City

A city is a large human settlement.[1][2][lower-alpha 1] It can be defined as a permanent and densely settled place with administratively defined boundaries whose members work primarily on non-agricultural tasks.[3] Cities generally have extensive systems for housing, transportation, sanitation, utilities, land use, production of goods, and communication. Their density facilitates interaction between people, government organisations and businesses, sometimes benefiting different parties in the process, such as improving efficiency of goods and service distribution.

Historically, city-dwellers have been a small proportion of humanity overall, but following two centuries of unprecedented and rapid urbanization, more than half of the world population now lives in cities, which has had profound consequences for global sustainability.[4][5] Present-day cities usually form the core of larger metropolitan areas and urban areas—creating numerous commuters traveling towards city centres for employment, entertainment, and education. However, in a world of intensifying globalisation, all cities are to varying degrees also connected globally beyond these regions. This increased influence means that cities also have significant influences on global issues, such as sustainable development, global warming and global health. Because of these major influences on global issues, the international community has prioritized investment in sustainable cities through Sustainable Development Goal 11. Due to the efficiency of transportation and the smaller land consumption, dense cities hold the potential to have a smaller ecological footprint per inhabitant than more sparsely populated areas.[6] Therefore, compact cities are often referred to as a crucial element of fighting climate change.[7] However, this concentration can also have significant negative consequences, such as forming urban heat islands, concentrating pollution, and stressing water supplies and other resources.

Other important traits of cities besides population include the capital status and relative continued occupation of the city. For example, country capitals such as Beijing, London, Mexico City, Moscow, Nairobi, New Delhi, Paris, Rome, Athens, Seoul, Singapore, Tokyo, and Washington, D.C. reflect the identity and apex of their respective nations.[8] Some historic capitals, such as Kyoto and Xi'an, maintain their reflection of cultural identity even without modern capital status. Religious holy sites offer another example of capital status within a religion, Jerusalem, Mecca, Varanasi, Ayodhya, Haridwar and Allahabad each hold significance.

Meaning

A city can be distinguished from other human settlements by its relatively great size, but also by its functions and its special symbolic status, which may be conferred by a central authority. The term can also refer either to the physical streets and buildings of the city or to the collection of people who dwell there, and can be used in a general sense to mean urban rather than rural territory.[10][11]

National censuses use a variety of definitions - invoking factors such as population, population density, number of dwellings, economic function, and infrastructure - to classify populations as urban. Typical working definitions for small-city populations start at around 100,000 people.[12] Common population definitions for an urban area (city or town) range between 1,500 and 50,000 people, with most U.S. states using a minimum between 1,500 and 5,000 inhabitants.[13][14] Some jurisdictions set no such minima.[15] In the United Kingdom, city status is awarded by the Crown and then remains permanently. (Historically, the qualifying factor was the presence of a cathedral, resulting in some very small cities such as Wells, with a population 12,000 as of 2018[update] and St Davids, with a population of 1,841 as of 2011[update].) According to the "functional definition", a city is not distinguished by size alone, but also by the role it plays within a larger political context. Cities serve as administrative, commercial, religious, and cultural hubs for their larger surrounding areas.[16][17] An example of a settlement with "city" in their names which may not meet any of the traditional criteria to be named such include Broad Top City, Pennsylvania (population 452).

The presence of a literate elite is sometimes included[by whom?] in the definition.[18] A typical city has professional administrators, regulations, and some form of taxation (food and other necessities or means to trade for them) to support the government workers. (This arrangement contrasts with the more typically horizontal relationships in a tribe or village accomplishing common goals through informal agreements between neighbors, or through leadership of a chief.) The governments may be based on heredity, religion, military power, work systems such as canal-building, food-distribution, land-ownership, agriculture, commerce, manufacturing, finance, or a combination of these. Societies that live in cities are often called civilizations.

The degree of urbanization is a modern metric to help define what comprises a city: "a population of at least 50,000 inhabitants in contiguous dense grid cells (>1,500 inhabitants per square kilometer)".[19] This metric was "devised over years by the European Commission, OECD, World Bank and others, and endorsed in March [2021] by the United Nations... largely for the purpose of international statistical comparison".[20]

Etymology

The word city and the related civilization come from the Latin root civitas, originally meaning 'citizenship' or 'community member' and eventually coming to correspond with urbs, meaning 'city' in a more physical sense.[10] The Roman civitas was closely linked with the Greek polis—another common root appearing in English words such as metropolis.[21]

In toponymic terminology, names of individual cities and towns are called astionyms (from Ancient Greek ἄστυ 'city or town' and ὄνομα 'name').[22]

Geography

Urban geography deals both with cities in their larger context and with their internal structure.[23] Cities are estimated to cover about 3% of the land surface of the Earth.[24]

Site

Town siting has varied through history according to natural, technological, economic, and military contexts. Access to water has long been a major factor in city placement and growth, and despite exceptions enabled by the advent of rail transport in the nineteenth century, through the present most of the world's urban population lives near the coast or on a river.[25]

Urban areas as a rule cannot produce their own food and therefore must develop some relationship with a hinterland which sustains them.[26] Only in special cases such as mining towns which play a vital role in long-distance trade, are cities disconnected from the countryside which feeds them.[27] Thus, centrality within a productive region influences siting, as economic forces would in theory favor the creation of market places in optimal mutually reachable locations.[28]

Center

The vast majority of cities have a central area containing buildings with special economic, political, and religious significance. Archaeologists refer to this area by the Greek term temenos or if fortified as a citadel.[29] These spaces historically reflect and amplify the city's centrality and importance to its wider sphere of influence.[28] Today cities have a city center or downtown, sometimes coincident with a central business district.

Public space

Cities typically have public spaces where anyone can go. These include privately owned spaces open to the public as well as forms of public land such as public domain and the commons. Western philosophy since the time of the Greek agora has considered physical public space as the substrate of the symbolic public sphere.[30][31] Public art adorns (or disfigures) public spaces. Parks and other natural sites within cities provide residents with relief from the hardness and regularity of typical built environments.

Internal structure

Urban structure generally follows one or more basic patterns: geomorphic, radial, concentric, rectilinear, and curvilinear. Physical environment generally constrains the form in which a city is built. If located on a mountainside, urban structure may rely on terraces and winding roads. It may be adapted to its means of subsistence (e.g. agriculture or fishing). And it may be set up for optimal defense given the surrounding landscape.[33] Beyond these "geomorphic" features, cities can develop internal patterns, due to natural growth or to city planning.

In a radial structure, main roads converge on a central point. This form could evolve from successive growth over a long time, with concentric traces of town walls and citadels marking older city boundaries. In more recent history, such forms were supplemented by ring roads moving traffic around the outskirts of a town. Dutch cities such as Amsterdam and Haarlem are structured as a central square surrounded by concentric canals marking every expansion. In cities such as Moscow, this pattern is still clearly visible.

A system of rectilinear city streets and land plots, known as the grid plan, has been used for millennia in Asia, Europe, and the Americas. The Indus Valley Civilisation built Mohenjo-Daro, Harappa and other cities on a grid pattern, using ancient principles described by Kautilya, and aligned with the compass points.[34][16][35][36] The ancient Greek city of Priene exemplifies a grid plan with specialized districts used across the Hellenistic Mediterranean.

Urban areas

Urban-type settlement extends far beyond the traditional boundaries of the city proper[39] in a form of development sometimes described critically as urban sprawl.[40] Decentralization and dispersal of city functions (commercial, industrial, residential, cultural, political) has transformed the very meaning of the term and has challenged geographers seeking to classify territories according to an urban-rural binary.[14]

Metropolitan areas include suburbs and exurbs organized around the needs of commuters, and sometimes edge cities characterized by a degree of economic and political independence. (In the US these are grouped into metropolitan statistical areas for purposes of demography and marketing.) Some cities are now part of a continuous urban landscape called urban agglomeration, conurbation, or megalopolis (exemplified by the BosWash corridor of the Northeastern United States.)[41]

History

The cities of Jericho, Aleppo, Faiyum, Yerevan, Athens, Damascus and Argos are among those laying claim to the longest continual inhabitation.

Cities, characterized by population density, symbolic function, and urban planning, have existed for thousands of years.[42] In the conventional view, civilization and the city both followed from the development of agriculture, which enabled production of surplus food, and thus a social division of labour (with concomitant social stratification) and trade.[43][44] Early cities often featured granaries, sometimes within a temple.[45] A minority viewpoint considers that cities may have arisen without agriculture, due to alternative means of subsistence (fishing),[46] to use as communal seasonal shelters,[47] to their value as bases for defensive and offensive military organization,[48][49] or to their inherent economic function.[50][51][52] Cities played a crucial role in the establishment of political power over an area, and ancient leaders such as Alexander the Great founded and created them with zeal.[53]

Ancient times

Jericho and Çatalhöyük, dated to the eighth millennium BC, are among the earliest proto-cities known to archaeologists.[47][54] While the Mesopotamian city of Uruk (ancient Iraq), from the mid 4th millennia BCE, is considered by some, the first true City, with its name attributed, the Uruk period, to the era.[55][56][57]

In the fourth and third millennium BC, complex civilizations flourished in the river valleys of Mesopotamia, India, China, and Egypt.[58][59] Excavations in these areas have found the ruins of cities geared variously towards trade, politics, or religion. Some had large, dense populations, but others carried out urban activities in the realms of politics or religion without having large associated populations.

Among the early Old World cities, Mohenjo-daro of the Indus Valley Civilization in present-day Pakistan, existing from about 2600 BC, was one of the largest, with a population of 50,000 or more and a sophisticated sanitation system.[60] China's planned cities were constructed according to sacred principles to act as celestial microcosms.[61]

The Ancient Egyptian cities known physically by archaeologists are not extensive.[16] They include (known by their Arab names) El Lahun, a workers' town associated with the pyramid of Senusret II, and the religious city Amarna built by Akhenaten and abandoned. These sites appear planned in a highly regimented and stratified fashion, with a minimalistic grid of rooms for the workers and increasingly more elaborate housing available for higher classes.[62]

In Mesopotamia, the civilization of Sumer, followed by Assyria and Babylon, gave rise to numerous cities, governed by kings and fostering multiple languages written in cuneiform.[63] The Phoenician trading empire, flourishing around the turn of the first millennium BC, encompassed numerous cities extending from Tyre, Cydon, and Byblos to Carthage and Cádiz.

In the following centuries, independent city-states of Greece, especially Athens, developed the polis, an association of male landowning citizens who collectively constituted the city.[64] The agora, meaning "gathering place" or "assembly", was the center of athletic, artistic, spiritual and political life of the polis.[65] Rome was the first city that surpassed one million inhabitants. Under the authority of its empire, Rome transformed and founded many cities (coloniae), and with them brought its principles of urban architecture, design, and society.[66]

In the ancient Americas, early urban traditions developed in the Andes and Mesoamerica. In the Andes, the first urban centers developed in the Norte Chico civilization, Chavin and Moche cultures, followed by major cities in the Huari, Chimu and Inca cultures. The Norte Chico civilization included as many as 30 major population centers in what is now the Norte Chico region of north-central coastal Peru. It is the oldest known civilization in the Americas, flourishing between the 30th century BC and the 18th century BC.[67] Mesoamerica saw the rise of early urbanism in several cultural regions, beginning with the Olmec and spreading to the Preclassic Maya, the Zapotec of Oaxaca, and Teotihuacan in central Mexico. Later cultures such as the Aztec, Andean civilization, Mayan, Mississippians, and Pueblo peoples drew on these earlier urban traditions. Many of their ancient cities continue to be inhabited, including major metropolitan cities such as Mexico City, in the same location as Tenochtitlan; while ancient continuously inhabited Pueblos are near modern urban areas in New Mexico, such as Acoma Pueblo near the Albuquerque metropolitan area and Taos Pueblo near Taos; while others like Lima are located nearby ancient Peruvian sites such as Pachacamac.

Jenné-Jeno, located in present-day Mali and dating to the third century BC, lacked monumental architecture and a distinctive elite social class—but nevertheless had specialized production and relations with a hinterland.[68] Pre-Arabic trade contacts probably existed between Jenné-Jeno and North Africa.[69] Other early urban centers in sub-Saharan Africa, dated to around 500 AD, include Awdaghust, Kumbi-Saleh the ancient capital of Ghana, and Maranda a center located on a trade route between Egypt and Gao.[70]

Middle Ages

In the remnants of the Roman Empire, cities of late antiquity gained independence but soon lost population and importance. The locus of power in the West shifted to Constantinople and to the ascendant Islamic civilization with its major cities Baghdad, Cairo, and Córdoba.[71] From the 9th through the end of the 12th century, Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, was the largest and wealthiest city in Europe, with a population approaching 1 million.[72][73] The Ottoman Empire gradually gained control over many cities in the Mediterranean area, including Constantinople in 1453.

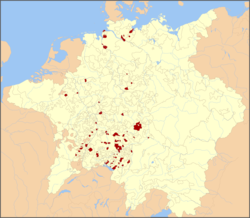

In the Holy Roman Empire, beginning in the 12th. century, free imperial cities such as Nuremberg, Strasbourg, Frankfurt, Basel, Zurich, Nijmegen became a privileged elite among towns having won self-governance from their local lay or secular lord or having been granted self-governanace by the emperor and being placed under his immediate protection. By 1480, these cities, as far as still part of the empire, became part of the Imperial Estates governing the empire with the emperor through the Imperial Diet.[74]

By the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, some cities become powerful states, taking surrounding areas under their control or establishing extensive maritime empires. In Italy medieval communes developed into city-states including the Republic of Venice and the Republic of Genoa. In Northern Europe, cities including Lübeck and Bruges formed the Hanseatic League for collective defense and commerce. Their power was later challenged and eclipsed by the Dutch commercial cities of Ghent, Ypres, and Amsterdam.[75] Similar phenomena existed elsewhere, as in the case of Sakai, which enjoyed a considerable autonomy in late medieval Japan.

In the first millennium AD, the Khmer capital of Angkor in Cambodia grew into the most extensive preindustrial settlement in the world by area,[76][77] covering over 1,000 sq km and possibly supporting up to one million people.[76][78]

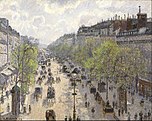

Early modern

In the West, nation-states became the dominant unit of political organization following the Peace of Westphalia in the seventeenth century.[79][80] Western Europe's larger capitals (London and Paris) benefited from the growth of commerce following the emergence of an Atlantic trade. However, most towns remained small.

During the Spanish colonization of the Americas the old Roman city concept was extensively used. Cities were founded in the middle of the newly conquered territories, and were bound to several laws regarding administration, finances and urbanism.

Industrial age

The growth of modern industry from the late 18th century onward led to massive urbanization and the rise of new great cities, first in Europe and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas.

England led the way as London became the capital of a world empire and cities across the country grew in locations strategic for manufacturing.[81] In the United States from 1860 to 1910, the introduction of railroads reduced transportation costs, and large manufacturing centers began to emerge, fueling migration from rural to city areas.

Industrialized cities became deadly places to live, due to health problems resulting from overcrowding, occupational hazards of industry, contaminated water and air, poor sanitation, and communicable diseases such as typhoid and cholera. Factories and slums emerged as regular features of the urban landscape.[82]

Post-industrial age

In the second half of the twentieth century, deindustrialization (or "economic restructuring") in the West led to poverty, homelessness, and urban decay in formerly prosperous cities. America's "Steel Belt" became a "Rust Belt" and cities such as Detroit, Michigan, and Gary, Indiana began to shrink, contrary to the global trend of massive urban expansion.[83] Such cities have shifted with varying success into the service economy and public-private partnerships, with concomitant gentrification, uneven revitalization efforts, and selective cultural development.[84] Under the Great Leap Forward and subsequent five-year plans continuing today, the People's Republic of China has undergone concomitant urbanization and industrialization and to become the world's leading manufacturer.[85][86]

Amidst these economic changes, high technology and instantaneous telecommunication enable select cities to become centers of the knowledge economy.[87][88][89] A new smart city paradigm, supported by institutions such as the RAND Corporation and IBM, is bringing computerized surveillance, data analysis, and governance to bear on cities and city-dwellers.[90] Some companies are building brand new masterplanned cities from scratch on greenfield sites.

- ↑ Goodall, B. (1987) The Penguin Dictionary of Human Geography. London: Penguin.

- ↑ Kuper, A. and Kuper, J., eds (1996) The Social Science Encyclopedia. 2nd edition. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Caves, R. W. (2004). Encyclopedia of the City. Routledge. p. 99.

- ↑ Ritchie, Hannah; Roser, Max (13 June 2018). "Urbanization". Our World in Data. Retrieved 14 February 2021.

- ↑ James, Paul; with Magee, Liam; Scerri, Andy; Steger, Manfred B. (2015). Urban Sustainability in Theory and Practice: Circles of Sustainability. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781315765747.

- ↑ "Cities: a 'cause of and solution to' climate change". UN News. 18 September 2019. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "Sustainable cities must be compact and high-density". The Guardian News. 30 June 2011. Retrieved 20 March 2021.

- ↑ "Ch2". www-personal.umich.edu. Retrieved 10 May 2021.

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy (1968), p. 45.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 "city, n.", Oxford English Dictionary, June 2014.

- ↑ Kevin A. Lynch, "What Is the Form of a City, and How is It Made?"; in Marzluff et al. (2008), p. 678. "The city may be looked on as a story, a pattern of relations between human groups, a production and distribution space, a field of physical force, a set of linked decisions, or an arena of conflict. Values are embedded in these metaphors: historic continuity, stable equilibrium, productive efficiency, capable decision and management, maximum interaction, or the progress of political struggle. Certain actors become the decisive elements of transformation in each view: political leaders, families and ethnic groups, major investors, the technicians of transport, the decision elite, the revolutionary classes."

- ↑ "Population by region - Urban population by city size - OECD Data". theOECD. Retrieved 3 June 2019.

- ↑ "Table 6" in United Nations Demographic Yearbook (2015), the 1988 version of which is quoted in Carter (1995), pp. 10–12.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHugoEtAl2003 - ↑ "How NC Municipalities Work – North Carolina League of Municipalities". www.nclm.org. Archived from the original on 16 May 2010.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Smith, "Earliest Cities", in Gmelch & Zenner (2002).

- ↑ Marshall (1989), pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Lewis Dijkstra, Ellen Hamilton, Somik Lall, and Sameh Wahba (10 March 2020). "How do we define cities, towns, and rural areas?".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Moore, Oliver (2 October 2021). "What makes a city a city? It's a little complicated". The Globe and Mail. p. A11.

- ↑ Yi Jianping, "'Civilization' and 'State': An Etymological Perspective"; Social Sciences in China 33(2), 2012; doi:10.1080/02529203.2012.677292.

- ↑ Room 1996, p. 13.

- ↑ Carter (1995), pp. 5–7. "[...] the two main themes of study introduced at the outset: the town as a distributed feature and the town as a feature with internal structure, or in other words, the town in area and the town as area."

- ↑ Bataille, L., "From passive to energy generating assets", Energy in Buildings & Industry, October 2021, p. 34, accessed 12 February 2022

- ↑ Marshall (1989), pp. 11–14.

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 155–156.

- ↑ Marshall (1989), p. 15. "The mutual interdependence of town and country has one consequence so obvious that it is easily overlooked: at the global scale, cities are generally confined to areas capable of supporting a permanent agricultural population. Moreover, within any area possessing a broadly uniform level of agricultural productivity, there is a rough but definite association between the density of the rural population and the average spacing of cities above any chosen minimum size."

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Latham et al. (2009), p. 18. "From the simplest forms of exchange, when peasant farmers literally brought their produce from the fields into the densest point of interaction—giving us market towns—the significance of central places to surrounding territories began to be asserted. As cities grew in complexity, the major civic institutions, from seats of government to religious buildings, would also come to dominate these points of convergence. Large central squares or open spaces reflected the importance of collective gatherings in city life, such as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, the Zócalo in Mexico City, the Piazza Navonae in Rome and Trafalgar Square in London.

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 34–35. "In the center of the city, an elite compound or temenos was situated. Study of the very earliest cities show this compound to be largely composed of a temple and supporting structures. The temple rose some 40 feet above the ground and would have presented a formidable profile to those far away. The temple contained the priestly class, scribes, and record keepers, as well as granaries, schools, crafts—almost all non-agricultural aspects of society.

- ↑ Latham et al. (2009), pp. 177–179.

- ↑ Don Mitchell, "The End of Public Space? People's Park, Definitions of the Public, and Democracy";[permanent dead link] Annals of the Association of American Geographers 85(1), March 1995.

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy (1986), pp. 146–148.

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy (1968), 21–33.

- ↑ Mohan Pant and Shjui Fumo, "The Grid and Modular Measures in The Town Planning of Mohenjodaro and Kathmandu Valley: A Study on Modular Measures in Block and Plot Divisions in the Planning of Mohenjodaro and Sirkap (Pakistan), and Thimi (Kathmandu Valley)"; Journal of Asian Architecture and Building Engineering 59, May 2005.

- ↑ Michel Danino, "New Insights into Harappan Town-Planning, Proportions and Units, with Special Reference to Dholavira Archived 25 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine", "Man and Environment 33(1), 2008.

- ↑ Jane McIntosh, The Ancient Indus Valley: New Perspectives; ABC-CLIO, 2008; ISBN 978-1-57607-907-2 pp. 231, 346.

- ↑ Volker M. Welter, "The 1925 Master Plan for Tel-Aviv by Patrick Geddes"; Israel Studies 14(3), Fall 2009.

- ↑ Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, "Locations, Population and Density per Sq. km., by metropolitan area and selected localities, 2015 Archived 2016-10-02 at the Wayback Machine."

- ↑ Carter (1995), p. 15. "In the underbound city the administratively defined area is smaller than the physical extent of settlement. In the overbound city the administrative area is greater than the physical extent. The 'truebound' city is one where the administrative bound is nearly coincidental with the physical extent."

- ↑ Paul James; Meg Holden; Mary Lewin; Lyndsay Neilson; Christine Oakley; Art Truter; David Wilmoth (2013). "Managing Metropolises by Negotiating Mega-Urban Growth". In Harald Mieg; Klaus Töpfer (eds.). Institutional and Social Innovation for Sustainable Urban Development. Routledge.

- ↑ Chaunglin Fang & Danlin Yu, "Urban agglomeration: An evolving concept of an emerging phenomenon"; Landscape and Urban Planning 162, 2017.

- ↑ Nick Compton, "What is the oldest city in the world?", The Guardian, 16 February 2015.

- ↑ (Bairoch 1988, pp. 3–4)

- ↑ (Pacione 2001, p. 16)

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), p. 26. "Early cities also reflected these preconditions in that they served as places where agricultural surpluses were stored and distributed. Cities functioned economically as centers of extraction and redistribution from countryside to granaries to the urban population. One of the main functions of this central authority was to extract, store, and redistribute the grain. It is no accident that granaries—storage areas for grain—were often found within the temples of early cities."

- ↑ Jennifer R. Pournelle, "KLM to CORONA: A Bird's Eye View of Cultural Ecology and Early Mesopotamian Urbanization"; in Settlement and Society: Essays Dedicated to Robert McCormick Adams ed. Elizabeth C. Stone; Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCLA, and Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago, 2007.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Fredy Perlman, Against His-Story, Against Leviathan, Detroit: Black & Red, 1983; p. 16.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMumfurd1961war - ↑ Ashworth (1991), pp. 12–13.

- ↑ (Jacobs 1969, p. 23)

- ↑ P.J. Taylor, "Extraordinary Cities I: Early 'City-ness' and the Invention of Agriculture"; International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36(3), 2012; doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01101.x; see also GaWC Research Bulletins 359 and 360.

- ↑ Michael E. Smith, Jason Ur, & Gary M. Feinman, "Jane Jacobs' 'Cities First' Model and Archaeological Reality", International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38, 2014; doi:10.1111/1468-2427.12138.

- ↑ McQuillan (1937/1987), §1.03. "The ancients fostered the spread of urban culture; their efforts were constant to bring their people within the complete influence of municipal life. The desire to create cities was the most striking characteristic of the people of antiquity, and ancient rulers and statesmen vied with one another in satisfying that desire."

- ↑ Southall (1998), p. 23.

- ↑ Department of Ancient Near Eastern Art (October 2003). "Uruk: The First City". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ "Uruk (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ "What Science Has Learned about the Rise of Urban Mesopotamia". ThoughtCo. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ↑ Ring, Trudy (2014). Middle East and Africa: International Dictionary of Historic Places. p. 204.

- ↑ Jhimli Mukherjee Pandeyl, "Varanasi is as old as Indus valley civilization, finds IIT-KGP study", Times of India 25 February 2016.

- ↑ Kenoyer, Jonathan Mark (1998) Ancient Cities of the Indus Valley Civilization. Oxford University Press, Karachi and New York.

- ↑ Southall (1998), pp. 38–43.

- ↑ Moholy-Nagy (1968), pp. 158–161.

- ↑ Robert McCormick Adams Jr., Heartland of Cities: Surveys of Ancient Settlement and Land Use on the Central Floodplain of the Euphrates; University of Chicago Press, 1981; ISBN 0-226-00544-5; p. 2. "Southern Mesopotamia was a land of cities. It became one precociously, before the end of the fourth millennium B.C. Urban traditions remained strong and virtually continuous through the vicissitudes of conquest, internal upheaval accompanied by widespread economic breakdown, and massive linguistic and population replacement. The symbolic and material content of civilization obviously changed, but its cultural ambience remained tied to cities."

- ↑ Pocock, J.G.A. (1998). The Citizenship Debates. Chapter 2 – The Ideal of Citizenship since Classical Times (originally published in Queen's Quarterly 99, no. 1). Minneapolis, MN: The University of Minnesota. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-8166-2880-3.

- ↑ Ring, Salkin, Boda, Trudy, Robert, Sharon (1 January 1996). International Dictionary of Historic Places: Southern Europe. Routledge. p. 66. ISBN 978-1-884964-02-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 41–42. "Rome created an elaborate urban system. Roman colonies were organized as a means of securing Roman territory. The first thing that Romans did when they conquered new territories was to establish cities."

- ↑ Shady Solís, Ruth Martha (1997). La ciudad sagrada de Caral-Supe en los albores de la civilización en el Perú (in español). Lima: UNMSM, Fondo Editorial. Retrieved 3 March 2007.

- ↑ McIntosh, Roderic J., McIntosh, Susan Keech. "Early Urban Configurations on the Middle Niger: Clustered Cities and Landscapes of Power," Chapter 5.

- ↑ History of African Cities South of the Sahara Archived 2008-01-24 at the Wayback Machine By Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch. 2005. ISBN 1-55876-303-1

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), p. 43. "Capitals like Córdoba and Cairo had populations of about 500,000; Baghdad probably had a population of more than 1 million. This urban heritage would continue despite the conquests of the Seljuk Turks and the later Crusades. China, the longest standing civilization, was in the midst of a golden age as the Tang dynasty gave way—after a short period of fragmentation—to the Song dynasty. This dynasty ruled two of the most impressive cities on the planet, Xian and Hangzhou. / In contrast, poor Western Europe had not recovered from the sacking of Rome and the collapse of the western half of the Roman Empire. For more than five centuries a steady process of deurbanization—whereby the population living in cities and the number of cities declined precipitously—had converted a prosperous landscape into a scary wilderness, overrun with bandits, warlords, and rude settlements."

- ↑ Cameron, Averil (2009). The Byzantines. John Wiley and Sons. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-4051-9833-2. Retrieved 24 January 2015.

- ↑ Laiou, Angeliki E. (2002). "Writing the Economic History of Byzantium". In Angeliki E. Laiou (ed.). The Economic History of Byzantium (Volume 1). Washington, DC: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 130–131. Archived from the original on 18 February 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2012.

- ↑ "Free and Imperial Cities – Dictionary definition of Free and Imperial Cities". www.encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 47–50.

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Evans et al., A comprehensive archaeological map of the world's largest preindustrial settlement complex at Angkor, Cambodia, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the US, August 23, 2007.

- ↑ "Map reveals ancient urban sprawl", BBC News, 14 August 2007.

- ↑ Metropolis: Angkor, the world's first mega-city Archived 19 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine, The Independent, August 15, 2007

- ↑ Curtis (2016), pp. 5–6. "In the modern international system, cities were subjugated and internalized by the state, and, with industrialization, became the great growth engines of national economies."

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBlomley2013 - ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 53–54. "England was clearly at the center of these changes. London became the first truly global city by placing itself within the new global economy. English colonialism in North America, the Caribbean, South Asia, and later Africa and China helped to further fatten the wallets of many of its merchants. These colonies would later provide many of the raw materials for industrial production. England's hinterland was no longer confined to a portion of the world; it effectively became a global hinterland."

- ↑ Kaplan et al. (2004), pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Steven High, Industrial Sunset: The Making of North America's Rust Belt, 1969–1984; University of Toronto Press, 2003; ISBN 0-8020-8528-8. "It is now clear that the deindustrialization thesis is part myth and part fact. Robert Z. Lawrence, for example, uses aggregate economic data to show that manufacturing employment in the United States did not decline but actually increased from 16.8 million in 1960, to 20.1 million in 1973, and 20.3 million in 1980. However, manufacturing employment was in relative decline. Barry Bluestone noted that manufacturing represented a decreasing proportion of the U.S. labour force, from 26.2 per cent in 1973 to 22.1 per cent in 1980. Studies in Canada have likewise shown that manufacturing employment was only in relative decline during these years. Yet mills and factories did close, and towns and cities lost their industries. John Cumbler submitted that 'depressions do not manifest themselves only at moments of national economic collapse' such as in the 1930s, but 'also recur in scattered sites across the nation in regions, in industries, and in communities.'"

- ↑ Kaplan (2004), pp. 160–165. "Entrepreneurial leadership became manifest through growth coalitions made up of builders, realtors, developers, the media, government actors such as mayors, and dominant corporations. For example, in St. Louis, Anheuser-Busch, Monsanto, and Ralston Purina played prominent roles. The leadership involved cooperation between public and private interests. The results were efforts at downtown revitalization; inner-city gentrification; the transformation of the CBD to advanced service employment; entertainment, museums, and cultural venues; the construction of sports stadiums and sport complexes; and waterfront development."

- ↑ James Xiaohe Zhang, "Rapid urbanization in China and its impact on the world economy"; 16th Annual Conference on Global Economic Analysis, "New Challenges for Global Trade in a Rapidly Changing World", Shanhai Institute of Foreign Trade, June 12–14, 2013.

- ↑ Ian Johnson, "China's Great Uprooting: Moving 250 Million Into Cities"; New York Times, 15 June 2013.

- ↑ Castells, M. (ed) (2004). The network society: a cross-cultural perspective. London: Edward Elgar. (ebook)

- ↑ Flew, T. (2008). New media: an introduction, 3rd edn, South Melbourne: Oxford University Press

- ↑ Harford, T. (2008) The Logic of Life. London: Little, Brown.

- ↑ Taylor Shelton, Matthew Zook, & Alan Wiig, "The 'actually existing smart city'", Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy, and Society 8, 2015; doi:10.1093/cjres/rsu026.

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "lower-alpha", but no corresponding <references group="lower-alpha"/> tag was found