White House

| White House | |

|---|---|

Top: the northern facade with a columned portico facing Lafayette Square Bottom: the southern facade with a semi-circular portico facing the South Lawn and The Ellipse | |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 526: Unable to find the specified location map definition: "Module:Location map/data/United States Washington, D.C. central" does not exist. | |

Top: the northern facade with a columned portico facing Lafayette Square Bottom: the southern facade with a semi-circular portico facing the South Lawn and The Ellipse | |

| General information | |

| Architectural style | Neoclassical, Palladian |

| Address | 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW Washington, D.C. 20500 U.S. |

| Coordinates | 38°53′52″N 77°02′11″W / 38.8977°N 77.0365°WCoordinates: 38°53′52″N 77°02′11″W / 38.8977°N 77.0365°W |

| Current tenants | Joe Biden, President of the United States and the First Family |

| Construction started | October 13, 1792 |

| Completed | November 1, 1800[1] |

| Technical details | |

| Floor area | 55,000 sq ft (5,100 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | James Hoban |

| Website | |

| whitehouse | |

| Template:Infobox NRHP | |

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. The term "White House" is often used as a metonym for the president and their advisers.

The residence was designed by Irish-born architect James Hoban[2] in the neoclassical style. Hoban modelled the building on Leinster House in Dublin, a building which today houses the Oireachtas, the Irish legislature. Construction took place between 1792 and 1800 using Aquia Creek sandstone painted white. When Thomas Jefferson moved into the house in 1801, he (with architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe) added low colonnades on each wing that concealed stables and storage.[3] In 1814, during the War of 1812, the mansion was set ablaze by the British Army in the Burning of Washington, destroying the interior and charring much of the exterior. Reconstruction began almost immediately, and President James Monroe moved into the partially reconstructed Executive Residence in October 1817. Exterior construction continued with the addition of the semi-circular South portico in 1824 and the North portico in 1829.

Because of crowding within the executive mansion itself, President Theodore Roosevelt had all work offices relocated to the newly constructed West Wing in 1901. Eight years later in 1909, President William Howard Taft expanded the West Wing and created the first Oval Office, which was eventually moved as the section was expanded. In the main mansion, the third-floor attic was converted to living quarters in 1927 by augmenting the existing hip roof with long shed dormers. A newly constructed East Wing was used as a reception area for social events; Jefferson's colonnades connected the new wings. East Wing alterations were completed in 1946, creating additional office space. By 1948, the residence's load-bearing exterior walls and internal wood beams were found to be close to failure. Under Harry S. Truman, the interior rooms were completely dismantled and a new internal load-bearing steel frame constructed inside the walls. On the exterior, the Truman Balcony was added. Once the structural work was completed, the interior rooms were rebuilt.

The modern-day White House complex includes the Executive Residence, West Wing, East Wing, the Eisenhower Executive Office Building (the former State Department, which now houses offices for the president's staff and the vice president) and Blair House, a guest residence. The Executive Residence is made up of six stories: the Ground Floor, State Floor, Second Floor, and Third Floor, as well as a two-story basement. The property is a National Heritage Site owned by the National Park Service and is part of the President's Park. In 2007, it was ranked second[4] on the American Institute of Architects list of "America's Favorite Architecture".

Early history[edit]

1789–1800[edit]

Following his April 1789 inauguration, President George Washington occupied two private houses in New York City as the executive mansion. He lived at the first, known as the Franklin House and owned by Treasury Commissioner Samuel Osgood, at 3Template:NbsCherry Street through late February 1790.[5][6] The executive mansion moved to the larger quarters of the Alexander Macomb House at 39–41 Broadway[6] where he stayed, with his wife and a small staff until August 1790. In May 1790, New York began construction of a "proper" house for the presidential mansion, Government House.[7] Washington never used the mansion because it was not completed until after the national capital was moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in December 1790.[7]

The July 1790 Residence Act designated the capital be permanently located in the new Federal District, and temporarily in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for ten years while the permanent capital was built.[8] Philadelphia rented the mansion of the wealthy merchant Robert Morris at 190 High Street (now 524–30 Market Street) as the President's House, which Washington occupied from November 1790 to March 1797.[9] Since the house was too small to accommodate the thirty people who made up the presidential family, staff, and servants, Washington had it enlarged.[9]

President John Adams also occupied the High Street mansion from March 1797 to May 1800. On Saturday, November 1, 1800, he became the first president to occupy the White House.[10]

The President's House in Philadelphia was converted into the Union Hotel, and later used for stores, before being demolished in 1832.[9]

Philadelphia began construction of a much grander presidential mansion several blocks away in 1792. It was nearly completed by the time of Adam's 1797 inauguration. However, Adams declined to occupy it saying he did not have Congressional authorization to lease the building. It remained vacant until it was sold to the University of Pennsylvania in 1800.[11]

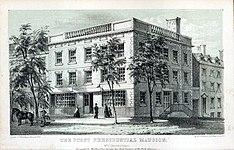

First Presidential Mansion: Samuel Osgood House, Manhattan, New York. Occupied by Washington: April 1789 – February 1790.

Second Presidential Mansion: Alexander Macomb House, Manhattan, New York. Occupied by Washington: February–August 1790.

Third Presidential Mansion: President's House, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Occupied by Washington: November 1790 – March 1797. Occupied by Adams: March 1797 – May 1800.

Government House, Manhattan, New York (1790–1791). Built to be the permanent presidential mansion, Congress moved the national capital to Philadelphia before its completion.

Architectural competition[edit]

The President's House was a major feature of Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant's[lower-alpha 1] 1791 plan for the newly established federal city, Washington, D.C.[12] Washington and his Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, who both had personal interests in architecture, agreed that the design of the White House, and the Capital, would be chosen in a design competition.[13]

Although all proposals for the Capital were rejected, an acceptable drawing for the White House submitted by James Hoban was selected from several including one submitted anonymously by Jefferson himself.[14]

Hoban was born in Ireland and trained at the Dublin Society of Arts. He emigrated to the US after the revolution, first seeking work in Philadelphia and later finding success in South Carolina where he designed several buildings including the state capitol at Columbia. Hoban ultimately supervised the construction of both the US Capitol and the White House.[15]

President Washington visited Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1791 on his "Southern Tour", and saw the under-construction Charleston County Courthouse designed by Hoban. He is reputed to have met with Hoban then. The following year, he summoned the architect to Philadelphia and met with him in June 1792.[16]

On July 16, 1792, the president met with the commissioners of the federal city to make his judgment in the architectural competition. His review is recorded as being brief, and he quickly selected Hoban's submission.[17]

Design influences[edit]

The building has classical inspiration sources, that can be found in the styles of the Roman architect Vitruvius and the Venetian architect Andrea Palladio; Palladio being an Italian architect of the Renaissance whose style evolved into Palladian architecture, which became popular in North American in the 18th century. Hoban's design is influenced by the upper floors of Leinster House, in Dublin, which later became the seat of the Oireachtas (the Irish parliament).[18] Several other Georgian-era Irish country houses have been suggested as sources of inspiration for the overall floor plan, details like the bow-fronted south front, and interior details like the former niches in the present Blue Room. These influences, though undocumented, are cited in the official White House guide, and in White House Historical Association publications. The first official White House guide, published in 1962, suggested a link between Hoban's design for the South Portico and Château de Rastignac, a neoclassical country house located in La Bachellerie in the Dordogne region of France and designed by Mathurin Salat. Construction on the French house was initially started before 1789, interrupted by the French Revolution for twenty years and then finally built 1812–1817 (based on Salat's pre-1789 design).[19] The theoretical link between the two houses has been criticized because Hoban did not visit France. Supporters of a connection posit that Thomas Jefferson, during his tour of Bordeaux in 1789, viewed Salat's architectural drawings (which were on-file at the college) at the École Spéciale d'Architecture (Bordeaux Architectural College).[20] On his return to the US he then shared the influence with Washington, Hoban, Monroe, and Benjamin Henry Latrobe.[19]

Construction[edit]

Though there is no record of a formal ceremony,[lower-alpha 2] construction of the White House began at noon on October 13, 1792, with the laying of the cornerstone.[22] The main residence, as well as foundations of the house, were built largely by enslaved and free African-American laborers, as well as employed Europeans.[23] Much of the other work on the house was performed by immigrants, many not yet with citizenship. The sandstone walls were erected by Scottish immigrants, employed by Hoban,[24] as were the high-relief rose and garland decorations above the north entrance and the "fish scale" pattern beneath the pediments of the window hoods. There are conflicting claims as to where the sandstone used in the construction of the White House originated. Some reports suggest sandstone from the Croatian island of Brač (specifically the Pučišća quarry whose stone was used to build the ancient Diocletian's Palace in Split) was used in the original construction of the building, contrarily researchers believe limestone from the island was used in the 1902 renovations and not the original construction. Others suggest the original sandstone simply came from Aquia Creek in Stafford County, Virginia, as importing the stone would be too costly.[25][26][27] The initial construction took place over a period of eight years, at a reported cost of $232,371.83 (equivalent to $Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN/calculation error, please notify Template talk:Inflation. in 2019). Although not yet completed, the White House was ready for occupancy circa November 1, 1800.[28]

Shortages of material and labor forced alterations to the earlier plan developed by French engineer Pierre Charles L'Enfant for a "palace" that was five times larger than the house that was eventually built.[24] The finished structure contained only two main floors instead of the planned three, and a less costly brick served as a lining for the stone façades. When construction was finished, the porous sandstone walls were whitewashed with a mixture of lime, rice glue, casein, and lead, giving the house its familiar color and name.[24]

Architectural description[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2020) |

The north front is the principal façade of the White House and consists of three floors and eleven bays. The ground floor is hidden by a raised carriage ramp and parapet, thus the façade appears to be of two floors. The central three bays are behind a prostyle portico (this was a later addition to the house, built circa 1830) serving, thanks to the carriage ramp, as a porte cochere. The windows of the four bays flanking the portico, at first-floor level, have alternating pointed and segmented pediments, while at second-floor level the pediments are flat. The principal entrance at the center of the portico is surmounted by a lunette fanlight. Above the entrance is a sculpted floral festoon. The roofline is hidden by a balustraded parapet.

The mansion's southern façade is a combination of the Palladian and neoclassical styles of architecture. It is of three floors, all visible. The ground floor is rusticated in the Palladian fashion. At the center of the façade is a neoclassical projecting bow of three bays. The bow is flanked by five bays, the windows of which, as on the north façade, have alternating segmented and pointed pediments at first-floor level. The bow has a ground floor double staircase leading to an Ionic colonnaded loggia (with the Truman Balcony at second-floor level), known as the south portico. The more modern third floor is hidden by a balustraded parapet and plays no part in the composition of the façade.

Naming conventions[edit]

The building was originally variously referred to as the "President's Palace", "Presidential Mansion", or "President's House".[29] The earliest evidence of the public calling it the "White House" was recorded in 1811.[30] A myth emerged that during the rebuilding of the structure after the Burning of Washington, white paint was applied to mask the burn damage it had suffered,[31] giving the building its namesake hue.[32] The name "Executive Mansion" was used in official contexts until President Theodore Roosevelt established the formal name by having "White House–Washington" engraved on the stationery in 1901.[33][34] The current letterhead wording and arrangement "The White House" with the word "Washington" centered beneath goes back to the administration of Franklin D. Roosevelt.[34]

Although the structure was not completed until some years after the presidency of George Washington, there is speculation that the name of the traditional residence of the president of the United States may have derived from Martha Washington's home, White House Plantation in Virginia, where the nation's first president had courted the first lady in the mid-18th century.[35]

Evolution of the White House[edit]

Early use, the 1814 fire, and rebuilding[edit]

On Saturday, November 1, 1800, John Adams became the first president to take residence in the building.[24] The next day he wrote his wife Abigail: "I pray Heaven to bestow the best of blessings on this House, and all that shall hereafter inhabit it. May none but honest and wise men ever rule under this roof."[36] President Franklin D. Roosevelt had Adams's blessing carved into the mantel in the State Dining Room.[36]

Adams lived in the house only briefly before Thomas Jefferson moved into the "pleasant country residence"[37] in 1801. Despite his complaints that the house was too big ("big enough for two emperors, one pope, and the grand lama in the bargain"),[38] Jefferson considered how the White House might be added to. With Benjamin Henry Latrobe, he helped lay out the design for the East and West Colonnades, small wings that help conceal the domestic operations of laundry, a stable and storage.[24] Today, Jefferson's colonnades link the residence with the East and West Wings.[24]

In 1814, during the War of 1812, the White House was set ablaze by British troops[39] during the Burning of Washington, in retaliation for attacking and burning Toronto (then called York),[40] Port Dover and other towns in Upper Canada; much of Washington was affected by these fires as well. Only the exterior walls remained, and they had to be torn down and mostly reconstructed because of weakening from the fire and subsequent exposure to the elements, except for portions of the south wall. Of the numerous objects taken from the White House when it was ransacked by British troops, only three have been recovered. Employees and slaves rescued a painting of George Washington,[39], in 1939, a Canadian man returned a jewelry box to President Franklin Roosevelt, claiming that his grandfather had taken it from Washington, and, also in 1939, a medicine chest that had belonged to President Madison was returned by the descendants of a British naval officer.[41][42] Some observers allege that most of these spoils were lost when a convoy of British ships led by HMS Fantome sank en route to Halifax off Prospect during a storm on the night of November 24, 1814,[43][44] even though Fantome had no involvement in that action.[45]

After the fire, President James Madison resided in the Octagon House from 1814 to 1815, and then the Seven Buildings from 1815 to the end of his term.[46] Meanwhile, both architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe and Hoban contributed to the design and oversight of the reconstruction, which lasted from 1815 until 1817. The south portico was constructed in 1824 during the James Monroe administration; the north portico was built six years later.[24] Though Latrobe proposed similar porticos before the fire in 1814, both porticos were built as designed by Hoban.[47] An elliptical portico at Château de Rastignac in La Bachellerie, France with nearly identical curved stairs is speculated as the source of inspiration due to its similarity with the South Portico,[48] although this matter is one of great debate.[49] Italian artisans, brought to Washington to help in constructing the U.S. Capitol, carved the decorative stonework on both porticos. Contrary to speculation, the North Portico was not modeled on a similar portico on another Dublin building, the Viceregal Lodge (now Áras an Uachtaráin, residence of the president of Ireland), for its portico postdates the White House porticos' design.[48] For the North Portico, a variation on the Ionic Order was devised incorporating a swag of roses between the volutes. This was done to link the new portico with the earlier carved roses above the entrance.

Jefferson and Latrobe's West Wing Colonnade, in this nineteenth-century engraved view, is now the James S. Brady Press Briefing Room.

Principal story plan for the White House by Benjamin Henry Latrobe, 1807

Earliest known photograph of the White House, taken c. 1846 by John Plumbe during the administration of James K. Polk

Overcrowding and building the West Wing[edit]

By the time of the American Civil War, the White House had become overcrowded. The location of the White House was questioned, just north of a canal and swampy lands, which provided conditions ripe for malaria and other unhealthy conditions.[50] Brigadier General Nathaniel Michler was tasked to propose solutions to address these concerns. He proposed abandoning the use of the White House as a residence and designed a new estate for the first family at Meridian Hill in Washington, D.C., but Congress rejected the plan.[50] Another site under consideration was Metropolis View, today the campus of The Catholic University of America.[51]

When Chester A. Arthur took office in 1881, he ordered renovations to the White House to take place as soon as the recently widowed Lucretia Garfield moved out. Arthur inspected the work almost nightly and made several suggestions. Louis Comfort Tiffany was asked to send selected designers to assist. Over twenty wagonloads of furniture and household items were removed from the building and sold at a public auction.[52] All that was saved were bust portraits of John Adams and Martin Van Buren.[53] A proposal was made to build a new residence south of the White House, but it failed to gain support.

In the fall of 1882 work was done on the main corridor, including tinting the walls pale olive and adding squares of gold leaf, and decorating the ceiling in gold and silver, and colorful traceries woven to spell "USA". The Red Room was painted a dull Pomeranian red, and its ceiling was decorated with gold, silver, and copper stars and stripes of red, white, and blue. A fifty-foot jeweled Tiffany glass screen, supported by imitation marble columns, replaced the glass doors that separated the main corridor from the north vestibule.[54][55]

In 1891, First Lady Caroline Harrison proposed major extensions to the White House, including a National Wing on the east for a historical art gallery, and a wing on the west for official functions.[50] A plan was devised by Colonel Theodore A. Bingham, which reflected the Harrison proposal.[50] These plans were ultimately rejected.

However, in 1902 Theodore Roosevelt hired McKim, Mead & White to carry out expansions and renovations in a neoclassical style suited to the building's architecture, removing the Tiffany screen and all Victorian additions.[56][57] Charles McKim himself designed and managed the project, which gave more living space to the president's large family by removing a staircase in the West Hall and moving executive office staff from the second floor of the residence into the new West Wing.[24]

President William Howard Taft enlisted the help of architect Nathan C. Wyeth to add additional space to the West Wing, which included the addition of the Oval Office.[50] In 1925, Congress enacted legislation allowing the White House to accept gifts of furniture and art for the first time.[58]:17 The West Wing was damaged by fire on Christmas Eve 1929; Herbert Hoover and his aides moved back into it on April 14, 1930.[59] In the 1930s, a second story was added, as well as a larger basement for White House staff, and President Franklin Roosevelt had the Oval Office moved to its present location: adjacent to the Rose Garden.[24]

Truman reconstruction[edit]

Decades of poor maintenance, the construction of a fourth story attic during the Coolidge administration, and the addition of a second-floor balcony over the south portico for Harry S. Truman[60] took a great toll on the brick and sandstone structure built around a timber frame.[24] By 1948, the house was declared to be in imminent danger of collapse, forcing President Truman to commission a reconstruction and to live across the street at Blair House from 1949 to 1951.[61] The work, done by the firm of Philadelphia contractor John McShain, required the complete dismantling of the interior spaces, construction of a new load-bearing internal steel frame and the reconstruction of the original rooms within the new structure.[60] The total cost of the renovations was about $5.7Template:Nbsmillion ($Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN/calculation error please notify Template talk:Inflation. million in 2019).[62] Some modifications to the floor plan were made, the largest being the repositioning of the grand staircase to open into the Entrance Hall, rather than the Cross Hall.[60] Central air conditioning was added, as well as two additional sub-basements providing space for workrooms, storage, and a bomb shelter.[24] The Trumans moved back into the White House on March 27, 1952.[24] While the house's structure was kept intact by the Truman reconstruction, much of the new interior finishes were generic, and of little historic value. Much of the original plasterwork, some dating back to the 1814–1816 rebuilding, was too damaged to reinstall, as was the original robust Beaux Arts paneling in the East Room. President Truman had the original timber frame sawn into paneling; the walls of the Vermeil Room, Library, China Room, and Map Room on the ground floor of the main residence were paneled in wood from the timbers.[63]

Jacqueline Kennedy restoration[edit]

Jacqueline Kennedy, wife of President John F. Kennedy (1961–63), directed a very extensive and historic redecoration of the house. She enlisted the help of Henry Francis du Pont of the Winterthur Museum to assist in collecting artifacts for the mansion, many of which had once been housed there.[64] Other antiques, fine paintings, and improvements of the Kennedy period were donated to the White House by wealthy philanthropists, including the Crowninshield family, Jane Engelhard, Jayne Wrightsman, and the Oppenheimer family.

Stéphane Boudin of the House of Jansen, a Paris interior-design firm that had been recognized worldwide, was employed by Jacqueline Kennedy to assist with the decoration.[64] Different periods of the early republic and world history were selected as a theme for each room: the Federal style for the Green Room, French Empire for the Blue Room, American Empire for the Red Room, Louis XVI for the Yellow Oval Room, and Victorian for the president's study, renamed the Treaty Room. Antique furniture was acquired, and decorative fabric and trim based on period documents was produced and installed. The Kennedy restoration resulted in a more authentic White House of grander stature, which recalled the French taste of Madison and Monroe.[64] In the Diplomatic Reception Room, Mrs. Kennedy installed an antique "Vue de l'Amérique Nord" wallpaper which Zuber & Cie had designed in 1834. The wallpaper had hung previously on the walls of another mansion until 1961 when that house was demolished for a grocery store. Just before the demolition, the wallpaper was salvaged and sold to the White House.

The first White House guidebook was produced under the direction of curator Lorraine Waxman Pearce with direct supervision from Mrs. Kennedy.[65] Sale of the guidebook helped finance the restoration.

Kennedy showed her restoration of the White House to the public in a televised tour of the house on Valentine's Day in 1962.[66]

The White House since the Kennedy restoration[edit]

Congress enacted legislation in September 1961 declaring the White House a museum. Furniture, fixtures, and decorative arts could now be declared either historic or of artistic interest by the president. This prevented them from being sold (as many objects in the executive mansion had been in the past 150 years). When not in use or display at the White House, these items were to be turned over to the Smithsonian Institution for preservation, study, storage, or exhibition. The White House retains the right to have these items returned.[58]:29

Out of respect for the historic character of the White House, no substantive architectural changes have been made to the house since the Truman renovation.[67] Since the Kennedy restoration, every presidential family has made some changes to the private quarters of the White House, but the Committee for the Preservation of the White House must approve any modifications to the State Rooms. Charged with maintaining the historical integrity of the White House, the congressionally-authorized committee works with each First Family – usually represented by the first lady, the White House curator, and the chief usher – to implement the family's proposals for altering the house.[68]

During the Nixon Administration (1969–1974), First Lady Pat Nixon refurbished the Green Room, Blue Room, and Red Room, working with Clement Conger, the curator appointed by President Richard Nixon.[69] Mrs. Nixon's efforts brought more than 600 artifacts to the house, the largest acquisition by any administration.[70] Her husband created the modern press briefing room over Franklin Roosevelt's old swimming pool.[71] Nixon also added a single-lane bowling alley to the White House basement.[72]

Computers and the first laser printer were added during the Carter administration, and the use of computer technology was expanded during the Reagan administration.[73] A Carter-era innovation, a set of solar water heating panels that were mounted on the roof of the White House, was removed during Reagan's presidency.[74][75] Redecorations were made to the private family quarters and maintenance was made to public areas during the Reagan years.[76] The house was accredited as a museum in 1988.[76]

In the 1990s, Bill and Hillary Clinton refurbished some rooms with the assistance of Arkansas decorator Kaki Hockersmith, including the Oval Office, the East Room, Blue Room, State Dining Room, Lincoln Bedroom, and Lincoln Sitting Room.[77] During the administration of George W. Bush, First Lady Laura Bush refurbished the Lincoln Bedroom in a style contemporary with the Lincoln era; the Green Room, Cabinet Room, and theater were also refurbished.[77]

The White House became one of the first wheelchair-accessible government buildings in Washington when modifications were made during the presidency of Franklin D. Roosevelt, who used a wheelchair because of his paralytic illness. In the 1990s, Hillary Clinton, at the suggestion of Visitors Office Director Melinda N. Bates, approved the addition of a ramp in the East Wing corridor. It allowed easy wheelchair access for the public tours and special events that enter through the secure entrance building on the east side.

In 2003, the Bush administration reinstalled solar thermal heaters.[75] These units are used to heat water for landscape maintenance personnel and for the presidential pool and spa. One hundred sixty-seven solar photovoltaic grid-tied panels were installed at the same time on the roof of the maintenance facility. The changes were not publicized as a White House spokeswoman said the changes were an internal matter. The story was picked up by industry trade journals.[78] In 2013, President Barack Obama had a set of solar panels installed on the roof of the White House, making it the first time solar power would be used for the president's living quarters.[79][80]

Layout and amenities[edit]

Today the group of buildings housing the presidency is known as the White House Complex. It includes the central Executive Residence flanked by the East Wing and West Wing. The Chief Usher coordinates day to day household operations. The White House includes six stories and 55,000 square feet (5,100 m2) of floor space, 132 rooms and 35 bathrooms, 412 doors, 147 windows, twenty-eight fireplaces, eight staircases, three elevators, five full-time chefs, a tennis court, a (single-lane) bowling alley, a movie theater (officially called the White House Family Theater[81]), a jogging track, a swimming pool, and a putting green.[34] It receives up to 30,000 visitors each week.[82]

Executive Residence[edit]

The original residence is in the center. Two colonnades – one on the east and one on the west – designed by Jefferson, now serve to connect the East and West Wings added later. The Executive Residence houses the president's dwelling, as well as rooms for ceremonies and official entertaining. The State Floor of the residence building includes the East Room, Green Room, Blue Room, Red Room, State Dining Room, Family Dining Room, Cross Hall, Entrance Hall, and Grand Staircase.[83] The Ground Floor is made up of the Diplomatic Reception Room, Map Room, China Room, Vermeil Room, Library, the main kitchen, and other offices.[84] The second floor family residence includes the Yellow Oval Room, East and West Sitting Halls, the White House Master Bedroom, President's Dining Room, the Treaty Room, Lincoln Bedroom and Queens' Bedroom, as well as two additional bedrooms, a smaller kitchen, and a private dressing room.[85] The third floor consists of the White House Solarium, Game Room, Linen Room, a Diet Kitchen, and another sitting room (previously used as President George W. Bush's workout room).[86]

West Wing[edit]

The West Wing houses the president's office (the Oval Office) and offices of his senior staff, with room for about 50 employees. It also includes the Cabinet Room, where the president conducts business meetings and where the Cabinet meets,[87] as well as the White House Situation Room, James S. Brady Press Briefing Room, and Roosevelt Room.[88] In 2007, work was completed on renovations of the press briefing room, adding fiber optic cables and LCD screens for the display of charts and graphs.[89] The makeover took 11 months and cost of $8Template:Nbsmillion, out of which news outlets paid $2Template:Nbsmillion.[89] In September 2010, a two-year project began on the West Wing, creating a multistory underground structure.[90]

Some members of the president's staff are located in the adjacent Eisenhower Executive Office Building, until 1999 called the Old Executive Office Building, and historically the State War and Navy building.[89]

The Oval Office, Roosevelt Room, and other portions of the West Wing were partially replicated on a sound stage and used as the setting for The West Wing television show.[91]

East Wing[edit]

The East Wing, which contains additional office space, was added to the White House in 1942. Among its uses, the East Wing has intermittently housed the offices and staff of the first lady, and the White House Social Office. Rosalynn Carter, in 1977, was the first to place her personal office in the East Wing and to formally call it the "Office of the First Lady". The East Wing was built during World War II in order to hide the construction of an underground bunker to be used in emergencies. The bunker has come to be known as the Presidential Emergency Operations Center.

Grounds[edit]

The White House and grounds cover just over 18 acres (about 7.3 hectares). Before the construction of the North Portico, most public events were entered from the South Lawn, the grading and planting of which was ordered by Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson also drafted a planting plan for the North Lawn that included large trees that would have mostly obscured the house from Pennsylvania Avenue. During the mid-to-late 19th century a series of ever larger greenhouses were built on the west side of the house, where the current West Wing is located. During this period, the North Lawn was planted with ornate carpet-style flowerbeds. The general layout of the White House grounds today is based on the 1935 design by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. of the Olmsted Brothers firm, commissioned by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. During the Kennedy administration, the White House Rose Garden was redesigned by Rachel Lambert Mellon. The Rose Garden borders the West Colonnade. Bordering the East Colonnade is the Jacqueline Kennedy Garden, which was begun by Jacqueline Kennedy but completed after her husband's assassination. On the weekend of June 23, 2006, a century-old American Elm (Ulmus americana L.) tree on the north side of the building came down during one of the many storms amid intense flooding. Among the oldest trees on the grounds are several magnolias (Magnolia grandiflora) planted by Andrew Jackson, including the Jackson Magnolia, reportedly grown from a sprout taken from the favorite tree of Jackson's recently deceased wife, the sprout planted after Jackson moved into the White House. The tree stood for over 200 years; but in 2017, having become too weak to stand on its own, it was decided it should be removed and replaced with one of its offspring.[92][93] Michelle Obama planted the White House's first organic garden and installed beehives on the South Lawn of the White House, which will supply organic produce and honey to the First Family and for state dinners and other official gatherings.[94] In 2020, First Lady Melania Trump redesigned the Rose Garden.

The Cross Hall, connecting the State Dining Room and the East Room on the State Floor

Marine One prepares to land on the South Lawn, where State Arrival Ceremonies are held.

Public access and security[edit]

Historical accessibility[edit]

Like the English and Irish country houses it was modeled on, the White House was, from the start, open to the public until the early part of the 20th century. President Thomas Jefferson held an open house for his second inaugural in 1805, and many of the people at his swearing-in ceremony at the Capitol followed him home, where he greeted them in the Blue Room. Those open houses sometimes became rowdy: in 1829, President Andrew Jackson had to leave for a hotel when roughly 20,000 citizens celebrated his inauguration inside the White House. His aides ultimately had to lure the mob outside with washtubs filled with a potent cocktail of orange juice and whiskey.[95] Even so, the practice continued until 1885, when newly elected Grover Cleveland arranged for a presidential review of the troops from a grandstand in front of the White House instead of the traditional open house. Inspired by Washington's open houses in New York and Philadelphia, John Adams began the tradition of the White House New Year's Reception.[96] Jefferson also permitted public tours of his house, which have continued ever since, except during wartime, and began the tradition of annual reception on the Fourth of July. Those receptions ended in the early 1930s, although President Bill Clinton briefly revived the New Year's Day open house in his first term.

Aviation incidents[edit]

This section needs to be updated. (April 2015) |

In February 1974, a stolen army helicopter landed without authorization on the White House's grounds.[97] Twenty years later, in 1994, a light plane flown by Frank Eugene Corder crashed on the White House grounds, and he died instantly.[98]

As a result of increased security regarding air traffic in the capital, the White House was evacuated in May 2005 before an unauthorized aircraft could approach the grounds.[99]

Closure of Pennsylvania Avenue[edit]

On May 20, 1995, primarily as a response to the Oklahoma City bombing of April 19, 1995, the United States Secret Service closed off Pennsylvania Avenue to vehicular traffic in front of the White House from the eastern edge of Lafayette Park to 17th Street. Later, the closure was extended an additional block to the east to 15th Street, and East Executive Avenue, a small street between the White House and the Treasury Building.

After September 11, 2001, this change was made permanent in addition to closing E Street between the South Portico of the White House and the Ellipse.[100] In response to the Boston Marathon bombing, the road was closed to the public in its entirety for a period of two days.

The Pennsylvania Avenue closing has been opposed by organized civic groups in Washington, D.C. They argue that the closing impedes traffic flow unnecessarily and is inconsistent with the well-conceived historic plan for the city. As for security considerations, they note that the White House is set much farther back from the street than numerous other sensitive federal buildings are.[101]

Prior to its inclusion within the fenced compound that now includes the Old Executive Office Building to the west and the Treasury Building to the east, this sidewalk[clarification needed] served as a queuing area for the daily public tours of the White House. These tours were suspended in the wake of the September 11 attacks. In September 2003, they resumed on a limited basis for groups making prior arrangements through their Congressional representatives or embassies in Washington for foreign nationals and submitting to background checks, but the White House remained closed to the public.[102] White House tours were suspended for most of 2013 due to budget constraints after sequestration.[103] The White House reopened to the public in November 2013.[104]

Protection[edit]

The White House Complex is protected by the United States Secret Service and the United States Park Police.

NASAMS (Norwegian Advanced Surface to Air Missile System) were used to guard air space over Washington, D.C. during the 2005 presidential inauguration. The same NASAMS units have since been used to protect the president and all airspace around the White House, which is strictly prohibited to aircraft.[105][106]

- PennAveWhiteHouse.jpg

For security reasons, the section of Pennsylvania Avenue on the north side of the White House is closed to all vehicular traffic, except government officials.

North front of the White House on the reverse (back) of the U.S. $20 bill.

See also[edit]

- Camp David

- Pedro Casanave

- Germantown White House

- Graphics and Calligraphy Office

- List of largest houses in the United States

- List of National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- List of residences of presidents of the United States

- Number One Observatory Circle, residence of the vice president

- Reported White House ghosts

- White House Acquisition Trust

- White House Chief Calligrapher

- White House Chief Floral Designer

- White House Christmas tree

- White House Communications Agency

- White House Endowment Trust

- White House Executive Chef

- White House Fellows

- White House History

- White House Social Secretary

- Category:Rooms in the White House

- White House COVID-19 outbreak

Notes[edit]

- ↑ L'Enfant identified himself as "Peter Charles L'Enfant" during most of his life while residing in the United States. He wrote this name on his "Plan of the city intended for the permanent seat of the government of t(he) United StatesTemplate:Nbs..." (Washington, D.C.) and on other legal documents. However, during the early 1900s, a French ambassador to the US, Jean Jules Jusserand, popularized the use of L'Enfant's birth name, "Pierre Charles L'Enfant". (Reference: Bowling, Kenneth R (2002). Peter Charles L'Enfant: vision, honor, and male friendship in the early American Republic. George Washington University, Washington, D.C. ISBN 978-0-9727611-0-9). The United States Code states in Template:USC: "(a) In General. – The purposes of this chapter shall be carried out in the District of Columbia as nearly as may be practicable in harmony with the plan of Peter Charles L'Enfant." The National Park Service identifies L'Enfant as "Major Peter Charles L'Enfant" and as "Major Pierre (Peter) Charles L'Enfant" on its website.

- ↑ Sources disagree[21]

References[edit]

- ↑ "John Adams moves into White House". History.com. Archived from the original on December 26, 2018. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Inside the White House: History". WhiteHouse.gov. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ↑ Michael W. Fazio and Patrick A. Snadon (2006). The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 364–366.

- ↑ to the Empire State Building

- ↑ Baker, William Spohn (1897). Washington After the Revolution: 1784–1799. p. 118. Retrieved January 15, 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Presidential Residency in New York". mountvernon.org. The Fred W. Smith Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon. Retrieved January 16, 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Stokes, Isaac Newton Phelps (1915–1928). The Iconography of Manhattan Island, 1498–1909. Robert H. Dodd.

- ↑ Miller, John (2003). Alexander Hamilton and the Growth of the New Nation. Transaction Publishers. p. 251. ISBN 0-7658-0551-0.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Edward Lawler, Jr. (May 2010). "A Brief History of the President's House in Philadelphia". ushistory.org. Archived from the original on February 20, 2012. Retrieved January 22, 2020.

- ↑ "John Adams". WhiteHouse.gov. Archived from the original on December 19, 2017. Retrieved January 22, 2015.

- ↑ Westcott, Thompson (1894). The Historic Mansions and Buildings of Philadelphia: With Some Notice of Their Owners and Occupants. W. H. Barr. pp. 270–272. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ↑ "Timelines-Architecture" (PDF). White House Historical Association. p. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 30, 2006. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ↑ Frary, Ihna Thayer (1940). They Built the Capital. Freeport, NY: Books for Library Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-8369-5089-2.

- ↑ Frary, Ihna Thayer (1969). They Built the Capitol. Ayer Publishing. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8369-5089-2.

- ↑ Frary, Ihna Thayer (1969). They Built the Capitol. Ayer Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-8369-5089-2.

- ↑ William Seale, "James Hoban: Builder of the White House" in White House History no. 22 (Spring 2008), pp. 8–12.

- ↑ "Primary Document Activities". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on November 9, 2007. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ↑ "The White House". National Park Service. Retrieved November 13, 2007.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Johnson, Michael (May 10, 2006). "Our White House in France?". TheColumnists.Com. Archived from the original on July 4, 2011. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael (September 15, 2006). "A chateau fit for a president". New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- ↑ "Building the White House". WHHA (en-US).

- ↑ Ecker, Grace Dunlop (1951) [1933]. "Chapter V: Washington and L'Enfant in George Town". In Grace G. D. Peter (ed.). A Portrait of Old George Town (Revised and Enlarged, 2nd ed.). Richmond, Virginia: The Dietz Press, Inc. p. 63. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ "African Americans in the White House Timeline". White House Historical Association. Retrieved March 21, 2016.

- ↑ 24.00 24.01 24.02 24.03 24.04 24.05 24.06 24.07 24.08 24.09 24.10 24.11 "White House Tour Essays: The Overview". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 28, 2007. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ Zentz, Wendy (November 9, 1986). "Yugoslavs Claim Bit Of White House". Sun Sentinel. Archived from the original on December 22, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ↑ Podolak, Janet (October 17, 2010). "Stone from island off Croatia made White House and ancient Roman palace". The News-Herald. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Croatia's Stone industry is expanding". www.litosonline.com. Retrieved February 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Overview of the White House". White House Museum. Archived from the original on November 11, 2015. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ Seale, William (1986). The President's House, A History. Volume I. White House Historical Association. pp. 1, 23. ISBN 978-0-912308-28-9.

- ↑ Seale, William (1992). The White House, The History of an American Idea. The American Institute of Architects Press. pp. 35. 1. ISBN 978-1-55835-049-6.

- ↑ Unger, Harlow (2009). The Last Founding Father:James Monroe and a Nation's Call to Greatness. New York: Da Capo Press. p. 277. ISBN 978-0-306-81808-0.

- ↑ New York Life Insurance Company (1908), entry

- ↑ Seale, William (1986). The President's House, A History. Volume II. White House Historical Association. p. 689.1. ISBN 978-0-912308-28-9.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "White House Facts". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on April 3, 2009. Retrieved February 24, 2017 – via National Archives.

- ↑ K.W. Poore and Associates, Inc.; Earth Design Associates, Inc. (June 2, 2002). "New Kent County Comprehensive Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2007. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 "The State Dining Room". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 2, 2006. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ↑ "Jefferson Describes the White House". Original Manuscripts and Primary Sources. Shapell Manuscript Foundation.

- ↑ John Whitcomb, Real Life at the White House: 200 Years of Daily Life at America's Most Famous Residence. Routledge, 2000. ISBN 978-0-415-92320-0. p. 15.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "The East Room". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 7, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ↑ Lafferty, Renee (July 13, 2015). "The Sacking of York". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- ↑ "reminders of 1814: president madison's medicine chest". whitehousehistory. The White House Historical Association. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

- ↑ "The Mariner's Mirror podcast (episode: the Battle of Trafalgar)". Mariner's Mirror. The Society for Nautical Research. Retrieved May 5, 2021.

....we have in the archive, a letter from Franklin Roosevelt, the American president, and it's thanking a descendant of one of Victory's crews, who are returning a medicine chest to the White House....this image of, of Roosevelt sitting down and writing a wonderful, and patient thank you letter, when he knows that the Germans have just invaded Czechoslovakia.....

- ↑ "Treasure hunt or modern-day pirates?". canada.com. 2006. Archived from the original on December 3, 2007. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ↑ Usborne, David (November 27, 2005). "British warship sunk during war with US may hold lost treasures of White House". The Independent. London. Retrieved January 28, 2011.

- ↑ Young, G.F.W. "HMS Fantome and the British Raid on Washington August 1814". Royal Nova Scotia Historical Society Journal. 10: 132–145.

- ↑ Haas, Irvin. Historic Homes of the American Presidents. New York: Dover Publishing, 1991, p. 30.

- ↑ Michael W. Fazio and Patrick A. Snadon (2006). The Domestic Architecture of Benjamin Henry Latrobe. The Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 368–370.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "Architectural Improvements: 1825–1872". The White House Museum. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ↑ Johnson, Michael (September 15, 2006). "A chateau fit for a president". International Herald Tribune. Archived from the original on March 14, 2007. Retrieved November 2, 2007.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 Epstein, Ellen Robinson (1971–1972). "The East and West Wings of the White House". Records of the Columbia Historical Society.

- ↑ Prudhomme, Claire (October 17, 2019). "Catholic University Could Have Been The White House". The Tower. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 268. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. pp. n473. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ↑ Reeves, Thomas C. (1975). Gentleman Boss. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 269. ISBN 978-0-394-46095-6.

- ↑ "The Grand Illumination: Sunset of the Gaslight Age, 1891". The White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on May 7, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ↑ "The Entrance Hall". The White House Museum. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ↑ "Theodore Roosevelt Renovation, 1902". The White House Museum. Archived from the original on April 25, 2015. Retrieved December 12, 2013.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Abbott, James A.; Rice, Elaine M. (1998). Designing Camelot: The Kennedy White House Restoration. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0-442-02532-7.

- ↑ Treese, Joel D.; Phifer, Evan (February 9, 2016). "The Christmas Eve West Wing Fire of 1929". The White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on October 31, 2018. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 "Truman Reconstruction: 1948–1952". White House Museum. Archived from the original on August 21, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ Slesin, Suzanne (June 16, 1988). "Fit for Dignitaries, Blair House Reopens Its Stately Doors". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Mrs. Truman Shows Off White House To News Writers". Palm Beach Post. UP. March 24, 1952. p. 7. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013. Retrieved March 29, 2012.

- ↑ "Library Art and Furnishings". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on June 23, 2010. Retrieved November 7, 2007 – via National Archives.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 "Kennedy Renovation: 1961–1963". White House Museum. Retrieved November 7, 2007.

- ↑ "Jacqueline Kennedy in the White House". John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum. p. 3. Archived from the original on March 3, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Jackie Kennedy's devotion to White House revealed". CBS News. February 14, 2012. Retrieved April 7, 2015.

- ↑ "Architecture: 1970s". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on January 1, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Executive Order 11145 – Providing for a Curator of the White House and establishing a Committee for the Preservation of the White House". The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. Archived from the original on January 8, 2011. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ Caroli, Betty Boyd (January 3, 2008). "Pat Nixon: American first lady". Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved January 21, 2017.

- ↑ "First Lady Biography: Pat Nixon". The National First Ladies Library. 2005. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

For the White House itself, and thus for the American people, Pat Nixon also decided to accelerate the collection process of fine antiques as well as historically associative pieces, adding some 600 paintings and antiques to the White House Collection. It was the single greatest collecting during any Administration.

- ↑ "A Press Pool". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on October 21, 2011. Retrieved September 18, 2017 – via National Archives.

- ↑ "Ask the White House". whitehouse.gov. May 9, 2005. Archived from the original on June 15, 2010. Retrieved December 7, 2008 – via National Archives.

- ↑ "Technology: 1980s". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on December 2, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Maine college to auction off former White House solar panels". October 28, 2004. Archived from the original on December 6, 2004. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 Burdick, Dave (January 27, 2009). "White House Solar Panels: What Ever Happened To Carter's Solar Thermal Water Heater?" (video). Huffington Post. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 "Decorative Arts: 1980s". White House Historical Association. Archived from the original on January 17, 2011. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Koncius, Jura (November 12, 2008). "White House makeover". The Californian. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved December 7, 2008.

- ↑ "Solar Energy is Back at the White House". www.ecomall.com.

- ↑ "Solar panels installed on White House roof". Fox News. August 15, 2013.

- ↑ Mary Bruce (August 15, 2013). "White House Finally Gets Solar Panels". ABC News.

- ↑ Johnson, Ted (July 23, 2011). "Now playing at the White House: East Wing holds movie theater for First Family and friends". Variety. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved November 19, 2012.

- ↑ Bumiller, Elizabeth (January 2009). "Inside the Presidency". National Geographic. Retrieved June 24, 2012.

- ↑ "White House Residence First Floor". White House Museum. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "White House Residence Ground Floor". White House Museum. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "White House Residence Second Floor". White House Museum. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "White House Residence Third Floor". White House Museum. Retrieved November 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Debates and Decisions: Life in the Cabinet Room". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved November 9, 2007 – via National Archives.

- ↑ "White House History and Tours". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on November 29, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2007 – via National Archives.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 89.2 Allen, Mike (July 7, 2007). "White House Press Room to reopen". Politico.

- ↑ "White House Big Dig wraps up, but the project remains shrouded in mystery". New York Daily News. Associated Press. September 13, 2012. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- ↑ "The West Wing of The West Wing". The White House Museum.

- ↑ "White House Magnolia Tree Planted by Andrew Jackson Will Be Cut Down". Smithsonian Magazine. December 28, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "The story of the White House's famous magnolia tree". The Washington Post. December 27, 2017. Retrieved December 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Michelle Obama Goes Organic and Brings in the Bees". Washington Whispers. March 28, 2009. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ↑ Greene, Elizabeth B. (2017). Buildings and Landmarks of 19th-Century America: American Society Revealed. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3573-5. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved May 24, 2020.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved January 14, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ Freeze, Christopher. "The Time a Stolen Helicopter Landed on the White House Lawn – Robert Preston's wild ride". Air & Space. Smithsonian. Archived from the original on March 23, 2017. Retrieved March 22, 2017.

- ↑ "White House security scares". BBC News. February 7, 2001.

- ↑ Johns, Joe; Arena, Kelli; Koch, Kathleen (May 12, 2005). "Intruding pilots released without charges". CNN. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Public Report of the White House Security Review". Order of the Secretary of the Treasury. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Statement of Committee of 100 on the Federal City and The National Coalition to Save Our Mall". National Coalition to Save Our Mall, Inc. 2004. Archived from the original on April 25, 2003. Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- ↑ "Visiting the White House". whitehouse.gov. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved November 8, 2007 – via National Archives.

- ↑ Hennessey, Kathleen (March 5, 2013). "White House tours canceled due to federal budget cuts". LA Times. Retrieved March 6, 2013.

- ↑ "White House Tours To Resume In November (With A Catch)". International Business Times. October 22, 2013. Retrieved April 19, 2014.

- ↑ "Norske våpen vokter presidenten". Gründer Økonomisk Rapport. January 31, 2006. Archived from the original on August 1, 2012. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

- ↑ "Norge sikret innsettelsen av Bush – Nyheter". Dagbladet. March 13, 2006. Retrieved August 15, 2010.

<ref> tag with name "nris" defined in <references> is not used in prior text.Further reading[edit]

- Abbott, James A. A Frenchman in Camelot: The Decoration of the Kennedy White House by Stéphane Boudin. Boscobel Restoration Inc.: 1995. ISBN 978-0-9646659-0-3.

- Abbott, James A. Jansen. Acanthus Press: 2006. ISBN 978-0-926494-33-6.

- Clinton, Hillary Rodham. An Invitation to the White House: At Home with History. Simon & Schuster: 2000. ISBN 978-0-684-85799-2.

- Garrett, Wendell. Our Changing White House. Northeastern University Press: 1995. ISBN 978-1-55553-222-2.

- Guidas, John. The White House: Resources for Research at the Library of Congress. Library of Congress, 1992.

- Huchet de Quénetain, Christophe. "De quelques bronzes dorés français conservés à la Maison-Blanche à Washington D.C." in La Revue, Pierre Bergé & associés, n°6, mars 2005 pp. 54–55. OCLC 62701407.

- Kenny, Peter M., Frances F. Bretter and Ulrich Leben. Honoré Lannuier Cabinetmaker from Paris: The Life and Work of French Ébiniste in Federal New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York and Harry Abrams: 1998. ISBN 978-0-87099-836-2.

- Klara, Robert. The Hidden White House: Harry Truman and the Reconstruction of America's Most Famous Residence. Thomas Dunne Books: 2013. ISBN 978-1-2500-0027-9.

- Kloss, William. Art in the White House: A Nation's Pride. White House Historical Association in cooperation with the National Geographic Society, 1992. ISBN 978-0-8109-3965-3.

- Leish, Kenneth. The White House. Newsweek Book Division: 1972. ISBN 978-0-88225-020-5.

- McKellar, Kenneth, Douglas W. Orr, Edward Martin, et al. Report of the Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion. Commission on the Renovation of the Executive Mansion, Government Printing Office: 1952.

- Monkman, Betty C. The White House: The Historic Furnishing & First Families. Abbeville Press: 2000. ISBN 978-0-7892-0624-4.

- New York Life Insurance Company. The Presidents from 1789 to 1908 and the History of the White House. New York Life Insurance Company: 1908.

- Penaud, Guy Dictionnaire des châteaux du Périgord. Editions Sud-Ouest: 1996. ISBN 978-2-87901-221-6.

- Phillips-Schrock, Patrick. The White House: An Illustrated Architectural History (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2013) 196 pp.

- Seale, William. The President's House. White House Historical Association and the National Geographic Society: 1986. ISBN 978-0-912308-28-9.

- Seale, William, The White House: The History of an American Idea. White House Historical Association: 1992, 2001. ISBN 978-0-912308-85-2.

- West, J.B. with Mary Lynn Kotz. Upstairs at the White House: My Life with the First Ladies. Coward, McCann & Geoghegan: 1973. ISBN 978-0-698-10546-1.

- Wolff, Perry. A Tour of the White House with Mrs. John F. Kennedy. Doubleday & Company: 1962. [ISBN missing]

- Exhibition Catalogue, Sale 6834: The Estate of Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis April 23–26, 1996. Sothebys, Inc.: 1996.

- The White House: An Historic Guide. White House Historical Association and the National Geographic Society: 2001. ISBN 978-0-912308-79-1.

- The White House. The First Two Hundred Years, ed. by Frank Freidel/William Pencak, Boston 1994. [ISBN missing]

External links[edit]

{{URL|example.com|optional display text}}- The White House Historical Association, with historical photos, online tours and exhibits, timelines, and facts

- President's Park (White House) part of the National Park Service

- The White House Museum, a detailed online tour

- Detailed 3D computer model of White House and grounds

- Video tours:

- "White House Holiday Tour with Laura Bush". C-SPAN. December 3, 2008.

- "White House Tour". C-SPAN. July 7, 1998.

- "Popular video tours". C-SPAN. Retrieved August 1, 2015.

- Template:Osmway

Template:White House Template:Washington DC landmarks Template:US POTUS Emergency Posts Template:National Register of Historic Places Template:Official Government residences in North America and the Caribbean

- White House

- 1800 establishments in Washington, D.C.

- Buildings and structures in the United States destroyed by arson

- Buildings of the United States government in Washington, D.C.

- Burned houses in the United States

- Federal architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Historic house museums in Washington, D.C.

- Houses completed in 1800

- Houses on the National Register of Historic Places in Washington, D.C.

- James Hoban buildings

- National Historic Landmarks in Washington, D.C.

- Neoclassical architecture in Washington, D.C.

- Northwest (Washington, D.C.)

- Presidential homes in the United States

- Presidential museums in Washington, D.C.

- Presidential residences in the United States

- Rebuilt buildings and structures in the United States

- Reportedly haunted locations in Washington, D.C.