Gupta–Hunnic Wars: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| (14 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 46: | Line 46: | ||

| commander2 = 3 unknown [[Hephthalites|Hepthalite]] kings{{POW}} & {{executed}} (possibly)<ref>"The young son of Mahendrasena led his father's army of two hundred thousand men against the enemy whose soldiers numbered three hundred thousand. The prince however, broke the enemy army and won the battle. On his return his father crown him saying "henceforth rule the kingdom," and himself retired to religious life. For twelve years after this, the new king fought these foreign enemies, and ultimately captured and executed the three kings.' It has been suggested that this story gives an account of the fight between [[Skandagupta]] and the [[Hunas|Hūṇas]] (IHIJ. 36)." {{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4ZYwAAAAMAAJ |title=The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age |date=1951 |publisher=G. Allen & Unwin |language=en |page=27}}</ref><br />Khingila I<br />Piro<br />Bhūta<br />Bharatbala<br />[[Toramana]]<br />[[Mihirakula]] {{POW}}<br />Prakasaditya<br />Harigupta<br />Dhanyavishnu | | commander2 = 3 unknown [[Hephthalites|Hepthalite]] kings{{POW}} & {{executed}} (possibly)<ref>"The young son of Mahendrasena led his father's army of two hundred thousand men against the enemy whose soldiers numbered three hundred thousand. The prince however, broke the enemy army and won the battle. On his return his father crown him saying "henceforth rule the kingdom," and himself retired to religious life. For twelve years after this, the new king fought these foreign enemies, and ultimately captured and executed the three kings.' It has been suggested that this story gives an account of the fight between [[Skandagupta]] and the [[Hunas|Hūṇas]] (IHIJ. 36)." {{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=4ZYwAAAAMAAJ |title=The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age |date=1951 |publisher=G. Allen & Unwin |language=en |page=27}}</ref><br />Khingila I<br />Piro<br />Bhūta<br />Bharatbala<br />[[Toramana]]<br />[[Mihirakula]] {{POW}}<br />Prakasaditya<br />Harigupta<br />Dhanyavishnu | ||

}} | }} | ||

== Background == | |||

{{Main|Campaigns of Samudragupta}} | |||

=== Samudragupta's Āryāvarta campaigns === | |||

[[File:Allahabad Pillar by Joseph Tiefenthaler, 18th Century.jpg|thumb|Allahabad Pillar by Joseph Tiefenthaler, 18th Century]] | |||

According to the [[Allahabad Pillar]] inscription, Samudragupta "forcibly uprooted" the following kings of [[Aryavarta]], the northern region:{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=114}} | |||

{{columns-list|colwidth=30em| | |||

# Rudradeva | |||

# Matila | |||

# Nagadatta | |||

# Chandravarman | |||

# Ganapatinaga | |||

# Nagasena | |||

# Achyuta-nandin | |||

# Balavarman | |||

}} | |||

Unlike the southern kings, the inscription does not mention the territories ruled by these kings, which suggests that their kingdoms were annexed to the Gupta empire.{{sfn|R. C. Majumdar|1981|p=22}} The inscription also mentions that Samudragupta defeated some other kings, but does not mention their names, presumably because the poet saw them as unimportant.{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=114}} | |||

=== Rise of Kidara Kushans === | |||

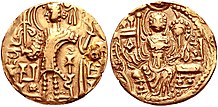

[[File:HUNNIC TRIBES Kidarites Kidara Circa CE 350-385.jpg|thumb|upright=1.31|[[Kidara]] gold coin, circa 350–385, derived from the [[Kushans]]. Vertical [[Brahmi]] legends from right to left: ''Kushana'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|14px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|14px]] ''Ku-shā-ṇa'') ''Kidara'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ki.jpg|16px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad d.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka r.svg|14px]] ''Ki-da-ra'') ''Kushana'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|14px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|14px]] ''Ku-shā-ṇa''). Enthroned goddess [[Ardoxsho]] on the back.]] | |||

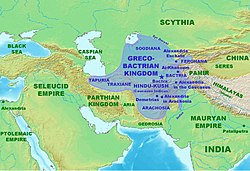

The emergence of the Great Kushans in [[Bactria]] and [[Northwest India|Northwestern India]] during the first century A.D. transformed these regions into significant players in international politics. The [[Kushan empire]] posed a dual threat to the [[Parthians]] of [[Iran]]. Economically, the Kushans, like the Parthians, acted as intermediaries in trade. They controlled three crucial sections of the renowned Silk Road: firstly, the route connecting the [[Caspian Sea|Caspian]] and [[Euxine]] Seas; secondly, the path passing through [[Merv]], [[Hecatompylos]], and [[Ecbatana]], crossing the [[Euphrates]] and reaching [[Mediterranean]] ports; and thirdly, the maritime route between [[India]] and the [[Red Sea]], which gained immense importance after the discovery of monsoons. Consequently, they had the ability to redirect trade between [[China]], [[India]], and the eastern countries away from [[Parthian Empire|Parthian]] territory, posing a significant economic challenge to [[Parthian Empire|Parthian]] rulers.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=169}} | |||

The political implications of the Kushans' rise as a major power were also profound for Iran. Instead of facing a single enemy in the West, Iran found itself sandwiched between the [[Roman Empire]] and the Kushans. The Romans, who were constantly engaged in rivalry and conflict with the Parthians, recognized the strategic importance of this empire and sought direct relations with its rulers to safeguard trade routes between [[Rome]], [[China]], and [[India]]. Caught between these two powers, the early [[Sasanians]], who succeeded the Parthians as the imperial rulers of Iran in 224 A.D., made the conquest of the Kushan empire their primary objective in Eastern policy, and they achieved remarkable success in this endeavor. The first Sasanian emperor, [[Ardashir I]] (224-241 A.D.), conquered Kushan principalities to the north of the [[Hindukush]]. Although Kushan chiefs continued to govern these territories, they had to accept the overlordship of the Sasanian emperor.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=169}} | |||

=== Submission of Kidarites (Little Kushans) === | |||

[[File:Kushana in Brahmi script (diagonal).jpg|thumb|[[Kushana]] in [[Brahmi script]] (diagonal)]] | |||

The [[Kushan Empire]] continued as a remnant known as the "Little Kushans", based in the [[Punjab]]. Around 270 their territories on the Gangetic plain became independent under local dynasties such as the [[Yaudheyas]]. Then in the mid-4th century they were subjugated by the [[Gupta Empire]] under [[Samudragupta]].<ref name="HCCA166">{{harvnb|Dani |Litvinsky |Zamir Safi|1996|pp=[https://books.google.com/books?id=883OZBe2sMYC&pg=PA165 165]–[https://books.google.com/books?id=883OZBe2sMYC&pg=PA166 166]}}</ref> In his inscription on the [[Allahabad pillar]] Samudragupta proclaims that the ''Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi'' (referring to the last Kushan rulers, being a deformation of the Kushan regnal titles ''Devaputra'', ''Shao'' and ''Shaonanoshao'': "Son of God, King, King of Kings") are now under his dominion, and that they were forced to "self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces".<ref>Lines 23-24 of the [[Allahabad pillar]] inscription of Samudragupta: "Self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces through the Garuḍa badge, by the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi and the Śaka lords and by (rulers) occupying all Island countries, such as Siṁhala and others."</ref><ref name="HCCA166" /><ref>{{cite journal |last1=Cribb |first1=Joe |last2=Singh |first2=Karan |title=Two Curious Kidarite Coin Types From 3rd Century Kashmir |journal=JONS |volume=230 |date=Winter 2017 |page=3 |url=https://www.academia.edu/36983254}}</ref> This suggests that by the time of the Allahabad inscription the [[Kushans]] still ruled in [[Punjab]], but under the suzerainty of the Gupta Emperor.<ref name="HCCA166" /> | |||

=== North-western policy of Samudragupta === | |||

[[File:Kidara coin.jpg|thumb|upright=1.36|[[Kidara]], circa 425–457. AR Drachm (29 mm, 3.76 g, 3h). Mint C in [[Gandhara]]. Crowned bust facing slightly right. [[Brahmi]] legend around the head: [[File:Gupta allahabad ki.jpg|13px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka d.svg|13px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad r.svg|13px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|15px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|13px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|13px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|13px]] ''Ki-da-ra Ku-ṣa-ṇa-ṣa''/ Fire altar flanked by attendants.<ref>[https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=359788 A similar coin with reading of the legend]</ref> The use of the 3/4 portrait is sometimes attributed to the influence of [[:File:Arcadius.gif|the coinage]] of [[Byzantine Empire]] ruler [[Arcadius]] (377–408 CE).<ref>{{cite book |last1=Lerner |first1=Judith A. |title=Observations on the Typology and Style of Seals and Sealings from Bactria and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands, in Coins, Art and Chronology II. The First Millennium CE in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands |date=210 |publisher=ÖAW |location=Vienna |page=246, note 7 |url=https://www.academia.edu/743914 |language=en}}</ref>]] | |||

The reconstruction of Samudragupta's northwest policy mentioned earlier aligns with other intriguing facts. In 361 AD, an [[India]]n delegation reportedly visited [[Rome]], as stated by [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] historians. Despite having been dispatched from [[India]] earlier, the embassy did not reach [[Rome]] until 351 AD. Taking into account the political circumstances in [[India]] during the mid-4th century AD, this fact holds significant value. Before the year 361 AD, it was noted that the [[Ancient Rome|Roman]] emperors were engaged in a conflict with the [[Sassanids]]. Hence, it was not unexpected for Samudragupta to try to stop future conflicts with the [[Persia]]n army on the Western Front by allying with [[Kidara I]] against [[Shahpur II]]. Hence, it is possible that he dispatched an embassy to [[Rome]] prior to 361 AD.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=179-180}} | |||

Additionally, considering the political background of [[Bactria]] and [[Northwest India|north-west India]] described earlier, it is more probable that [[Kalidasa]] authored the Digvijaya story of Raghu using the real events resulting from Samudragupta's conquest, assuming great force. [[Kalidasa]] stated that Raghu conquered the [[Deccan]]'s [[Trikuta]]s before heading overland to conquer the Parasikas. Having emerged victorious over them, he went on to conquer the Hunas before launching an assault on the [[Kambojas]]. The Parasikas mentioned by [[Kalidasa]] are evidently related to the [[Sasanians]]. He mentioned that the [[Hunas]] resided by the Vankshu or [[Oxus]] river. During the third quarter of the fourth century AD, this was exactly the area where they resided. Ultimately, it may be concluded that the [[Kambojas]] of [[Raghuvamsa]] are likely to be the same as [[Kidarites|Kidara Kushans]], as historical evidence shows that Kidara Inot only conquered [[Gandhara]] but also the five neighboring kingdoms, of course which were in Kambojas.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=179-180}} | |||

=== Gupta-Kidara alliance === | |||

[[File:Kidara I portrait.jpg|thumb|upright=1|left|Portrait of [[Kidara]], king of the [[Kidarites]], circa 350–386. The coinage of the Kidarites imitated [[Sasanian coinage|Sasanian imperial coinage]], with the exception that they displayed clean-shaven faces, instead of the beards of the Sasanians, a feature relating them to [[Altaic]] rather than [[Iranian peoples|Iranian]] lineage.<ref name="Maas">The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 [https://books.google.com/books?id=e0dcBAAAQBAJ&pg=PA284 p.284sq]</ref><ref>Encyclopaedia Iranica, article Kidarites: "On Gandhāran coins bearing their name the ruler is always clean-shaven, a fashion more typical of Altaic people than of Iranians" in {{cite journal |title=KIDARITES – Encyclopaedia Iranica |website=www.iranicaonline.org |url=http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/kidarites}}</ref>]] | |||

The [[Kushan Empire|Kushan]] contemporary of [[Samudragupta]], was [[Kidara I|Kidāra]]. He was initially a part of the Great [[Kushan Empire|Kushan]] family. It was after him that his individuals got to be celebrated as the small [[Kushans]]. Hence, it can be promptly conceded that he was known to his counterparts as a ruler of the Devaputra family. But he was not effective enough to utilize the title Shahanushahi. He was simply a Shahi. His coins bearing the legend 'Kidāra Kushāṇa Shāhi' proved it. Subsequently, he can be effectively recognized with Daivaputrashāhi of the [[Allahabad]] pillar inscription. Here it is curiously to note that opposite to the for the most part acknowledged see, within the Prayaga Prasasti the word Devaputra has not been utilized as a title, for the reality that it has been utilized in its taddhita shape not simply appears that it must be taken in conjunction with the another word 'Shāhi', it moreover demonstrates that the compound Daivaputrashahi would connote 'Shāhi, who had a place to (the family of) the Devaputras'. As respects [[Kidara I|Kidāra's]] contemporary Shahanushahi, he might have been no other than [[Shapur II]], the [[Sassanian]] Shahanshah. On the premise of this proposal the course of history of [[Bactria]] and [[Northwest India|North-Western India]] may be reproduced as takes after: | |||

[[File:Kushano-Sasanian Vahrām (Bahram) I Balkh mint Struck under Kidarite king Kidara circa CE 350-365.jpg|thumb|[[Kushano-Sasanian Kingdom|Kushano-Sasanian]] Vahrām (Bahram) I [[Balkh]] mint Struck under [[Kidarite]] king [[Kidara I]] circa CE 350-365]] | |||

[[Kidara I|Kidara]], after having set up himself in [[Gandhara]], apparently at the cost of the [[Saka]] rulers, drew closer to [[Samudragupta]] a few times after 359 A. D., sent him presents and callings of steadfastness and inquired for his offer of assistance against the [[Sasanians]]. [[Samudragupta]], on his part, was exceptionally much on edge to amplify his circle of impact past the central [[Punjab]] where his subordinate partners, the Gadaharas, were administering. He saw with uneasiness the tribal developments which were taking place in that heading and were posturing a risk to his recently established domain. But he was not a vanquisher, he was a statesman as well. He knew he possessed impediments and had the intelligence of restoring the prevailed rulers of the South.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=177-178}} | |||

He needed to be included in a North-Western experience, indeed less. But, in any case, he was anxious to make the wildernesses of the domain and the western trade-routes secure and secure. He subsequently, did what was the most excellent; beneath the circumstances he concluded an alliance with [[Kidara I|Kidara]] and as the more grounded part of the association gave him an offer of assistance against [[Shapur II]]. His arrangement was prominently effective and [[Kidara I|Kidara]] vanquished the [[Sasanians]] twice in 367-68 A. D. It may not suggest that Shapur II got to be a vassal of [[Kidara I|Kidara]] or [[Samudragupta]]. But it does indicate that the articulation of Harishena about the connection of his master with the [[Sasanian]] ruler ought to not be suggested as through and through altogether without foundation.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=177-178}} | |||

=== First Hephthalite invasion === | |||

[[File:Ebodalo (Bactrian cursive and Greek standard).jpg|thumb|upright|left|The [[Hephthalites]] used the [[Bactrian script]] (top), an adaptation of the [[Greek script]] (bottom). Here, their [[endonym]] ''Ebodalo'', "Hephthalites".]] | |||

[[Kidara I|Kidara]], thereafter the year 367-68 A. D., likely in c. 370 A. D. had to bargain with the attack of the Jouan-Jouan or Hiung-nu or the [[White Huns]] from [[Bactria]] or [[Valhika]]. He put his son within the charge of his capital and went towards west to meet the intruders. This time too, [[Samudragupta]] shows up to have given considerable assistance to his [[Kushan Empire|Kushan]] ally. As a matter of truth, the victory of [[Kidara I|Kidara]] against the [[Hunas]], whom he seem not check prior when he was in [[Bactria]], demonstrates that this time he had an effective partner on his side. In this way, a fruitful endeavor by the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] sovereign in c. 370 A. D. against the [[Valhikas]] 'across the seven mouths of the river [[Indus]]' gets to be a really solid plausibility. It is one of the reasons which have driven us to hypothesize the identicality of the lord 'Chandra' with [[Samudragupta]]. It may, in any case, be recollected that the history of [[Bactria]] and the [[Northwest India|North-Western India]] as laid out over does not depend upon the recognizable proof of [[Samudragupta]] with the ruler of the [[Mehrauli|Meharauli]] inscription. For example, in case we are to incline toward the hypothesis of the distinguishing proof of [[Chandragupta II]] with the ruler of this record, we can assume that it was [[Chandragupta II|Chandragupta]], the offspring of [[Samudragupta]], was the one sent as the pioneer of this expedition.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=178-179}} | |||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=300|caption_align=center | |||

| align = right | |||

| direction =horizontal | |||

| image1 = Bandian, vanquished Hephthalite (vertical).jpg | |||

| image2 = Bandian Hephthalite.jpg | |||

| footer=The Hephthalites as vanquished enemies (face down on the floor), and then as allies (seated), in the Sasanian [[Bandian complex]]. The inscription next to the seated ruler reads: "I am Hephthalite, son … the Hephthalite is trustworthy".<ref>{{cite book |last1=KURBANOV |first1=AYDOGDY |title=THE HEPHTHALITES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS |date=2010 |publisher=Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Free University |location=Berlin |page=39 |url=https://www.podgorski.com/main/assets/documents/Hephthalites_Kurbanov.pdf}}</ref><ref name="Oxford University Press">{{cite book |last1=Potts |first1=Daniel T. |title=Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era |date=2014 |publisher=Oxford University Press |isbn=978-0-19-933079-9 |page=137 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=8c3QAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA137 |language=en}}</ref> 459-497 CE | |||

}} | |||

=== Geographical factors in North-western policy === | |||

[[File:India 500 AD.jpg|Charles Joppen's construction in 1907 of possible Indian map in 500 AD|thumb]] | |||

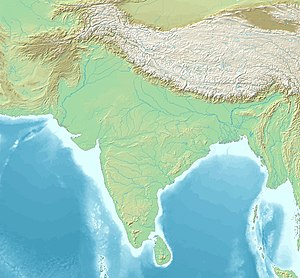

The general station of the ancient conglomerate-builders of the [[Ganga]] Valley towards the North-West was conditioned by the interplay of several factors. Geographically, the [[Indus]] valley is the western of cornucopia of what may be called the Fertile Crescent of [[India]], and gives the print that it's nearly connected with the [[Ganga]] Valley. But there's another side of this picture also. It may be noted and needs to be emphasized that the [[Indus]] river-system is not only unconnected with any other river of [[North India]], but it's indeed separated from the rest of the country by the vast desert of [[Thar Desert|Thar]]. The stretch of the home which connects it with the [[Ganga]] Valley viz.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=280-281}} | |||

The [[Thanesar]]-[[Delhi]]-[[Kurukshetra]] division–roughly the ancient realm of the [[Kuru (kingdom)|Kuru Kingdom]]-is veritably narrow and communication through it was rendered delicate in the ancient times by the great timbers, similar as the [[Khandava]], Kāmākhyā, Kurujāngala and Dvaitavana and also by a large number of small gutters. These walls, it seems, rendered the subjection of the Indus receptacle by the powers of the [[Ganga]] Valley relatively delicate and made these two regions to appear more distant and remote from each other than they actually were. It's a literal fact that with the exception of the [[Mauryas]], nearly all the conglomerate-builders of the [[Ganga]] Valley the [[Nandas]], the [[Sungas]], the [[Naga people|Nagas]], the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] and indeed the [[Vardhanas]] noway seriously tried to conquer the region to the west of the Divide.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=280-281}} | |||

It doesn't mean that they noway took any interest in the political fortunes of the Indus receptacle; they couldn't go to neglect it altogether. piecemeal from the fact that this region also belonged to the larger [[India]]n world and, thus, the achievement of universal sovereignty (chakravartitra) was regarded as deficient without establishing some kind of suzerainty over it, they could hardly forget that utmost of the routes of the [[India]]n trade with the Western countries were controlled by the North-Western powers. Above all, the nearly constant affluence via the [[Indus]] receptacle of Central and Western Asiatic peoples who relatively constantly hovered the security of the [[antarvedi]] itself, impelled them to take note of the political developments in the Indus receptacle. But these lodestones weren't sufficient enough to bait them to take over wars of subjection in that region.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=280-281}} | |||

The [[Vardhanas]], though a power of [[Thanesar]], were interested in it only to the extent of transferring occasional peregrinations against the [[Hunas]]; the Sungas communicated some interest only when they were hovered by the [[Bactria]]n [[Greeks]]; indeed the [[Mauryan]] subjection of this region was maybe the result of the fact that [[Chandragupta Maurya]] started his political career there and the irruptions of [[Alexander the Great|Alexander]] and [[Seleucus I Nicator|Seleucus]] had rendered its objectification in the conglomerate necessary. In the early mediaeval period also, the [[Rajput]] autocrats of the [[Ganga]] receptacle generally communicated interest in the politics of the [[Indus Valley]] states only when they were themselves hovered by the raiders coming from that direction. [[Prithviraja III]], the [[Chahamanas of Shakambhari]] king of [[Delhi]], for illustration, took no notice of the expansion of the [[Ghurid]] area in the [[Punjab]] till his own security was hovered and indeed after achieving palm in the [[First Battle of Tarain|first battle of Tarain]] he took no suitable way to oust the [[Muslims]] from the [[Punjab]]; he was putatively more interested in the politics of the antarvedi.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=278-280}} | |||

In the light of the below discussion, the station of the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] towards the [[Indus Valley]] becomes comprehensible, | |||

== Chandragupta II's Expeditions == | |||

=== Battle of Begram === | |||

[[File:Kushanshas-Hepthalites 565ad.jpg|thumb|The Kushano-Hephthalites & the Kushanshas in 565 AD.]] | |||

References to Kāpiši wine persist in literary works like Dhanapala's Tilakamanjari, describing it as a favored royal beverage with a reddish hue akin to a woman's eyes filled with resentment or the petals of a red lotus. Archaeological findings at [[Begram]] reveal ceramic motifs illustrating wine production, featuring jars, vines, grape bunches, and birds, reminiscent of Pompeii's artistry. Additionally, plaster medallions depict symmetrical arches formed by grape leaves and bunches, indicating Begram's historical significance as a grape-growing hub and wine production center.{{sfn|Prakash|1962|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=BqI5AQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y]337-338}} | |||

[[File:Kapisa in Afghanistan.svg|thumb|Kapisa in Afghanistan]] | |||

Recent archaeological endeavors uncovered a sizable wine cellar in [[Nisa, Turkmenistan|Nisa]], the former [[Parthian Empire|Parthian]] capital near modern-day [[Ashkabad]], containing nearly 200,000 liters of wine stored in clay pitchers. Inscriptions on broken pieces of pitchers suggest wine distribution to significant establishments like Nisa's prominent slave-owning palace and temple. The mention of grape wine in the [[Raghuvamsa]] underscores the poet's geographical awareness of [[Kapisi]]'s significance along land routes during Raghu's Persian campaign. After having crossed swords with the [[Yavanas]]. Raghu ([[Chandragupta II]]) fought a battle against the Parasikas ([[Persians]]) somewhere at the valley of Kāpiśi.{{sfn|Prakash|1962|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=BqI5AQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y]337-338}} | |||

=== Battle of Sistan and the Submission of Varahran === | |||

[[File:SakastanMap.jpg|thumb|left|Map of [[Sistan]] (labelled Sakastan) in c. 100 BC.]] | |||

[[File:Southeastern part of the Sasanian Empire.jpg|thumb|right|Map of [[Sakastan (Sasanian Province)|Sakastan]] under the [[Sasanians]].]] | |||

After the ([[Persians|Persian]]) [[Sasanians]] suffered defeat in the battle of [[Sistan]], which demorilzed the [[Persians|Persian]] contingents in present day [[Afghanistan]]. As the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] Army marched northwards to [[Kingdom of Kapisa|Kapisa Province]], Varahran was quick to grasp the political realities and offered his submission to the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] Emperor [[Chandragupta II]].{{sfn|Prakash|1962|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=BqI5AQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y]Chapter XIII and Chapter XIV}} | |||

=== Gupta cavalry's arrival by the Oxus river === | |||

[[File:ChandraguptaIIOnHorse.jpg|thumb|left|An 8 gram gold coin featuring [[Chandragupta II]] astride a caparisoned horse with a bow in his left hand. The name Cha-gu-pta appears in the upper left quadrant.<ref>*{{British-Museum-db|1910,0403.26|C_1910-0403-26}}</ref>]] | |||

[[Bactria]] was under the [[Huna people|Huna]] occupation in the last quarter of the fourth century AD.{{efn|"Taking [[Kalidasa|Kālidāsa]] to be a contemporary of [[Chandragupta II]], we can conclude that the [[Huna people|Hūṇas]] had occupied [[Bactria]] in the last quarter of the fourth century AD." {{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=hRjC5IaJ2zcC&vq=Oxus%23v%3Dsnippet&source=gbs_navlinks_s]240}}}} The sudden attack into the [[Oxus river|Oxus valley]] caught the [[Transoxiana]] alliance off-guard. The [[Pamir Mountains]] [[Tocharians]] were unable to combine with the [[Huna people|Hunas]] ([[Hephtalites]]). On hearing the news of the [[Gupta Empire]] advanced, the [[Hephtalites]] resorted to a tactical retreat to the north of the [[Oxus River]] into the plains of southern [[Uzbekistan]]. When the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] cavalry arrived by the [[Oxus river]] on the southern banks, they camped there. [[Kalidasa]] poetically described how the cavalry camped on the banks of the river [[Oxus|Vankshu]] in the midst of saffron fields in a verse of his [[Raghuvamsa]]: | |||

{{quote|"...His horses, that had lessened their fatigues of the road by turning from side to side on the banks of the river Vankshu ([[Oxus]]), shook their shoulders to which were clung the filaments of saffron..."}} | |||

[[File:Aral Sea watershed.png|thumb|Map showing the location of the [[Aral Sea]] and the watersheds of the [[Amu Darya]] (orange) and [[Syr Darya]] (yellow) which flow into the lake. National capitals in bold.]] | |||

Historians studied this as a description of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] cavalry camping on the banks of the [[Oxus]] during [[Chandragupta II]]'s expedition.<ref>{{Cite web |title=The Raghuvamsa Of Kalidasa. With The Commentary Of Mallinatha by Nandargikar, Gopal Raghunath: used/Good rebound full cloth (1982) {{!}} Prabhu Book Exports |url=https://www.abebooks.co.uk/Raghuvamsa-Kalidasa-Commentary-Mallinatha-Nandargikar-Gopal/30959799154/bd |access-date=22 March 2024 |website=www.abebooks.co.uk |language=en-GB|page=verse 66, Chapter XIII}}</ref>{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=hRjC5IaJ2zcC&q=Oxus&redir_esc=y#v=snippet&q=Oxus&f=false]166}} | |||

=== Kidara's conquest of Gandhara 356 CE and the Battle of the Oxus 399 CE === | |||

{{multiple image | |||

| align = right | |||

| direction =vertical | |||

| header="Kushan" coins of Kidara | |||

| total_width=230 | |||

| image1 = HUNNIC TRIBES Kidarites Kidara Circa CE 350-385.jpg | |||

| caption1 = {{Center|[[Kidara]] gold coin, circa 350–385 CE, derived from the [[Kushans]]. Vertical [[Brahmi]] legends from right to left:<br />''Kushana'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|14px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|14px]] ''Ku-shā-ṇa'')<br />''Kidara'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ki.jpg|16px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad d.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka r.svg|14px]] ''Ki-da-ra'')<br />''Kushana'' ([[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|14px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|14px]] ''Ku-shā-ṇa'')<br />Goddess [[Ardoxsho]] on the back.}} | |||

| image2 = Kushana in Brahmi script (diagonal).jpg | |||

| caption2 = {{Center|The word "Kushana" in [[Brahmi script]] ([[File:Gupta allahabad ku.jpg|14px]] [[File:Gupta gujarat ss.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka nn.svg|14px]] ''Ku-shā-ṇa'') as it appeared on the bottom left corner of Kidarite coins circa 350 CE.<ref>{{cite journal |last1=Tandon |first1=Pankaj |title=An Important New Copper Coin of Gadahara |journal=Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society |date=2009 |issue=200 |page=19 |url=https://www.academia.edu/2771790 |language=en}}</ref>}} | |||

| footer= | |||

}} | |||

'''Kidara I''' (Late [[Brahmi script]]: [[File:Gupta allahabad ki.jpg|16px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad d.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka r.svg|14px]] ''Ki-da-ra''; [[Floruit|fl.]] 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the [[Kidarite Kingdom]], which replaced the [[Indo-Sasanians]] in northwestern [[India]], in the areas of [[Kushanshahr]], [[Gandhara]], [[Kashmir]] and [[Punjab]].<ref name="HCCE 38">History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, [[Unesco]] [https://books.google.com/books?id=883OZBe2sMYC&pg=PA38 p.38 sq]</ref> | |||

However, Altekar suggests that [[Chandragupta II|Candragupta II]] attacked the [[Kidarites|Kidara Kushans]]. But in the situation also prevailing it isn't insolvable that [[Chandragupta II|Chandragupta]] really raided [[Balkh]] or [[Bactria]] appertained to as [[Bahlikas]] in the inscription. We already saw that [[Bactria]] was enthralled by the [[Hepthalites]] in about 350 A.D. ([[Kalidasa]] refers to the [[Hunas]] on the [[Oxus]]) and therefore had led to the eventual subjection of [[Gandhara]] by [[Kidara I|Kidara]] by 356 A.D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of [[Samudragupta]]). After [[Kidara I|Kidara]], his successors were known as little [[Yuechi|Yue-chi]]. As we have seen [[Samudragupta]] was satisfied with the offer of submission of [[Kidara I|Kidara]], and he also claims to have entered the submission of Shāhānushāhī (the [[Sasanian]] emperor), substantially to consolidate his vanquishing in the country, and to have some share and control over the renowned [[Silk Road|Silk-route]].{{efn|"However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."{{sfn|Sinha|1974|p=[https://books.google.mu/books/about/Comprehensive_History_of_Bihar.html?id=2WlDAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y 50–51]}}}} | |||

[[File:Chandra on the Iron Pillar of Delhi.jpg|thumb|The name "Candra" ([[File:Gupta allahabad c.svg|10px]]<sub>[[File:Gupta allahabad ndr.jpg|14px]]</sub>) on the iron pillar of Delhi, thought to represent [[Chandragupta II]]. [[Gupta script]]: letter "Ca" [[File:Gupta allahabad c.svg|12px]], followed by the [[conjunct consonant]] "ndra" formed of the vertical combination of the three letters ''n'' [[File:Gupta allahabad n.svg|14px]] ''d'' [[File:Gupta allahabad d.svg|14px]] and ''r'' [[File:Gupta ashoka r.svg|14px]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Bandela |first1=Prasanna Rao |title=Coin Splendour: A Journey into the Past |date=2003 |publisher=Abhinav Publications |isbn=9788170174271 |page=11 |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_mUg2BBJr7kC&pg=PA11 |language=en}}</ref>{{sfn|Allen|1914|p=[https://archive.org/details/in.gov.ignca.47214/page/n166 24]}}]] | |||

The [[Hunas]] in [[Bactria]] were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both [[Iran]] and [[India]], and they might have tried to pursue [[Kidara I|Kidara]] or his successors in [[Gandhara]], and [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] refers to [[Hepthalite]] king trying to remove [[Buddha]]'s coliseum from [[Peshawar|Purushapur]]. This may indicate [[Huna people|Huna]] invasion in [[Gandhara]] some time before [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] concluded his peregrination in [[India]]. It is said that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the [[Hunas]], leaving his son Piro at [[Peshawar]]. It's possible that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] might have gained some help from the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor. It is thus possible that [[Chandragupta II]] led an adventure to [[Bactria]] through [[Gandhara]] against the [[Hunas]], and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of [[Sindhu]] and conquering [[Bahlikas|Bahlika]] in the [[Iron pillar of Delhi|Mehrauli Pillar Inscription]]. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. [[Chandragupta II]]'s [[Bactria]]n expedition also led to the battle of the [[Oxus]] with his [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor having planted the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] flag on the banks of the river of [[Oxus]].{{efn|"However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."{{sfn|Sinha|1974|p=[https://books.google.mu/books/about/Comprehensive_History_of_Bihar.html?id=2WlDAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y 50–51]}}}}{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=hRjC5IaJ2zcC&vq=Oxus&source=gbs_navlinks_s]240 & 264}} | |||

[[File:Inscription on Iron Pillar, Delhi.jpg|thumb|upright=1.27|The inscription of [[Chandragupta II]]]] | |||

== The Imperial crisis == | |||

=== Gupta interregnum === | |||

[[File:Silver Coin of Kumaragupta I.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Silver coin of the Gupta King [[Kumaragupta I]] (Coin of his Western territories, design derived from the [[Western Satraps]]). | |||

<br />''Obv'': Bust of king with crescents, with traces of corrupt Greek script.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_mUg2BBJr7kC&pg=PA112 |title=Coin splendour: a journey into the past |last=Prasanna Rao Bandela |publisher=Abhinav Publications |year=2003 |isbn=978-81-7017-427-1 |pages=112– |access-date=21 November 2011 |archive-date=29 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130529030958/http://books.google.com/books?id=_mUg2BBJr7kC&pg=PA112 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>"Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of [[Chandragupta II]] is to be seen in his rare silver coins which are more directly imitated from those of the [[Western Satraps]]... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the reverse, they substitute the Gupta type (a peacock) for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc...", p. cli</ref> | |||

<br />''Rev'': [[Garuda]] standing facing with spread wings. Brahmi legend: ''Parama-bhagavata [[rajadhiraja]] Sri Kumaragupta Mahendraditya''.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Virji |first1=krishnakumari J. |title=Ancient History Of Saurashtra |date=1952 |page=225 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.57287/page/n249/mode/2up}}</ref>]] | |||

One of the topmost problems, which the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]], had to face in those times of excited conditioning, was the problem of race. At that time there were several ambitious tycoons in the Homeric family. [[Skandagupta]] and Purugupta were two of them. also, there was Ghatotkachagupta presumably also a son of [[Kumaragupta I]]. According to the law of royal race, which the ancient [[India]]n autocrats generally followed, the eldest son of [[Kumaragupta I]] should have succeeded him. But so far, the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] had shown spare respect to this principle. It's also not clear whether they regarded the first son sired on the senior-most queen or the eldest son, indeed if he happed to be the son of an inferior queen, as the licit descendant . maybe they hadn't bothered themselves to evolve a specific rule on this point. As regards the [[Hindu]] law books, it's nowhere laid down that the son of the principal-queen alone should succeed to the throne. In the early days of the conglomerate the nomination by the ruling autonomous was the most important factor. [[Chandragupta I]] had nominated [[Samudragupta]] as his successor and the ultimate, in his turn, presumably expressed his preference for his young son [[Chandragupta II]], over and above the claim of [[Ramagupta]], the elder brother of [[Chandragupta II]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=266-267}} | |||

It is not beyond the realm of possibility that towards the close of his reign, [[Kumaragupta I]] also expressed his preference for his valliant son [[Skandagupta]], though the evidence on this point is rather inconclusive. In this connection the Apratigha type of coins of the former furnish veritably intriguing substantiation. On the obverse of these issues we have three numbers. The central bone is really [[Kumaragupta I]] since he is expressly labelled as similar. He is shown wearing a dhoti. His hands are folded at midriff and he wears no jewelry on his person. He is adjoined on his right by a woman with her right hand bent up and raised in the station of ritarka (argumentation) and on his left by a joker, his left hand holding a guard and the right in the vitarka mudrā. According to Altekar, in this scene the emperor [[Kumaragupta I]] is shown as meaning repudiation and his queen and crown-prince are trying to inhibit him without success. The suggestion is relatively intriguing, though it is good to note that as these coins were issued during the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]] himself, he supposedly had not renounced his Homeric status altogether. To us it appears that in the ending times of his reign, [[Kumaragupta I]] entrusted the government of the conglomerate in the hands of his crown-prince and himself retired to lead a life of religious pursuits. Maybe commodity like this was behind the tradition recorded in the Kathasaritsagara according to which Mahendrāditya, generally linked with [[Kumaragupta I]], nominated his son Vikramaditya who had succeeded in inflicting a crushing defeat on the [[Mlecchas|Mlechchhas]] as his successor and himself retired to [[Varanasi]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=266-267}} | |||

According to the [[Buddhist]] work Chandragarbbapaṛiprichchhā also, the king Mahendrasena, identified with [[Kumaragupta I]] by K.P. Jayaswal, culminated his son Duprasahahasta, the whipper of the [[Yavanas]], Palhikas and Sakunas as his successor and himself retired to lead religious life. therefore, from the combined evidence of the Apratigha type of coins and the erudite tradition it appears that in his old age [[Kumaragupta I]] came virtually a isolate and the responsibility of administering his vast conglomerate regressed upon the shoulders of one of his sons. The prince who was named for this favour was supposedly no other than [[Skandagupta]], for, the Kathisarilsigara refers to him by the name of Vikramaditya, one of the titles espoused by [[Skandagupta]], and gives him the credit of conquering the [[Mlechchhas]], an achievement for which Skandagupta was regarded as the unique hero of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta dynasty]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=267-270}} | |||

[[File:KumaraguptaFightingLion.jpg|thumb|Kumaragupta I fighting a lion, as depicted on his gold coin<ref>CNG Coin [https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=65341]</ref>]] | |||

Numerous scholars, still believe that [[Skandagupta]] had no licit right to the throne and [[Kumaragupta I]], indeed if he'd all his affections reserved for the former couldn't give his throne to him. But the arguments cited in support of this proposition aren't conclusive. The view that the expression talpādānadhyāta was reflective of legal right to the throne and accordingly its elision in the Bhitari necrology for [[Skandagupta]] suggests that his claim was not licit, is not correct. The expression didn't have any indigenous significance. It was used indeed by the feudatory autocrats to express their fidelity towards their overlord. It is also relatively possible that as the author of the Bhitari record switched over from prose to verse at the place where the expression tatpādānadhyāta was to be used for [[Skandagupta]] to describe his devotion to his father, he gave its lyrical interpretation pitṛiparigatapādapadmavarti. P.L. Gupta remarks that this expression does not convey the sense that [[Skandagupta]] was the favourite of [[Kumaragupta I]]; it rather reflects his own anxiety to show that he was veritably important devoted to his father. But does not the expression tatpādānudhyāta also suggest the same idea–the devotion of the sovereign for which it was used for his precursor? It should also not be forgotten that in the Bhitari record the expression tatpādanadhyāta has been used neither for Ghatotkacha and nor for [[Chandragupta I]] and [[Samudragupta]]. Would it mean that none of these autocrats was the licit successor of his father? As regards the status of the mother of [[Skandagupta]], the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of the Bhitari record does not inescapably prove that she was not a Mahādevi. As refocused out by Raychaudhuri, the names of the maters of the lords were occasionally neglected in the ordinary pratastis, however in the royal seals they were always appertained indeed if it meant reiteration.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

In the genealogical portion of the [[Madhuban]] and Banskhera plates, the name of Yaśomati as Harsha's mother is not mentioned, but in the [[Sonepat]] and [[Nalanda]] seals she is mentioned both as the mother of [[Rajyavardhana]] and as the mother of [[Harshavardhan|Harsha]]. The view that the mother of [[Skandagupta]] was a doxy of [[Kumaragupta I]] and not a full-fledged queen, and that [[Skandagupta]] was ashamed of her status is altogether unwarranted. [[Skandagupta]] refers to her veritably proudly in the verse 6 of the Bhitari record. The change-over from prose to verse incontinently after the name of [[Kumaragupta I]], which redounded in the lyrical picture of the expression tatpādānadhyāta was maybe also the cause of the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of this record.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

Actually, so far as the struggle for the throne among the sons of [[Kumaragupta I]] is concerned, the question of the legality of [[Skandagupta]] is hardly applicable. For, indeed if he was not entitled to inherit the conglomerate, he could raise the banner of rebellion against the licit descendant and could win the preceding struggle. still, as yet there is nothing to show that his claim was less justified than that of other contenders. He was putatively devoted to and had the blessings of his father–a fact which is also suggested by the installation by him of an image of Sārngin in the memory of [[Kumaragupta I]]. It also needs no arguments to prove that he must have been the darling of the Homeric army. His consecutive military palms suggest it veritably explosively. But his rivals were not exactly helpless. Take, for illustration, Purugupta. In the Bhitari seal of Kumaragupta II he's described as begotten on the Mahadevi Anantadevi. Now, from the Bihar gravestone pillar necrology we learn that [[Kumaragupta I]] had married the family of his minister Anantasena. As in that period sisters were generally named after their sisters, it is nearly insolvable not to imagine that the queen Anantadevi was the family of Anantasena, the Homeric minister.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

However, it may be fluently conceded that Purugupta had an important section of ministers to support his candidature. If it was so. Then it may so be noted that after having consolidated his position as the new emperor, [[Skandagupta]] was obliged to appoint new 'pro-tectors' in all the businesses'. It may indicate that in some of the Homeric businesses his accession to the throne was opposed by the advanced officer-class. It is relatively possible that other contenders similar as Ghatotkachagupta, who had been the governor of the eastern [[Malwa]], reckoned substantially on similar original support. therefore, it appears that during the last times of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]] pulls from colorful directions sought to impact the question of race the emperor and the army favoured [[Skandagupta]], the queen Anantadevi and an important clerical party supported the cause of Purugupta and in some businesses original officers stoned the ambition of tycoons similar as Ghatotkachgupta. In such a condition, dominated by factional power- polities, a close contest for the throne was but ineluctable. Fortunately for the conglomerate, [[Skandagupta]], the unique hero of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta dynasty]], who had the blessings of his father and the support of the Homeric army on his side surfaced victorious in it. His rise gave a farther parcel of life to the conglomerate the palm of a weaker seeker would have quickened the pace of decomposition.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=273}} | |||

=== Pushyamitra invasion === | |||

[[File:Narmada river map.jpg|thumb|The [[Pushyamitras]] lived on the banks of the [[Narmada River]].]] | |||

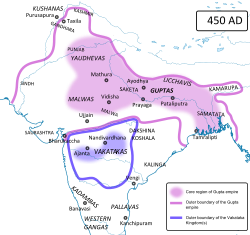

[[File:South Asia historical AD450 EN.svg|thumb|Political situation in [[India]] in 450 CE.]] | |||

Some of the troubles of [[Skandagupta]] were the result of the programs followed during the after times of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]]. As we have seen, [[Kumaragupta I]] had launched a vigorous crusade against his [[Vakataka]] relations eventually towards the concluding period of his reign which coincided with the early times of the reign of [[Narendrasena]] (c. 440-60 A.D.), the son and successor of [[Pravarasena II]]. In this adventure, the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] had an important inferior supporter in the [[Nala]] king Bhavattavarman. But from the [[Vakataka]] records, it appears that Narendrasena veritably soon succeeded in reacquiring the fallen fortunes of his family.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

In this attempt, he was mainly helped by his [[Kadamba dynasty]] relations; else one can not explain why Prithvishena II, the son of Narendrasena, should have mentioned his maternal forefather in the line of his family. therefore, in the middle of the fifth century A.D. two power-blocks-one conforming of the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] and the [[Nalas]] and the other comprising the [[Vakatakas]] and the [[Kadambas]] crystallized, and dominated the politics of the [[Deccan]]. Against this background the irruption of the [[Pushyamitras]], mentioned in the Bhitari record, assumes a new significance.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=273-274}} | |||

The identification and position of the home of the [[Pushyamitras]] of the Bhitari record have been largely controversial issues. But now it's generally honored that they belonged to the [[Mekala]] region. In the [[Vishnupurana]] MSS consulted by Wilson it's stated that the Pushpamitra (according to Wilson a variation of Pushyamitra), Patumitra and others, to the number of thirteen, will rule over [[Mekala]]. opining on this statement Wilson says" it seems most correct to separate the thirteen sons or families of the Vindhya queen( sic.) from these Bahlikas, and them from the Pushpamitras and Patumitras, who governed Mekala, a country on the Narmada.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

[[File:Mansar Shiva image.jpg|thumb|left|An image of [[Shiva]] from Mansar, currently housed in the [[National Museum, New Delhi]]. The image was likely produced during the reign of Pravarasena II, who was known to be a devout Shaivite.]] | |||

A statement of analogous import is set up in the [[Vaynpurana]] which is generally regarded as one of the oldest and the most dependable of Purana textbooks. It was on the base of this substantiation that Fleet and numerous others have located the [[Pushyamitras]] of the Bhitari record 'in [[central India]] nearly in the country along the banks of the [[Narmada]]'. Some scholars have expressed mistrustfulness about this suggestion, but the recent epigraphic discoveries haven't only given fresh support to his proposition but have also thrown a new light on the alignment of powers in this area. The most important of these documents is a bobby plate entitlement of the Pandavavarṁśi king [[Bharatabala]] alias Indra, discovered at [[Bamhani]] in [[Sohagpur]] tahsil of [[Rewa (princely state)|Rewa district]] in [[Baghelkhand]]. It records the entitlement of the village Vardhamanaka positioned in the Panchagarta Vishaya of Mekala to Lohita, a Brahmana of [[Vats (clan)|Vatsa gotra]]. Palaeographically, it has been credited to the middle of the fifth century A.D. by Chhabras and Mirashi. Accordingly, the origin of the [[Pandava]] family mentioned in it may be placed in the last quarter of the fourth century A.D.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

[[File:Nalanda clay seal of Vishnugupta.jpg|thumb|Nalanda clay seal of Vishnugupta]] | |||

It is true that in this record Jayabala and Vatstāja, the first two members of the family, have no royal title prefixed to their names, but it was maybe due to the fact that their description occurs in verse; the coming two lords are described both in prose and verse. In any case, it appears certain that the early autocrats of this family were the feudatories of the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]]. It is relatively possible that during the re-organisation of [[Baghelkhand]], [[Samudragupta]] gave an arena of Jayabala, the first member of this family. But the situation changed during the reign of Bharatabala. He is said to have married Lokaprakāśā, the queen of [[Kosala|Kosalā]]. She was presumably the son of the Sura king Bhimsena I who, according to Mirashi, was the contemporary of Bharatabala.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

In the 11th verse of the [[Bahmani]] record, Bharatabala makes a veiled reference to a certain Narendra, who appears to have been his suzerain. Chhabra and Mirashi identify this Narendra with Narendrasena, the contemporary [[Vakataka]] sovereign . It is not at each insolvable, for, from the [[Balaghat]] plates of Prithvisheņa II(c. 460- 80A.D.), the son and successor of Narendrasena, we learn that the cominands of the ultimate were fete by the autocrats of [[Kosala]], Mekalā and Malavā. therefore, the combined evidence of the Bamhani and the Balaghat plates prove it nearly conclusively that eventually in the middle of the fifth centuryA.D. the sovereign of Mekala transferred his constancy from the Guptas to the Vakatakas. From what we know about the history of the contemporary period, it's insolvable not to suggest that it must have happed either towards the close of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I|Kumāragupta I]] or in the carly times of the reign of [[Skandagupta]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

It appears that as a response against the aggressive policy of the Guptas, which led to the occupation of the Vakataka capital Nandivardhana by Bhavattavarman, the Nala supporter of the Guptas, the Vakataka sovereign Narendrasena, soon after recovering the lost ground, launched an descent against the Guptas when their conglomerate was passing through a period of grave extremity. The [[Pandava]] sovereign Bharatabala of Mekalā readily transferred his constancy to him. Studied against this background, the statement of the Bhitari record that Skandagupta conquered "the Pushyamitras, who had developed great power and wealth, (and) he placed (his) left foot on a foot-stool which was the king (of that lineage himself)" becomes significant. It's impeccably in consonance with what we know of the history of the [[Mekala]] region to which the [[Pushyamitras]] belonged. supposedly, [[Pushyamitras]] king of the Bhitari record was no other than the Pandava sovereign of Mekala, the inferior supporter of Narendrasena Vakataka and his irruption on the Gupta conglomerate, obviously with the help of the Vakataka sovereign , was a part of the general descent which Narendrasena had launched against the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

=== The Second Huna invasion === | |||

During Skandagupta's period, the [[Indo-Hephthalites]] (known as the White Huns or [[Huna people|Hunas]]) invaded [[India]] from the northwest, advancing as far as the [[Indus River]].{{sfn|R. C. Majumdar|1981|p=73}} | |||

[[File:Kakandi Script.jpg|thumb|Madra inscription on the [[Kahaum pillar]]]] | |||

==== Battle of the Indus river (458 A.D.) ==== | |||

During the Hun invasion, a battle along the [[Indus river]] took place which resulted in [[Skandagupta]] checking the advances of the Huns with them facing heavy losses.{{sfn|Fisher|Yarshater|1968|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Ko_RafMSGLkC]214}}{{sfn|Jaques|2007|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=ss5drgEACAAJ] 471}}{{efn|"In their second attempt, which took place in the initial years of the reign of [[Skandagupta]], these barbarians shook the foundation of the empire, though somehow [[Skandagupta]] ultimately succeeded in checking the tide of their progress."{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=280–281}}}} | |||

{{multiple image|border=infobox|perrow=2/2/2|total_width=300 | |||

| align = right | |||

| direction =horizontal | |||

| header=Bhitari pillar of Skandagupta | |||

| image1 = Bhitari pillar of Skandagupta.jpg | |||

| image2 = Bhitari pillar.jpg | |||

| footer=The Bhitari pillar of [[Skandagupta]] | |||

}} | |||

The Bhitari pillar inscription states that [[Skandagupta]] defeated the [[Hunas]]:{{sfn|R. C. Majumdar|1981|p=73}} | |||

{{quote|([[Skandagupta]]), "by whose two arms the earth was shaken, when he, the creator (of a disturbance like that) of a terrible whirlpool, joined in close conflict with the [[Huna people|Hûnas]]; . . . . . . among enemies | |||

== The Huna Volkerwanderung == | |||

The term '''post-Indic Völkerwanderung''' was first coined by an English historian [[Arnold J. Toynbee]] in the context when [[Gupta Empire]] was quivered to its roots. Considering that their earlier invasions had been repulsed by [[Chandragupta II]] and [[Skandagupta]] but the continuous incursions weakened the empire and trembled its internal affairs so well that they reduced them to a mere vassalage of the [[Hunas]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=336-337}} | |||

[[File:Greco-BactrianKingdomMap.jpg|thumb|Map of the [[Greco-Bactrian Kingdom]] at its maximum extent, circa 180 BC.]] | |||

[[File:Map of the Shungas.png|thumb|left|Extent of the [[Shunga Empire|Shungas]] after repulsing the [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] invasions {{Circa|150 BCE}}.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Schwartzberg |first1=Joseph E. |title=A Historical atlas of South Asia |date=1978 |publisher=University of Chicago Press |location=Chicago |page=145, map XIV.1 (c) |isbn=0-226-74221-0 |url=https://dsal.uchicago.edu/reference/schwartzberg/pager.html?object=182}}</ref>]] | |||

If we look to the archaic and mediaeval periods of [[India]]n history, the greatest compulsion to which the empires of the [[Ganga]] Valley were openly faced, came from the North-Western gates of [[Indian subcontinent]]. As indicated, the [[Indus basin]] was an area of great allurement for the Central and Western Asiatic hordes, who never missed any opportunity to exploit the weakened [[Gangetic]] empires. For instance, the fall of the [[Maurya Empire]] was associated with the successive invasions into the hinterland of the empire made by [[Bactrians]], and the [[Indo-Greeks]]. Although some [[gangetic]] empires endeavoured to impede these foreign aggression, For example, The [[Shungas]] halted the [[Indo-Greek Kingdom|Indo Greek]] invasions but they could not retain the old glory of [[Chandragupta Maurya]], which further resulted in a successive foreign invasions by [[Sakas]], [[Kushan Empire|Kushan]] and [[Huns|Hunnic]] hordes.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=336-341}} | |||

The onslaught of the [[Hunas]] adhered the uniform geographical pattern which had been abided by the [[Indo-Greeks]] in the post-[[Maurya]] era and was to be adhered to by the [[Turkic peoples]] in the medieval dates. Like the [[Indo-Greeks]] and the [[Turkic peoples]], the [[Hunas]] first amalgamated their power in the [[Punjab]]. After the setback endured at the hands of [[Skandagupta]] they had afresh turned the spotlight on [[Persia]]. When they made incursions in 456 A. D. we find [[Yazdegerd II|Yazdegird II]] relentless brawl against them. After his death in 457 A. D., Phiroz became the emperor of the [[Sassanian empire]], but the [[Hephthalite]] king [[Akhshunwar]] thwarted him and coercive him to pay tribute. In 484 A. D. Phiroz ventured a campaign against the [[Hephthalites]], but was defeated and killed. | |||

{{Quote|"This success raised the power of the Huns to its greatest heights, and the end of the fifth century A. D., they ruled over an extensive empire with their ancestral capital at [[Balkh]]".|author=[[Vincent Arthur Smith]], an [[Ireland|Irish]] [[Indologist]]}} | |||

According to Chavannes it visible that in c. 500 A. D. the [[Huns|Hunnic]] empire was [[Tokharistan]], [[Kabulistan]] and [[Zabulistan]] region but no territories of [[India]] were properly amalgamated except [[Gandhara]] and [[Chitral]], which were the north-western fringes of the [[Indian subcontinent]]. | |||

As Sung-Yun tells us: | |||

{{Quote|"This is the country which the Ye-thas destroyed, and afterwards set up a Tch'e-le (a tegin, prince or the member of the royal family) to be the king over the country; since which event two generations have passed."|author=[[Song Yun|Sung-Yun]], A [[China|Chinese]] traveller in [[Gandhara|Gandhar]]}} | |||

It is evident by the statement of [[Song Yun|Sung-Yun]] that extended up to [[Gandhara|Gandhar]] at least two generations before his visit to [[Gandhara|Gandhar]] in c. 520 A.D. Though it's unknown under whom leadership that these [[hunas]] conquered [[Gandhara|Gandhar]] but according to S.R Goyal, it is likely to be Rāmāṇila who subjugated Gandhar whose successor was [[Toramana]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=336-341}} | |||

Later came [[Toramana]] who amalgamated [[Huns|hunnic]] hordes in [[Punjab]] and further extended [[Huns|hunnic]] power up to [[Punjab]]. After consolidating in [[Punjab]] he launched a successive expedition in the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] domains when the empire was trembled by the internal strife as many emperors were getting either murdered or sidelined by tributary states. For instance a [[Jain]] work composed in 778 CE tells us that: | |||

{{Quote|"[[Toramana|Toramāṇa]] (written as Torarāya in one manuscript), who enjoyed the sovereignty of the world or Uttarāpatha, lived at Pavvaiyā on the bank of Chandrabhāgā ([[Chenab]])"|author=Kuvalayamālā.}} | |||

Moreover, it tells that Harigupta who claimed to be a scion of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta family]] was the instructor of Toramāṇa. Devagupta, a pupul of Harigupta is said to have a Rājarishi (Royal sage), the copper coins of [[Ramnagar|Rasool Nagar]] and [[Panchala]] reaffirms the certainty of Harigupta.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=336-341}} | |||

Recent discoveries of the two seals of [[Toramana|Toramāṇa]] from Kaushambhi states that he reached at least up to Kaushambhi. S.R. Goyal agrees with this conjecture and is given a factual reasons for it, from the ancient periods of [[India]]n history the invaders from north-west were always swept down up to [[Ganga]] valley and considering that Toramāṇa could not march up to [[Malwa]] without consolidating Kaushambhi was not possible. As a result, it is feasible that most of the upper Ganga valley had been conquered by Toramāṇa before he advanced as far as [[Eran]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=336-341}} | |||

== First Hunnic War == | |||

=== Huna conquest of Malwa === | |||

The [[Huna people|Huna]] conquest of the [[Gupta Empire]] was facilitated by the administrative structure of the empire, particularly its feudal system, which enabled the [[Huna people|Huna]] king to gain the support of local chiefs. Notably, inscriptions found in [[Eran]] provide insight into this dynamic. One inscription, dating to [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] era 165 (484 AD), documents constructions undertaken by Maharaja Matrivshnu and his brother Dhanyavishnu during the reign of [[Budhagupta]]. Another inscription, following Matrivshnu's death, details the temple construction by Dhanyavishnu during the rule of [[Toramana]] Sahi Jauvla, indicating his allegiance shift to the [[Huna people|Huna]] invader. This transition likely occurred after 484 AD, within a generation of that date.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=341}} | |||

Additionally, an inscription from [[Eran]], dated [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] era 191 (510 AD), recounts a battle where King [[Bhanugupta]] fought against the [[Hunas]], resulting in the death of his general Goparaja. This engagement possibly aimed to halt [[Huna people|Huna]] incursions into eastern [[Malwa]] or expel them from the region. If the former, [[Toramana]]'s conquest of eastern [[Malwa]] could be dated to 510 AD, and if the latter, sometime prior to that year. While the exact date of [[Huna people|Huna]] occupation in the region remains uncertain, it is plausible that [[Toramana]] established his rule in [[Malwa]] around 510 AD, considering the [[Huna people|Huna]] incursions into [[India]] began after 500 AD, following their confinement to [[Gandhara]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=341-342}} | |||

=== Bhanugupta and Toramana === | |||

[[File:Male head, northern India, Kushan or Gupta period, 5th-6th century CE, terracotta, HAA.JPG|thumb|Male head, northern [[India]], 5th-6th century CE.]] | |||

[[Bhanugupta]] is known from a stone pillar inscription in [[Eran]], [[Malwa]]. The inscription was translated by [[John Faithfull Fleet]] in 1888, and then a second time in 1981, leading to different interpretations. | |||

==== Initial translation (J.F Fleet 1888) ==== | |||

According to the initial translation of the [[Eran]] inscription (by [[John Faithfull Fleet|John Faithful Fleet]] in 1888), Bhanugupta participated to a non-specific battle in 510 CE (Line 5).<ref>{{harvp|Fleet|1888|p=93}}</ref> | |||

{{quote| | |||

{{multiple image|perrow=2|total_width=300|caption_align=center | |||

| align = right | |||

| direction =horizontal | |||

| header=Eran pillar inscription of Goparaja | |||

| image1 = Eran pillar of Goparaja (detail).jpg | |||

| caption1 = Eran pillar of Goparaja | |||

| image2 = Eran pillar inscription of Goparaja.jpg | |||

| caption2 = [[Eran]] stone pillar inscription of Bhanugupta. | |||

| image3 = Bhanugupta Eran stone pillar inscription.jpg | |||

| caption3 = Rubbing of the inscription. | |||

| footer= | |||

}} | |||

* (Line 1) Ôm! In a century of years, increased by ninety-one; on the seventh lunar day of the dark fortnight of (the month) Srâvana; (or in figures) the year 100 (and) 90 (and) 1; (the month) Srâvana; the dark fortnight; the day 7: — | |||

* (Line 2)—(There was) a king, renowned under the name of .... râja, sprung from the ... laksha (?) lineage; and his son (was) that very valorous king (who was known) by the name (of) Mâdhava. | |||

* (Line 3)— His son was the illustrious Gôparâja, renowned for manliness; the daughter's son of the Sarabha king; who is (even) now (?) the ornament of (his) lineage. | |||

* (Line 5) — (There is) the glorious Bhanugupta, the bravest man on the earth, a mighty king, equal to Pârtha, exceedingly heroic; and, along with him, Gôparâja followed .......... (his) friends (and came) here. [And] having fought a very famous battle, he, [who was but little short of being equal to] the celestial [king (Indra)], (died and) went to heaven; and (his) devoted, attached, beloved, and beauteous wife, in close companionship, accompanied (him) onto the funeral pyre.|source=[[Eran]] inscription of Bhanugupta, 510 CE.{{sfn|Fleet|1888|p=93}}}} | |||

This translation was the basis for various conjectures about a possible encounter with [[Toramana]], the [[Alchon Huns]] ruler. It has been suggested that Bhanugupta was involved in an important battle of his time, and suffered important losses, possibly against the Hun invader [[Toramana]], whom he may or may not have defeated in 510.<ref>Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.220</ref><ref>Encyclopaedia of Indian Events & Dates by S. B. Bhattacherje p.A15</ref> Mookerji actually considers, in view of the inscription, that Bhanugupta was vanquished by Toramana at this 510 CE Eran battle, so that the western Gupta province of [[Malwa]] fell into the hands of the Hunas at that point.{{sfn|Mookerji|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false]120}} Toramana would then have made his [[Eran]] boar inscription, claiming control of the region.{{sfn|Mookerji|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false]120}} | |||

==== New translation (1981) ==== | |||

A new revised translation was published in 1981.<ref name="CII" /> Verses 3-4 are markedly differently translated, in that ruler Bhanugupta and his chieftain or noble Goparaja are said to have participated in a battle against the "Maittras" in 510 CE, thought to be the [[Maitraka]]s (the reading being without full certainty, but "as good as certain" according to the authors).<ref name="CII" /> This would eliminate the suggestion that Bhanugupta alluded to a battle with [[Toramana]] in his inscription. | |||

{{quote| | |||

[[File:South Asia historical AD590 EN.svg|thumb|upright=1.36|The [[Maitraka]]s ruled in the areas of [[Gujarat]] and Western India. According to the 1981 translation, they may have been the adversaries of Gupta ruler Bhanugupta.<ref name="CII" />]] | |||

*(Lines 1-2) Ōm ! When a century of years, increased by ninety-one, (had elapsed) on the seventh lunar day of the dark fortnight of (the month) [[Śrāvaṇa]], (or in figures) the year 100 (and) 90 (and) 1 (the month) Śrāvaṇa the dark fortnight; the (lunar) day 7;- | |||

*(Verse 1) (there was) a ruler, renowned as .... [[rāja]] sprung from the Śulakkha lineage; and his son (was) valorous by the name (of) Mādhava. | |||

*(Verse 2) His son was the illustrious Goparaja, renowned for manliness; the daughter’s son of the Sarabha king;1 who became the ornament of (his) family. | |||

*(Verses 3-4) (There is) the glorious Bhanugupta, a distinguished hero on earth, a mighty ruler, brave being equal to [[Pârtha]]. And along with him Goparaja, following (him) without fear, <u>having overtaken the [[Maitraka|Maittras]] and having fought a very big and famous battle</u>, went to heaven, becoming equal to [[Indra]], the best of the gods; and (his) devoted, attached, beloved, and beauteous wife, clinging (to him), entered into the mass of fire (funeral pyre). | |||

|[[Eran]] inscription of Bhanugupta, 510 CE.<ref name="CII">Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum Vol.3 (inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings) [https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.108395 Main text p.352sq]</ref>}} | |||

Bhanugupta in the inscription is only mentioned as a "Raja" and not a "Maharaja" or a "Maharajadhiraja" as would be customary for a Gupta Empire ruler. Therefore, he may only have been a Governor for the region of [[Malwa]], under Gupta Emperor [[Narasimhagupta]].{{sfn|Mookerji|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false]120}} | |||

=== Battle of Eran 510 CE, Sack of Kausambhi 497–500 CE and the Battle of Malwa 510 CE === | |||

A decisive battle occurred in [[Malwa]], where a local Gupta ruler, probably a governor, named [[Bhanugupta]] was in charge. In the ''[[Bhanugupta]] [[Eran]]'' inscription, this local ruler reports that his army participated in a great battle in 510 CE at [[Eran]], where it suffered severe casualties.{{sfn|Mookerji|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false]120}} Bhanugupta was probably vanquished by Toramana at this battle, so that the western Gupta province of [[Malwa]] fell into the hands of the Hunas.{{sfn|Mookerji|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false]120}} | |||

[[File:Toramana portrait from coin.jpg|thumb|left|upright=0.79|Portrait of [[Toramana]]. He sacked [[Kausambi]] and occupied [[Malwa]].<ref>{{cite journal |last1=ALRAM |first1=MICHAEL |title=Three Hunnic Bullae from Northwest India |journal=Bulletin of the Asia Institute |date=2003 |volume=17 |page=180, Figure 11 |jstor=24049314 |url=https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/24049314.pdf |issn=0890-4464}}</ref>]] | |||

According to a 6th-century CE Buddhist work, the ''[[Manjusri-mula-kalpa]]'', Bhanugupta lost Malwa to the "[[Shudra]]" [[Toramana]], who continued his conquest to [[Magadha]], forcing [[Narasimhagupta]] Baladitya to make a retreat to [[Bengal]]. Toramana "possessed of great prowess and armies" then conquered the city of [[Tirtha (Hinduism)|Tirtha]] in the [[Gauda Kingdom|Gauda]] country (modern [[Bengal]]).{{sfn|Thakur|1967|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=drQ9AAAAMAAJ&redir_esc=y]122}}<ref group="Note">"After the successful conclusion of the [[Eran]] episode, the conquering [[Hunas]] ultimately burst out of Eastern [[Malwa]] and swooped down upon the very heart of the Gupta empire. The eastern countries were overrun and the city of the Gaudas was occupied. The Manjusrimulakalpa gives a scintillating account of this phase of Toramana's conquest. It says that after [[Bhanugupta]]'s defeat and discomfiture, Toramana led the Hunas against Magadha and obliged Baladitya (Narasimha-gupta Baladitya, the reigning Gupta monarch) to retire to [[Bengal]]. This great monarch (Toramana), Sudra by caste and possessed of great prowess and armies took hold of that position (bank of the Ganges) and commanded the country round about. That powerful king then invested the town called Tirtha in the [[Gauda Kingdom|Gauda]] country." in {{cite book|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=drQ9AAAAMAAJ|title=The Hūṇas in India|author=Upendra Thakur|publisher=Chowkhamba Sanskrit Series Office|year=1967|volume=58|location=Varanasi|page=122|oclc=551489665}}</ref> Toramana is said to have crowned a new king in [[Benares]], named Prakataditya, who is also presented as a son of Narasimha Gupta.<ref name="Mookerji">{{cite book |author=Radhakumud Mookerji |title=The Gupta Empire |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=uYXDB2gIYbwC&pg=PA120 |edition=5th |year=1997 |publisher=Motilal Banarsidass |location=Delhi |isbn=978-81-208-0440-1 |page=120}}</ref> | |||

{{multiple image | |||

| align = right | |||

|direction=vertical | |||

| total_width =220 | |||

| image1 = Eran Boar.jpg | |||

| caption1 = The [[Eran]] "[[Varaha]]" boar, under the neck of which can be found the [[Eran boar inscription of Toramana|Eran boar inscription]] mentioning the rule of Toramana.<ref name="pro.geo.univie.ac.at">{{Cite web |url=http://pro.geo.univie.ac.at/projects/khm/showcases/showcase9?language=en |title=Coin Cabinet of the Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna |access-date=23 July 2017 |archive-date=1 November 2019 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20191101061621/http://pro.geo.univie.ac.at/projects/khm/showcases/showcase9?language=en |url-status=dead}}</ref> | |||

| image2=Maharajadhiraja Sri Toramana on Eran boar inscription.jpg | |||

| caption2={{center|[[File:Gupta allahabad m.svg|12px]] [[File:Gupta ashoka haa.jpg|16px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad raa.jpg|10px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad j.svg|13px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad dhi.jpg|11px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad raa.jpg|10px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad j.svg|14px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad shrii.jpg|12px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad to.jpg|12px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad r.svg|12px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad maa2.jpg|12px]] [[File:Gupta allahabad nn.svg|14px]]<br />''Mahārājadhirāja Shrī Toramāṇa''<br />"Great King of Kings, Lord Toramana"<br /> in the [[Eran boar inscription of Toramana]] in the [[Gupta script]].<ref>{{cite book |last1=Fleet |first1=John Faithfull |title=Inscriptions Of The Early Gupta Kings And Their Successors |date=1960 |pages=[https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.463254/page/n4 158]–161 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.463254}}</ref>}} | |||

| image3 = Toramana gold coin circa 490-515.jpg | |||

| caption3 = A rare gold coin of [[Toramana]] in the style of the Guptas. The obverse legend reads: "The lord of the Earth, Toramana, having conquered the Earth, wins Heaven".<ref name="CNG Coins">{{Cite web |url=https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=301345 |title=CNG: Feature Auction Triton XIX. HUNNIC TRIBES, Alchon Huns. Toramana. Circa 490-515. AV Dinar (18 mm, 9.53 g, 12h). |website=www.cngcoins.com |accessdate=2 April 2023}}</ref><ref name="coinindia.com">{{Cite web |url=http://coinindia.com/Prakasaditya.pdf |title=The Identity of Prakasaditya by Pankaj Tandon, Boston University |accessdate=2 April 2023}}</ref> | |||

}} | |||

Having conquered the territory of Malwa from the Guptas, Toramana was mentioned in a famous inscription in [[Eran]], confirming his rule on the region.<ref name="Mookerji" /> The ''[[Eran boar inscription of Toramana]]'' (in [[Eran]], Malwa, 540 km south of [[New Delhi]], state of [[Madhya Pradesh]]) of his first regnal year indicates that eastern [[Malwa]] was included in his dominion. The inscription is written under the neck of the boar, in 8 lines of [[Sanskrit]] in the [[Brahmi script]]. The first line of the inscription, in which Toramana is introduced as ''Mahararajadhidaja'' (The Great King of Kings),<ref name="Sinha1977" />{{rp|79}} reads: | |||

{{blockquote|In year one of the reign of the King of Kings Sri-[[Toramana]], who rules the world with splendor and radiance...|[[Eran boar inscription of Toramana]]<ref name="pro.geo.univie.ac.at" />}} | |||

On his gold coins minted in India in the style of the Gupta Emperors, Toramana presented himself confidently as: | |||

{{blockquote|''Avanipati Torama(no) vijitya vasudham divam jayati'' | |||

The lord of the Earth, Toramana, having conquered the Earth, wins Heaven | |||

|Toramana gold coin legend.<ref name="CNG Coins" /><ref name="coinindia.com" />}} | |||

The fact that the Alchon Huns issued gold coins, such as the Toramana issue, in addition to their silver and copper coins, suggest that their empire in India was quite rich and powerful.<ref>"This makes it quite clear that the Alchon Huns in India must have had a substantial and rich empire, with the capacity to issue a relatively large volume of gold coins." in {{cite journal |last1=TANDON |first1=PANKAJ |s2cid=43869990 |title=The Identity of Prakāśāditya |journal=Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society |date=7 July 2015 |volume=25 |issue=4 |page=668 |doi=10.1017/S1356186315000346 |hdl=2144/37851 |hdl-access=free}} [http://coinindia.com/Prakasaditya.pdf Full article]</ref> | |||

{{multiple image | |||

| align = right | |||

|direction=horizontal | |||

| total_width =400 | |||

| title=Kausambi | |||

| caption_align = center | |||

| image1 = Ghoshitaram monastery in Kosambi.jpg | |||

| caption1 =The monastery of Ghoshitarama in [[Kausambi]] was probably destroyed by the Alchon Huns under Toramana.{{sfn|Gupta|1989|pp=174–175}} | |||

| image2=Kosambi Huna Raja seal impression.jpg | |||

| caption2="''Hūna Rāja''" Toramana seal impression, Kausambi<ref>{{cite book |page=18 |title=Indian Archaeology 1954–55 A review |url=http://nmma.nic.in/nmma/nmma_doc/Indian%20Archaeology%20Review/Indian%20Archaeology%201954-55%20%20A%20Review.pdf}}</ref> | |||