Gupta–Hunnic Wars

Gupta–Hunnic Wars was a series of the wars between the Hunas (Hunnics) and the Gupta Empire.

| Gupta–Hunnic Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indo–Hunnic Wars | |||||||||

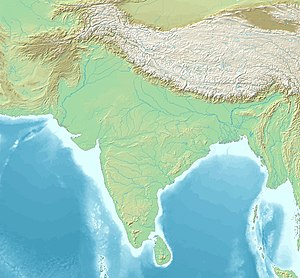

Approximate extent of the Alchon Huns, and find spots of inscriptions related to their local control (map of the Indian subcontinent)[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Maukhari dynasty Aulikara dynasty |

Sakas | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Yashodharman Prakashadharman Ishanavarman Mātṛviṣṇu † Kidara I |

3 unknown Hepthalite kings (POW) & Khingila I Piro Bhūta Bharatbala Toramana Mihirakula (POW) Prakasaditya Harigupta Dhanyavishnu | ||||||||

Background

Samudragupta's Āryāvarta campaigns

According to the Allahabad Pillar inscription, Samudragupta "forcibly uprooted" the following kings of Aryavarta, the northern region:[10]

- Rudradeva

- Matila

- Nagadatta

- Chandravarman

- Ganapatinaga

- Nagasena

- Achyuta-nandin

- Balavarman

Unlike the southern kings, the inscription does not mention the territories ruled by these kings, which suggests that their kingdoms were annexed to the Gupta empire.[11] The inscription also mentions that Samudragupta defeated some other kings, but does not mention their names, presumably because the poet saw them as unimportant.[10]

Rise of Kidara Kushans

The emergence of the Great Kushans in Bactria and Northwestern India during the first century A.D. transformed these regions into significant players in international politics. The Kushan empire posed a dual threat to the Parthians of Iran. Economically, the Kushans, like the Parthians, acted as intermediaries in trade. They controlled three crucial sections of the renowned Silk Road: firstly, the route connecting the Caspian and Euxine Seas; secondly, the path passing through Merv, Hecatompylos, and Ecbatana, crossing the Euphrates and reaching Mediterranean ports; and thirdly, the maritime route between India and the Red Sea, which gained immense importance after the discovery of monsoons. Consequently, they had the ability to redirect trade between China, India, and the eastern countries away from Parthian territory, posing a significant economic challenge to Parthian rulers.[12]

The political implications of the Kushans' rise as a major power were also profound for Iran. Instead of facing a single enemy in the West, Iran found itself sandwiched between the Roman Empire and the Kushans. The Romans, who were constantly engaged in rivalry and conflict with the Parthians, recognized the strategic importance of this empire and sought direct relations with its rulers to safeguard trade routes between Rome, China, and India. Caught between these two powers, the early Sasanians, who succeeded the Parthians as the imperial rulers of Iran in 224 A.D., made the conquest of the Kushan empire their primary objective in Eastern policy, and they achieved remarkable success in this endeavor. The first Sasanian emperor, Ardashir I (224-241 A.D.), conquered Kushan principalities to the north of the Hindukush. Although Kushan chiefs continued to govern these territories, they had to accept the overlordship of the Sasanian emperor.[12]

Submission of Kidarites (Little Kushans)

The Kushan Empire continued as a remnant known as the "Little Kushans", based in the Punjab. Around 270 their territories on the Gangetic plain became independent under local dynasties such as the Yaudheyas. Then in the mid-4th century they were subjugated by the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta.[13] In his inscription on the Allahabad pillar Samudragupta proclaims that the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi (referring to the last Kushan rulers, being a deformation of the Kushan regnal titles Devaputra, Shao and Shaonanoshao: "Son of God, King, King of Kings") are now under his dominion, and that they were forced to "self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces".[14][13][15] This suggests that by the time of the Allahabad inscription the Kushans still ruled in Punjab, but under the suzerainty of the Gupta Emperor.[13]

North-western policy of Samudragupta

The reconstruction of Samudragupta's northwest policy mentioned earlier aligns with other intriguing facts. In 361 AD, an Indian delegation reportedly visited Rome, as stated by Roman historians. Despite having been dispatched from India earlier, the embassy did not reach Rome until 351 AD. Taking into account the political circumstances in India during the mid-4th century AD, this fact holds significant value. Before the year 361 AD, it was noted that the Roman emperors were engaged in a conflict with the Sassanids. Hence, it was not unexpected for Samudragupta to try to stop future conflicts with the Persian army on the Western Front by allying with Kidara I against Shahpur II. Hence, it is possible that he dispatched an embassy to Rome prior to 361 AD.[18]

Additionally, considering the political background of Bactria and north-west India described earlier, it is more probable that Kalidasa authored the Digvijaya story of Raghu using the real events resulting from Samudragupta's conquest, assuming great force. Kalidasa stated that Raghu conquered the Deccan's Trikutas before heading overland to conquer the Parasikas. Having emerged victorious over them, he went on to conquer the Hunas before launching an assault on the Kambojas. The Parasikas mentioned by Kalidasa are evidently related to the Sasanians. He mentioned that the Hunas resided by the Vankshu or Oxus river. During the third quarter of the fourth century AD, this was exactly the area where they resided. Ultimately, it may be concluded that the Kambojas of Raghuvamsa are likely to be the same as Kidara Kushans, as historical evidence shows that Kidara Inot only conquered Gandhara but also the five neighboring kingdoms, of course which were in Kambojas.[18]

Gupta-Kidara alliance

The Kushan contemporary of Samudragupta, was Kidāra. He was initially a part of the Great Kushan family. It was after him that his individuals got to be celebrated as the small Kushans. Hence, it can be promptly conceded that he was known to his counterparts as a ruler of the Devaputra family. But he was not effective enough to utilize the title Shahanushahi. He was simply a Shahi. His coins bearing the legend 'Kidāra Kushāṇa Shāhi' proved it. Subsequently, he can be effectively recognized with Daivaputrashāhi of the Allahabad pillar inscription. Here it is curiously to note that opposite to the for the most part acknowledged see, within the Prayaga Prasasti the word Devaputra has not been utilized as a title, for the reality that it has been utilized in its taddhita shape not simply appears that it must be taken in conjunction with the another word 'Shāhi', it moreover demonstrates that the compound Daivaputrashahi would connote 'Shāhi, who had a place to (the family of) the Devaputras'. As respects Kidāra's contemporary Shahanushahi, he might have been no other than Shapur II, the Sassanian Shahanshah. On the premise of this proposal the course of history of Bactria and North-Western India may be reproduced as takes after:

Kidara, after having set up himself in Gandhara, apparently at the cost of the Saka rulers, drew closer to Samudragupta a few times after 359 A. D., sent him presents and callings of steadfastness and inquired for his offer of assistance against the Sasanians. Samudragupta, on his part, was exceptionally much on edge to amplify his circle of impact past the central Punjab where his subordinate partners, the Gadaharas, were administering. He saw with uneasiness the tribal developments which were taking place in that heading and were posturing a risk to his recently established domain. But he was not a vanquisher, he was a statesman as well. He knew he possessed impediments and had the intelligence of restoring the prevailed rulers of the South.[21]

He needed to be included in a North-Western experience, indeed less. But, in any case, he was anxious to make the wildernesses of the domain and the western trade-routes secure and secure. He subsequently, did what was the most excellent; beneath the circumstances he concluded an alliance with Kidara and as the more grounded part of the association gave him an offer of assistance against Shapur II. His arrangement was prominently effective and Kidara vanquished the Sasanians twice in 367-68 A. D. It may not suggest that Shapur II got to be a vassal of Kidara or Samudragupta. But it does indicate that the articulation of Harishena about the connection of his master with the Sasanian ruler ought to not be suggested as through and through altogether without foundation.[21]

First Hephthalite invasion

Kidara, thereafter the year 367-68 A. D., likely in c. 370 A. D. had to bargain with the attack of the Jouan-Jouan or Hiung-nu or the White Huns from Bactria or Valhika. He put his son within the charge of his capital and went towards west to meet the intruders. This time too, Samudragupta shows up to have given considerable assistance to his Kushan ally. As a matter of truth, the victory of Kidara against the Hunas, whom he seem not check prior when he was in Bactria, demonstrates that this time he had an effective partner on his side. In this way, a fruitful endeavor by the Gupta sovereign in c. 370 A. D. against the Valhikas 'across the seven mouths of the river Indus' gets to be a really solid plausibility. It is one of the reasons which have driven us to hypothesize the identicality of the lord 'Chandra' with Samudragupta. It may, in any case, be recollected that the history of Bactria and the North-Western India as laid out over does not depend upon the recognizable proof of Samudragupta with the ruler of the Meharauli inscription. For example, in case we are to incline toward the hypothesis of the distinguishing proof of Chandragupta II with the ruler of this record, we can assume that it was Chandragupta, the offspring of Samudragupta, was the one sent as the pioneer of this expedition.[22]

Geographical factors in North-western policy

The general station of the ancient conglomerate-builders of the Ganga Valley towards the North-West was conditioned by the interplay of several factors. Geographically, the Indus valley is the western of cornucopia of what may be called the Fertile Crescent of India, and gives the print that it's nearly connected with the Ganga Valley. But there's another side of this picture also. It may be noted and needs to be emphasized that the Indus river-system is not only unconnected with any other river of North India, but it's indeed separated from the rest of the country by the vast desert of Thar. The stretch of the home which connects it with the Ganga Valley viz.[25]

The Thanesar-Delhi-Kurukshetra division–roughly the ancient realm of the Kuru Kingdom-is veritably narrow and communication through it was rendered delicate in the ancient times by the great timbers, similar as the Khandava, Kāmākhyā, Kurujāngala and Dvaitavana and also by a large number of small gutters. These walls, it seems, rendered the subjection of the Indus receptacle by the powers of the Ganga Valley relatively delicate and made these two regions to appear more distant and remote from each other than they actually were. It's a literal fact that with the exception of the Mauryas, nearly all the conglomerate-builders of the Ganga Valley the Nandas, the Sungas, the Nagas, the Guptas and indeed the Vardhanas noway seriously tried to conquer the region to the west of the Divide.[25]

It doesn't mean that they noway took any interest in the political fortunes of the Indus receptacle; they couldn't go to neglect it altogether. piecemeal from the fact that this region also belonged to the larger Indian world and, thus, the achievement of universal sovereignty (chakravartitra) was regarded as deficient without establishing some kind of suzerainty over it, they could hardly forget that utmost of the routes of the Indian trade with the Western countries were controlled by the North-Western powers. Above all, the nearly constant affluence via the Indus receptacle of Central and Western Asiatic peoples who relatively constantly hovered the security of the antarvedi itself, impelled them to take note of the political developments in the Indus receptacle. But these lodestones weren't sufficient enough to bait them to take over wars of subjection in that region.[25]

The Vardhanas, though a power of Thanesar, were interested in it only to the extent of transferring occasional peregrinations against the Hunas; the Sungas communicated some interest only when they were hovered by the Bactrian Greeks; indeed the Mauryan subjection of this region was maybe the result of the fact that Chandragupta Maurya started his political career there and the irruptions of Alexander and Seleucus had rendered its objectification in the conglomerate necessary. In the early mediaeval period also, the Rajput autocrats of the Ganga receptacle generally communicated interest in the politics of the Indus Valley states only when they were themselves hovered by the raiders coming from that direction. Prithviraja III, the Chahamanas of Shakambhari king of Delhi, for illustration, took no notice of the expansion of the Ghurid area in the Punjab till his own security was hovered and indeed after achieving palm in the first battle of Tarain he took no suitable way to oust the Muslims from the Punjab; he was putatively more interested in the politics of the antarvedi.[26]

In the light of the below discussion, the station of the Guptas towards the Indus Valley becomes comprehensible,

Notes

- ↑ " The Mehrauli Pillar Inscription (No.20) describes the digvijaya of a king named Candra (i.e. Candragupta II) in the first verse as stated below :

"He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries, he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against him;—he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vāhlikas;—he by the breezes of whose prowess the Southern ocean is even still perfumed".

We find various readings of the name Vāhlika in literature which are : Vāhlika, Bāhlika, Vāhlīka and Bāhlīka. In our inscription (No. 20) 'Vāhilikāḥ', i.e. Bactria (modern Balkh) region on the Oxus in the northern part of Afghanistan."[6]

- ↑ J. F. Fleet's 1888 translation is as follows:[7]

(Verse 1) He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries (Bengal), he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against (him); – he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vahlikas were conquered; – he, by the breezes of whose prowess the southern ocean is even still perfumed; –

- ↑ "THE SECOND HUNA INVASION

The attitude of the imperial Guptas towards the North-West presents a very interesting problem for the students of their history. It is quite apparent that they had the power and resources to incorporate the Indus basin in their empire ; but they did nothing more than imposing a vague sort of suzerainty over it which did not last very long."[8]

Reference

- ↑ Hans Bakker 24th Gonda lecture

- ↑ Bakker 2020, pp. 31–34.

- ↑ Bakker 2020, p. 34.

- ↑ Majumdar, R. C., ed. (1970). History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume 03, The Classical Age. Public Resource. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 38.

- ↑ History Of The Imperial Guptas. p. 350.

- ↑ Tej Ram Sharma 1978, p. 167.

- ↑ Balasubramaniam 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, p. 277.

- ↑ "The young son of Mahendrasena led his father's army of two hundred thousand men against the enemy whose soldiers numbered three hundred thousand. The prince however, broke the enemy army and won the battle. On his return his father crown him saying "henceforth rule the kingdom," and himself retired to religious life. For twelve years after this, the new king fought these foreign enemies, and ultimately captured and executed the three kings.' It has been suggested that this story gives an account of the fight between Skandagupta and the Hūṇas (IHIJ. 36)." The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age. G. Allen & Unwin. 1951. p. 27.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Agrawal 1989, p. 114.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 22.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Goyal 1967, p. 169.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Dani, Litvinsky & Zamir Safi 1996, pp. 165–166

- ↑ Lines 23-24 of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta: "Self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces through the Garuḍa badge, by the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi and the Śaka lords and by (rulers) occupying all Island countries, such as Siṁhala and others."

- ↑ Cribb, Joe; Singh, Karan (Winter 2017). "Two Curious Kidarite Coin Types From 3rd Century Kashmir". JONS. 230: 3.

- ↑ A similar coin with reading of the legend

- ↑ Lerner, Judith A. (210). Observations on the Typology and Style of Seals and Sealings from Bactria and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands, in Coins, Art and Chronology II. The First Millennium CE in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Vienna: ÖAW. p. 246, note 7.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goyal 1967, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284sq

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Iranica, article Kidarites: "On Gandhāran coins bearing their name the ruler is always clean-shaven, a fashion more typical of Altaic people than of Iranians" in "KIDARITES – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Goyal 1967, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ KURBANOV, AYDOGDY (2010). THE HEPHTHALITES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS (PDF). Berlin: Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Free University. p. 39.

- ↑ Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-933079-9.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Goyal 1967, pp. 280-281.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 278-280.