Urban planning

Urban planning, also known as regional planning, town planning, city planning, or rural planning, is a technical and political process that is focused on the development and design of land use and the built environment, including air, water, and the infrastructure passing into and out of urban areas, such as transportation, communications, and distribution networks and their accessibility.[1] Traditionally, urban planning followed a top-down approach in master planning the physical layout of human settlements.[2] The primary concern was the public welfare,[1][2] which included considerations of efficiency, sanitation, protection and use of the environment,[1] as well as effects of the master plans on the social and economic activities.[3] Over time, urban planning has adopted a focus on the social and environmental bottom-lines that focus on planning as a tool to improve the health and well-being of people while maintaining sustainability standards. Sustainable development was added as one of the main goals of all planning endeavors in the late 20th century when the detrimental economic and the environmental impacts of the previous models of planning had become apparent.[citation needed] Similarly, in the early 21st century, Jane Jacob's writings on legal and political perspectives to emphasize the interests of residents, businesses and communities effectively influenced urban planners to take into broader consideration of resident experiences and needs while planning.

Urban planning answers questions about how people will live, work and play in a given area and thus, guides orderly development in urban, suburban and rural areas.[4] Although predominantly concerned with the planning of settlements and communities, urban planners are also responsible for planning the efficient transportation of goods, resources, people and waste; the distribution of basic necessities such as water and electricity; a sense of inclusion and opportunity for people of all kinds, culture and needs; economic growth or business development; improving health and conserving areas of natural environmental significance that actively contributes to reduction in CO2 emissions[5] as well as protecting heritage structures and built environments. Urban planning is a dynamic field since the questions around how people live, work and play changes with time. These changes are constantly reflected in planning methodologies, zonal codes and policies making it a highly technical, political, social, economical and environmental field.

Urban planning is an interdisciplinary field that includes civil engineering, architecture, human geography, politics, social science and design sciences. Practitioners of urban planning are concerned with research and analysis, strategic thinking, Engineering architecture, urban design, public consultation, policy recommendations, implementation and management.[2] It is closely related to the field of urban design and some urban planners provide designs for streets, parks, buildings and other urban areas.[6] Urban planners work with the cognate fields of civil engineering, landscape architecture, architecture, and public administration to achieve strategic, policy and sustainability goals. Early urban planners were often members of these cognate fields though today, urban planning is a separate, independent professional discipline. The discipline of urban planning is the broader category that includes different sub-fields such as land-use planning, zoning, economic development, environmental planning, and transportation planning.[7] Creating the plans requires a thorough understanding of penal codes and zonal codes of planning.

Another important aspect of urban planning is that the range of urban planning projects include the large-scale master planning of empty sites or Greenfield projects as well as small-scale interventions and refurbishments of existing structures, buildings and public spaces. Pierre Charles L'Enfant in Washington DC, Daniel Burnham in Chicago and Georges-Eugene Haussmann in Paris planned cities from scratch, and Robert Moses and Le Corbusier refurbished and transformed cities and neighbourhoods to meet their ideas of urban planning.[8]

History

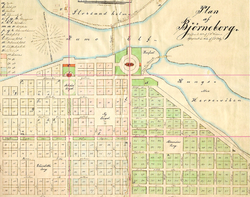

There is evidence of urban planning and designed communities dating back to the Mesopotamian, Indus Valley, Minoan, and Egyptian civilizations in the third millennium BCE. Archaeologists studying the ruins of cities in these areas find paved streets that were laid out at right angles in a grid pattern.[10] The idea of a planned out urban area evolved as different civilizations adopted it. Beginning in the 8th century BCE, Greek city states were primarily centered on orthogonal (or grid-like) plans.[11] The ancient Romans, inspired by the Greeks, also used orthogonal plans for their cities. City planning in the Roman world was developed for military defense and public convenience. The spread of the Roman Empire subsequently spread the ideas of urban planning. As the Roman Empire declined, these ideas slowly disappeared. However, many cities in Europe still held onto the planned Roman city center. Cities in Europe from the 9th to 14th centuries, often grew organically and sometimes chaotically. But in the following centuries with the coming of the Renaissance many new cities were enlarged with newly planned extensions.[12] From the 15th century on, much more is recorded of urban design and the people that were involved. In this period, theoretical treatises on architecture and urban planning start to appear in which theoretical questions around planning the main lines, ensuring plans meet the needs of the given population and so forth are addressed and designs of towns and cities are described and depicted. During the Enlightenment period, several European rulers ambitiously attempted to redesign capital cities. During the Second French Empire, Baron Georges-Eugène Haussmann, under the direction of Napoleon III, redesigned the city of Paris into a more modern capital, with long, straight, wide boulevards.[13]

Planning and architecture went through a paradigm shift at the turn of the 20th century. The industrialized cities of the 19th century grew at a tremendous rate. The evils of urban life for the working poor were becoming increasingly evident as a matter of public concern. The laissez-faire style of government management of the economy, in fashion for most of the Victorian era, was starting to give way to a New Liberalism that championed intervention on the part of the poor and disadvantaged. Around 1900, theorists began developing urban planning models to mitigate the consequences of the industrial age, by providing citizens, especially factory workers, with healthier environments. The following century would therefore be globally dominated by a central planning approach to urban planning, not necessarily representing an increment in the overall quality of the urban realm.

At the beginning of the 20th century, urban planning began to be recognized as a separate profession. The Town and Country Planning Association was founded in 1899 and the first academic course in Great Britain on urban planning was offered by the University of Liverpool in 1909.[14] In the 1920s, the ideas of modernism and uniformity began to surface in urban planning, and lasted until the 1970s. In 1933, Le Corbusier presented the Radiant City, a city that grows up in the form of towers, as a solution to the problem of pollution and over-crowding. But many planners started to believe that the ideas of modernism in urban planning led to higher crime rates and social problems.[3][15]

In the second half of the 20th century, urban planners gradually shifted their focus to individualism and diversity in urban centers.[16]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "What is Urban Planning". School of Urban Planning, McGill University. Archived from the original on 8 January 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Taylor, Nigel (1998). Urban Planning Theory Since 1945. Los Angeles: Sage. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-0-7619-6093-5.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Midgley, James (1999). Social Development: The Developmental Perspective in Social Welfare. Sage. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8039-7773-0.

- ↑ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 704. ISBN 978-0415862875.

- ↑ "3 urban planning trends that are changing how our cities will look in the future". Building Design + Construction. 18 February 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

- ↑ Van Assche, K., Beunen, R., Duineveld, M., & de Jong, H. (2013). Co-evolutions of planning and design: Risks and benefits of design perspectives in planning systems. Planning Theory, 12(2), 177-198.

- ↑ "What Is Planning?". American Planning Association. Archived from the original on 10 March 2015.

- ↑ "What is Urban Planning?". YouTube. Archived from the original on 30 October 2021.

- ↑ Hass-Klau, Carmen. "Motorization and Footpath Planning During the Third Reich." The Pedestrian and the City. Routledge, 2014.

- ↑ Davreu, Robert (1978). "Cities of Mystery: The Lost Empire of the Indus Valley". The World’s Last Mysteries. (second edition). Sydney: Readers’ Digest. pp. 121-129. ISBN 0-909486-61-1.

- ↑ Kolb, Frank (1984). Die Stadt im Altertum. München: Verlag C.H. Beck. pp. 51-141: Morris, A.E.J. (1972). History of Urban Form. Prehistory to the Renaissance. London. pp. 22-23.

- ↑ Boerefijn, Wim (2010). The foundation, planning and building of new towns in the 13th and 14th centuries in Europe. An architectural-historical research into urban form and its creation. Phd. thesis Universiteit van Amsterdam. ISBN 978-90-9025157-8.

- ↑ Jordan, David (1992). "Baron Haussmann and Modern Paris". American Scholar. 61 (1): 99.

- ↑ Fainstein, Susan S. Urban planning at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Morris, Eleanor Smith; et al. (1997). British Town Planning and Urban Design: Principles and policies. Harlow, Essex, England: Longman. pp. 147–149. ISBN 978-0-582-23496-3.

- ↑ Routley, Nick (20 January 2018). "The Evolution of Urban Planning". Visual Capitalist. Retrieved 25 September 2020.