Design of bitcoin

Bitcoin is based on an elliptic curve called "secp256k1" and encrypted with the ECDSA algorithm. The equation for the Bitcoin secp256k1 curve is 2=3+7.[1] Bitcoin has a proposed Bitcoin Improvement Proposal (BIP) that would add support for Schnorr signatures.[2]:101

Units and divisibility[edit | edit source]

The unit of account of the bitcoin system is a bitcoin. Ticker symbols used to represent bitcoin are BTC[lower-alpha 1] and XBT.[lower-alpha 2][6]:2 Its Unicode character is ₿. Small amounts of bitcoin used as alternative units are millibitcoin (mBTC), and satoshi (sat). Named in homage to bitcoin's creator, a satoshi is the smallest amount within bitcoin representing 1⁄100000000 bitcoins, one hundred millionth of a bitcoin. A millibitcoin equals 1⁄1000 bitcoins; one thousandth of a bitcoin or 100,000 satoshis.[7]

Blockchain[edit | edit source]

The bitcoin blockchain is a public ledger that records bitcoin transactions.[10] It is implemented as a chain of blocks, each block containing a hash of the previous block up to the genesis block[lower-alpha 3] of the chain. A network of communicating nodes running bitcoin software maintains the blockchain.[11]:215–219 Transactions of the form payer X sends Y bitcoins to payee Z are broadcast to this network using readily available software applications.

Network nodes can validate transactions, add them to their copy of the ledger, and then broadcast these ledger additions to other nodes. To achieve independent verification of the chain of ownership each network node stores its own copy of the blockchain.[12] At varying intervals of time averaging to every 10 minutes, a new group of accepted transactions, called a block, is created, added to the blockchain, and quickly published to all nodes, without requiring central oversight. This allows bitcoin software to determine when a particular bitcoin was spent, which is needed to prevent double-spending. A conventional ledger records the transfers of actual bills or promissory notes that exist apart from it, but the blockchain is the only place that bitcoins can be said to exist in the form of unspent outputs of transactions.[13]:ch. 5

Individual blocks, public addresses and transactions within blocks can be examined using a blockchain explorer.[citation needed]

Supply[edit | edit source]

The successful miner finding the new block is allowed by the rest of the network to reward themselves with newly created bitcoins and transaction fees.[14] As of 11 May 2020[update], the reward amounted to 6.25 newly created bitcoins per block added to the blockchain, plus any transaction fees from payments processed by the block.[15] To mine half of the supply of bitcoins took four years but the remainder will take another 120 years, because of an artificial process called "bitcoin halving" according to which miners are compensated by fewer BTC as time goes on.[15] To claim the reward, a special transaction called a coinbase is included with the processed payments.[13]:ch. 8 All bitcoins in existence have been created in such coinbase transactions. The bitcoin protocol specifies that the reward for adding a block will be halved every 210,000 blocks (approximately every four years). Eventually, the reward will decrease to zero, and the limit of 21 million bitcoins[lower-alpha 4] will be reached c. 2140; the record keeping will then be rewarded solely by transaction fees.[16]

In other words, Nakamoto set a monetary policy based on artificial scarcity at bitcoin's inception that the total number of bitcoins could never exceed 21 million. New bitcoins are created roughly every ten minutes and the rate at which they are generated drops by half about every four years until all will be in circulation.[17]

Transactions[edit | edit source]

Transactions are defined using a Forth-like scripting language.[13]:ch. 5 Transactions consist of one or more inputs and one or more outputs. When a user sends bitcoins, the user designates each address and the amount of bitcoin being sent to that address in an output. To prevent double spending, each input must refer to a previous unspent output in the blockchain.[18] The use of multiple inputs corresponds to the use of multiple coins in a cash transaction. Since transactions can have multiple outputs, users can send bitcoins to multiple recipients in one transaction. As in a cash transaction, the sum of inputs (coins used to pay) can exceed the intended sum of payments. In such a case, an additional output is used, returning the change back to the payer.[18] Any input satoshis not accounted for in the transaction outputs become the transaction fee.[18]

Though transaction fees are optional, miners can choose which transactions to process and prioritize those that pay higher fees.[18] Miners may choose transactions based on the fee paid relative to their storage size, not the absolute amount of money paid as a fee. These fees are generally measured in satoshis per byte (sat/b). The size of transactions is dependent on the number of inputs used to create the transaction, and the number of outputs.[13]:ch. 8

The blocks in the blockchain were originally limited to 32 megabytes in size. The block size limit of one megabyte was introduced by Satoshi Nakamoto in 2010. Eventually the block size limit of one megabyte created problems for transaction processing, such as increasing transaction fees and delayed processing of transactions.[19] Andreas Antonopoulos has stated Lightning Network is a potential scaling solution and referred to lightning as a second layer routing network.[13]:ch. 8

Ownership[edit | edit source]

In the blockchain, bitcoins are registered to bitcoin addresses. Creating a bitcoin address requires nothing more than picking a random valid private key and computing the corresponding bitcoin address. This computation can be done in a split second. But the reverse, computing the private key of a given bitcoin address, is practically unfeasible.[13]:ch. 4 Users can tell others or make public a bitcoin address without compromising its corresponding private key. Moreover, the number of valid private keys is so vast that it is extremely unlikely someone will compute a key-pair that is already in use and has funds. The vast number of valid private keys makes it unfeasible that brute force could be used to compromise a private key. To be able to spend their bitcoins, the owner must know the corresponding private key and digitally sign the transaction. The network verifies the signature using the public key; the private key is never revealed.[13]:ch. 5

If the private key is lost, the bitcoin network will not recognize any other evidence of ownership;[11] the coins are then unusable, and effectively lost. For example, in 2013 one user claimed to have lost 7,500 bitcoins, worth $7.5 million at the time, when he accidentally discarded a hard drive containing his private key.[20] About 20% of all bitcoins are believed to be lost -they would have had a market value of about $20 billion at July 2018 prices.[21]

To ensure the security of bitcoins, the private key must be kept secret.[13]:ch. 10 If the private key is revealed to a third party, e.g. through a data breach, the third party can use it to steal any associated bitcoins.[22] As of December 2017[update], around 980,000 bitcoins have been stolen from cryptocurrency exchanges.[23]

Regarding ownership distribution, as of 16 March 2018, 0.5% of bitcoin wallets own 87% of all bitcoins ever mined.[24]

Mining[edit | edit source]

Mining is a record-keeping service done through the use of computer processing power.[lower-alpha 6] Miners keep the blockchain consistent, complete, and unalterable by repeatedly grouping newly broadcast transactions into a block, which is then broadcast to the network and verified by recipient nodes.[10] Each block contains a SHA-256 cryptographic hash of the previous block,[10] thus linking it to the previous block and giving the blockchain its name.[13]:ch. 7[10]

To be accepted by the rest of the network, a new block must contain a proof-of-work (PoW).[10] The system used is based on Adam Back's 1997 anti-spam scheme, Hashcash.[28][failed verification] The PoW requires miners to find a number called a nonce, such that when the block content is hashed along with the nonce, the result is numerically smaller than the network's difficulty target.[13]:ch. 8 This proof is easy for any node in the network to verify, but extremely time-consuming to generate, as for a secure cryptographic hash, miners must try many different nonce values (usually the sequence of tested values is the ascending natural numbers: 0, 1, 2, 3, ...[13]:ch. 8) before meeting the difficulty target.

Every 2,016 blocks (approximately 14 days at roughly 10 min per block), the difficulty target is adjusted based on the network's recent performance, with the aim of keeping the average time between new blocks at ten minutes. In this way the system automatically adapts to the total amount of mining power on the network.[13]:ch. 8 Between 1 March 2014 and 1 March 2015, the average number of nonces miners had to try before creating a new block increased from 16.4 quintillion to 200.5 quintillion.[29]

The proof-of-work system, alongside the chaining of blocks, makes modifications of the blockchain extremely hard, as an attacker must modify all subsequent blocks in order for the modifications of one block to be accepted.[30] As new blocks are mined all the time, the difficulty of modifying a block increases as time passes and the number of subsequent blocks (also called confirmations of the given block) increases.[10]

Computing power is often bundled together by a Mining pool to reduce variance in miner income. Individual mining rigs often have to wait for long periods to confirm a block of transactions and receive payment. In a pool, all participating miners get paid every time a participating server solves a block. This payment depends on the amount of work an individual miner contributed to help find that block.[31]

Wallets[edit | edit source]

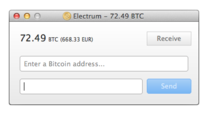

The first wallet program, simply named Bitcoin, and sometimes referred to as the Satoshi client, was released in 2009 by Satoshi Nakamoto as open-source software. In version 0.5 the client moved from the wxWidgets user interface toolkit to Qt, and the whole bundle was referred to as Bitcoin-Qt.[32] After the release of version 0.9, the software bundle was renamed Bitcoin Core to distinguish itself from the underlying network.[33][34] Bitcoin Core is, perhaps, the best known implementation or client. Alternative clients (forks of Bitcoin Core) exist, such as Bitcoin XT, Bitcoin Unlimited,[35] and Parity Bitcoin.[36]

A wallet stores the information necessary to transact bitcoins. While wallets are often described as a place to hold[37] or store bitcoins, due to the nature of the system, bitcoins are inseparable from the blockchain transaction ledger. A wallet is more correctly defined as something that "stores the digital credentials for your bitcoin holdings" and allows one to access (and spend) them.[13]:ch. 1, glossary Bitcoin uses public-key cryptography, in which two cryptographic keys, one public and one private, are generated.[38] At its most basic, a wallet is a collection of these keys.

There are several modes which wallets can operate in. They have an inverse relationship with regards to trustlessness and computational requirements.

- Full clients verify transactions directly by downloading a full copy of the blockchain (over 150 GB as of January 2018[update]).[39] They are the most secure and reliable way of using the network, as trust in external parties is not required. Full clients check the validity of mined blocks, preventing them from transacting on a chain that breaks or alters network rules.[13]:ch. 1 Because of its size and complexity, downloading and verifying the entire blockchain is not suitable for all computing devices.

- Lightweight clients consult full nodes to send and receive transactions without requiring a local copy of the entire blockchain (see simplified payment verification – SPV). This makes lightweight clients much faster to set up and allows them to be used on low-power, low-bandwidth devices such as smartphones. When using a lightweight wallet, however, the user must trust full nodes, as it can report faulty values back to the user. Lightweight clients follow the longest blockchain and do not ensure it is valid, requiring trust in full nodes.[40]

Third-party internet services called online wallets offer similar functionality but may be easier to use. In this case, credentials to access funds are stored with the online wallet provider rather than on the user's hardware.[41] As a result, the user must have complete trust in the online wallet provider. A malicious provider or a breach in server security may cause entrusted bitcoins to be stolen. An example of such a security breach occurred with Mt. Gox in 2011.[42]

Physical wallets store the credentials necessary to spend bitcoins offline and can be as simple as a paper printout of the private key:[13]:ch. 10 a paper wallet or more advanced such as a hardware wallet. A paper wallet is created with a keypair generated on a computer with no internet connection; the private key is written or printed onto the paper[lower-alpha 7] and then erased from the computer. The paper wallet can then be stored in a safe physical location for later retrieval. Bitcoins stored using a paper wallet are said to be in cold storage.[43]:39

Cameron and Tyler Winklevoss, the founders of the Gemini Trust Co. exchange, reported that they had cut their paper wallets into pieces and stored them in envelopes distributed to safe deposit boxes across the United States.[44] Through this system, the theft of one envelope would neither allow the thief to steal any bitcoins nor deprive the rightful owners of their access to them.[45]

Physical wallets can also take the form of metal token coins[46] with a private key accessible under a security hologram in a recess struck on the reverse side.[47]:38 The security hologram self-destructs when removed from the token, showing that the private key has been accessed.[48] Originally, these tokens were struck in brass and other base metals, but later used precious metals as bitcoin grew in value and popularity.[47]:80 Coins with stored face value as high as ₿1000 have been struck in gold.[47]:102–104 The British Museum's coin collection includes four specimens from the earliest series[47]:83 of funded bitcoin tokens; one is currently on display in the museum's money gallery.[49] In 2013, a Utahn manufacturer of these tokens was ordered by the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN) to register as a money services business before producing any more funded bitcoin tokens.[46][47]:80

Another type of physical wallet called a hardware wallet keeps credentials offline while facilitating transactions.[50] The hardware wallet acts as a computer peripheral and signs transactions as requested by the user, who must press a button on the wallet to confirm that they intended to make the transaction. Hardware wallets never expose their private keys, keeping bitcoins in cold storage even when used with computers that may be compromised by malware.[43]:42–45

Decentralization[edit | edit source]

Bitcoin is decentralized thus:

- Bitcoin does not have a central authority.

- There is no central server; the bitcoin network is peer-to-peer.[51]

- There is no central storage; the bitcoin ledger is distributed.[52]

- The ledger is public; anybody can store it on their computer.[13]:ch. 1

- There is no single administrator; the ledger is maintained by a network of equally privileged miners.[13]:ch. 1

- Anybody can become a miner.[13]:ch. 1

- The additions to the ledger are maintained through competition. Until a new block is added to the ledger, it is not known which miner will create the block.[13]:ch. 1

- The issuance of bitcoins is decentralized. They are issued as a reward for the creation of a new block.[14]

- Anybody can create a new bitcoin address (a bitcoin counterpart of a bank account) without needing any approval.[13]:ch. 1

- Anybody can send a transaction to the network without needing any approval; the network merely confirms that the transaction is legitimate.[53]:32

Conversely, researchers have pointed out at a "trend towards centralization". Although bitcoin can be sent directly from user to user, in practice intermediaries are widely used.[11]:220–222 Bitcoin miners join large mining pools to minimize the variance of their income.[11]:215, 219–222[54]:3[55] Because transactions on the network are confirmed by miners, decentralization of the network requires that no single miner or mining pool obtains 51% of the hashing power, which would allow them to double-spend coins, prevent certain transactions from being verified and prevent other miners from earning income.[56] As of 2013[update] just six mining pools controlled 75% of overall bitcoin hashing power.[56] In 2014 mining pool Ghash.io obtained 51% hashing power which raised significant controversies about the safety of the network. The pool has voluntarily capped their hashing power at 39.99% and requested other pools to act responsibly for the benefit of the whole network.[57] Around the year 2017, over 70% of the hashing power and 90% of transactions were operating from China.[58]

According to researchers, other parts of the ecosystem are also "controlled by a small set of entities", notably the maintenance of the client software, online wallets and simplified payment verification (SPV) clients.[56]

Privacy and fungibility[edit | edit source]

Bitcoin is pseudonymous, meaning that funds are not tied to real-world entities but rather bitcoin addresses. Owners of bitcoin addresses are not explicitly identified, but all transactions on the blockchain are public. In addition, transactions can be linked to individuals and companies through "idioms of use" (e.g., transactions that spend coins from multiple inputs indicate that the inputs may have a common owner) and corroborating public transaction data with known information on owners of certain addresses.[59] Additionally, bitcoin exchanges, where bitcoins are traded for traditional currencies, may be required by law to collect personal information.[60] To heighten financial privacy, a new bitcoin address can be generated for each transaction.[61]

Wallets and similar software technically handle all bitcoins as equivalent, establishing the basic level of fungibility. Researchers have pointed out that the history of each bitcoin is registered and publicly available in the blockchain ledger, and that some users may refuse to accept bitcoins coming from controversial transactions, which would harm bitcoin's fungibility.[62] For example, in 2012, Mt. Gox froze accounts of users who deposited bitcoins that were known to have just been stolen.[63]

Notes[edit | edit source]

- ↑ As of 2014[update], BTC is a commonly used code. It does not conform to ISO 4217 as BT is the country code of Bhutan, and ISO 4217 requires the first letter used in global commodities to be 'X'.

- ↑ As of 2014[update], XBT, a code that conforms to ISO 4217 though is not officially part of it, is used by Bloomberg L.P.,[3] CNNMoney,[4] and xe.com.[5]

- ↑ The genesis block is the block number 0. The timestamp of the block is 2009-01-03 18:15:05. This block is unlike all other blocks in that it does not have a previous block to reference.

- ↑ The exact number is 20,999,999.9769 bitcoins.[13]:ch. 8

- ↑ Relative mining difficulty is defined as the ratio of the difficulty target on 9 January 2009 to the current difficulty target.

- ↑ It is misleading to think that there is an analogy between gold mining and bitcoin mining. The fact is that gold miners are rewarded for producing gold, while bitcoin miners are not rewarded for producing bitcoins; they are rewarded for their record-keeping services.[27]

- ↑ The private key can be printed as a series of letters and numbers, a seed phrase, or a 2D barcode. Usually, the public key or bitcoin address is also printed, so that a holder of a paper wallet can check or add funds without exposing the private key to a device.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Houria, Azine; Mohamed Abdelkader, Bencherif; Abderezzak, Guessoum (2019-03-01). "A comparison between the secp256r1 and the koblitz secp256k1 bitcoin curves". Indonesian Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science. 13 (3): 910. doi:10.11591/ijeecs.v13.i3.pp910-918.

- ↑ Van Hijfte, Stijn (2020). Blockchain Platforms: A Look at the Underbelly of Distributed Platforms. Morgan & Claypool Publishers. ISBN 9781681738925.

- ↑ Romain Dillet (9 August 2013). "Bitcoin Ticker Available On Bloomberg Terminal For Employees". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Bitcoin Composite Quote (XBT)". CNN Money. CNN. Archived from the original on 27 October 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "XBT – Bitcoin". xe.com. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Regulation of Bitcoin in Selected Jurisdictions" (PDF). The Law Library of Congress, Global Legal Research Center. January 2014. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- ↑ Katie Pisa & Natasha Maguder (9 July 2014). "Bitcoin your way to a double espresso". cnn.com. CNN. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 23 April 2015.

- ↑ "Blockchair". Blockchair.com. Archived from the original on 13 October 2019. Retrieved 13 October 2019.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Charts". Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 3 November 2014. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 "The great chain of being sure about things". The Economist. The Economist Newspaper Limited. 31 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 July 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Rainer Böhme; Nicolas Christin; Benjamin Edelman; Tyler Moore (2015). "Bitcoin: Economics, Technology, and Governance". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 29 (2): 213–238. doi:10.1257/jep.29.2.213.

- ↑ Sparkes, Matthew (9 June 2014). "The coming digital anarchy". The Daily Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 23 January 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2015.

- ↑ 13.00 13.01 13.02 13.03 13.04 13.05 13.06 13.07 13.08 13.09 13.10 13.11 13.12 13.13 13.14 13.15 13.16 13.17 13.18 13.19 13.20 Antonopoulos, Andreas M. (April 2014). Mastering Bitcoin: Unlocking Digital Crypto-Currencies. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 978-1-4493-7404-4.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ashlee Vance (14 November 2013). "2014 Outlook: Bitcoin Mining Chips, a High-Tech Arms Race". Businessweek. Archived from the original on 21 November 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2013.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Browne, Ryan (2020-05-11). "Bitcoin investors are bracing for a key technical event — here's what you need to know". CNBC.

- ↑ Ritchie S. King; Sam Williams; David Yanofsky (17 December 2013). "By reading this article, you're mining bitcoins". qz.com. Atlantic Media Co. Archived from the original on 17 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ↑ Shin, Laura (24 May 2016). "Bitcoin Production Will Drop By Half In July, How Will That Affect The Price?". Forbes. Archived from the original on 24 May 2016. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Joshua A. Kroll; Ian C. Davey; Edward W. Felten (11–12 June 2013). "The Economics of Bitcoin Mining, or Bitcoin in the Presence of Adversaries" (PDF). The Twelfth Workshop on the Economics of Information Security (WEIS 2013). Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 26 April 2016.

A transaction fee is like a tip or gratuity left for the miner.

- ↑ Orcutt, Mike (19 May 2015). "Leaderless Bitcoin Struggles to Make Its Most Crucial Decision". MIT Technology Review. Archived from the original on 18 October 2017. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ↑ "Man Throws Away 7,500 Bitcoins, Now Worth $7.5 Million". CBS DC. 29 November 2013. Archived from the original on 15 January 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2014.

- ↑ Krause, Elliott (5 July 2018). "A Fifth of All Bitcoin Is Missing. These Crypto Hunters Can Help". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 9 July 2018. Retrieved 8 July 2018.

- ↑ Jeffries, Adrianne (19 December 2013). "How to steal Bitcoin in three easy steps". The Verge. Archived from the original on 27 July 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2014.

- ↑ Harney, Alexandra; Stecklow, Steve (16 November 2017). "Twice burned - How Mt. Gox's bitcoin customers could lose again". Reuters. Archived from the original on 29 August 2019. Retrieved 6 September 2018.

- ↑ Martindale, Jon (16 March 2018). "Who owns all the Bitcoin? A few billionaire whales in a small pond". Digital Trends. Archived from the original on 30 June 2019. Retrieved 1 July 2019.

- ↑ "Bitcoin mania is hurting PC gamers by pushing up GPU prices". 30 January 2018. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 2 February 2018.

- ↑ "Cryptocurrency mining operation launched by Iron Bridge Resources". World Oil. 26 January 2018. Archived from the original on 30 January 2018.

- ↑ Andolfatto, David (31 March 2014). "Bitcoin and Beyond: The Possibilities and Pitfalls of Virtual Currencies" (PDF). Dialogue with the Fed. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 April 2014. Retrieved 16 April 2014.

- ↑ Sherman, Alan; Javani, Farid; Golaszewski, Enis (25 March 2019). "On the Origins and Variations of Blockchain Technologies". IEEE Security and Policy. 17 (1): 72–77. arXiv:1810.06130. doi:10.1109/MSEC.2019.2893730. S2CID 53114747.

- ↑ "Difficulty History" (The ratio of all hashes over valid hashes is D x 4,295,032,833, where D is the published "Difficulty" figure.). Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 8 April 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- ↑ Hampton, Nikolai (5 September 2016). "Understanding the blockchain hype: Why much of it is nothing more than snake oil and spin". Computerworld. IDG. Archived from the original on 6 September 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2016.

- ↑ Biggs, John (8 April 2013). "How To Mine Bitcoins". Techcrunch. Archived from the original on 6 July 2017.

- ↑ Skudnov, Rostislav (2012). Bitcoin Clients (PDF) (Bachelor's Thesis). Turku University of Applied Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 18 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Bitcoin Core version 0.9.0 released". bitcoin.org. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- ↑ Metz, Cade (19 August 2015). "The Bitcoin Schism Shows the Genius of Open Source". Wired. Condé Nast. Archived from the original on 30 June 2016. Retrieved 3 July 2016.

- ↑ Vigna, Paul (17 January 2016). "Is Bitcoin Breaking Up?". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on 20 August 2016. Retrieved 8 November 2016.

- ↑ Allison, Ian (28 April 2017). "Ethereum co-founder Dr Gavin Wood and company release Parity Bitcoin". International Business Times. Archived from the original on 28 April 2017. Retrieved 28 April 2017.

- ↑ Adam Serwer & Dana Liebelson (10 April 2013). "Bitcoin, Explained". motherjones.com. Mother Jones. Archived from the original on 27 April 2014. Retrieved 26 April 2014.

- ↑ "Bitcoin: Bitcoin under pressure". The Economist. 30 November 2013. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ "Blockchain Size". Blockchain.info. Archived from the original on 27 May 2017. Retrieved 16 January 2018.

- ↑ Gervais, Arthur; O. Karame, Ghassan; Gruber, Damian; Capkun, Srdjan. "On the Privacy Provisions of Bloom Filters in Lightweight Bitcoin Clients" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 3 September 2016.

- ↑ Bill Barhydt (4 June 2014). "3 reasons Wall Street can't stay away from bitcoin". NBCUniversal. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ "MtGox gives bankruptcy details". bbc.com. BBC. 4 March 2014. Archived from the original on 12 March 2014. Retrieved 13 March 2014.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Barski, Conrad; Wilmer, Chris (2015). Bitcoin for the Befuddled. No Starch Press. ISBN 978-1-59327-573-0.

- ↑ Popper, Nathaniel (19 December 2017). "How the Winklevoss Twins Found Vindication in a Bitcoin Fortune". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ↑ Alexander, Doug (15 February 2019). "Quadriga's late founder used to store clients' Bitcoin passwords on paper so they wouldn't get lost". Bloomberg News. Financial Post. Archived from the original on 20 June 2019. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Staff, Verge (13 December 2013). "Casascius, maker of shiny physical bitcoins, shut down by Treasury Department". The Verge. Archived from the original on 10 January 2014. Retrieved 10 January 2014.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 Ahonen, Elias; Rippon, Matthew J.; Kesselman, Howard (15 April 2016). Encyclopedia of Physical Bitcoins and Crypto-Currencies. ISBN 978-0-9950-8990-7.

- ↑ Mack, Eric (25 October 2011). "Are physical Bitcoins legal?". CNET. Archived from the original on 26 June 2019. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ↑ British Museum (2012). "Bitcoin token with digital code for bitcoin currency". Retrieved 17 May 2019.

- ↑ Roberts, Daniel (15 December 2017). "How to send bitcoin to a hardware wallet". Yahoo Finance. Archived from the original on 17 February 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2018.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNY2011 - ↑ Meola, Andrew (5 October 2017). "How distributed ledger technology will change the way the world works". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- ↑ Jerry Brito & Andrea Castillo (2013). "Bitcoin: A Primer for Policymakers" (PDF). Mercatus Center. George Mason University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2013. Retrieved 22 October 2013.

- ↑ Tschorsch, Florian; Scheuermann, Björn (2016). "Bitcoin and Beyond: A Technical Survey on Decentralized Digital Currencies". IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials. 18 (3): 2084–2123. doi:10.1109/comst.2016.2535718. S2CID 5115101.

- ↑ Beikverdi, A.; Song, J. (June 2015). Trend of centralization in Bitcoin's distributed network. pp. 1–6. doi:10.1109/SNPD.2015.7176229. ISBN 978-1-4799-8676-7. S2CID 15516195.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Gervais, Arthur; Karame, Ghassan O.; Capkun, Vedran; Capkun, Srdjan. "Is Bitcoin a Decentralized Currency?". InfoQ. InfoQ & IEEE Computer Society. Archived from the original on 10 October 2016. Retrieved 11 October 2016.

- ↑ Wilhelm, Alex. "Popular Bitcoin Mining Pool Promises To Restrict Its Compute Power To Prevent Feared '51%' Fiasco". TechCrunch. Archived from the original on 5 December 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ↑ Chan, Edwin. "China Plans to Ban Cryptocurrency Mining in Renewed Clampdown". www.bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on 18 December 2019. Retrieved 10 April 2019.

While China was once home to about 70 percent of Bitcoin mining and 90 percent of trades, authorities have waged a nearly two-year campaign to shrink the crypto industry amid concerns over speculative bubbles, fraud and wasteful energy consumption.

- ↑ Simonite, Tom (5 September 2013). "Mapping the Bitcoin Economy Could Reveal Users' Identities". MIT Technology Review. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ Lee, Timothy (21 August 2013). "Five surprising facts about Bitcoin". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 12 October 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ McMillan, Robert (6 June 2013). "How Bitcoin lets you spy on careless companies". Wired. Conde Nast. Archived from the original on 9 February 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2020.

- ↑ Ben-Sasson, Eli; Chiesa, Alessandro; Garman, Christina; Green, Matthew; Miers, Ian; Tromer, Eran; Virza, Madars (2014). "Zerocash: Decentralized Anonymous Payments from Bitcoin" (PDF). 2014 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy. IEEE computer society. Archived (PDF) from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ Möser, Malte; Böhme, Rainer; Breuker, Dominic (2013). An Inquiry into Money Laundering Tools in the Bitcoin Ecosystem (PDF). 2013 APWG eCrime Researchers Summit. IEEE. ISBN 978-1-4799-1158-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2019.