be most important. Some religions claim to be universal, believing their [[law]]s and [[cosmology]] to be binding for everyone, while others are intended to be practiced only by a closely defined or localized group. In many places, religion has been associated with public institutions such as [[education]], [[hospital]]s, the [[family]], [[government]], and [[politics|political]] hierarchies.<ref name=autogenerated1>{{cite book |title=Social & Cultural Anthropology |url=https://archive.org/details/socialculturalan00mona |url-access=limited |last1=Monaghan |first1=John |last2=Just |first2=Peter |year=2000 |publisher=Oxford University Press |location=New York |isbn=978-0-19-285346-2 |page=[https://archive.org/details/socialculturalan00mona/page/n134 124]}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Anthropologists John Monoghan and Peter Just state that, "it seems apparent that one thing religion or belief helps us do is deal with problems of human life that are significant, persistent, and intolerable. One important way in which religious beliefs accomplish this is by providing a set of ideas about how and why the world is put together that allows people to accommodate anxieties and deal with misfortune."<ref name=autogenerated1 />

| |

| | |

| ====Cultural system====

| |

| While religion is difficult to define, one standard model of religion, used in [[religious studies]] courses, was proposed by [[Clifford Geertz]], who simply called it a "cultural system".<ref>Clifford Geertz, ''Religion as a Cultural System'', 1973</ref> A critique of Geertz's model by [[Talal Asad]] categorized religion as "an [[anthropology|anthropological]] category".<ref>Talal Asad, ''The Construction of Religion as an Anthropological Category'', 1982.</ref> Richard Niebuhr's (1894–1962) five-fold classification of the relationship between Christ and culture, however, indicates that religion and culture can be seen as two separate systems, though not without some interplay.<ref>Richard Niebuhr, ''Christ and Culture'' (San Francisco: Harper & Row, 1951) as cited by Domenic Marbaniang, "The Gospel and Culture: Areas of Conflict, Consent, and Conversion", ''Journal of Contemporary Christian'' Vol. 6, No. 1 (Bangalore: CFCC, Aug 2014), {{ISSN|2231-5233}} pp. 9–10</ref>

| |

| | |

| ====Social constructionism====

| |

| {{Main|Theories about religions#Social constructionism|l1=Social constructionism}}

| |

| One modern academic theory of religion, [[social constructionism]], says that religion is a modern concept that suggests all [[spirituality|spiritual]] practice and [[worship]] follows a model similar to the [[Abrahamic religions]] as an orientation system that helps to interpret reality and define human beings.<ref name="vergote 89">Vergote, Antoine, ''Religion, belief and unbelief: a psychological study'', Leuven University Press, 1997, p. 89</ref> Among the main proponents of this theory of religion are Daniel Dubuisson, Timothy Fitzgerald, Talal Asad, and Jason Ānanda Josephson. The social constructionists argue that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

| |

| | |

| ====Cognitive science====

| |

| {{Main|Cognitive science of religion}}

| |

| | |

| Cognitive science of religion is the study of religious thought and behavior from the perspective of the cognitive and evolutionary sciences.<ref>{{cite web |last1=Barrett |first1=Justin L. |title=Cognitive Science of Religion: What Is It and Why Is It? |url=https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1749-8171.2007.00042.x |website=Religion Compass |access-date=10 January 2021 |pages=768–786 |language=en |doi=10.1111/j.1749-8171.2007.00042.x |date=2007}}</ref> The field employs methods and theories from a very broad range of disciplines, including: [[cognitive psychology]], [[evolutionary psychology]], [[cognitive anthropology]], [[artificial intelligence]], [[cognitive neuroscience]], [[neurobiology]], [[zoology]], and [[ethology]]. Scholars in this field seek to explain how human minds acquire, generate, and transmit religious thoughts, practices, and schemas by means of ordinary cognitive capacities.

| |

| | |

| Hallucinations and delusions related to religious content occurs in about 60% of people with [[schizophrenia]]. While this number varies across cultures, this had led to theories about a number of influential religious phenomenon and possible relation to psychotic disorders. A number of prophetic experiences are consistent with psychotic symptoms, although retrospective diagnoses are practically impossible.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Nicholson|first1=PT|title=Psychosis and paroxysmal visions in the lives of the founders of world religions.|journal=The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences|volume=26|issue=1|date=2014|pages=E13–14|doi=10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12120412|pmid=24515692}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Murray|first1=ED|last2=Cunningham|first2=MG|last3=Price|first3=BH|title=The role of psychotic disorders in religious history considered.|journal=The Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences|volume=24|issue=4|date=2012|pages=410–426|doi=10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11090214|pmid=23224447}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Weber|first1=SR|last2=Pargament|first2=KI|title=The role of religion and spirituality in mental health.|journal=Current Opinion in Psychiatry|date=September 2014|volume=27|issue=5|pages=358–363|doi=10.1097/YCO.0000000000000080|pmid=25046080|s2cid=9075314}}</ref> Schizophrenic episodes are also experienced by people who do not have belief in gods.<ref>{{cite journal|last1=Reina|first1=Aaron|title=Faith Within Atheism|journal=Schizophrenia Bulletin|date=July 2014|volume=40|issue=4|pages=719–720|doi=10.1093/schbul/sbt076|pmid=23760918|pmc=4059423}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| Religious content is also common in [[temporal lobe epilepsy]], and [[obsessive-compulsive disorder]].<ref>{{cite book|last1=Favazza|first1=A|editor1-last=Sadock|editor1-first=B|editor2-last=Sadock|editor2-first=V|editor3-last=Ruiz|editor3-first=P|title=Kaplan and Sadocks Comprehensive Texbook of Psychiatry|publisher=Wolters Kluwer|edition=10th|chapter=Psychiatry and Spirituality}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal|last1=Altschuler|first1=EL|title=Temporal lobe epilepsy in the priestly source of the Pentateuch|journal=South African Medical Journal|date=2004|volume=11|issue=94|page=870|pmid=15587438}}</ref> Atheistic content is also found to be common with temporal lobe epilepsy.<ref name="Heilman">{{cite book|last1=Heilman|first1=Kenneth M.|last2=Valenstein|first2=Edward |title=Clinical Neuropsychology|date=2011|publisher=Oxford University Press|language=en|isbn=978-0-19-538487-1|page=488|quote=Studies that claim to show no difference in emotional makeup between temporal lobe and other epileptic patients (Guerrant et. al., 1962; Stevens, 1966) have been reinterpreted (Blumer, 1975) to indicate that there is, in fact, a difference: those with temporal lobe epilepsy are more likely to have more serious forms of emotional disturbance. This typical personality of temporal lobe epileptic patient has been described in roughly similar terms over many years (Blumer & Benson, 1975; Geschwind, 1975, 1977; Blumer, 1999; Devinsky & Schachter, 2009). These patients are said to have a deepening of emotions; they ascribe great significance to commonplace events. This can be manifested as a tendency to take a cosmic view; hyperreligiosity (or intensely professed atheism) is said to be common.}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Comparativism===

| |

| {{Main|Comparative religion}}

| |

| Comparative religion is the branch of the [[study of religions]] concerned with the systematic comparison of the doctrines and practices of the world's religions. In general, the comparative study of religion yields a deeper understanding of the fundamental philosophical concerns of religion such as [[ethics]], [[metaphysics]], and the nature and form of [[salvation]]. Studying such material is meant to give one a richer and more sophisticated understanding of human beliefs and practices regarding the [[sacred]], [[numinous]], [[spirituality|spiritual]] and [[Divinity|divine]].<ref>"Human beings' relation to that which they regard as holy, sacred, spiritual, and divine" [[Encyclopædia Britannica]] (online, 2006), cited after {{cite web |url=http://www.religionfacts.com/religion/quotes.htm |title=Definitions of Religion |website=Religion facts}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| In the field of comparative religion, a common geographical classification<ref name="EB" /> of the [[Major religious groups|main world religions]] includes [[Middle Eastern religions]] (including [[Zoroastrianism]] and [[Iranian religions]]), [[Indian religions]], [[East Asian religions]], African religions, American religions, Oceanic religions, and classical Hellenistic religions.<ref name="EB">[http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/497215/classification-of-religions/38029/Normative Charles Joseph Adams, ''Classification of religions: geographical'', Encyclopædia Britannica]</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Classification==

| |

| {{Main||History of religion}}

| |

| [[File:Prevailing world religions map.png|thumb|upright=2.05|A map of [[List of religious populations|major denominations and religions of the world]]]]

| |

| In the 19th and 20th centuries, the academic practice of [[comparative religion]] divided religious belief into philosophically defined categories called world religions. Some academics [[Study of religion|studying the subject]] have divided religions into three broad categories:

| |

| # [[world religions]], a term which refers to [[Transculturation|transcultural]], international religions;

| |

| # [[indigenous religions]], which refers to smaller, culture-specific or nation-specific religious groups; and

| |

| # [[new religious movements]], which refers to recently developed religions.<ref>Harvey, Graham (2000). ''Indigenous Religions: A Companion''. (Ed: Graham Harvey). London and New York: Cassell. p. 6.</ref>

| |

| | |

| Some recent scholarship has argued that not all types of religion are necessarily separated by mutually exclusive philosophies, and furthermore that the utility of ascribing a practice to a certain philosophy, or even calling a given practice religious, rather than cultural, political, or social in nature, is limited.<ref name="pennington">Brian Kemble Pennington ''Was Hinduism Invented?'' New York: Oxford University Press US, 2005. {{ISBN|0-19-516655-8}}</ref><ref>Russell T. McCutcheon. ''Critics Not Caretakers: Redescribing the Public Study of Religion''. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.</ref><ref>Nicholas Lash. ''The beginning and the end of 'religion'.'' Cambridge University Press, 1996. {{ISBN|0-521-56635-5}}</ref> The current state of psychological study about the nature of religiousness suggests that it is better to refer to religion as a largely invariant phenomenon that should be distinguished from cultural norms (i.e. religions).<ref>Joseph Bulbulia. "Are There Any Religions? An Evolutionary Explanation." ''Method & Theory in the Study of Religion'' 17.2 (2005), pp. 71–100</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Morphological classification===

| |

| Some scholars classify religions as either ''[[Universalizing religion|universal religions]]'' that seek worldwide acceptance and actively look for new converts, or ''[[ethnic religion]]s'' that are identified with a particular ethnic group and do not seek converts.<ref name="Hinnells">{{Cite book |title=The Routledge companion to the study of religion |last=Hinnells |first=John R. |year=2005 |publisher=Routledge |isbn=978-0-415-33311-5 |pages=439–440 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=IGspjXKxIf8C |access-date=17 September 2009}}</ref> Others reject the distinction, pointing out that all religious practices, whatever their philosophical origin, are ethnic because they come from a particular culture.<ref>Timothy Fitzgerald. ''The Ideology of Religious Studies''. New York: Oxford University Press US, 2000.</ref><ref>Craig R. Prentiss. ''Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity''. New York: NYU Press, 2003. {{ISBN|0-8147-6701-X}}</ref><ref>Tomoko Masuzawa. ''The Invention of World Religions, or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. {{ISBN|0-226-50988-5}}</ref> Christianity, Islam, Buddhism and Jainism are universal religions while Hinduism and Judaism are ethnic religions.<ref>https://www.soas.ac.uk/ijjs/archive/file32517.pdf</ref>

| |

| | |

| ===Demographical classification===

| |

| {{Main|Major religious groups|List of religious populations}}

| |

| The five largest religious groups by world population, estimated to account for 5.8 billion people and 84% of the population, are Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism (with the relative numbers for Buddhism and Hinduism dependent on the extent of [[syncretism]]) and traditional folk religion.

| |

| | |

| {| class="wikitable sortable"

| |

| |+

| |

| |- style="background:#666688;"

| |

| ! Five largest religions

| |

| ! 2010 (billion)<ref name="EB2012">{{cite web |url=http://www.pewforum.org/2012/12/18/global-religious-landscape-exec/ |title=The Global Religious Landscape |access-date=18 December 2012|date=2012-12-18 }}</ref>

| |

| ! 2010 (%)

| |

| ! 2000 (billion)<ref name="EB2000">{{cite encyclopedia |last=Turner |first=Darrell J. |url=http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/715463/Religion-Year-In-Review-2000 |title=Religion: Year In Review 2000 |encyclopedia=Encyclopædia Britannica |access-date=16 June 2012}}</ref><ref>but cf: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/#religions</ref>

| |

| ! 2000 (%)

| |

| ! Demographics

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | [[Christianity]]

| |

| | 2.2

| |

| | 32%

| |

| | 2.0

| |

| | 33%

| |

| | [[Christianity by country]]

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | [[Islam]]

| |

| | 1.6

| |

| | 23%

| |

| | 1.2

| |

| | 19.6%

| |

| | [[List of countries by Muslim population|Islam by country]]

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | [[Hinduism]]

| |

| | 1.0

| |

| | 15%

| |

| | 0.811

| |

| | 13.4%

| |

| | [[Hinduism by country]]

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | [[Buddhism]]

| |

| | 0.5

| |

| | 7%

| |

| | 0.360

| |

| | 5.9%

| |

| | [[Buddhism by country]]

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | [[Folk religion]]

| |

| | 0.4

| |

| | 6%

| |

| | 0.385

| |

| | 6.4%

| |

| |

| |

| |- style="text-align:center; background:#e0e8ee;"

| |

| | Total

| |

| | 5.8

| |

| | 84%

| |

| | 4.8

| |

| | 78.3%

| |

| |

| |

| |}

| |

| | |

| A global poll in 2012 surveyed 57 countries and reported that 59% of the world's population identified as religious, 23% as [[irreligion|not religious]], 13% as convinced [[atheism|atheists]], and also a 9% decrease in identification as religious when compared to the 2005 average from 39 countries.<ref name="gia">{{cite web |url= http://www.wingia.com/web/files/richeditor/filemanager/Global_INDEX_of_Religiosity_and_Atheism_PR__6.pdf |title= Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism |publisher= WIN-Gallup International |date= 27 July 2012 |access-date= 24 August 2012 |url-status=dead |archive-url= https://web.archive.org/web/20120906165952/http://www.wingia.com/web/files/richeditor/filemanager/Global_INDEX_of_Religiosity_and_Atheism_PR__6.pdf |archive-date= 6 September 2012}}</ref> A follow-up poll in 2015 found that 63% of the globe identified as religious, 22% as not religious, and 11% as convinced atheists.<ref name=GallupInt2015>{{cite web|title=Losing our Religion? Two-Thirds of People Still Claim to be Religious|url=http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/290/file/290.pdf|website=WIN/Gallup International|publisher=WIN/Gallup International|date=13 April 2015|url-status=dead|archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20150430232945/http://www.wingia.com/web/files/news/290/file/290.pdf|archive-date=30 April 2015}}</ref> On average, women are more religious than men.<ref>{{cite web|url=http://www.livescience.com/7689-women-religious-men.html|title=Women More Religious Than Men|work=Livescience.com|access-date=14 July 2013}}</ref> Some people follow multiple religions or multiple religious principles at the same time, regardless of whether or not the religious principles they follow traditionally allow for [[syncretism]].<ref>Soul Searching:The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers – p. 77, Christian Smith, Melina Lundquist Denton – 2005</ref><ref>Christ in Japanese Culture: Theological Themes in Shusaku Endo's Literary Works, Emi Mase-Hasegawa – 2008

| |

| </ref><ref>

| |

| [http://www.christianpost.com/news/new-poll-reveals-how-churchgoers-mix-eastern-new-age-beliefs-42215/ New poll reveals how churchgoers mix eastern new age beliefs] retrieved 26 July 2013

| |

| </ref> A 2017 [[Pew Research Center|Pew]] projection suggests that Islam will overtake Christianity as the plurality religion by 2075. Unaffiliated populations are projected to drop, even when taking disaffiliation rates into account, due to differences in birth rates.<ref>{{cite news |title=Islam set to become world's largest religion by 2075, study suggests |url=https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/apr/05/muslim-population-overtake-christian-birthrate-20-years |access-date=20 March 2021 |work=the Guardian |date=5 April 2017 |language=en}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |title=The Changing Global Religious Landscape |url=https://www.pewforum.org/2017/04/05/the-changing-global-religious-landscape/ |access-date=21 March 2021 |work=[[Pew Research Center]]'s Religion & Public Life Project |date=5 April 2017}}</ref>

| |

| | |

| ==Specific religions==

| |

| {{Main|List of religions and spiritual traditions}}

| |

| | |

| ===Abrahamic===

| |

| [[File:Molnár_Ábrahám_kiköltözése_1850.jpg|thumb|The patriarch [[Abraham]] (by [[József Molnár (painter)|József Molnár]])]]

| |

| [[Abrahamic religions]] are [[monotheistic]] religions which believe they descend from [[Abraham]].

| |

| | |

| ====Judaism====

| |

| [[File:Open_Torah_and_pointer.jpg|thumb|The [[Torah]] is the primary sacred text of Judaism.]]

| |

| [[Judaism]] is the oldest Abrahamic religion, originating in the people of [[History of ancient Israel and Judah|ancient Israel and Judea]].<ref name="britannica.com">{{cite web |title=Judaism {{!}} Definition, Origin, History, Beliefs, & Facts |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Judaism |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=10 January 2021 |language=en}}</ref> The [[Torah]] is its foundational text, and is part of the larger text known as the [[Tanakh]] or [[Hebrew Bible]]. It is supplemented by oral tradition, set down in written form in later texts such as the [[Midrash]] and the [[Talmud]]. Judaism includes a wide corpus of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization. Within Judaism there are a variety of movements, most of which emerged from [[Rabbinic Judaism]], which holds that God revealed his laws and [[613 Mitzvot|commandments]] to [[Moses]] on [[Biblical Mount Sinai|Mount Sinai]] in the form of both the [[Torah|Written]] and [[Oral Torah]]; historically, this assertion was challenged by various groups. The [[Jewish people]] were scattered after the destruction of the [[Temple in Jerusalem]] in 70 CE. Today there are about 13 million Jews, about 40 per cent living in Israel and 40 per cent in the United States.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton61/st02_27.pdf |title=Info |website=www.cbs.gov.il |access-date=22 March 2011 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20111026202909/http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton61/st02_27.pdf |archive-date=26 October 2011 |url-status=dead }}</ref> The largest [[Jewish religious movements]] are [[Orthodox Judaism]] ([[Haredi Judaism]] and [[Modern Orthodox Judaism]]), [[Conservative Judaism]] and [[Reform Judaism]].<ref name="britannica.com"/>

| |

| | |

| ====Christianity====

| |

| [[File:ISR-2013-Jerusalem-Holy_Sepulchre-dome.jpg|thumb|Jesus is the central figure of Christianity.]]

| |

| [[Christianity]] is based on the life and teachings of [[Jesus of Nazareth]] (1st century) as presented in the [[New Testament]].<ref name="Christianity">{{cite web |title=Christianity {{!}} Definition, Origin, History, Beliefs, Symbols, Types, & Facts |url=https://www.britannica.com/topic/Christianity |website=Encyclopedia Britannica |access-date=10 January 2021 |language=en}}</ref> The Christian faith is essentially faith in Jesus as the [[Christ]],<ref name="Christianity"/> the [[Son of God]], and as [[Messiah|Savior]] and Lord. Almost all Christians believe in the [[Trinity]], which teaches the unity of [[God the Father|Father]], [[God the Son|Son]] (Jesus Christ), and [[Holy Spirit]] as three persons in [[monotheism|one Godhead]]. Most Christians can describe their faith with the [[Nicene Creed]]. As the religion of [[Byzantine Empire]] in the first millennium and of [[Western Europe]] during the time of colonization, Christianity has been propagated throughout the world via [[Christian mission|missionary work]].<ref name="Spread">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=g2AtOlJMPTUC&pg=PA52|title =Muslim-Christian Relations|publisher = Amsterdam University Press|quote=The enthusiasm for evangelization among the Christians was also accompanied by the awareness that the most immediate problem to solve was how to serve the huge number of new [[Conversion to Christianity|converts]]. Simatupang said, if the number of the Christians were double or triple, then the number of the ministers should also be doubled or tripled and the role of the laity should be maximized and Christian service to society through schools, universities, hospitals and orphanages, should be increased. In addition, for him the Christian mission should be involved in the struggle for justice amid the process of modernization.|access-date = 18 October 2007|isbn = 978-90-5356-938-2|year = 2006}}</ref><ref name="Charity">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=WmuV6g0yR3sC&pg=PA77|page=77|author=Fred Kammer|title =Doing Faith Justice|publisher = [[Paulist Press]]|quote=Theologians, bishops, and preachers urged the Christian community to be as compassionate as their God was, reiterating that creation was for all of humanity. They also accepted and developed the identification of Christ with the poor and the requisite Christian duty to the poor. Religious congregations and individual charismatic leaders promoted the development of a number of helping institutions-hospitals, hospices for [[Christian pilgrimage|pilgrims]], orphanages, shelters for unwed mothers-that laid the foundation for the modern "large network of hospitals, orphanages and schools, to serve the poor and society at large."|access-date = 18 October 2007|isbn = 978-0-8091-4227-9|date = 1 May 2004}}</ref><ref name="Service">{{cite book|url = https://books.google.com/books?id=dz_EM2ofIb4C&pg=PA132|title =Christian Church Women: Shapers of a Movement|publisher = Chalice Press|quote=In the central provinces of India they established schools, orphanages, hospitals, and churches, and spread the gospel message in zenanas.|access-date = 18 October 2007|isbn = 978-0-8272-0463-8|date = March 1994}}</ref> It is the [[Major religious groups|world's largest religion]], with about 2.3 billion followers as of 2015.<ref>{{Cite web|url=http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/04/05/christians-remain-worlds-largest-religious-group-but-they-are-declining-in-europe/|title=World's largest religion by population is still Christianity|website=Pew Research Center|language=en-US|access-date=27 February 2019}}</ref> The main divisions of Christianity are, according to the number of adherents:<ref name="history.com">{{cite web |last1=Editors |first1=History com |title=Christianity |url=https://www.history.com/topics/religion/history-of-christianity#:~:text=Christianity%20is%20broadly%20split%20into,Catholic%20bishops%20around%20the%20world. |website=HISTORY |access-date=10 January 2021 |language=en}}</ref>

| |

| * The [[Catholic Church]], led by the [[Bishop of Rome]] and the bishops worldwide in communion with him, is a [[Communion (Christian)|communion]] of 24 Churches ''[[sui iuris]]'', including the [[Latin Church]] and 23 [[Eastern Catholic Churches|Eastern Catholic churches]], such as the [[Maronite]] Catholic Church.<ref name="history.com"/>

| |