Hotan County

Hotan County

Gosthana, Gaustana, Khotan, Hotien | |

|---|---|

Farmland of Hotan County near the city | |

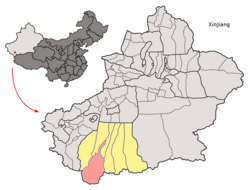

Location of Hotan County (red) in Hotan Prefecture (yellow) and Xinjiang | |

| Country | People's Republic of China |

| Autonomous region | Xinjiang |

| Prefecture | Hotan Prefecture |

| Population (2010)[1] | 269,941 |

| Ethnic groups | |

| • Major ethnic groups | Uyghur[2][3] |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (China Standard) |

| Website | htx |

| Hotan County |

|---|

Hotan County[4] (also known as Gosthana, Gaustana, Godana, Godaniya, Khotan, Hetian, Hotien)[5][6][7] is a county in the southwest of the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region and is under the administration of the Hotan Prefecture. Almost all the residents of the county are Uyghurs and live around oases situated between the desolate Taklamakan Desert and Kunlun Mountains. Hotan County is the southernmost county-level division of Xinjiang. The county borders Karakax/Moyu County to the northwest, Hotan City and Lop County to the northeast, Qira County to the east, Pishan County to the west, and (in Aksai Chin) Rutog County, Tibet to the southeast. Hotan County administers most of Aksai Chin,[8] an area disputed between China and India. The Line of Actual Control divides the India-controlled part of Ladakh union territory from the Aksai Chin area administered as part of southwest Hotan County.

Name[edit]

The area of Hotan is originally known as and has been historically referred to as Godana (Godaniya), a Sanskrit name meaning "Land of the cows". In Chinese, the same name is written as Yu-t'ien, pronounced as Gu-dana. It is referred to as Gosthana by local Tibetans, which also means the same in Sanskrit.[7]

History[edit]

On January 18, 1913, Hotan became a county.[8][9]

In 1919, Karakax/Moyu County was split off from Hotan County.[8]

In 1933, Muhammad Amin Bughra and his associates declared the Khotan Emirate.[9]

On December 22, 1949, the People's Liberation Army entered Hotan.[9]

In 1959, the Chinese character name for the county was set as .[8]

In 1962, some of the events of the Sino-Indian War occurred in the disputed Aksai Chin region.[10]

On April 12, 1969 during the Cultural Revolution, the Hotan County People's Government became the Hotan County Revolutionary Committee. In December 1979, the Hotan County Revolutionary Committee was disestablished and the Hotan County People's Government re-established.[9]

In 1983/4, the urban area of Hotan was administratively split from the larger Hotan County, and from then on governed as a county-level city.[8][11]

On September 9, 1995, Vice Premier Zhu Rongji visited Buzhake Township.[12]

On July 11, 2006, the township of Tusalla (Tushala), then part of Hotan County, was transferred to Hotan City.[1][11]

In 2012, Hanerik (Han'airike) was changed from a township into a town and Uzunsho (Wuzongxiao) township was established.[1]

On July 28, 2013, an incident involving Muslim protesters and local police in Hanerik (Han'airike/Hanairke) occurred.[13][14] Chinese state media said no one died during the confrontation. There were reports of protester deaths, as many as over 100.[15]

Geography[edit]

The northernmost point of the county is in the Taklamakan Desert at the confluence of the White Jade River and Karakash River, which together create the Hotan River.

Major lakes administered as part of Hotan County include the soda lakes Aksai Chin Lake and Surigh Yilganing Kol (Surigh-yilganing Köl; ),[16] both part of the disputed Aksai Chin. A Chinese military outpost called Tianshuihai[17] which is named for another lake, Tianshuihai ([16]), is also in the Hotan County administered part of the disputed Aksai Chin region. The Hotan County-administered part of Aksai Chin includes Tianwendian,[16] site of a Chinese military post.

Administrative divisions[edit]

Hotan County includes two towns, ten townships, and one other area:[1][18][2]

Towns:

Townships:

- Yengiawat[21] (Ying'awati; [22] / ), Yengierik (Ying'airike; / ), Bozak[23] (Buzhake,[12] Buzak,[24] Buzaq; / ), Layka (Layika, Layqa; / ), Langru ( / ), Tewekkul (Tawakule; [25] / ), Islamawat (Yisilamu'awati; / ), Seghizkol (Segezi Kule; / ), Qashteshi (Kashitashi;[26] / ), Uzunsho (Wuzongxiao; / )

Other:

- Hotan County Economic New Area ()

Economy[edit]

The county is known for Hotan Silk, Hotan Jade and Hotan Carpets. The county's agricultural products include wheat, rice, corn, melons, cotton, and silkworm cocoons.[8]

Demographics[edit]

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 261,498 | — |

| 2010 | 269,941 | +0.32% |

| [1] | ||

In 1997, the population of Hotan County was 99% Uyghur.[3]

As of 2015, 325,117 of the 327,533 residents of the county were Uyghur, 2,023 were Han Chinese and 393 were from other ethnic groups.[27]

In 2019, the population of Hotan County was 99% Uyghur.[2]

As of 1999, 99.41% of the population of Hotan (Hetian) County was Uyghur and 0.46% of the population was Han Chinese.[28]

Transportation[edit]

- China National Highway 315

- China National Highway 219, which passes through the disputed Aksai Chin region

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 和田县历史沿革 [Hotan County Historical Development] (in 中文(简体)). XZQH.org. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 和田县简介 [Hotan County Overview] (in 中文(简体)). 3 April 2019. Archived from the original on 18 January 2020. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 1997年和田县行政区划 [1997 Hotan County Administrative Divisions]. XZQH.org. 6 January 2011. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ The official spelling is "Hotan" according to Zhōngguó dìmínglù. 中国地名录. Beijing: SinoMaps Press. 1997. p. 304. ISBN 7-5031-1718-4.

- ↑ Higgins, Benjamin (November 1962). "The Philippines. Public Policy and National Economic Development. By Frank Golay. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1961. Xviii, 455. Map, Tables, Index, Bibliographic Essay". The Journal of Asian Studies. 22 (1): 114–116. doi:10.2307/2049929. JSTOR 2049929.

- ↑ "How Sanskrit Language is Associated with the Tibet and Xinjiang?". 5 February 2020.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Wang, Bangwei; Sen, Tansen (2011). India and China: Interactions through Buddhism and Diplomacy: A Collection of Essays by Professor Prabodh Chandra Bagchi. Anthem Press. p. 186. ISBN 9780857288219.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 夏征农; 陈至立, eds. (September 2009). 辞海:第六版彩图本 [Cihai (Sixth Edition in Color)] (in 中文). 上海. Shanghai: 上海辞书出版社. Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House. pp. 0008, 0866, 1610. ISBN 9787532628599.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 历史沿革 (in 中文(简体)). 22 March 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Calvin, James Barnard (April 1984). "The China-India Border War". Marine Corps Command and Staff College. Archived from the original on 11 November 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2011.

On October 24th, four days after the outbreak of heavy fighting in NEFA and Aksai Chin

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 和田市历史沿革 [Hotan City Historical Development] (in 中文(简体)). XZQH.org. 2 December 2014. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Zhu Rongji (2013). Zhu Rongji on the Record: The Road to Reform: 1991–1997. Translated by June Y. Mei. Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press. p. xvi. ISBN 9780815725190 – via Google Books.

Talking with Uyghur cotton growers in Buzhake Township, Hotan County, Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, on September 9, 1995.

- ↑ Chris Buckley (28 June 2013). "Violence Erupts Anew in Volatile Chinese Region". New York Times. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Shohret Hoshur, Joshua Lipes (28 July 2013). "Two Uyghurs Believed Killed in Hotan Violence". Radio Free Asia. Translated by Dolkun Kamberi and Luisetta Mudie. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Andrew Jacobs (26 August 2013). "Over News of Clash, a Shroud of Silence in Xinjiang". New York Times. Archived from the original on 30 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

Although the state media said that no one died during the confrontation between villagers and armed police officers, numerous sources say that dozens were shot dead on the highway that connects Hanerik to Hotan, which the Chinese call Hetian. Exile groups say the death toll may exceed 100.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 地貌气候 (in 中文(简体)). 29 April 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Robert Kerry; John Vincent Bellezza, eds. (February 2008). Tibet. Lonely Planet (7 ed.). p. 2, 339. ISBN 9781741045697 – via Internet Archive.

Tianshuihai{...}From here the road turns south, and climbs to the Khitai Pass (kilometre marker 535; 5150m), past the military base of Tianshuihai.

- ↑ 2018年统计用区划代码和城乡划分代码:和田县 [2018 Statistical Area Numbers and Rural-Urban Area Numbers: Hotan County] (in 中文(简体)). National Bureau of Statistics of the People's Republic of China. 2018. Archived from the original on 22 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ huaxia, ed. (17 September 2020). "Full Text: Employment and Labor Rights in Xinjiang". Xinhua News Agency. Retrieved 20 September 2020.

In 2019, a survey in three villages of Baghchi Town, Hotan County, Hotan Prefecture counted a total population of 5,307, with 1,699 people capable of work, of whom, 1,493, or 88 percent, were keen to work outside their home villages. Of the remainder, 180 preferred to work locally in township enterprises, village factories, or poverty-relief cooperatives offering an average monthly salary of RMB3,000; the other 26 wished to start businesses locally, engaging in transport and logistics, property management and household services, construction, hairdressing, catering or retail stores.

- ↑ Chen Xuejian, ed. (2008). Travel Around China. Hong Kong: HarperCollins. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-06-1473548 – via Internet Archive.

This ancient site is situated in the village of Yuetegan of the town of Bageqi, Hetian County, 8 miles from Hetian, covering about 4 square miles.

- ↑ Template:GEOnet2, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ↑ خوتەنلىك 171 دېھقان ئىشلەمچى ھۆددە ئايروپىلانغا ئولتۇرۇپ، خۇنەندىكى ئىش ئورنىغا ئىشلەشكە ماڭدى (in ئۇيغۇرچە / Uyghurche). 23 February 2020. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Xie Yuzhong (2003). 地名中的新疆 (in 中文(简体)). Ürümqi: 新疆人民出版社. p. 242. ISBN 7-228-08004-1.

Bozak

- ↑ Zhong Xingqi, ed. (July 2008). 西域地名考录 (in 中文(简体)). Beijing: 国家图书馆出版社. p. 163. ISBN 978-7-5013-3628-9.

bù zhā kè Buzak

- ↑ خوتەن ناھىيىسىنىڭ تەۋەككۈل يېزىسى «روپاشلىق» ئاياللارنىڭ يۈزىنى ئېچىشنى كادىرلارغا كۆتۈرىگە بەرگەن. Radio Free Asia (in ئۇيغۇرچە / Uyghurche). 10 May 2013. Retrieved 13 May 2020.

- ↑ Chu Meng (14 September 2007). "Russian plane arrives for missing tourists". Beijing Today. p. 2. Retrieved 23 December 2019 – via Internet Archive.

According to the original plan, the expedition team was to meet Zhang at Kashitashi Township in Hotan County, 30 kilometers from Hotan City.

- ↑ 3-7 各地、州、市、县(市)分民族人口数 (in 中文(简体)). Statistic Bureau of Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region. 15 March 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 3 September 2017.

- ↑ Morris Rossabi, ed. (2004). Governing China's Multiethnic Frontiers (PDF). University of Washington Press. p. 180. ISBN 0-295-98390-6. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2020-01-07. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

Coordinates: 37°05′26″N 79°49′44″E / 37.09056°N 79.82889°E

Template:Xinjiang Administrative Divisions