Gupta–Hunnic Wars: Difference between revisions

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

No edit summary Tags: Mobile edit Mobile web edit Advanced mobile edit |

||

| Line 164: | Line 164: | ||

The [[Hunas]] in [[Bactria]] were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both [[Iran]] and [[India]], and they might have tried to pursue [[Kidara I|Kidara]] or his successors in [[Gandhara]], and [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] refers to [[Hepthalite]] king trying to remove [[Buddha]]'s coliseum from [[Peshawar|Purushapur]]. This may indicate [[Huna people|Huna]] invasion in [[Gandhara]] some time before [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] concluded his peregrination in [[India]]. It is said that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the [[Hunas]], leaving his son Piro at [[Peshawar]]. It's possible that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] might have gained some help from the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor. It is thus possible that [[Chandragupta II]] led an adventure to [[Bactria]] through [[Gandhara]] against the [[Hunas]], and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of [[Sindhu]] and conquering [[Bahlikas|Bahlika]] in the [[Iron pillar of Delhi|Mehrauli Pillar Inscription]]. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. [[Chandragupta II]]'s [[Bactria]]n expedition also led to the battle of the [[Oxus]] with his [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor having planted the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] flag on the banks of the river of [[Oxus]].{{efn|"However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."{{sfn|Sinha|1974|p=[https://books.google.mu/books/about/Comprehensive_History_of_Bihar.html?id=2WlDAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y 50–51]}}}}{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=hRjC5IaJ2zcC&vq=Oxus&source=gbs_navlinks_s]240 & 264}} | The [[Hunas]] in [[Bactria]] were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both [[Iran]] and [[India]], and they might have tried to pursue [[Kidara I|Kidara]] or his successors in [[Gandhara]], and [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] refers to [[Hepthalite]] king trying to remove [[Buddha]]'s coliseum from [[Peshawar|Purushapur]]. This may indicate [[Huna people|Huna]] invasion in [[Gandhara]] some time before [[Faxian|Fa-hsien]] concluded his peregrination in [[India]]. It is said that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the [[Hunas]], leaving his son Piro at [[Peshawar]]. It's possible that [[Kidara I|Kidara]] might have gained some help from the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor. It is thus possible that [[Chandragupta II]] led an adventure to [[Bactria]] through [[Gandhara]] against the [[Hunas]], and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of [[Sindhu]] and conquering [[Bahlikas|Bahlika]] in the [[Iron pillar of Delhi|Mehrauli Pillar Inscription]]. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. [[Chandragupta II]]'s [[Bactria]]n expedition also led to the battle of the [[Oxus]] with his [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] emperor having planted the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta]] flag on the banks of the river of [[Oxus]].{{efn|"However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."{{sfn|Sinha|1974|p=[https://books.google.mu/books/about/Comprehensive_History_of_Bihar.html?id=2WlDAAAAYAAJ&redir_esc=y 50–51]}}}}{{sfn|Agrawal|1989|p=[https://books.google.mu/books?id=hRjC5IaJ2zcC&vq=Oxus&source=gbs_navlinks_s]240 & 264}} | ||

[[File:Inscription on Iron Pillar, Delhi.jpg|thumb|upright=1.27|The inscription of [[Chandragupta II]]]] | [[File:Inscription on Iron Pillar, Delhi.jpg|thumb|upright=1.27|The inscription of [[Chandragupta II]]]] | ||

== The Imperial crisis == | |||

=== Gupta interregnum === | |||

[[File:Silver Coin of Kumaragupta I.jpg|thumb|upright=1.5|Silver coin of the Gupta King [[Kumaragupta I]] (Coin of his Western territories, design derived from the [[Western Satraps]]). | |||

<br />''Obv'': Bust of king with crescents, with traces of corrupt Greek script.<ref>{{Cite book |url=https://books.google.com/books?id=_mUg2BBJr7kC&pg=PA112 |title=Coin splendour: a journey into the past |last=Prasanna Rao Bandela |publisher=Abhinav Publications |year=2003 |isbn=978-81-7017-427-1 |pages=112– |access-date=21 November 2011 |archive-date=29 May 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130529030958/http://books.google.com/books?id=_mUg2BBJr7kC&pg=PA112 |url-status=live}}</ref><ref>"Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of [[Chandragupta II]] is to be seen in his rare silver coins which are more directly imitated from those of the [[Western Satraps]]... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the reverse, they substitute the Gupta type (a peacock) for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc...", p. cli</ref> | |||

<br />''Rev'': [[Garuda]] standing facing with spread wings. Brahmi legend: ''Parama-bhagavata [[rajadhiraja]] Sri Kumaragupta Mahendraditya''.<ref>{{cite book |last1=Virji |first1=krishnakumari J. |title=Ancient History Of Saurashtra |date=1952 |page=225 |url=https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.57287/page/n249/mode/2up}}</ref>]] | |||

One of the topmost problems, which the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]], had to face in those times of excited conditioning, was the problem of race. At that time there were several ambitious tycoons in the Homeric family. [[Skandagupta]] and Purugupta were two of them. also, there was Ghatotkachagupta presumably also a son of [[Kumaragupta I]]. According to the law of royal race, which the ancient [[India]]n autocrats generally followed, the eldest son of [[Kumaragupta I]] should have succeeded him. But so far, the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] had shown spare respect to this principle. It's also not clear whether they regarded the first son sired on the senior-most queen or the eldest son, indeed if he happed to be the son of an inferior queen, as the licit descendant . maybe they hadn't bothered themselves to evolve a specific rule on this point. As regards the [[Hindu]] law books, it's nowhere laid down that the son of the principal-queen alone should succeed to the throne. In the early days of the conglomerate the nomination by the ruling autonomous was the most important factor. [[Chandragupta I]] had nominated [[Samudragupta]] as his successor and the ultimate, in his turn, presumably expressed his preference for his young son [[Chandragupta II]], over and above the claim of [[Ramagupta]], the elder brother of [[Chandragupta II]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=266-267}} | |||

It is not beyond the realm of possibility that towards the close of his reign, [[Kumaragupta I]] also expressed his preference for his valliant son [[Skandagupta]], though the evidence on this point is rather inconclusive. In this connection the Apratigha type of coins of the former furnish veritably intriguing substantiation. On the obverse of these issues we have three numbers. The central bone is really [[Kumaragupta I]] since he is expressly labelled as similar. He is shown wearing a dhoti. His hands are folded at midriff and he wears no jewelry on his person. He is adjoined on his right by a woman with her right hand bent up and raised in the station of ritarka (argumentation) and on his left by a joker, his left hand holding a guard and the right in the vitarka mudrā. According to Altekar, in this scene the emperor [[Kumaragupta I]] is shown as meaning repudiation and his queen and crown-prince are trying to inhibit him without success. The suggestion is relatively intriguing, though it is good to note that as these coins were issued during the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]] himself, he supposedly had not renounced his Homeric status altogether. To us it appears that in the ending times of his reign, [[Kumaragupta I]] entrusted the government of the conglomerate in the hands of his crown-prince and himself retired to lead a life of religious pursuits. Maybe commodity like this was behind the tradition recorded in the Kathasaritsagara according to which Mahendrāditya, generally linked with [[Kumaragupta I]], nominated his son Vikramaditya who had succeeded in inflicting a crushing defeat on the [[Mlecchas|Mlechchhas]] as his successor and himself retired to [[Varanasi]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=266-267}} | |||

According to the [[Buddhist]] work Chandragarbbapaṛiprichchhā also, the king Mahendrasena, identified with [[Kumaragupta I]] by K.P. Jayaswal, culminated his son Duprasahahasta, the whipper of the [[Yavanas]], Palhikas and Sakunas as his successor and himself retired to lead religious life. therefore, from the combined evidence of the Apratigha type of coins and the erudite tradition it appears that in his old age [[Kumaragupta I]] came virtually a isolate and the responsibility of administering his vast conglomerate regressed upon the shoulders of one of his sons. The prince who was named for this favour was supposedly no other than [[Skandagupta]], for, the Kathisarilsigara refers to him by the name of Vikramaditya, one of the titles espoused by [[Skandagupta]], and gives him the credit of conquering the [[Mlechchhas]], an achievement for which Skandagupta was regarded as the unique hero of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta dynasty]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=267-270}} | |||

[[File:KumaraguptaFightingLion.jpg|thumb|Kumaragupta I fighting a lion, as depicted on his gold coin<ref>CNG Coin [https://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=65341]</ref>]] | |||

Numerous scholars, still believe that [[Skandagupta]] had no licit right to the throne and [[Kumaragupta I]], indeed if he'd all his affections reserved for the former couldn't give his throne to him. But the arguments cited in support of this proposition aren't conclusive. The view that the expression talpādānadhyāta was reflective of legal right to the throne and accordingly its elision in the Bhitari necrology for [[Skandagupta]] suggests that his claim was not licit, is not correct. The expression didn't have any indigenous significance. It was used indeed by the feudatory autocrats to express their fidelity towards their overlord. It is also relatively possible that as the author of the Bhitari record switched over from prose to verse at the place where the expression tatpādānadhyāta was to be used for [[Skandagupta]] to describe his devotion to his father, he gave its lyrical interpretation pitṛiparigatapādapadmavarti. P.L. Gupta remarks that this expression does not convey the sense that [[Skandagupta]] was the favourite of [[Kumaragupta I]]; it rather reflects his own anxiety to show that he was veritably important devoted to his father. But does not the expression tatpādānudhyāta also suggest the same idea–the devotion of the sovereign for which it was used for his precursor? It should also not be forgotten that in the Bhitari record the expression tatpādanadhyāta has been used neither for Ghatotkacha and nor for [[Chandragupta I]] and [[Samudragupta]]. Would it mean that none of these autocrats was the licit successor of his father? As regards the status of the mother of [[Skandagupta]], the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of the Bhitari record does not inescapably prove that she was not a Mahādevi. As refocused out by Raychaudhuri, the names of the maters of the lords were occasionally neglected in the ordinary pratastis, however in the royal seals they were always appertained indeed if it meant reiteration.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

In the genealogical portion of the [[Madhuban]] and Banskhera plates, the name of Yaśomati as Harsha's mother is not mentioned, but in the [[Sonepat]] and [[Nalanda]] seals she is mentioned both as the mother of [[Rajyavardhana]] and as the mother of [[Harshavardhan|Harsha]]. The view that the mother of [[Skandagupta]] was a doxy of [[Kumaragupta I]] and not a full-fledged queen, and that [[Skandagupta]] was ashamed of her status is altogether unwarranted. [[Skandagupta]] refers to her veritably proudly in the verse 6 of the Bhitari record. The change-over from prose to verse incontinently after the name of [[Kumaragupta I]], which redounded in the lyrical picture of the expression tatpādānadhyāta was maybe also the cause of the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of this record.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

Actually, so far as the struggle for the throne among the sons of [[Kumaragupta I]] is concerned, the question of the legality of [[Skandagupta]] is hardly applicable. For, indeed if he was not entitled to inherit the conglomerate, he could raise the banner of rebellion against the licit descendant and could win the preceding struggle. still, as yet there is nothing to show that his claim was less justified than that of other contenders. He was putatively devoted to and had the blessings of his father–a fact which is also suggested by the installation by him of an image of Sārngin in the memory of [[Kumaragupta I]]. It also needs no arguments to prove that he must have been the darling of the Homeric army. His consecutive military palms suggest it veritably explosively. But his rivals were not exactly helpless. Take, for illustration, Purugupta. In the Bhitari seal of Kumaragupta II he's described as begotten on the Mahadevi Anantadevi. Now, from the Bihar gravestone pillar necrology we learn that [[Kumaragupta I]] had married the family of his minister Anantasena. As in that period sisters were generally named after their sisters, it is nearly insolvable not to imagine that the queen Anantadevi was the family of Anantasena, the Homeric minister.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=270-272}} | |||

However, it may be fluently conceded that Purugupta had an important section of ministers to support his candidature. If it was so. Then it may so be noted that after having consolidated his position as the new emperor, [[Skandagupta]] was obliged to appoint new 'pro-tectors' in all the businesses'. It may indicate that in some of the Homeric businesses his accession to the throne was opposed by the advanced officer-class. It is relatively possible that other contenders similar as Ghatotkachagupta, who had been the governor of the eastern [[Malwa]], reckoned substantially on similar original support. therefore, it appears that during the last times of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]] pulls from colorful directions sought to impact the question of race the emperor and the army favoured [[Skandagupta]], the queen Anantadevi and an important clerical party supported the cause of Purugupta and in some businesses original officers stoned the ambition of tycoons similar as Ghatotkachgupta. In such a condition, dominated by factional power- polities, a close contest for the throne was but ineluctable. Fortunately for the conglomerate, [[Skandagupta]], the unique hero of the [[Gupta Empire|Gupta dynasty]], who had the blessings of his father and the support of the Homeric army on his side surfaced victorious in it. His rise gave a farther parcel of life to the conglomerate the palm of a weaker seeker would have quickened the pace of decomposition.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|p=273}} | |||

=== Pushyamitra invasion === | |||

[[File:Narmada river map.jpg|thumb|The [[Pushyamitras]] lived on the banks of the [[Narmada River]].]] | |||

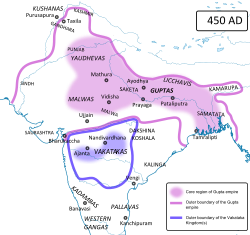

[[File:South Asia historical AD450 EN.svg|thumb|Political situation in [[India]] in 450 CE.]] | |||

Some of the troubles of [[Skandagupta]] were the result of the programs followed during the after times of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I]]. As we have seen, [[Kumaragupta I]] had launched a vigorous crusade against his [[Vakataka]] relations eventually towards the concluding period of his reign which coincided with the early times of the reign of [[Narendrasena]] (c. 440-60 A.D.), the son and successor of [[Pravarasena II]]. In this adventure, the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] had an important inferior supporter in the [[Nala]] king Bhavattavarman. But from the [[Vakataka]] records, it appears that Narendrasena veritably soon succeeded in reacquiring the fallen fortunes of his family.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

In this attempt, he was mainly helped by his [[Kadamba dynasty]] relations; else one can not explain why Prithvishena II, the son of Narendrasena, should have mentioned his maternal forefather in the line of his family. therefore, in the middle of the fifth century A.D. two power-blocks-one conforming of the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]] and the [[Nalas]] and the other comprising the [[Vakatakas]] and the [[Kadambas]] crystallized, and dominated the politics of the [[Deccan]]. Against this background the irruption of the [[Pushyamitras]], mentioned in the Bhitari record, assumes a new significance.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=273-274}} | |||

The identification and position of the home of the [[Pushyamitras]] of the Bhitari record have been largely controversial issues. But now it's generally honored that they belonged to the [[Mekala]] region. In the [[Vishnupurana]] MSS consulted by Wilson it's stated that the Pushpamitra (according to Wilson a variation of Pushyamitra), Patumitra and others, to the number of thirteen, will rule over [[Mekala]]. opining on this statement Wilson says" it seems most correct to separate the thirteen sons or families of the Vindhya queen( sic.) from these Bahlikas, and them from the Pushpamitras and Patumitras, who governed Mekala, a country on the Narmada.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

[[File:Mansar Shiva image.jpg|thumb|left|An image of [[Shiva]] from Mansar, currently housed in the [[National Museum, New Delhi]]. The image was likely produced during the reign of Pravarasena II, who was known to be a devout Shaivite.]] | |||

A statement of analogous import is set up in the [[Vaynpurana]] which is generally regarded as one of the oldest and the most dependable of Purana textbooks. It was on the base of this substantiation that Fleet and numerous others have located the [[Pushyamitras]] of the Bhitari record 'in [[central India]] nearly in the country along the banks of the [[Narmada]]'. Some scholars have expressed mistrustfulness about this suggestion, but the recent epigraphic discoveries haven't only given fresh support to his proposition but have also thrown a new light on the alignment of powers in this area. The most important of these documents is a bobby plate entitlement of the Pandavavarṁśi king [[Bharatabala]] alias Indra, discovered at [[Bamhani]] in [[Sohagpur]] tahsil of [[Rewa (princely state)|Rewa district]] in [[Baghelkhand]]. It records the entitlement of the village Vardhamanaka positioned in the Panchagarta Vishaya of Mekala to Lohita, a Brahmana of [[Vats (clan)|Vatsa gotra]]. Palaeographically, it has been credited to the middle of the fifth century A.D. by Chhabras and Mirashi. Accordingly, the origin of the [[Pandava]] family mentioned in it may be placed in the last quarter of the fourth century A.D.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

[[File:Nalanda clay seal of Vishnugupta.jpg|thumb|Nalanda clay seal of Vishnugupta]] | |||

It is true that in this record Jayabala and Vatstāja, the first two members of the family, have no royal title prefixed to their names, but it was maybe due to the fact that their description occurs in verse; the coming two lords are described both in prose and verse. In any case, it appears certain that the early autocrats of this family were the feudatories of the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]]. It is relatively possible that during the re-organisation of [[Baghelkhand]], [[Samudragupta]] gave an arena of Jayabala, the first member of this family. But the situation changed during the reign of Bharatabala. He is said to have married Lokaprakāśā, the queen of [[Kosala|Kosalā]]. She was presumably the son of the Sura king Bhimsena I who, according to Mirashi, was the contemporary of Bharatabala.{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

In the 11th verse of the [[Bahmani]] record, Bharatabala makes a veiled reference to a certain Narendra, who appears to have been his suzerain. Chhabra and Mirashi identify this Narendra with Narendrasena, the contemporary [[Vakataka]] sovereign . It is not at each insolvable, for, from the [[Balaghat]] plates of Prithvisheņa II(c. 460- 80A.D.), the son and successor of Narendrasena, we learn that the cominands of the ultimate were fete by the autocrats of [[Kosala]], Mekalā and Malavā. therefore, the combined evidence of the Bamhani and the Balaghat plates prove it nearly conclusively that eventually in the middle of the fifth centuryA.D. the sovereign of Mekala transferred his constancy from the Guptas to the Vakatakas. From what we know about the history of the contemporary period, it's insolvable not to suggest that it must have happed either towards the close of the reign of [[Kumaragupta I|Kumāragupta I]] or in the carly times of the reign of [[Skandagupta]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

It appears that as a response against the aggressive policy of the Guptas, which led to the occupation of the Vakataka capital Nandivardhana by Bhavattavarman, the Nala supporter of the Guptas, the Vakataka sovereign Narendrasena, soon after recovering the lost ground, launched an descent against the Guptas when their conglomerate was passing through a period of grave extremity. The [[Pandava]] sovereign Bharatabala of Mekalā readily transferred his constancy to him. Studied against this background, the statement of the Bhitari record that Skandagupta conquered "the Pushyamitras, who had developed great power and wealth, (and) he placed (his) left foot on a foot-stool which was the king (of that lineage himself)" becomes significant. It's impeccably in consonance with what we know of the history of the [[Mekala]] region to which the [[Pushyamitras]] belonged. supposedly, [[Pushyamitras]] king of the Bhitari record was no other than the Pandava sovereign of Mekala, the inferior supporter of Narendrasena Vakataka and his irruption on the Gupta conglomerate, obviously with the help of the Vakataka sovereign , was a part of the general descent which Narendrasena had launched against the [[Gupta Empire|Guptas]].{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=274-277}} | |||

=== The Second Huna invasion === | |||

During Skandagupta's period, the [[Indo-Hephthalites]] (known as the White Huns or [[Huna people|Hunas]]) invaded [[India]] from the northwest, advancing as far as the [[Indus River]].{{sfn|R. C. Majumdar|1981|p=73}} | |||

[[File:Kakandi Script.jpg|thumb|Madra inscription on the [[Kahaum pillar]]]] | |||

==== Battle of the Indus river (458 A.D.) ==== | |||

During the Hun invasion, a battle along the [[Indus river]] took place which resulted in [[Skandagupta]] checking the advances of the Huns with them facing heavy losses.{{sfn|Fisher|Yarshater|1968|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=Ko_RafMSGLkC]214}}{{sfn|Jaques|2007|p=[https://books.google.com/books?id=ss5drgEACAAJ] 471}}{{efn|"In their second attempt, which took place in the initial years of the reign of [[Skandagupta]], these barbarians shook the foundation of the empire, though somehow [[Skandagupta]] ultimately succeeded in checking the tide of their progress."{{sfn|Goyal|1967|pages=280–281}}}} | |||

{{multiple image|border=infobox|perrow=2/2/2|total_width=300 | |||

| align = right | |||

| direction =horizontal | |||

| header=Bhitari pillar of Skandagupta | |||

| image1 = Bhitari pillar of Skandagupta.jpg | |||

| image2 = Bhitari pillar.jpg | |||

| footer=The Bhitari pillar of [[Skandagupta]] | |||

}} | |||

The Bhitari pillar inscription states that [[Skandagupta]] defeated the [[Hunas]]:{{sfn|R. C. Majumdar|1981|p=73}} | |||

{{quote|([[Skandagupta]]), "by whose two arms the earth was shaken, when he, the creator (of a disturbance like that) of a terrible whirlpool, joined in close conflict with the [[Huna people|Hûnas]]; . . . . . . among enemies | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Revision as of 12:17, 1 July 2025

Gupta–Hunnic Wars was a series of the wars between the Hunas (Hunnics) and the Gupta Empire.

| Gupta–Hunnic Wars | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indo–Hunnic Wars | |||||||||

Approximate extent of the Alchon Huns, and find spots of inscriptions related to their local control (map of the Indian subcontinent)[1] | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Maukhari dynasty Aulikara dynasty |

Sakas | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Yashodharman Prakashadharman Ishanavarman Mātṛviṣṇu † Kidara I |

3 unknown Hepthalite kings (POW) & Khingila I Piro Bhūta Bharatbala Toramana Mihirakula (POW) Prakasaditya Harigupta Dhanyavishnu | ||||||||

Background

Samudragupta's Āryāvarta campaigns

According to the Allahabad Pillar inscription, Samudragupta "forcibly uprooted" the following kings of Aryavarta, the northern region:[10]

- Rudradeva

- Matila

- Nagadatta

- Chandravarman

- Ganapatinaga

- Nagasena

- Achyuta-nandin

- Balavarman

Unlike the southern kings, the inscription does not mention the territories ruled by these kings, which suggests that their kingdoms were annexed to the Gupta empire.[11] The inscription also mentions that Samudragupta defeated some other kings, but does not mention their names, presumably because the poet saw them as unimportant.[10]

Rise of Kidara Kushans

The emergence of the Great Kushans in Bactria and Northwestern India during the first century A.D. transformed these regions into significant players in international politics. The Kushan empire posed a dual threat to the Parthians of Iran. Economically, the Kushans, like the Parthians, acted as intermediaries in trade. They controlled three crucial sections of the renowned Silk Road: firstly, the route connecting the Caspian and Euxine Seas; secondly, the path passing through Merv, Hecatompylos, and Ecbatana, crossing the Euphrates and reaching Mediterranean ports; and thirdly, the maritime route between India and the Red Sea, which gained immense importance after the discovery of monsoons. Consequently, they had the ability to redirect trade between China, India, and the eastern countries away from Parthian territory, posing a significant economic challenge to Parthian rulers.[12]

The political implications of the Kushans' rise as a major power were also profound for Iran. Instead of facing a single enemy in the West, Iran found itself sandwiched between the Roman Empire and the Kushans. The Romans, who were constantly engaged in rivalry and conflict with the Parthians, recognized the strategic importance of this empire and sought direct relations with its rulers to safeguard trade routes between Rome, China, and India. Caught between these two powers, the early Sasanians, who succeeded the Parthians as the imperial rulers of Iran in 224 A.D., made the conquest of the Kushan empire their primary objective in Eastern policy, and they achieved remarkable success in this endeavor. The first Sasanian emperor, Ardashir I (224-241 A.D.), conquered Kushan principalities to the north of the Hindukush. Although Kushan chiefs continued to govern these territories, they had to accept the overlordship of the Sasanian emperor.[12]

Submission of Kidarites (Little Kushans)

The Kushan Empire continued as a remnant known as the "Little Kushans", based in the Punjab. Around 270 their territories on the Gangetic plain became independent under local dynasties such as the Yaudheyas. Then in the mid-4th century they were subjugated by the Gupta Empire under Samudragupta.[13] In his inscription on the Allahabad pillar Samudragupta proclaims that the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi (referring to the last Kushan rulers, being a deformation of the Kushan regnal titles Devaputra, Shao and Shaonanoshao: "Son of God, King, King of Kings") are now under his dominion, and that they were forced to "self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces".[14][13][15] This suggests that by the time of the Allahabad inscription the Kushans still ruled in Punjab, but under the suzerainty of the Gupta Emperor.[13]

North-western policy of Samudragupta

The reconstruction of Samudragupta's northwest policy mentioned earlier aligns with other intriguing facts. In 361 AD, an Indian delegation reportedly visited Rome, as stated by Roman historians. Despite having been dispatched from India earlier, the embassy did not reach Rome until 351 AD. Taking into account the political circumstances in India during the mid-4th century AD, this fact holds significant value. Before the year 361 AD, it was noted that the Roman emperors were engaged in a conflict with the Sassanids. Hence, it was not unexpected for Samudragupta to try to stop future conflicts with the Persian army on the Western Front by allying with Kidara I against Shahpur II. Hence, it is possible that he dispatched an embassy to Rome prior to 361 AD.[18]

Additionally, considering the political background of Bactria and north-west India described earlier, it is more probable that Kalidasa authored the Digvijaya story of Raghu using the real events resulting from Samudragupta's conquest, assuming great force. Kalidasa stated that Raghu conquered the Deccan's Trikutas before heading overland to conquer the Parasikas. Having emerged victorious over them, he went on to conquer the Hunas before launching an assault on the Kambojas. The Parasikas mentioned by Kalidasa are evidently related to the Sasanians. He mentioned that the Hunas resided by the Vankshu or Oxus river. During the third quarter of the fourth century AD, this was exactly the area where they resided. Ultimately, it may be concluded that the Kambojas of Raghuvamsa are likely to be the same as Kidara Kushans, as historical evidence shows that Kidara Inot only conquered Gandhara but also the five neighboring kingdoms, of course which were in Kambojas.[18]

Gupta-Kidara alliance

The Kushan contemporary of Samudragupta, was Kidāra. He was initially a part of the Great Kushan family. It was after him that his individuals got to be celebrated as the small Kushans. Hence, it can be promptly conceded that he was known to his counterparts as a ruler of the Devaputra family. But he was not effective enough to utilize the title Shahanushahi. He was simply a Shahi. His coins bearing the legend 'Kidāra Kushāṇa Shāhi' proved it. Subsequently, he can be effectively recognized with Daivaputrashāhi of the Allahabad pillar inscription. Here it is curiously to note that opposite to the for the most part acknowledged see, within the Prayaga Prasasti the word Devaputra has not been utilized as a title, for the reality that it has been utilized in its taddhita shape not simply appears that it must be taken in conjunction with the another word 'Shāhi', it moreover demonstrates that the compound Daivaputrashahi would connote 'Shāhi, who had a place to (the family of) the Devaputras'. As respects Kidāra's contemporary Shahanushahi, he might have been no other than Shapur II, the Sassanian Shahanshah. On the premise of this proposal the course of history of Bactria and North-Western India may be reproduced as takes after:

Kidara, after having set up himself in Gandhara, apparently at the cost of the Saka rulers, drew closer to Samudragupta a few times after 359 A. D., sent him presents and callings of steadfastness and inquired for his offer of assistance against the Sasanians. Samudragupta, on his part, was exceptionally much on edge to amplify his circle of impact past the central Punjab where his subordinate partners, the Gadaharas, were administering. He saw with uneasiness the tribal developments which were taking place in that heading and were posturing a risk to his recently established domain. But he was not a vanquisher, he was a statesman as well. He knew he possessed impediments and had the intelligence of restoring the prevailed rulers of the South.[21]

He needed to be included in a North-Western experience, indeed less. But, in any case, he was anxious to make the wildernesses of the domain and the western trade-routes secure and secure. He subsequently, did what was the most excellent; beneath the circumstances he concluded an alliance with Kidara and as the more grounded part of the association gave him an offer of assistance against Shapur II. His arrangement was prominently effective and Kidara vanquished the Sasanians twice in 367-68 A. D. It may not suggest that Shapur II got to be a vassal of Kidara or Samudragupta. But it does indicate that the articulation of Harishena about the connection of his master with the Sasanian ruler ought to not be suggested as through and through altogether without foundation.[21]

First Hephthalite invasion

Kidara, thereafter the year 367-68 A. D., likely in c. 370 A. D. had to bargain with the attack of the Jouan-Jouan or Hiung-nu or the White Huns from Bactria or Valhika. He put his son within the charge of his capital and went towards west to meet the intruders. This time too, Samudragupta shows up to have given considerable assistance to his Kushan ally. As a matter of truth, the victory of Kidara against the Hunas, whom he seem not check prior when he was in Bactria, demonstrates that this time he had an effective partner on his side. In this way, a fruitful endeavor by the Gupta sovereign in c. 370 A. D. against the Valhikas 'across the seven mouths of the river Indus' gets to be a really solid plausibility. It is one of the reasons which have driven us to hypothesize the identicality of the lord 'Chandra' with Samudragupta. It may, in any case, be recollected that the history of Bactria and the North-Western India as laid out over does not depend upon the recognizable proof of Samudragupta with the ruler of the Meharauli inscription. For example, in case we are to incline toward the hypothesis of the distinguishing proof of Chandragupta II with the ruler of this record, we can assume that it was Chandragupta, the offspring of Samudragupta, was the one sent as the pioneer of this expedition.[22]

Geographical factors in North-western policy

The general station of the ancient conglomerate-builders of the Ganga Valley towards the North-West was conditioned by the interplay of several factors. Geographically, the Indus valley is the western of cornucopia of what may be called the Fertile Crescent of India, and gives the print that it's nearly connected with the Ganga Valley. But there's another side of this picture also. It may be noted and needs to be emphasized that the Indus river-system is not only unconnected with any other river of North India, but it's indeed separated from the rest of the country by the vast desert of Thar. The stretch of the home which connects it with the Ganga Valley viz.[25]

The Thanesar-Delhi-Kurukshetra division–roughly the ancient realm of the Kuru Kingdom-is veritably narrow and communication through it was rendered delicate in the ancient times by the great timbers, similar as the Khandava, Kāmākhyā, Kurujāngala and Dvaitavana and also by a large number of small gutters. These walls, it seems, rendered the subjection of the Indus receptacle by the powers of the Ganga Valley relatively delicate and made these two regions to appear more distant and remote from each other than they actually were. It's a literal fact that with the exception of the Mauryas, nearly all the conglomerate-builders of the Ganga Valley the Nandas, the Sungas, the Nagas, the Guptas and indeed the Vardhanas noway seriously tried to conquer the region to the west of the Divide.[25]

It doesn't mean that they noway took any interest in the political fortunes of the Indus receptacle; they couldn't go to neglect it altogether. piecemeal from the fact that this region also belonged to the larger Indian world and, thus, the achievement of universal sovereignty (chakravartitra) was regarded as deficient without establishing some kind of suzerainty over it, they could hardly forget that utmost of the routes of the Indian trade with the Western countries were controlled by the North-Western powers. Above all, the nearly constant affluence via the Indus receptacle of Central and Western Asiatic peoples who relatively constantly hovered the security of the antarvedi itself, impelled them to take note of the political developments in the Indus receptacle. But these lodestones weren't sufficient enough to bait them to take over wars of subjection in that region.[25]

The Vardhanas, though a power of Thanesar, were interested in it only to the extent of transferring occasional peregrinations against the Hunas; the Sungas communicated some interest only when they were hovered by the Bactrian Greeks; indeed the Mauryan subjection of this region was maybe the result of the fact that Chandragupta Maurya started his political career there and the irruptions of Alexander and Seleucus had rendered its objectification in the conglomerate necessary. In the early mediaeval period also, the Rajput autocrats of the Ganga receptacle generally communicated interest in the politics of the Indus Valley states only when they were themselves hovered by the raiders coming from that direction. Prithviraja III, the Chahamanas of Shakambhari king of Delhi, for illustration, took no notice of the expansion of the Ghurid area in the Punjab till his own security was hovered and indeed after achieving palm in the first battle of Tarain he took no suitable way to oust the Muslims from the Punjab; he was putatively more interested in the politics of the antarvedi.[26]

In the light of the below discussion, the station of the Guptas towards the Indus Valley becomes comprehensible,

Chandragupta II's Expeditions

Battle of Begram

References to Kāpiši wine persist in literary works like Dhanapala's Tilakamanjari, describing it as a favored royal beverage with a reddish hue akin to a woman's eyes filled with resentment or the petals of a red lotus. Archaeological findings at Begram reveal ceramic motifs illustrating wine production, featuring jars, vines, grape bunches, and birds, reminiscent of Pompeii's artistry. Additionally, plaster medallions depict symmetrical arches formed by grape leaves and bunches, indicating Begram's historical significance as a grape-growing hub and wine production center.[27]

Recent archaeological endeavors uncovered a sizable wine cellar in Nisa, the former Parthian capital near modern-day Ashkabad, containing nearly 200,000 liters of wine stored in clay pitchers. Inscriptions on broken pieces of pitchers suggest wine distribution to significant establishments like Nisa's prominent slave-owning palace and temple. The mention of grape wine in the Raghuvamsa underscores the poet's geographical awareness of Kapisi's significance along land routes during Raghu's Persian campaign. After having crossed swords with the Yavanas. Raghu (Chandragupta II) fought a battle against the Parasikas (Persians) somewhere at the valley of Kāpiśi.[27]

Battle of Sistan and the Submission of Varahran

After the (Persian) Sasanians suffered defeat in the battle of Sistan, which demorilzed the Persian contingents in present day Afghanistan. As the Gupta Army marched northwards to Kapisa Province, Varahran was quick to grasp the political realities and offered his submission to the Gupta Emperor Chandragupta II.[28]

Gupta cavalry's arrival by the Oxus river

Bactria was under the Huna occupation in the last quarter of the fourth century AD.[lower-alpha 4] The sudden attack into the Oxus valley caught the Transoxiana alliance off-guard. The Pamir Mountains Tocharians were unable to combine with the Hunas (Hephtalites). On hearing the news of the Gupta Empire advanced, the Hephtalites resorted to a tactical retreat to the north of the Oxus River into the plains of southern Uzbekistan. When the Gupta cavalry arrived by the Oxus river on the southern banks, they camped there. Kalidasa poetically described how the cavalry camped on the banks of the river Vankshu in the midst of saffron fields in a verse of his Raghuvamsa:

"...His horses, that had lessened their fatigues of the road by turning from side to side on the banks of the river Vankshu (Oxus), shook their shoulders to which were clung the filaments of saffron..."

Historians studied this as a description of the Gupta cavalry camping on the banks of the Oxus during Chandragupta II's expedition.[31][32]

Kidara's conquest of Gandhara 356 CE and the Battle of the Oxus 399 CE

Kidara I (Late Brahmi script: ![]()

![]()

![]() Ki-da-ra; fl. 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.[34]

However, Altekar suggests that Candragupta II attacked the Kidara Kushans. But in the situation also prevailing it isn't insolvable that Chandragupta really raided Balkh or Bactria appertained to as Bahlikas in the inscription. We already saw that Bactria was enthralled by the Hepthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hunas on the Oxus) and therefore had led to the eventual subjection of Gandhara by Kidara by 356 A.D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudragupta). After Kidara, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudragupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidara, and he also claims to have entered the submission of Shāhānushāhī (the Sasanian emperor), substantially to consolidate his vanquishing in the country, and to have some share and control over the renowned Silk-route.[lower-alpha 5]

Ki-da-ra; fl. 350-390 CE) was the first major ruler of the Kidarite Kingdom, which replaced the Indo-Sasanians in northwestern India, in the areas of Kushanshahr, Gandhara, Kashmir and Punjab.[34]

However, Altekar suggests that Candragupta II attacked the Kidara Kushans. But in the situation also prevailing it isn't insolvable that Chandragupta really raided Balkh or Bactria appertained to as Bahlikas in the inscription. We already saw that Bactria was enthralled by the Hepthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hunas on the Oxus) and therefore had led to the eventual subjection of Gandhara by Kidara by 356 A.D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudragupta). After Kidara, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudragupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidara, and he also claims to have entered the submission of Shāhānushāhī (the Sasanian emperor), substantially to consolidate his vanquishing in the country, and to have some share and control over the renowned Silk-route.[lower-alpha 5]

The Hunas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because they posed peril to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidara or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Hepthalite king trying to remove Buddha's coliseum from Purushapur. This may indicate Huna invasion in Gandhara some time before Fa-hsien concluded his peregrination in India. It is said that Kidara towards the end of the 4th century had to go northwestwards against the Hunas, leaving his son Piro at Peshawar. It's possible that Kidara might have gained some help from the Gupta emperor. It is thus possible that Chandragupta II led an adventure to Bactria through Gandhara against the Hunas, and this may be appertained to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bahlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A.D. Chandragupta II's Bactrian expedition also led to the battle of the Oxus with his Gupta cavalry against the Hunas, who were defeated and the Gupta emperor having planted the Gupta flag on the banks of the river of Oxus.[lower-alpha 6][38]

The Imperial crisis

Gupta interregnum

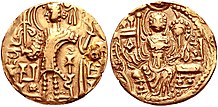

Obv: Bust of king with crescents, with traces of corrupt Greek script.[39][40]

Rev: Garuda standing facing with spread wings. Brahmi legend: Parama-bhagavata rajadhiraja Sri Kumaragupta Mahendraditya.[41]

One of the topmost problems, which the Guptas, had to face in those times of excited conditioning, was the problem of race. At that time there were several ambitious tycoons in the Homeric family. Skandagupta and Purugupta were two of them. also, there was Ghatotkachagupta presumably also a son of Kumaragupta I. According to the law of royal race, which the ancient Indian autocrats generally followed, the eldest son of Kumaragupta I should have succeeded him. But so far, the Guptas had shown spare respect to this principle. It's also not clear whether they regarded the first son sired on the senior-most queen or the eldest son, indeed if he happed to be the son of an inferior queen, as the licit descendant . maybe they hadn't bothered themselves to evolve a specific rule on this point. As regards the Hindu law books, it's nowhere laid down that the son of the principal-queen alone should succeed to the throne. In the early days of the conglomerate the nomination by the ruling autonomous was the most important factor. Chandragupta I had nominated Samudragupta as his successor and the ultimate, in his turn, presumably expressed his preference for his young son Chandragupta II, over and above the claim of Ramagupta, the elder brother of Chandragupta II.[42]

It is not beyond the realm of possibility that towards the close of his reign, Kumaragupta I also expressed his preference for his valliant son Skandagupta, though the evidence on this point is rather inconclusive. In this connection the Apratigha type of coins of the former furnish veritably intriguing substantiation. On the obverse of these issues we have three numbers. The central bone is really Kumaragupta I since he is expressly labelled as similar. He is shown wearing a dhoti. His hands are folded at midriff and he wears no jewelry on his person. He is adjoined on his right by a woman with her right hand bent up and raised in the station of ritarka (argumentation) and on his left by a joker, his left hand holding a guard and the right in the vitarka mudrā. According to Altekar, in this scene the emperor Kumaragupta I is shown as meaning repudiation and his queen and crown-prince are trying to inhibit him without success. The suggestion is relatively intriguing, though it is good to note that as these coins were issued during the reign of Kumaragupta I himself, he supposedly had not renounced his Homeric status altogether. To us it appears that in the ending times of his reign, Kumaragupta I entrusted the government of the conglomerate in the hands of his crown-prince and himself retired to lead a life of religious pursuits. Maybe commodity like this was behind the tradition recorded in the Kathasaritsagara according to which Mahendrāditya, generally linked with Kumaragupta I, nominated his son Vikramaditya who had succeeded in inflicting a crushing defeat on the Mlechchhas as his successor and himself retired to Varanasi.[42]

According to the Buddhist work Chandragarbbapaṛiprichchhā also, the king Mahendrasena, identified with Kumaragupta I by K.P. Jayaswal, culminated his son Duprasahahasta, the whipper of the Yavanas, Palhikas and Sakunas as his successor and himself retired to lead religious life. therefore, from the combined evidence of the Apratigha type of coins and the erudite tradition it appears that in his old age Kumaragupta I came virtually a isolate and the responsibility of administering his vast conglomerate regressed upon the shoulders of one of his sons. The prince who was named for this favour was supposedly no other than Skandagupta, for, the Kathisarilsigara refers to him by the name of Vikramaditya, one of the titles espoused by Skandagupta, and gives him the credit of conquering the Mlechchhas, an achievement for which Skandagupta was regarded as the unique hero of the Gupta dynasty.[43]

Numerous scholars, still believe that Skandagupta had no licit right to the throne and Kumaragupta I, indeed if he'd all his affections reserved for the former couldn't give his throne to him. But the arguments cited in support of this proposition aren't conclusive. The view that the expression talpādānadhyāta was reflective of legal right to the throne and accordingly its elision in the Bhitari necrology for Skandagupta suggests that his claim was not licit, is not correct. The expression didn't have any indigenous significance. It was used indeed by the feudatory autocrats to express their fidelity towards their overlord. It is also relatively possible that as the author of the Bhitari record switched over from prose to verse at the place where the expression tatpādānadhyāta was to be used for Skandagupta to describe his devotion to his father, he gave its lyrical interpretation pitṛiparigatapādapadmavarti. P.L. Gupta remarks that this expression does not convey the sense that Skandagupta was the favourite of Kumaragupta I; it rather reflects his own anxiety to show that he was veritably important devoted to his father. But does not the expression tatpādānudhyāta also suggest the same idea–the devotion of the sovereign for which it was used for his precursor? It should also not be forgotten that in the Bhitari record the expression tatpādanadhyāta has been used neither for Ghatotkacha and nor for Chandragupta I and Samudragupta. Would it mean that none of these autocrats was the licit successor of his father? As regards the status of the mother of Skandagupta, the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of the Bhitari record does not inescapably prove that she was not a Mahādevi. As refocused out by Raychaudhuri, the names of the maters of the lords were occasionally neglected in the ordinary pratastis, however in the royal seals they were always appertained indeed if it meant reiteration.[45]

In the genealogical portion of the Madhuban and Banskhera plates, the name of Yaśomati as Harsha's mother is not mentioned, but in the Sonepat and Nalanda seals she is mentioned both as the mother of Rajyavardhana and as the mother of Harsha. The view that the mother of Skandagupta was a doxy of Kumaragupta I and not a full-fledged queen, and that Skandagupta was ashamed of her status is altogether unwarranted. Skandagupta refers to her veritably proudly in the verse 6 of the Bhitari record. The change-over from prose to verse incontinently after the name of Kumaragupta I, which redounded in the lyrical picture of the expression tatpādānadhyāta was maybe also the cause of the elision of her name in the genealogical portion of this record.[45]

Actually, so far as the struggle for the throne among the sons of Kumaragupta I is concerned, the question of the legality of Skandagupta is hardly applicable. For, indeed if he was not entitled to inherit the conglomerate, he could raise the banner of rebellion against the licit descendant and could win the preceding struggle. still, as yet there is nothing to show that his claim was less justified than that of other contenders. He was putatively devoted to and had the blessings of his father–a fact which is also suggested by the installation by him of an image of Sārngin in the memory of Kumaragupta I. It also needs no arguments to prove that he must have been the darling of the Homeric army. His consecutive military palms suggest it veritably explosively. But his rivals were not exactly helpless. Take, for illustration, Purugupta. In the Bhitari seal of Kumaragupta II he's described as begotten on the Mahadevi Anantadevi. Now, from the Bihar gravestone pillar necrology we learn that Kumaragupta I had married the family of his minister Anantasena. As in that period sisters were generally named after their sisters, it is nearly insolvable not to imagine that the queen Anantadevi was the family of Anantasena, the Homeric minister.[45]

However, it may be fluently conceded that Purugupta had an important section of ministers to support his candidature. If it was so. Then it may so be noted that after having consolidated his position as the new emperor, Skandagupta was obliged to appoint new 'pro-tectors' in all the businesses'. It may indicate that in some of the Homeric businesses his accession to the throne was opposed by the advanced officer-class. It is relatively possible that other contenders similar as Ghatotkachagupta, who had been the governor of the eastern Malwa, reckoned substantially on similar original support. therefore, it appears that during the last times of the reign of Kumaragupta I pulls from colorful directions sought to impact the question of race the emperor and the army favoured Skandagupta, the queen Anantadevi and an important clerical party supported the cause of Purugupta and in some businesses original officers stoned the ambition of tycoons similar as Ghatotkachgupta. In such a condition, dominated by factional power- polities, a close contest for the throne was but ineluctable. Fortunately for the conglomerate, Skandagupta, the unique hero of the Gupta dynasty, who had the blessings of his father and the support of the Homeric army on his side surfaced victorious in it. His rise gave a farther parcel of life to the conglomerate the palm of a weaker seeker would have quickened the pace of decomposition.[46]

Pushyamitra invasion

Some of the troubles of Skandagupta were the result of the programs followed during the after times of the reign of Kumaragupta I. As we have seen, Kumaragupta I had launched a vigorous crusade against his Vakataka relations eventually towards the concluding period of his reign which coincided with the early times of the reign of Narendrasena (c. 440-60 A.D.), the son and successor of Pravarasena II. In this adventure, the Guptas had an important inferior supporter in the Nala king Bhavattavarman. But from the Vakataka records, it appears that Narendrasena veritably soon succeeded in reacquiring the fallen fortunes of his family.[47]

In this attempt, he was mainly helped by his Kadamba dynasty relations; else one can not explain why Prithvishena II, the son of Narendrasena, should have mentioned his maternal forefather in the line of his family. therefore, in the middle of the fifth century A.D. two power-blocks-one conforming of the Guptas and the Nalas and the other comprising the Vakatakas and the Kadambas crystallized, and dominated the politics of the Deccan. Against this background the irruption of the Pushyamitras, mentioned in the Bhitari record, assumes a new significance.[48]

The identification and position of the home of the Pushyamitras of the Bhitari record have been largely controversial issues. But now it's generally honored that they belonged to the Mekala region. In the Vishnupurana MSS consulted by Wilson it's stated that the Pushpamitra (according to Wilson a variation of Pushyamitra), Patumitra and others, to the number of thirteen, will rule over Mekala. opining on this statement Wilson says" it seems most correct to separate the thirteen sons or families of the Vindhya queen( sic.) from these Bahlikas, and them from the Pushpamitras and Patumitras, who governed Mekala, a country on the Narmada.[47]

A statement of analogous import is set up in the Vaynpurana which is generally regarded as one of the oldest and the most dependable of Purana textbooks. It was on the base of this substantiation that Fleet and numerous others have located the Pushyamitras of the Bhitari record 'in central India nearly in the country along the banks of the Narmada'. Some scholars have expressed mistrustfulness about this suggestion, but the recent epigraphic discoveries haven't only given fresh support to his proposition but have also thrown a new light on the alignment of powers in this area. The most important of these documents is a bobby plate entitlement of the Pandavavarṁśi king Bharatabala alias Indra, discovered at Bamhani in Sohagpur tahsil of Rewa district in Baghelkhand. It records the entitlement of the village Vardhamanaka positioned in the Panchagarta Vishaya of Mekala to Lohita, a Brahmana of Vatsa gotra. Palaeographically, it has been credited to the middle of the fifth century A.D. by Chhabras and Mirashi. Accordingly, the origin of the Pandava family mentioned in it may be placed in the last quarter of the fourth century A.D.[47]

It is true that in this record Jayabala and Vatstāja, the first two members of the family, have no royal title prefixed to their names, but it was maybe due to the fact that their description occurs in verse; the coming two lords are described both in prose and verse. In any case, it appears certain that the early autocrats of this family were the feudatories of the Guptas. It is relatively possible that during the re-organisation of Baghelkhand, Samudragupta gave an arena of Jayabala, the first member of this family. But the situation changed during the reign of Bharatabala. He is said to have married Lokaprakāśā, the queen of Kosalā. She was presumably the son of the Sura king Bhimsena I who, according to Mirashi, was the contemporary of Bharatabala.[47]

In the 11th verse of the Bahmani record, Bharatabala makes a veiled reference to a certain Narendra, who appears to have been his suzerain. Chhabra and Mirashi identify this Narendra with Narendrasena, the contemporary Vakataka sovereign . It is not at each insolvable, for, from the Balaghat plates of Prithvisheņa II(c. 460- 80A.D.), the son and successor of Narendrasena, we learn that the cominands of the ultimate were fete by the autocrats of Kosala, Mekalā and Malavā. therefore, the combined evidence of the Bamhani and the Balaghat plates prove it nearly conclusively that eventually in the middle of the fifth centuryA.D. the sovereign of Mekala transferred his constancy from the Guptas to the Vakatakas. From what we know about the history of the contemporary period, it's insolvable not to suggest that it must have happed either towards the close of the reign of Kumāragupta I or in the carly times of the reign of Skandagupta.[47]

It appears that as a response against the aggressive policy of the Guptas, which led to the occupation of the Vakataka capital Nandivardhana by Bhavattavarman, the Nala supporter of the Guptas, the Vakataka sovereign Narendrasena, soon after recovering the lost ground, launched an descent against the Guptas when their conglomerate was passing through a period of grave extremity. The Pandava sovereign Bharatabala of Mekalā readily transferred his constancy to him. Studied against this background, the statement of the Bhitari record that Skandagupta conquered "the Pushyamitras, who had developed great power and wealth, (and) he placed (his) left foot on a foot-stool which was the king (of that lineage himself)" becomes significant. It's impeccably in consonance with what we know of the history of the Mekala region to which the Pushyamitras belonged. supposedly, Pushyamitras king of the Bhitari record was no other than the Pandava sovereign of Mekala, the inferior supporter of Narendrasena Vakataka and his irruption on the Gupta conglomerate, obviously with the help of the Vakataka sovereign , was a part of the general descent which Narendrasena had launched against the Guptas.[47]

The Second Huna invasion

During Skandagupta's period, the Indo-Hephthalites (known as the White Huns or Hunas) invaded India from the northwest, advancing as far as the Indus River.[49]

Battle of the Indus river (458 A.D.)

During the Hun invasion, a battle along the Indus river took place which resulted in Skandagupta checking the advances of the Huns with them facing heavy losses.[50][51][lower-alpha 7]

The Bhitari pillar inscription states that Skandagupta defeated the Hunas:[49]

{{quote|(Skandagupta), "by whose two arms the earth was shaken, when he, the creator (of a disturbance like that) of a terrible whirlpool, joined in close conflict with the Hûnas; . . . . . . among enemies

Notes

- ↑ " The Mehrauli Pillar Inscription (No.20) describes the digvijaya of a king named Candra (i.e. Candragupta II) in the first verse as stated below :

"He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries, he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against him;—he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vāhlikas;—he by the breezes of whose prowess the Southern ocean is even still perfumed".

We find various readings of the name Vāhlika in literature which are : Vāhlika, Bāhlika, Vāhlīka and Bāhlīka. In our inscription (No. 20) 'Vāhilikāḥ', i.e. Bactria (modern Balkh) region on the Oxus in the northern part of Afghanistan."[6]

- ↑ J. F. Fleet's 1888 translation is as follows:[7]

(Verse 1) He, on whose arm fame was inscribed by the sword, when, in battle in the Vanga countries (Bengal), he kneaded (and turned) back with (his) breast the enemies who, uniting together, came against (him); – he, by whom, having crossed in warfare the seven mouths of the (river) Sindhu, the Vahlikas were conquered; – he, by the breezes of whose prowess the southern ocean is even still perfumed; –

- ↑ "THE SECOND HUNA INVASION

The attitude of the imperial Guptas towards the North-West presents a very interesting problem for the students of their history. It is quite apparent that they had the power and resources to incorporate the Indus basin in their empire ; but they did nothing more than imposing a vague sort of suzerainty over it which did not last very long."[8] - ↑ "Taking Kālidāsa to be a contemporary of Chandragupta II, we can conclude that the Hūṇas had occupied Bactria in the last quarter of the fourth century AD." [30]

- ↑ "However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."[35]

- ↑ "However, Altekar suggests that Candra Gupta attacked the Kidara Kushāṇas. But in the situation then prevailing it is not impossible that Candra Gupta really invaded Balkh or Bactria referred to as Bāhlika in the inscription. We have seen that Bactria was occupied by the Epthalites in about 350 A.D. (Kalidasa refers to the Hūņas on the Oxus) and thus had led to the eventual conquest of Gandhara by Kidāra by 356 A. D., the contemporary (Daivaputrashātā of Samudra Gupta). After Kidāra, his successors were known as little Yue-chi. As we have seen Samudra Gupta was satisfied with the offer of submission of Kidāra, and he also claims to have received the submission of Shāhānushāhī, (the Sassanian emperor), mainly to consolidate his conquests in the country, and to have some share and control over the famous Silk-route. The Hūṇas in Bactria were not a peaceful community and because a danger to both Iran and India, and they might have tried to pursue Kidāra or his successors in Gandhara, and Fa-hsien refers to Epthalite king trying to remove Buddha's bowl from Purushapur. This may indicate Hūṇa inroad in Gandhāra some time before Fa-hsien concluded his travels in India. It is held that Kidāra towards the end of the 4th century had to proceed N. W. against the Hūṇas leaving his son Piro at Peshwar. It is possible that Kidāra might have received some help from the Gupta emperor. It is therefore possible that Candra Gupta II led an expedition to Bactria through Gandhāra against the Hūṇas, and this may be referred to as his crossing of the seven rivers of Sindhu and conquering Bāhlika in the Mehrauli Pillar Inscription. This event may be placed towards the end of the 4th century A. D."[35]

- ↑ "In their second attempt, which took place in the initial years of the reign of Skandagupta, these barbarians shook the foundation of the empire, though somehow Skandagupta ultimately succeeded in checking the tide of their progress."[52]

Reference

- ↑ Hans Bakker 24th Gonda lecture

- ↑ Bakker 2020, pp. 31–34.

- ↑ Bakker 2020, p. 34.

- ↑ Majumdar, R. C., ed. (1970). History and Culture of the Indian People, Volume 03, The Classical Age. Public Resource. Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan. p. 38.

- ↑ History Of The Imperial Guptas. p. 350.

- ↑ Tej Ram Sharma 1978, p. 167.

- ↑ Balasubramaniam 2005, pp. 7–8.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, p. 277.

- ↑ "The young son of Mahendrasena led his father's army of two hundred thousand men against the enemy whose soldiers numbered three hundred thousand. The prince however, broke the enemy army and won the battle. On his return his father crown him saying "henceforth rule the kingdom," and himself retired to religious life. For twelve years after this, the new king fought these foreign enemies, and ultimately captured and executed the three kings.' It has been suggested that this story gives an account of the fight between Skandagupta and the Hūṇas (IHIJ. 36)." The History and Culture of the Indian People: The classical age. G. Allen & Unwin. 1951. p. 27.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Agrawal 1989, p. 114.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 22.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Goyal 1967, p. 169.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Dani, Litvinsky & Zamir Safi 1996, pp. 165–166

- ↑ Lines 23-24 of the Allahabad pillar inscription of Samudragupta: "Self-surrender, offering (their own) daughters in marriage and a request for the administration of their own districts and provinces through the Garuḍa badge, by the Dēvaputra-Shāhi-Shāhānushāhi and the Śaka lords and by (rulers) occupying all Island countries, such as Siṁhala and others."

- ↑ Cribb, Joe; Singh, Karan (Winter 2017). "Two Curious Kidarite Coin Types From 3rd Century Kashmir". JONS. 230: 3.

- ↑ A similar coin with reading of the legend

- ↑ Lerner, Judith A. (210). Observations on the Typology and Style of Seals and Sealings from Bactria and the Indo-Iranian Borderlands, in Coins, Art and Chronology II. The First Millennium CE in the Indo-Iranian Borderlands. Vienna: ÖAW. p. 246, note 7.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Goyal 1967, pp. 179-180.

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Attila, Michael Maas, Cambridge University Press, 2014 p.284sq

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Iranica, article Kidarites: "On Gandhāran coins bearing their name the ruler is always clean-shaven, a fashion more typical of Altaic people than of Iranians" in "KIDARITES – Encyclopaedia Iranica". www.iranicaonline.org.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Goyal 1967, pp. 177-178.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 178-179.

- ↑ KURBANOV, AYDOGDY (2010). THE HEPHTHALITES: ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND HISTORICAL ANALYSIS (PDF). Berlin: Department of History and Cultural Studies of the Free University. p. 39.

- ↑ Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. Oxford University Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-19-933079-9.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Goyal 1967, pp. 280-281.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 278-280.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Prakash 1962, p. [1]337-338.

- ↑ Prakash 1962, p. [2]Chapter XIII and Chapter XIV.

- ↑ *Template:British-Museum-db

- ↑ "The Raghuvamsa Of Kalidasa. With The Commentary Of Mallinatha by Nandargikar, Gopal Raghunath: used/Good rebound full cloth (1982) | Prabhu Book Exports". www.abebooks.co.uk. p. verse 66, Chapter XIII. Retrieved 22 March 2024.

- ↑ Agrawal 1989, p. [4]166.

- ↑ Tandon, Pankaj (2009). "An Important New Copper Coin of Gadahara". Journal of the Oriental Numismatic Society (200): 19.

- ↑ History of Civilizations of Central Asia, Ahmad Hasan Dani, B. A. Litvinsky, Unesco p.38 sq

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Sinha 1974, p. 50–51.

- ↑ Bandela, Prasanna Rao (2003). Coin Splendour: A Journey into the Past. Abhinav Publications. p. 11. ISBN 9788170174271.

- ↑ Allen 1914, p. 24.

- ↑ Prasanna Rao Bandela (2003). Coin splendour: a journey into the past. Abhinav Publications. pp. 112–. ISBN 978-81-7017-427-1. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ "Evidence of the conquest of Saurastra during the reign of Chandragupta II is to be seen in his rare silver coins which are more directly imitated from those of the Western Satraps... they retain some traces of the old inscriptions in Greek characters, while on the reverse, they substitute the Gupta type (a peacock) for the chaitya with crescent and star." in Rapson "A catalogue of Indian coins in the British Museum. The Andhras etc...", p. cli

- ↑ Virji, krishnakumari J. (1952). Ancient History Of Saurashtra. p. 225.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Goyal 1967, pp. 266-267.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 267-270.

- ↑ CNG Coin [6]

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Goyal 1967, pp. 270-272.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, p. 273.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 47.4 47.5 Goyal 1967, pp. 274-277.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 273-274.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 R. C. Majumdar 1981, p. 73.

- ↑ Fisher & Yarshater 1968, p. [7]214.

- ↑ Jaques 2007, p. [8] 471.

- ↑ Goyal 1967, pp. 280–281.