Paraguayan War

| Paraguayan War | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

From top, left to right: the Battle of Riachuelo (1865), the Battle of Tuyutí (1866), the Battle of Curupayty (1866), the Battle of Avay (1868), the Battle of Lomas Valentinas (1868), the Battle of Acosta Ñu (1869), the Palacio de los López during the occupation of Asunción (1869), and Paraguayan war prisoners (c. 1870) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

| ||||||||

|

Total: 150,000–500,000 dead ...further details | |||||||||

The Paraguayan War, also known as the War of the Triple Alliance, was a South American war that lasted from 1864 to 1870. It was fought between Paraguay and the Triple Alliance of Argentina, the Empire of Brazil, and Uruguay. It was the deadliest and bloodiest inter-state war in Latin American history.[6] Paraguay sustained large casualties, but even the approximate numbers are disputed. Paraguay was forced to cede disputed territory to Argentina and Brazil. The war began in late 1864, as a result of a conflict between Paraguay and Brazil caused by the Uruguayan War. Argentina and Uruguay entered the war against Paraguay in 1865, and it then became known as the "War of the Triple Alliance".

After Paraguay was defeated in conventional warfare, it conducted a drawn-out guerrilla resistance, a strategy that resulted in the further destruction of the Paraguayan military and the civilian population. Much of the civilian population died due to battle, hunger, and disease. The guerrilla war lasted for 14 months until president Francisco Solano López was killed in action by Brazilian forces in the Battle of Cerro Corá on 1 March 1870. Argentine and Brazilian troops occupied Paraguay until 1876.

Background[edit]

Territorial disputes[edit]

Since their independence from Portugal and Spain in the early 19th century, the Empire of Brazil and the Spanish-American countries of South America were troubled by territorial disputes. Each nation in this region had boundary conflicts with multiple neighbors. Most had overlapping claims to the same territories, due to unresolved questions which stemmed from their former metropoles. Signed by Portugal and Spain in 1494, the Treaty of Tordesillas proved ineffective in the following centuries, as both colonial powers expanded their frontiers in South America and elsewhere. The outdated boundary lines did not represent the actual occupation of lands by the Portuguese and Spanish.[7]

By the early 1700s, the Treaty of Tordesillas was deemed not useful, and it was clear to both parties that a newer treaty had to be drawn based on feasible boundaries. In 1750, the Treaty of Madrid separated the Portuguese and Spanish areas of South America in lines that mostly corresponded to present-day boundaries.[8] Neither Portugal nor Spain was satisfied with the results, and new treaties were signed in the following decades that either established new territorial lines or repealed them. The final accord signed by both powers, the 1801 Treaty of Badajoz, reaffirmed the validity of the previous Treaty of San Ildefonso (1777), which had derived from the earlier Treaty of Madrid.[9]

The territorial disputes became worse when the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata collapsed in the early 1810s, leading to the rise of Argentina, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Uruguay. Historian Pelham Horton Box wrote: "Imperial Spain bequeathed to the emancipated Spanish-American nations not only her own frontier disputes with Portuguese Brazil but problems which had not disturbed her, relating to the exact boundaries of her own viceroyalties, captaincies general, audiencias and provinces."[10] Once separated the three countries quarreled over lands that were mostly uncharted or unknown. They were either sparsely populated or settled by indigenous tribes that answered to no parties.[11][12] In the case of Paraguay and Brazil, the problem was to define whether the Apa or Branco rivers should represent their actual boundary, a persistent issue that had confused Spain and Portugal in the late 18th century. A few indigenous tribes populated the region between the two rivers, and these tribes would attack Brazilian and Paraguayan settlements that were local to them.[13][14]

Political situation before the war[edit]

There are several theories regarding the origins of the war. The traditional view emphasizes that the policies of Paraguayan president Francisco Solano López used the Uruguayan War as a pretext to gain control of the Platine basin. That caused a response from the regional hegemons, Brazil and Argentina, both of which exercised influence over the much smaller republics of Uruguay and Paraguay. The war has also been attributed to the aftermath of colonialism in South America with border conflicts between the new states, the struggle for power among neighboring nations over the strategic Río de la Plata region, Brazilian and Argentine meddling in internal Uruguayan politics (which had already caused the Platine War), Solano López's efforts to help his allies in Uruguay (which had been defeated by the Brazilians), and his presumed expansionist ambitions.[15]

A strong military was developed because Paraguay's larger neighbors, Argentina and Brazil, had territorial claims against it and wanted to dominate it politically, much as both had already done in Uruguay. Paraguay had recurring boundary disputes and tariff issues with Argentina and Brazil for many years during the rule of Solano Lopez's predecessor and father, Carlos Antonio López.

Regional tension[edit]

In the time since Brazil and Argentina had become independent, their struggle for hegemony in the Río de la Plata region had profoundly marked the diplomatic and political relations among the countries of the region.[16]

Brazil was the first country to recognize the independence of Paraguay, in 1844. At this time Argentina still considered it a breakaway province. While Argentina was ruled by Juan Manuel Rosas (1829–1852), a common enemy of both Brazil and Paraguay, Brazil contributed to the improvement of the fortifications and development of the Paraguayan army, sending officials and technical help to Asunción.

As no roads linked the inland province of Mato Grosso to Rio de Janeiro, Brazilian ships needed to travel through Paraguayan territory, going up the Paraguay River to arrive at Cuiabá. However, Brazil had difficulty obtaining permission from the government in Asunción to freely use the Paraguay River for its shipping needs.

Uruguayan prelude[edit]

Brazil had carried out three political and military interventions in the politically unstable Uruguay:

- in 1851 against Manuel Oribe in order to fight Argentine influence in the country and to end the Great Siege of Montevideo;

- in 1855, at the request of the Uruguayan government and Venancio Flores, leader of the Colorado Party, which was traditionally supported by the Brazilian Empire;

- in 1864, against Atanasio Aguirre. This last intervention would lead to the Paraguayan War.

On 19 April 1863, Uruguayan general Venancio Flores, who was then an officer in the Argentine army as well as the leader of the Colorado Party of Uruguay,[17] invaded Uruguay, starting the Cruzada Libertadora with the covert support of Argentina, which supplied the rebels with arms, ammunition and 2,000 men.[18] Flores wanted to overthrow the Blanco Party government of president Bernardo Berro,[19]:24 which was allied with Paraguay.[19]:24

Paraguayan president López sent a note to the Argentine government on 6 September 1863, asking for an explanation, but Buenos Aires denied any involvement in Uruguay.[19]:24 From that moment, mandatory military service was introduced in Paraguay; in February 1864, an additional 64,000 men were drafted into the army.[19]:24

One year after the beginning of the Cruzada Libertadora, in April 1864, Brazilian minister José Antônio Saraiva arrived in Uruguayan waters with the Imperial Fleet, to demand payment for damages caused to Rio Grande do Sul farmers in border conflicts with Uruguayan farmers. Uruguayan president Atanasio Aguirre, from the Blanco Party, rejected the Brazilian demands, presented his own demands, and asked Paraguay for help.[20] To settle the growing crisis, Solano López offered himself as a mediator of the Uruguayan crisis, as he was a political and diplomatic ally of the Uruguayan Blancos, but the offer was turned down by Brazil.[21]

Brazilian soldiers on the northern borders of Uruguay started to provide help to Flores' troops and harassed Uruguayan officers, while the Imperial Fleet pressed hard on Montevideo.[22] During the months of June–August 1864 a Cooperation Treaty was signed between Brazil and Argentina at Buenos Aires, for mutual assistance in the Plate Basin Crisis.[23]

Brazilian minister Saraiva sent an ultimatum to the Uruguayan government on 4 August 1864: either comply with the Brazilian demands, or the Brazilian army would retaliate.[24] The Paraguayan government was informed of all this and sent to Brazil a message, which stated in part:

The government of the Republic of Paraguay will consider any occupation of the Oriental territory [i.e. Uruguay] as an attempt against the equilibrium of the states of the Platine Region which interests the Republic of Paraguay as a guarantee for its security, peace, and prosperity; and that it protests in the most solemn manner against the act, freeing itself for the future of every responsibility that may arise from the present declaration.

— José Berges, Paraguayan chancellor, to Vianna de Lima, Brazilian minister to the Paraguayan government. 30 August 1864.[25]

The Brazilian government, probably believing that the Paraguayan threat would be only diplomatic, answered on 1 September, stating that "they will never abandon the duty of protecting the lives and interests of Brazilian subjects." But in its answer, two days later, the Paraguayan government insisted that "if Brazil takes the measures protested against in the note of August 30th, 1864, Paraguay will be under the painful necessity of making its protest effective."[26]

On 12 October, despite the Paraguayan notes and ultimatums, Brazilian troops under the command of general João Propício Mena Barreto invaded Uruguay.[19]:24 This was not the start of the Paraguayan war, however, for Paraguay continued to maintain diplomatic relations with Brazil for another month.

On 11 November the Brazilian ship Marquês de Olinda, on her routine voyage up the River Paraguay to the Brazilian Mato Grosso, and carrying the new governor of that province, docked at Asunción and took on coal. Completing the formalities, she continued on her journey. According to one source, López hesitated whether to break the peace for a whole day, saying "If we don't have a war now with Brazil, we shall have one at a less convenient time for ourselves".[27] López then ordered the Paraguayan ship Tacuarí to pursue her and compel her return. On 12 November Tacuarí caught up with Marquês de Olinda in the vicinity of Concepción, fired across her bows, and ordered her to return to Asunción; when she arrived on the 13th, all on board were arrested. On the 12th, Paraguay informed the Brazilian minister in Asunción that diplomatic relations had been broken off.[28]

The conflict between Brazil and Uruguay was settled in February 1865. News of the war's end was brought by Pereira Pinto and met with joy in Rio de Janeiro. Brazilian emperor Pedro II found himself waylaid by a crowd of thousands in the streets amid acclamations.[29][30] However, public opinion quickly changed for the worse when newspapers began running stories painting the convention of 20 February as harmful to Brazilian interests, for which the cabinet was blamed. The newly promoted Viscount of Tamandaré and Mena Barreto (now Baron of São Gabriel) had supported the peace accord.[31] Tamandaré changed his mind soon afterward and played along with the allegations. A member of the opposition party, José Paranhos, Viscount of Rio Branco, was used as a scapegoat by the emperor and the government and was recalled in disgrace to the imperial capital.[32] The accusation that the convention had failed to meet Brazilian interests proved to be unfounded. Not only had Paranhos managed to settle all Brazilian claims, but by preventing the death of thousands, he gained a willing and grateful Uruguayan ally instead of a dubious and resentful one, which provided Brazil with an important base of operations during the acute clash with Paraguay that shortly ensued.[33]

Course of the war[edit]

Paraguayan offensive[edit]

In Mato Grosso[edit]

Paraguay took the initiative during the first phase of the war, launching the Mato Grosso Campaign by invading the Brazilian province of Mato Grosso on 14 December 1864,[19]:25 followed by an invasion of the Rio Grande do Sul province in the south in early 1865 and the Argentine Corrientes.

Two separate Paraguayan forces invaded Mato Grosso simultaneously. An expedition of 3,248 troops, commanded by Vicente Barrios, was transported by a naval squadron under the command of frigate captain Pedro Ignacio Meza up the Paraguay River to the town of Concepción.[19]:25 There they attacked the New Coimbra Fort on 27 December 1864.[19]:26 The Brazilian garrison of 154 men resisted for three days, under the command of Hermenegildo Portocarrero (later Baron of Fort Coimbra). When their munitions were exhausted, the defenders abandoned the fort and withdrew up the river towards Corumbá on board the gunship Anhambaí.[19]:26 After occupying the fort, the Paraguayans advanced further north, taking the cities of Albuquerque, Tage and Corumbá in January 1865.[19]:26

Solano López then sent a detachment to attack the military frontier post of Dourados. On 29 December 1864, this detachment, led by Martín Urbieta, encountered tough resistance from Antônio João Ribeiro and his 16 men, who were all eventually killed. The Paraguayans continued to Nioaque and Miranda, defeating the troops of José Dias da Silva. The city of Coxim was taken in April 1865. The second Paraguayan column, formed from some of the 4,650 men led by Francisco Isidoro Resquín at Concepción, penetrated into Mato Grosso with 1,500 troops.[19]:26

Despite these victories, the Paraguayan forces did not continue to Cuiabá, the capital of the province, where Augusto Leverger had fortified the camp of Melgaço. Their main objective was the capture of the gold and diamond mines, disrupting the flow of these materials into Brazil until 1869.[19]:27

Brazil sent an expedition to fight the invaders in Mato Grosso. A column of 2,780 men led by Manuel Pedro Drago left Uberaba in Minas Gerais in April 1865 and arrived at Coxim in December, after a difficult march of more than 2,000 kilometres (1,200 mi) through four provinces. However, Paraguay had already abandoned Coxim by December. Drago arrived at Miranda in September 1866, and the Paraguayans had left once again. Colonel Carlos de Morais Camisão assumed command of the column in January 1867—now with only 1,680 men—and decided to invade Paraguayan territory, which he penetrated as far as Laguna[34] where Paraguayan cavalry forced the expedition to retreat.

Despite the efforts of Camisão's troops and the resistance in the region, which succeeded in liberating Corumbá in June 1867, a large portion of Mato Grosso remained under Paraguayan control. The Brazilians withdrew from the area in April 1868, moving their troops to the main theatre of operations, in the south of Paraguay.

Paraguayan invasion of Corrientes and Rio Grande do Sul[edit]

The invasion of Corrientes and Rio Grande do Sul was the second phase of the Paraguayan offensive. In order to support the Uruguayan Blancos, the Paraguayans had to travel across Argentine territory. In January 1865, Solano López asked Argentina's permission for an army of 20,000 men (led by general Wenceslao Robles) to travel through the province of Corrientes.[19]:29–30 Argentine president Bartolomé Mitre refused Paraguay's request and a similar one from Brazil.[19]:29

After this refusal, the Paraguayan Congress gathered at an emergency meeting on 5 March 1865. After several days of discussions, on 23 March Congress decided to declare war on Argentina for its policies, hostile to Paraguay and favourable to Brazil, and then they conferred to Francisco Solano López the rank of Field Marshal of the Republic of Paraguay. The declaration of war was sent on 29 March 1865 to Buenos Aires.[35]

On 13 April 1865, a Paraguayan squadron sailed down the Paraná River and attacked two Argentine ships in the port of Corrientes. Immediately general Robles' troops took the city with 3,000 men, and a cavalry force of 800 arrived the same day. Leaving a force of 1,500 men in the city, Robles advanced southwards along the eastern bank.[19]:30

Along with Robles' troops, a force of 12,000 soldiers under colonel Antonio de la Cruz Estigarribia crossed the Argentine border south of Encarnación in May 1865, driving for Rio Grande do Sul. They traveled down the Uruguay River and took the town of São Borja on 12 June. Uruguaiana, to the south, was taken on 6 August with little resistance.

By invading Corrientes, Solano López had hoped to gain the support of the powerful Argentine caudillo Justo José de Urquiza, governor of the provinces of Corrientes and Entre Ríos, who was known to be the chief federalist hostile to Mitre and the central government in Buenos Aires.[36] However, Urquiza gave his full support to an Argentine offensive.[19]:31 The forces advanced approximately 200 kilometres (120 mi) south before ultimately ending the offensive in failure.

Following the invasion of the Corrientes Province by Paraguay on 13 April 1865, a great uproar stirred in Buenos Aires as the public learned of Paraguay's declaration of war. President Bartolomé Mitre made a famous speech to the crowds on 4 May 1865:

...My fellow countrymen, I promise you: in three days we shall be at the barracks. In three weeks, at the frontiers. And in three months in Asunción![37]

The same day, Argentina declared war on Paraguay;[19]:30–31 however, on 1 May 1865, Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay had signed the secret Treaty of the Triple Alliance in Buenos Aires. They named Bartolomé Mitre, president of Argentina, as supreme commander of the allied forces.[36] The signatories of the treaty were Rufino de Elizalde (Argentina), Otaviano de Almeida (Brazil) and Carlos de Castro (Uruguay).

On 11 June 1865, at the naval Battle of Riachuelo, the Brazilian fleet commanded by admiral Francisco Manoel Barroso da Silva destroyed the Paraguayan navy and prevented the Paraguayans from permanently occupying Argentine territory. For all practical purposes, this battle decided the outcome of the war in favor of the Triple Alliance; from that point onward, it controlled the waters of the Río de la Plata basin up to the entrance to Paraguay.[38]

A separate Paraguayan division of 3,200 men that continued towards Uruguay under the command of Pedro Duarte, who was then defeated by Allied troops under Venancio Flores in the bloody Battle of Yatay, on the banks of the Uruguay River, near Paso de los Libres.

While Solano López ordered the retreat of the forces that had occupied Corrientes, the Paraguayan troops that invaded São Borja advanced, taking Itaqui and Uruguaiana. The situation in Rio Grande do Sul was chaotic, and the local Brazilian military commanders were incapable of mounting effective resistance to the Paraguayans.[39]

The baron of Porto Alegre set out for Uruguaiana, a small town in the province's west, where the Paraguayan army was besieged by a combined force of Brazilian, Argentine and Uruguayan units.[40] Porto Alegre assumed command of the Brazilian army in Uruguaiana on 21 August 1865.[41] On 18 September, the Paraguayan garrison surrendered without further bloodshed.[42]

Allied counterattack[edit]

In subsequent months, the Paraguayans were driven out of the cities of Corrientes and San Cosme, the only Argentine territory still in Paraguayan possession.

By the end of 1865, the Triple Alliance was on the offensive. Its armies numbered 42,000 infantry and 15,000 cavalry as they invaded Paraguay in April.[19]:51–52 The Paraguayans scored small victories against major forces in the Battle of Corrales (also known as battle of Pehuajó or Itati) in the Corrientes Province, but it could not stop the invasion.[43]

Invasion of Paraguay[edit]

On 16 April 1866, the Allied armies invaded Paraguayan mainland by crossing the Paraná River.[44] López launched counterattacks, but they were repelled by general Manuel Luís Osório, who took victories in the battles of Itapirú and Isla Cabrita. Yet, the Allied advance was checked in the first major battle of the war, at Estero Bellaco, on 2 May 1866.[45]

Solano López, believing that he could deal a fatal blow to the Allies, launched a major offensive with 25,000 men against 35,000 Allied soldiers at the Battle of Tuyutí on 24 May 1866, one of the bloodiest battles in Latin-American history.[46] Despite being very close to victory at Tuyutí, López's plan was shattered by the Allied army's fierce resistance and the decisive action of the Brazilian artillery.[47] Both sides sustained heavy losses: more than 12,000 casualties for Paraguay versus 6,000 for the Allies.[48][49]

By 18 July, the Paraguayans had recovered, defeating forces commanded by Mitre and Flores in the Battle of Sauce and Boquerón, losing more than 2,000 men against the Allied 6,000 casualties.[50] However, Brazilian general Porto Alegre[51] won the Battle of Curuzú, putting the Paraguayans in a desperate situation.[52]

On 12 September 1866, after the defeat in the Battle of Curuzú, Solano López invited Mitre and Flores to a conference in Yataytí Corá, which resulted in a "heated argument" among both leaders.[19]:62 López had realized that the war was lost and was ready to sign a peace treaty with the Allies.[53] However, no agreement was reached, since Mitre's conditions for signing the treaty were that every article of the Treaty of the Triple Alliance was to be carried out, a condition that Solano López refused.[53] Article 6 of the treaty made truce or peace with López nearly impossible, as it stipulated that the war was to continue until the then government ceased to be, which meant the removal of Solano López.

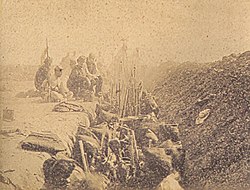

Allied setback at Curupayty: their advance comes to a halt[edit]

After the conference, the Allies marched into Paraguayan territory, reaching the defensive line of Curupayty. Trusting their numerical superiority and the possibility of attacking the flank of the defensive line through the Paraguay River by using the Brazilian ships, the Allies made a frontal assault on the defensive line, supported by the flank fire of the battleships.[54] However, the Paraguayans, commanded by general José E. Díaz, stood strong in their positions and set up for a defensive battle, inflicting tremendous damage on the attacking Allied troops, resulting in over 8,000 casualties on the Brazil-Argentine army against no more than 250 losses of the Paraguayans.[55] The Battle of Curupayty resulted in an almost catastrophic defeat for the Allied forces, ending their offensive for ten months, until July 1867.[19]:65

The Allied leaders blamed each other for the disastrous failure at Curupayty. General Flores left for Uruguay in September 1866 shortly after the battle and was later murdered there in 1867. Porto Alegre and Tamandaré found common ground in their distaste for the Brazilian commander of the 1st Corps, field marshal Polidoro Jordão. General Jordão was ostracized for supporting Mitre and for being a member of the Conservative Party, while Porto Alegre and Tamandaré were Progressives.[56]

General Porto Alegre also blamed Mitre for the tremendous defeat, saying:

Here is the result of the Brazilian government's lack of confidence in its generals and giving its Armies to foreign generals.[57]

Mitre had a harsh opinion of the Brazilians and said that "Porto Alegre and Tamandaré, who are cousins, and cousins even in lack of judgement have made a family pact to monopolize, in practice, the command of war." He further criticized Porto Alegre: "It is impossible to imagine a greater military nullity than this general, to which it can be added Tamandaré's dominating bad influence over him and the negative spirit of both in relation to the allies, owning to passions and petty interests."[56]

Siege of Humaitá[edit]

Caxias assumes command[edit]

The Brazilian government decided to create a unified command over Brazilian forces operating in Paraguay and turned to the 63-year-old Luís Alves de Lima e Silva, the Marquess of Caxias, as the new leader on 10 October 1866.[58] Osório was sent to organize a 5,000-strong third corps of the Brazilian army in Rio Grande do Sul.[19]:68 Caxias arrived in Itapiru on 17 November.[59] His first measure was to dismiss vice-admiral Tamandaré. The government had appointed Caxias' fellow Conservative vice-admiral Joaquim José Inácio—later the Viscount of Inhaúma—to lead the navy.[59]

The Marquess of Caxias assumed command on 19 November.[60] He aimed to end the never-ending squabbling among the allied commanders and to increase his autonomy from the Brazilian government.[61] With the departure of president Mitre in February 1867, Caxias assumed overall command of the Allied forces.[19]:65 He found the army practically paralyzed and devastated by disease. During this period Caxias trained his soldiers, re-equipped the army with new guns, improved the quality of the officer corps, and upgraded the health corps and overall hygiene of the troops, putting an end to epidemics.[62] From October 1866 until July 1867, all offensive operations were suspended.[63] Military operations were limited to skirmishes with the Paraguayans and bombarding Curupayty. Solano López took advantage of the disorganization of the enemy to reinforce the Fortress of Humaitá.[19]:70

The advance resumes: fall of Humaitá[edit]

As the Brazilian army was ready for combat, Caxias sought to encircle Humaitá and force its capitulation by siege. To aid the war effort, Caxias used observation balloons to gather information of the enemy lines.[64] With the 3rd Corps ready for combat, the Allied army started its flanking march around Humaitá on 22 July.[64] The march to outflank the left-wing of the Paraguayan fortifications constituted the basis of Caxias' tactics. He wanted to bypass the Paraguayan strongholds, cut the connections between Asunción and Humaitá and finally encircle the Paraguayans. The 2nd Corps was stationed in Tuyutí, while the 1st corps and the newly created 3rd Corps were used by Caxias to encircle Humaitá.[65] President Mitre returned from Argentina and re-assumed overall command on 1 August.[66] With the capture on 2 November by Brazilian troops of the Paraguayan position of Tahí, at the shores of the river, Humaitá would become isolated from the rest of the country by land.[67][lower-alpha 1]

The combined Brazilian, Argentine, and Uruguayan army continued advancing north through hostile territory to surround Humaitá. The Allied force advanced to San Solano on the 29th and Tayi on 2 November, isolating Humaitá from Asunción.[69] Before dawn on 3 November, Solano López reacted by ordering the attack on the rearguard of the allies in the Second Battle of Tuyutí.[19]:73

The Paraguayans, commanded by general Bernardino Caballero breached the Argentine lines, causing enormous damage to the Allied camp and successfully capturing weapons and supplies, much needed for the Paraguayan war effort.[70] Only thanks to the intervention of Porto Alegre and his troops, the Allied army recovered.[71] During the Second Battle of Tuyutí, Porto Alegre fought with his saber in hand-to-hand combat and lost two horses.[72] In this battle, the Paraguayans lost over 2,500 men, while the allies had just over 500 casualties.[73]

By 1867, Paraguay had lost 60,000 men to battle casualties, injuries, or disease.

Notes[edit]

Reference[edit]

- ↑ Whigham 2002, pp. 161, 446 n.87.

- ↑ Doratioto 2022, p. 483.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Doratioto 2022, p. 488.

- ↑ "Las mayores guerras y genocidios del siglo XIXs". Victimario Histórico Militar (in español). De Re Militari. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ↑ "De re Militari: muertos en Guerras, Dictaduras y Genocidios". remilitari.com.

- ↑ [Bethell, Leslie, The Paraguayan War, p.1]

- ↑ França, Arthur; Assumpção, Marla; Dorfman, Adriana (2016). "Fronteiras Sul-americanas: História, formas e processos contemporâneos". Anuário Unbral das Fronteiras Brasileiras (in português). 2: 79–123. doi:10.21826/2525-913X-2015-2p97-123. hdl:10183/150150.

- ↑ Owens, David (1993). "Spanish—Portuguese Territorial Rivalry in Colonial Río de la Plata". Yearbook (Conference of Latin Americanist Geographers). 19: 15–24. JSTOR 25765781.

- ↑ Giorgis, Luiz (2021). "220 anos do Tratado de Badajoz e da posse das Missões do RS pelos luso-brasileiros". Revista do IGHMB (in português). 108: 58–71.

- ↑ Box 1967, p. 54.

- ↑ Box 1967, pp. 54–69.

- ↑ Whigham 2002, pp. 94–102.

- ↑ Box 1967, pp. 29–53.

- ↑ Whigham 2002, pp. 77–85.

- ↑ Miguel Angel Centeno, Blood and Debt: War and the Nation-State in Latin America, University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1957. p. 55. [ISBN missing]

- ↑ Whigham 2002, p. 118.

- ↑ Rosa 2008, p. 94.

- ↑ Thompson 1869, pp. 17–19.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 19.13 19.14 19.15 19.16 19.17 19.18 19.19 19.20 19.21 19.22 19.23 Hooker, T.D., 2008, The Paraguayan War, Nottingham: Foundry Books, ISBN 1901543153

- ↑ Herrera 1943, pp. 243–244.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, pp. 313–314.

- ↑ Herrera 1943, pp. 453–455.

- ↑ Pomer 2008, pp. 96–98.

- ↑ Box 1967, pp. 156–162.

- ↑ Weisiger 2013, p. 97.

- ↑ Thompson 1869, p. 20.

- ↑ Thompson 1869, p. 25.

- ↑ Whigham 2002, pp. 160–161, 446.

- ↑ Bormann 1907, p. 281.

- ↑ Tasso Fragoso 2009, Vol 1, p. 254.

- ↑ Schneider 2009, p. 99.

- ↑ Needell 2006, p. 227.

- ↑ Kraay & Whigham 2004, p. 123; Schneider 2009, p. 100; Whigham 2002, p. 236

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 341.

- ↑ Thompson 1869, pp. 40–45.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Scheina 2003, p. 319.

- ↑ Rosa 2008, p. 198.

- ↑ Scheina 2003, p. 320.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, pp. 175–179.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 180.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 181.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 183.

- ↑ Kolinski 1965, pp. 59–60.

- ↑ Kolinski 1965, p. 62.

- ↑ Amerlan 1902, p. 38.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 201.

- ↑ Leuchars 2002, pp. 120–134.

- ↑ Cancogni and Boris 1972, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Leuchars 2002, p. 135.

- ↑ O'Leary 2011, p. 234.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, pp. 234–235.

- ↑ Cancogni and Boris 1972, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Vasconsellos 1970, p. 108.

- ↑ Leuchars 2002, p. 150.

- ↑ Kolinski 1965, p. 97.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Doratioto 2003, p. 247.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 244.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 252.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Doratioto 2003, p. 253.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 276.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 278.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, pp. 280–282.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 284.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Doratioto 2003, p. 295.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 297.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 298.

- ↑ Baron of Jaceguay, "A Guerra do Paraguay", op. cit., p.134. Emilio Jourdan, cied by Augusto Tasso Fragoso, op. cit., vol. III, pp. 253, 257–258.

- ↑ Enrique I. Rottjer, op. cit., p. 199.

- ↑ Baron of Jaceguay, "A Guerra do Paraguay", op. cit., in baron of Jaceguay and Carlos Vidal de Oliveira, Quatro séculos de atividade marítima: Portugal e Brasil, Rio de Janeiro, Imprensa Nacional, 1900, pp. 166, 188; Romeu Beltrão, O vanguardeiro de Itororó, Santa Maria, RS, Câmara Municipal de Vereadores, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Amerlan 1902, pp. 99–102.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, pp. 311–312.

- ↑ Doratioto 2003, p. 312.

- ↑ Kolinski 1965, p. 132.

Bibliography[edit]

| Library resources about Paraguayan War |

- Abente, Diego (1987). "The War of the Triple Alliance". Latin American Research Review. 22 (2): 47–69. doi:10.1017/S0023879100022044. JSTOR 2503485. S2CID 157519561.

- Amerlan, Albert (1902). Nights on the Río Paraguay: Scenes on the Paraguayan War and Charactersketches. Buenos Aires: Herman Tjarks and Co.

- Bareiro, R., ed. (2007). Testimonios de la Guerra Grande: Muerte del mariscal López (in español). Vol. 1. Asunción: Servilibro. ISBN 9789995300326.

- Bormann, José Bernardino (1907). A Campanha do Uruguay (1864–65) (in português). Rio de Janeiro: Imprensa Nacional.

- Box, Pelham Horton (1967). The origins of the Paraguayan War. New York: Russel & Russel.

- Burton, Richard Francis (1870). Letters from the Battlefields of Paraguay. London: Tinsley Brothers.

- Cancogni and Boris (1972). Il Napoleone del Plata (The Napoleon of the Plate) (in italiano). Milano: Rizzoli Editores.

- Cunninghame Graham, Robert Bontine (1933). Portrait of a Dictator: Francisco Solano López. London: William Heinemann Ltd.

- Davis, William H. (1977). "Question 1/77". Warship International. XIV (2): 161–172. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Doratioto, Francisco (2003). Maldita guerra: nova história da Guerra do Paraguai. Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-85-359-0224-2. Retrieved 19 June 2015.

- Doratioto, Francisco (2022). Maldita Guerra: Nova história da Guerra do Paraguai (in português) (3 ed.). São Paulo: Companhia das Letras. ISBN 978-65-5921-286-6.

- Ehlers, Hartmut (2004). "The Paraguayan Navy: Past and Present". Warship International. XLI (1): 79–97. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Ehlers, Hartmut (2004). "The Paraguayan Navy: Past and Present, Part II". Warship International. XLI (2): 173–206. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Gratz, George A. (1998). "Question 1/77: Warships of the War of the Triple Alliance". Warship International. XXXV (2): 210–211. ISSN 0043-0374.

- Hardy, Osgood (October 1919). "South American Alliances: Some Political and Geographical Considerations". Geographical Review. 8 (4/5): 259–265. Bibcode:1919GeoRv...8..259H. doi:10.2307/207840. JSTOR 207840.

- Herrera, Luis Alberto (1943). El Drama del 65: La Culpa Mitrista. Buenos Aires - Montevideo: Edición Homenaje.

- Hooker, Terry D. (2008). The Paraguayan War. Nottingham: Foundry Books. ISBN 978-1-901543-15-5.

- Jaceguay, Baron of (1900). "A Guerra do Paraguay: reflexões críticas sobre as operações combinadas da esquadra brasileira e exércitos aliados". Quatro séculos de atividade marítima: Portugal e Brasil. Imprensa Nacional.

- Kolinski, Charles J. (1965). Independence or Death! The story of the Paraguayan War. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

- Kraay, Hendrik; Whigham, Thomas L. (2004). I Die with My Country: Perspectives on the Paraguayan War, 1864–1870. Dexter, Michigan: Thomson-Shore. ISBN 978-0-8032-2762-0.

- Leuchars, Chris (2002). To the Bitter End: Paraguay and the War of the Triple Alliance. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-32365-8.

- Marley, David (1998). Wars of the Americas. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 0-87436-837-5.

- Mellid, Atilio García (1959). Proceso a los Falsificadores de la Historia del Paraguay (2 vols.) (in español). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Theoría.

- Nabuco, Joaquim (1901). La Guerra del Paraguay (in español). Buenos Aires: Ediciones Garnier.

- Needell, Jeffrey D. (2006). The Party of Order: the Conservatives, the State, and Slavery in the Brazilian Monarchy, 1831–1871. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5369-2.

- O'Leary, Juan (2011). Recuerdos de Gloria: Artículos Históricos sobre la Guerra de la Triple Alianza (in español). Asunción: Servilibro.

- Peñalba, José Alfredo Fornos (April 1982). "Draft Dodgers, War Resisters and Turbulent Gauchos: The War of the Triple Alliance against Paraguay". The Americas. 38 (4): 463–479. doi:10.2307/981208. JSTOR 981208. S2CID 251415406.

- Pomer, León (2008). La Guerra del Paraguay: Estado, Política y Negocios (in español). Buenos Aires: Editorial Colihue.

- Potthast, Barbata (2001). "Residentas, destinadas y otra heroinas: El nacionalismo paraguayo y el rol de las mujeres en la guerra de la Triple Alianza". In Potthast, Barbara; Scarxanella, Eugenia (eds.). Mujeres y naciones en América Latina" problemas de inclusión y exclusión (PDF). Frankfurt am Main: Vervuert. pp. 77–92. Retrieved 21 February 2022.

- Prado, Mário L. F. (2022). O Processo de Recuperação Econômica do Paraguai após a Guerra da Tríplice Aliança (1870 - 1890) (PDF) (Thesis). Universidade de São Paulo.

- Rosa, José María (2008). La Guerra del Paraguay y las Montoneras Argentinas (in español). Buenos Aires: Editorial Punto de Encuentro.

- Salles, Ricardo (2003). Guerra do Paraguai: Memórias & Imagens (in português). Rio de Janeiro: Bibilioteca Nacional.

- Scheina, Robert (2003). Latin America's Wars: The Age of the Caudillo, 1791–1899. Dulles, Virginia: Brassey's.

- Schneider, Louis (2009). A Guerra da Tríplice Aliança Contra o Paraguai (in português). Porto Alegre: Pradense. ISBN 978-85-89072-13-7.

- Shaw, Karl (2005) [2004]. Power Mad! [Šílenství mocných] (in čeština). Praha: Metafora. ISBN 978-80-7359-002-4.

- Tasso Fragoso, Augusto (2009). História da Guerra entre a Tríplice Aliança e o Paraguai (in português). Vol. 1 (3 ed.). Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca do Exército.

- Tate, E. N. (1979). "Britain and Latin America in the Nineteenth Century: The Case of Paraguay". Ibero-amerikanisches Archiv. Neue Folge. 5 (1): 39–70.

- Thompson, George (1869). The War in Paraguay: With a historical sketch of the country and its people and notes upon the military engineering of the war. London: Longmans and Green Co.

- Vasconsellos, Victor N. (1970). Resumen de Historia del Paraguay. Delimitaciones Territoriales. Asunción, Paraguay: Industria Grafica Comuneros.

- Washburn, Charles (1871). The history of Paraguay : with notes of personal observations, and reminiscences of diplomacy under difficulties (2 vols). Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Weisiger, Alex (2013). Logics of War: Explanations for Limited and Unlimited Conflicts. Ithaca, New York: Cornell University Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-0801468162.

Paraguay Brazil ultimatum.

- Whigham, Thomas (1994). "Paraguay and the World Cotton Market: The "Crisis" of the 1860s". Agricultural History. 68 (3): 1–15. JSTOR 3744146.

- Whigham, Thomas L. (2002). The Paraguayan War: Causes and Early Conduct. Vol. 1. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-4786-4.

- Whigham, Thomas L. (2017). The Road to Armageddon: Paraguay versus the Triple Alliance, 1866–70. Calgary, AB: University of Calgary Press. ISBN 978-1-55238-809-9.

- Williams, John Hoyt (1980). "The Undrawn Line: Three Centuries of Strife on the Paraguayan-Mato Grosso Frontier". Luso-Brazilian Review. University of Wisconsin Press. 17 (1): 17–40. JSTOR 3513374.

- Williams, John Hoyt (April 2000). "The Battle of Tuyuti". Military History. 17 (1): 58.

- Wilson, Peter (May 2004). "Latin America's Total War". History Today. 54 (5). ISSN 0018-2753.

- Template:Country study[title missing]