Quit India speech

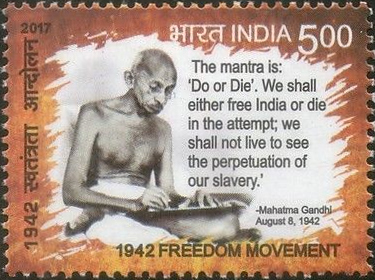

2017 postage stamp of India commemorating the Quit India Movement | |

| Date | August 8, 1942 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Gowalia Tank Maidan |

| Type | Speech |

| Target | British colonial government, Indian public |

| Organized by | Mahatma Gandhi |

The Quit India speech was given by Mahatma Gandhi on the eve of the Quit India movement, August 8, 1942. His address was issued shortly before midnight at the Gowalia Tank Maidan park in Bombay (present-day Mumbai),[1] which has since been renamed August Kranti Maidan (August Revolution Ground).

The speech was given in support of Indian independence and the end of British colonial rule. He called for determined, but passive resistance and civil disobedience based on the principles of satyagraha ("truthful request")[1] that signified the certitude that Gandhi foresaw for the movement, best described by his call to "Do or Die".

However, the movement did not end on a high note, since in less than twenty-four hours after giving his speech, Gandhi and almost the entire Indian National Congress leadership were imprisoned by the British colonial government under the grounds of the Defense of India Act.[2] A greater number of Congress leaders would spend the rest of the war in jail. The Quit India speech is commonly referred to as the unifying call to action in pursuit of Indian independence during WWII-wartime India.

Background[edit]

In August 1942, Indian politician and social activist, Mahatma Gandhi, was a central figure to the Quit India campaign.[3] He was the leader of the Indian National Congress,[4] and the Quit India campaign was a national protest movement based on "satyagraha" (truthful request)[1] that called for an end to British colonial rule in India and the establishment of Indian sovereignty[5] through nonviolent resistance and peaceful violation of laws.[1] The growth of the movement was largely driven by discontent with British colonial rule after the East India Company's territories in India was transferred to Crown control in 1858,[5] ultimately, culminating in a struggle between Indian independence activists and the British colonial authorities and leading to the Quit India Movement of 1942.

Having played a large role in the war effort, citizens across the country felt that they had the right to demand independence. The influence of the Indian experience of WWII had brought about the demand for the creation of a central, national Indian government, a demand that had elicited a popular nationwide response but which ultimately went ignored by the British colonial government.[6]

In support of the Indian independence movement, the political party Indian National Congress (INC), under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi , delivered "The Quit India Call" on August 8, 1942.[6] The speech, delivered in the midst of WWII, called for an end to British colonial rule as a means of ensuring the success of freedom and democracy[5] for India.

The Congress's initial response to the war, a policy of individual civil disobedience, developed into the larger Quit India Movement of 1942, characterized by wider civil disobedience that was suppressed by the government with "unforgiving repression".[7]

Gandhi's address, commonly referred to as the Quit India Speech, was made on the occasion of the main organizational wing of the INC's and the All India Congress Committee's (AICC) approval of the Quit India Resolution.[1] The resolution, approved in the concluding session of the AICC's meeting at Bombay,[5] authorized Gandhi to take whatever actions he deemed necessary to "force the British out of the country".[8]

Purpose[edit]

Following the unilateral decision of the British colonial government to bring India into World War II, the 1939 resignation of Congress ministries led to a chain of events that were responsible for Gandhi's speech and the beginning of the Quit India Movement,[1] a movement that expedited the Indian independence process.

Gandhi set out in his speeches to maintain the unification of India's diverse religious and ethnic groups. The increasing divide in the early 1940s between the separatist factions of the Hindu and Muslim majority populations meant that much of Gandhi's Quit India speech directly addressed their conflict and hostility.[1]

The ratification of the movement by Gandhi and the AICC on August 8, 1942 meant the adoption of the Quit India resolution and the ensuing Quit India satyagraha which followed.[9] Official Congress adoption of the Quit India Movement had to a considerable extent, worked to legitimize adherence to revolutionary and destructive actions which emphasized the role of youths and the core values of bravery, daring, and sacrifice.[5] Gandhi's mantra of “do or die” [10] as embodied in his speech, remain important tools for interpreting his vision of non-violence and satyagraha,[9] and its evolution alongside the pursuit of Indian independence.

Speech content and meaning[edit]

The Quit India speech was delivered in two languages, starting first in Hindi then followed by a shortened English version.[1] Through out the speech Gandhi affirms his commitment to non-violent protest and asserts that this movement would follow in the same fashion.[3]

The speech begins with Gandhi outlining his intentions to gain independence for India to the All India Congress Committee. He makes two especially crucial points in this part of the speech; a resolution based on “ahimsa”, an ancient Indian principle of non-violence, and expressing no hatred towards the British.[10] During the first part of the speech Gandhi reassured that their struggle was for India's independence not a fight for power. He proclaimed that “there had never been a more democratic struggle for freedom in world history than India's”.[7]

After the resolution was passed, Gandhi presented the second part of his speech. Addressed to many subgroups such as Muslim's and Hindu's. Gandhi outlines what the resolution asks of their participation in the movement.[10] Gandhi again preaches non-violence as his basic premise for the movement.[5]

The third part of the speech was presented in English, in which Gandhi directly addressed the Western world. This third portion of the speech clearly described how the resolution called for the independence of India from British colonial rule in such a way that Western audiences would be able to understand. This third section also stated that “this overthrow of British Rule would begin immediately.”.[10] It also provided an image of a unified India and provided a sketch of how the movement would play out. The English portion of the speech concluded with what would become the mantra of the entire Quit India Movement - “Do or Die.”.[10] This phrase came from an 1854 poem titled “Charge of the Light Brigade'', written by Alfred, Lord Tennyson to commemorate a failed military action during the Crimean War.[9] Gandhi had had a fascination with this phrase, using it several times in other addresses such as in 1904 to commemorate the actions of the British Indian Army in numerous conflicts they had fought over the “past several decades”, including the Younghusband expedition.[9] It then became the mantra of the Quit India Movement.

Audience[edit]

A wide variety of sources estimate there was between forty thousand and one hundred thousand people attending Gandhi's speech.[10] The first group that Gandhi was aiming his address to was the Muslim population of India.[1] Gandhi spoke to the Muslim population in his speech to inspire “a unity of hearts and a joint effort by Hindus and Muslims in the fight for freedom.”.[1] He believed that the freedom of India would benefit all Indians, and that religious differences should be put aside for the benefit of the movement.[1]

Another group that Gandhi addressed in his speech was the committee members who voted on the Quit India Resolution. Gandhi acknowledged all members for their commitment to the voting process and thanked them for participating, both those who voted for and against the resolution.[1]

Gandhi also spoke directly to other groups, such as “journalists, princes, landlords, soldiers, government officials, and students”.[1] He called on these groups to stand in solidarity through non-violent protest against British colonial rule. In opposition to previous speeches, Gandhi did not ask these groups to halt their work and classes but rather to continue, with the mentality and action of free subjects and social groups in passive resistance.[1]

Impacts[edit]

Gandhi's speech led to an immediate reaction from both the Indian public and the British colonial government. Following the Quit India speech, the citizens of India reacted in “mass upheaval of unprecedented dimensions.”.[6] The speech ultimately led to the passing of the Quit India Resolution by the All India Congress Committee, as well as the re-enactment of the non-violence and noncooperation policy.[5] The British colonial government, meanwhile, took the speech in a threatening manner and subsequently launched several major crackdowns on the Indian National Congress and its supporters.[6] Just hours after the speech, Gandhi and other prominent Indian nationalist leaders were arrested and imprisoned by the British, all of whom were eventually released.[1] Gandhi gave the speech to leave his colleagues with a message and with the hope that doing so may delay or stop his arrest entirely when he said, “After last night's speech they will never arrest me”.[8]

Following the speech, there was a significant uptick from the Indian public in support of the independence movement. There was a widespread belief among members of the public that India was finally going to gain its independence. This sentiment was misguided since the British would perceive it as a threat to their control.[1] Consequently this would lead to crackdowns from the colonial government, resulting in widespread violence from the Indian nationalists in response, despite Gandhi's non-violence policy. In the months that followed the speech, the country was wracked by pro-independence protests and violence. For 2 years, “208 police stations, 332 railway stations, and 945 post offices or telegraph lines were damaged or destroyed”.[1]

In particular, Gandhi's speech choices would impact various Indian subgroups: the switch from Hindustani to English was especially strategic in sending a message to a larger audience. The transition in language provides imagery of a united front as well as being able to inform the western world of their struggle for independence. The stark contrast in language within one speech brings focus to who Gandhi is addressing. It provided clarity to who he was addressing and invited a wide variety of groups to be his audience.[10] The inclusion of more than one language brings even more emphasis to Gandhi's philosophy of the Quit India Movement; the strongest India is a multicultural India.[10] Switching languages within the speech draws attention to the diversity within India and the “ethical values of different communities, especially those that have been impacted politically and are forced to speak multiple languages.”.[10]

Initial response and reception[edit]

Later on the evening of the Quit India Speech and the Congress's ratification of the Quit India Resolution, Gandhi and other Congress affiliates from top leaders to ordinary rank-and-file members were arrested and imprisoned by the government under the grounds of the Defense of India Act.[2] This act allowed the government the ability to carry out supposedly preventative detention, swelling the number of total arrests to some twenty thousand.[2] In addition, press coverage surrounding the speech was heavily limited. The publishing of any part of Gandhi's speech, the support of the Congress's call to action, and critiques of the British colonial government's actions were forbidden.[2]

Press reporting of the speech and Gandhi's last message did not pose any immediate danger to the British colonial government due to the swift ban on it.[11] The arrests of members of the AIWC and AICC also meant the distribution of both the speech and resolution to the public failed. Subsequently it meant that the colonial government's tactics had prevailed early on in controlling the Indian press and depriving Congress of its leadership, leaving the movement “directionless at its inception”.[11]

Legacy[edit]

Gandhi's mantra of “Do or Die" was ultimately successful due to the efforts of the underground press.[2] Through letters and fasting, imprisoned Gandhi was able to engage in a discourse with the Viceroy of India, also commonly referred to as the Governor-General of India, the monarch's official representative who retained complete authority over all of India.[2] This dialogue did not bring about Gandhi's release or lead any significant progress for the campaign. However reporting by the underground press made the Indian population aware that a discussion was indeed taking place, giving people some hope of settlement.[2] Acting as the unifying call to action for a campaign of civil disobedience, the Quit India movement spread far across the Indian subcontinent and had lasting effects from August 1942, the formal inception of the movement, until September 1944,[2] nearing the final stages of WWII.

Britain's response to the movement has been analyzed as one of the most significant parts of the Indian independence movement. The events of the Quit India Movement in 1942 had worked to persuade the British to leave India without establishing various measures of continued British control, measures which effectively acted as safeguards and which had “previously been demanded as a condition of withdrawal” [8] from the Indian subcontinent.

Before you discuss the resolution, let me place before you one or two things I want you to understand two things very clearly and to consider them from the same point of view from which I am placing them before you. I ask you to consider it from my point of view, because if you approve of it, you will be enjoined to carry out all I say. It will be a great responsibility. There are people who ask me whether I am the same man that I was in 1920, or whether there has been any change in me or you. You are right in asking that question.

Let me, however, hasten to assure that I am the same Gandhi as I was in 1920. I have not changed in any fundamental respect. I attach the same importance to non-violence that I did then. If at all, my emphasis on it has grown stronger. There is no real contradiction between the present resolution and my previous writings and utterances.

Occasions like the present do not occur in everybody's and rarely in anybody's life. I want you to know and feel that there is nothing but purest Ahimsa in all that I am saying and doing today. The draft resolution of the Working Committee is based on Ahimsa, the contemplated struggle similarly has its roots in Ahimsa. If, therefore, there is any among you who has lost faith in Ahimsa or is wearied of it, let him not vote for this resolution. Let me explain my position clearly. God has vouchsafed to me a priceless gift in the weapon of Ahimsa. I and my Ahimsa are on our trail today. If in the present crisis, when the earth is being scorched by the flames of Himsa and crying for deliverance, I failed to make use of the God given talent, God will not forgive me and I shall be judged unworthy of the great gift. I must act now. I may not hesitate and merely look on, when Russia and China are threatened.

Ours is not a drive for power, but purely a non-violent fight for India's independence. In a violent struggle, a successful general has been often known to effect a military coup and to set up a dictatorship. But under the Congress scheme of things, essentially non-violent as it is, there can be no room for dictatorship. A non-violent soldier of freedom will covet nothing for himself, he fights only for the freedom of his country. The Congress is unconcerned as to who will rule, when freedom is attained. The power, when it comes, will belong to the people of India, and it will be for them to decide to whom it placed in the entrusted. May be that the reins will be placed in the hands of the Parsis, for instance-as I would love to see happen-or they may be handed to some others whose names are not heard in the Congress today. It will not be for you then to object saying, “This community is microscopic. That party did not play its due part in the freedom's struggle; why should it have all the power?” Ever since its inception the Congress has kept itself meticulously free of the communal taint. It has thought always in terms of the whole nation and has acted accordingly. . . I know how imperfect our Ahimsa is and how far away we are still from the ideal, but in Ahimsa there is no final failure or defeat. I have faith, therefore, that if, in spite of our shortcomings, the big thing does happen, it will be because God wanted to help us by crowning with success our silent, unremitting Sadhana for the last twenty-two years.

I believe that in the history of the world, there has not been a more genuinely democratic struggle for freedom than ours. I read Carlyle's French Revolution while I was in prison, and Pandit Jawaharlal has told me something about the Russian revolution. But it is my conviction that inasmuch as these struggles were fought with the weapon of violence they failed to realize the democratic ideal. In the democracy which I have envisaged, a democracy established by non-violence, there will be equal freedom for all. Everybody will be his own master. It is to join a struggle for such democracy that I invite you today. Once you realize this you will forget the differences between the Hindus and Muslims, and think of yourselves as Indians only, engaged in the common struggle for independence.

Then, there is the question of your attitude towards the British. I have noticed that there is hatred towards the British among the people. The people say they are disgusted with their behaviour. The people make no distinction between British imperialism and the British people. To them, the two are one. This hatred would even make them welcome the Japanese. It is most dangerous. It means that they will exchange one slavery for another. We must get rid of this feeling. Our quarrel is not with the British people, we fight their imperialism. The proposal for the withdrawal of British power did not come out of anger. It came to enable India to play its due part at the present critical juncture. It is not a happy position for a big country like India to be merely helping with money and material obtained willy-nilly from her while the United Kingdom is conducting the war. We cannot evoke the true spirit of sacrifice and valor, so long as we are not free. I know the British Government will not be able to withhold freedom from us, when we have made enough self-sacrifice. We must, therefore, purge ourselves of hatred. Speaking for myself, I can say that I have never felt any hatred. As a matter of fact, I feel myself to be a greater friend of the British now than ever before. One reason is that they are today in distress. My very friendship, therefore, demands that I should try to save them from their mistakes. As I view the situation, they are on the brink of an abyss. It, therefore, becomes my duty to warn them of their danger even though it may, for the time being, anger them to the point of cutting off the friendly hand that is stretched out to help them. People may laugh, nevertheless that is my claim. At a time when I may have to launch the biggest struggle of my life, I may not harbor hatred against anybody.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 Jha, Sadan. 2010. "Mahatma Gandhi's Speech To The All India Congress Committee: Document Analysis." Milestone Documents in World History.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Traboulay, David M. 1997. Mahatma Gandhi's Satyagraha and Non Violent Resistance. City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nanda, B.. "Mahatma Gandhi." Encyclopedia Britannica, January 26, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mahatma-Gandhi.

- ↑ Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopaedia. "Indian National Congress." Encyclopedia Britannica, September 23, 2020. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Indian-National-Congress.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Sharma, Shivani. 1990. Quit India Movement, 1-116. Department of Political Science Aligarh Muslim University (India).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Shukla, Vivekananda.1989. Rebellion of 1942: Quit India Movement. H.K. Publishers & Distributors, Delhi; New Delhi

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Nanda, B.. "Mahatma Gandhi." Encyclopedia Britannica, January 26, 2022. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Mahatma-Gandhi.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Hutchins, Francis G. 1973. India's Revolution; Gandhi and the Quit India Movement. Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Parel, Anthony J. 1997. “Gandhi's ‘Quit India’ Speech, 1942.” Chapter. Gandhi: 'Hind Swaraj' and Other Writings. Cambridge Texts in Modern Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 181–87.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Schiler, Karen Elisabeth. 2010. "A Movable Ethos: How Ethics and Rhetoric can Imagine and Invite New Publics." ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Boissoneault, Lorraine. 2017. “The Speech That Brought India to the Brink of Independence.” Smithsonian.com, Smithsonian Institution.