Seleucid–Mauryan war

Thank you for being part of the Bharatpedia family! 0% transparency: ₹0 raised out of ₹100,000 (0 supporter) |

| Seleucid–Mauryan War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Conquests of Maurya Empire | |||||||

Alexander the Great's Satrapies in Northern India. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Maurya Empire | Seleucid Empire | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Chandragupta Maurya Chanakya | Seleucus I Nicator | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| unknown | unknown | ||||||

The Seleucid–Mauryan War was fought between 305 and 303 BC. It started when Seleucus I Nicator, of the Seleucid Empire, sought to retake the Indian satrapies of the Macedonian Empire which had been occupied by Emperor Chandragupta Maurya, of the Maurya Empire.

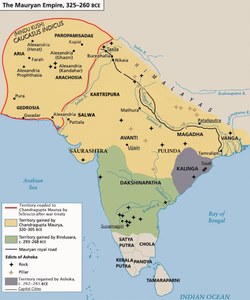

The war ended in a settlement resulting in the annexation of the Indus Valley region and part of Afghanistan to the Mauryan Empire, with Chandragupta securing control over the areas that he had sought, and a marriage alliance between the two powers. After the war, the Mauryan Empire emerged as the dominant power of the Indian subcontinent, and the Seleucid Empire turned its attention toward defeating its rivals in the west.

Background

Chandragupta Maurya established himself as ruler of Magadha around 321 BC. He decided to conquer the Nanda Dynasty, rulers at the time of the Gangetic Plain. He fought the empire for eleven years with successful guerrilla campaigns, and captured the Nanda capital of Pataliputra. This led to the fall of the empire and the eventual creation of the Maurya Empire under Emperor Chandragupta Maurya.

The Persian provinces in what is now modern Afghanistan, together with the wealthy kingdom of Gandhara and the states of the Indus Valley, had all submitted to Alexander the Great and become part of his empire. When Alexander died, the Wars of the Diadochi ("Successors") split his empire apart; as his generals fought for control of Alexander's empire. In the eastern territories one of these generals, Seleucus I Nicator, was taking control and was starting to establish what became known as the Seleucid Empire.

Seleucus reconquest of Alexander empire

According to the Roman historian Appian, Seleucus,

Always lying in wait for the neighboring nations, strong in arms and persuasive in council, he acquired Mesopotamia, Armenia, 'Seleucid' Cappadocia, Persis, Parthia, Bactria, Arabia, Tapouria, Sogdia, Arachosia, Hyrcania, and other adjacent peoples that had been subdued by Alexander, as far as the river Indus, so that the boundaries of his empire were the most extensive in Asia after that of Alexander. The whole region from Phrygia to the Indus was subject to Seleucus.

Alexander had appointed satraps in control of his territories. Similarly satraps were appointed to govern the Indus Valley. The Mauryans had annexed the areas governed by four such satraps: Nicanor, Phillip, Eudemus and Peithon. This established Mauryan control to the banks of the Indus. Chandragupta's victories convinced Seleucus that he needed to secure his eastern flank. Seeking to hold the Macedonian territories there, Seleucus thus came into conflict with the emerging and expanding Mauryan Empire over the Indus Valley.[4]

Seleucid–Chandragupta war and result

Conflict and Epigamia

According to Greek historian Appian,

He (Seleucus) crossed the Indus and waged war with Sandrocottus [Maurya], king of the Indians, who dwelt on the banks of that stream, until they came to an understanding with each other and contracted a marriage relationship.

Chandragupta and Seleucus concluded a peace treaty and a marriage alliance in 303 BCE. Chandragupta received vast territories and in a return gave Seleucus 500 war elephants,[11][12][13][14][15] a military asset which would play a decisive role at the Battle of Ipsus in 301 BCE.[16] In addition to this treaty, Seleucus dispatched an ambassador, Megasthenes, to Chandragupta, and later Deimakos to his son Bindusara, at the Mauryan court at Pataliputra (modern Patna in Bihar). Later, Ptolemy II Philadelphus, the ruler of Ptolemaic Egypt and contemporary of Ashoka, is also recorded by Pliny the Elder as having sent an ambassador named Dionysius to the Mauryan court.[17]

Treaty of Indus

According to Latin historian Justin,

After having made a treaty with him (Sandrakotos) and put in order the Orient situation, Seleucos went to war against Antigonus.

— Junianus Justinus, Historiarum Philippicarum, libri XLIV, XV.4.15

The treaty on "Epigamia" implies lawful marriage between Greeks and Indians.[citation needed]

The ancient Greecian Historians Justin, Appian, and Strabo preserve the three main terms of the Treaty of the Indus:[18]

- (i) Seleucus transferred to Chandragupta's kingdom the easternmost satrapies of his empire, certainly Gandhara, Paropamisadae, and the eastern parts of Gedrosia, Arachosia and Aria as far as Herat.

- (ii) Chandragupta Maurya gave Seleucus 500 Indian war elephants.

- (iii) Epigamia: The two kings were joined by some kind of marriage alliance (ἐπιγαμία οι κῆδος); most likely Chandragupta wed a female relative of Seleucus.

Exchange of presents

Classical sources have also recorded that following their treaty, Chandragupta and Seleucus exchanged presents, such as when Chandragupta sent various aphrodisiacs to Seleucus:[19]

And Theophrastus says that some contrivances are of wondrous efficacy in such matters [as to make people more amorous]. And Phylarchus confirms him, by reference to some of the presents which Sandrakottus, the king of the Indians, sent to Seleucus; which were to act like charms in producing a wonderful degree of affection, while some, on the contrary, were to banish love.

Sandrakottus son Bindusara 'Amitraghata' (Slayer of Enemies) also is recorded in Classical sources as having exchanged presents with Antiochus I:[19]

But dried figs were so very much sought after by all men (for really, as Aristophanes says, "There's really nothing nicer than dried figs"), that even Amitrochates, the king of the Indians, wrote to Antiochus, entreating him (it is Hegesander who tells this story) to buy and send him some sweet wine, and some dried figs, and a sophist; and that Antiochus wrote to him in answer, "The dry figs and the sweet wine we will send you; but it is not lawful for a sophist to be sold in Greece.

Indian Sources and Epigamia

Indian source Bhavishya Purana also mentioned about Chandrgupta marriage:

śakyāsihāduddhasiṁhaḥ piturarddha kṛtaṁ padam॥ candraguptastasya sutaḥ paurasādhi pateḥ sutām। sulūvasya tathodvahya yāvanī baudhatatparaḥ।। ṣaṣṭhivarṣa kṛtaṁ rājyaṁ bindusārastatobhavat। pitṛstulyaṁ kṛtaṁ rājyamaśokastanayo'bhavat ।।

(Bhavishya Purana - Pratisarga Parva 1: Chapter 6, Verse 43,44)[22]

Translation: The descendants of Shakyasingh became Lord Buddha, who ruled for half of his father's time. Chandragupta, a descendant of Buddha, married the Buddhist daughter of the Greek ruler Selucus, and he ruled for sixty years. After him, Bindusara, ruled, and eventually, Ashoka emerged as a significant ruler, continuing the lineage of Bindusara.

Chandragupta conquest of four provinces

Mainstream scholarship asserts that Chandragupta received vast territory west of the Indus, including the Hindu Kush, modern-day Afghanistan, and the Balochistan province of Pakistan.[23][24]

Seleucus Nicator ceded the Hindu Kush, Punjab and parts of Afghanistan to Chandragupta Maurya.[25] In consequence of their arrangement, Seleucus received 500 war elephants from Chandragupta Maurya, which subsequently influenced the Wars of the Diadochi in the west. Seleucus and Chandragupta also agreed to a marriage alliance, probably the marriage of Seleucus' daughter (named Berenice in Indian Pali sources) to Chandragupta.

According to Greek geographer and historian Strabo, the ceded four territories:

The geographical position of the tribes is as follows: along the Indus are the Paropamisadae, above whom lies the Paropamisus mountain: then, towards the south, the Arachoti (Arachosia): then next, towards the south, the Gedroseni (Gedrosia), with the other tribes that occupy the seaboard; and the Indus lies, latitudinally, alongside all these places; and of these places, in part, some that lie along the Indus are held by Indians, although they formerly belonged to the Persians. Alexander [III 'the Great' of Macedon] took these away from the Arians and established settlements of his own, but Seleucus Nicator gave them to Sandrocottus [Chandragupta], upon terms of intermarriage and of receiving in exchange five hundred elephants. Alongside the Paropamisadae, on the west, are situated the Arii, and alongside the Arochoti and Gedrosii the Drangae; but the Arii are situated alongside the Drangae on the north as well as on the west, almost surrounding a small part of their country. Bactriana lies to the north alongside both Aria and the Paropamisadae.

— Strabo 15.2.9[26]

He also illustrates that all these four provinces combinedly called Ariana :

Ariana is bounded on the east by the Indus River, on the south by the great sea, on the north by the Paropamisus mountain and the mountains that follow it as far as the Caspian Gates, and that its parts on the west are marked by the same boundaries by which Parthia is separated from Media and Carmania from Paraetacené and Persis.

— Strabo 15.2.8[27]

According to Pliny, the ceded four territories:

Most geographers, in fact, do not look upon India as bounded by the river Indus, but add to it the four satrapies of the Gedrose (Gedrosia), the Arachotë (Arachosia), the Aria, and the Paropamisadë, the River Cophes thus forming the extreme boundary of India.

— Pliny, Natural History VI, 23[28]

From this, it seems that Seleucus surrendered the easternmost provinces of Arachosia, Gedrosia, Paropamisadae and perhaps also Aria. On the other hand, he was accepted by other satraps of the eastern provinces. His Iranian wife may have helped him implement his rule in Bactria and Sogdiana.[30][31]

Establishment of diplomatic relations

The arrangement proved to be mutually beneficial.[4] The border between the Seleucid and Mauryan Empires remained stable in subsequent generations, and friendly diplomatic relations are reflected by the ambassador Megasthenes, and by the envoys sent westward by Chandragupta's grandson Ashoka. Chandragupta's gift of war elephants "may have alleviated the burden of fodder and the return march"[4] and allowed him to appropriately reduce the size and cost of his large army, since the major threats to his power had now all been removed.[32]

With the war elephants acquired from the Mauryas, Seleucus was able to defeat his rival, Antigonus, along with his allies at the Battle of Ipsus. Adding Antigonus's territories to his own, Seleucus would found the Seleucid Empire, which would endure as a great power in the Mediterranean and the Middle East until 64 BC.

Mauryan control of territory in Afghanistan helped guard against invasion of India from the northwest.[32] Chandragupta Maurya went on to expand his rule in India southward into the Deccan.[25]

Notes

- ↑ Hartmut Scharfe (1971) had argued that Seleucus had gained the upper hand and retained overlordship of the eastern satrapies, which were put under Chandragupta's charge in exchange for the elephants as tribute; but according to Trautmann,[2] no other scholars have agreed with this conclusion; Wheatley and Heckel state that Scharfe's argument "does not convince."[3]

References

- ↑ Grainger 2014, pp. 108–110: "Such fighting as there was produced a decisive Indian victory. [...] There is little or no evidence for the [detailed] account [...] The career of Chandragupta is as unclear as that of Seleukos in the east."

- ↑ Trautmann 2015, p. 235.

- ↑ Wheatley & Heckel 2011, p. 296.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Kosmin 2014, p. 33–34.

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, xv.2.9

- ↑ Smith, Vincent Arthur (1920), The Oxford History of India: From the Earliest Times to the End of 1911, Clarendon Press, pp. 104–106

- ↑ Bachhofer, Ludwig (1929). Early Indian Sculpture Vol. I. Paris: The Pegasus Press. pp. 239–240.

- ↑ Page 122: About the Masarh lion: "This particular example of a foreign model gets added support from the male heads of foreigners from Patna city and Sarnath since they also prove beyond doubt that a section of the elite in the Gangetic Basin was of foreign origin. However, as noted earlier, this is an example of the late Mauryan period since this is not the type adopted in any Ashoka pillar. We are, therefore, visualizing a historical situation in India in which the West Asian influence on Indian art was felt more in the late Mauryan than in the early Mauryan period. The term West Asia in this context stands for Iran and Afghanistan, where the Sakas and Pahlavas had their base-camps for eastward movement. The prelude to future inroads of the Indo-Bactrians in India had after all started in the second century B.C."... in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. pp. 88, 122. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3..

- ↑ According to Gupta this is a non-Indian face of a foreigner with a conical hat: "If there are a few faces which are nonIndian, such as one head from Sarnath with conical cap ( Bachhofer, Vol . I, Pl . 13 ), they are due to the presence of the foreigners their costumes, tastes and liking for portrait art and not their art styles." in Gupta, Swarajya Prakash (1980). The Roots of Indian Art: A Detailed Study of the Formative Period of Indian Art and Architecture, Third and Second Centuries B.C., Mauryan and Late Mauryan. B.R. Publishing Corporation. p. 318. ISBN 978-0-391-02172-3.

- ↑ Annual Report 1907-08. 1911. p. 55.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar 2003, p. 105.

- ↑ Ancient India, (Kachroo, p.196)

- ↑ The Imperial Gazetteer of India (Hunter, p.167)

- ↑ The evolution of man and society (Darlington, p.223)

- ↑ W. W. Tarn (1940). "Two Notes on Seleucid History: 1. Seleucus' 500 Elephants, 2. Tarmita", The Journal of Hellenic Studies 60, p. 84–94.

- ↑ Kosmin 2014, p. 37.

- ↑ "Pliny the Elder, The Natural History (eds. John Bostock, H. T. Riley)". Archived from the original on 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Kosmin, Paul J. (23 June 2014). The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in the Seleucid Empire. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Kosmin 2014, p. 35.

- ↑ "Problem while searching in The Literature Collection". Archived from the original on 13 March 2007.

- ↑ "The Literature Collection: The deipnosophists, or, Banquet of the learned of Athenæus (volume III): Book XIV". Archived from the original on 11 October 2007.

- ↑ Khem Raj Shri Krishna Lal, Shri Venkateshwar Steam Press. Bhavishya Maha Puran, 1959 Khem Raj Shri Krishna Lal, Shri Venkateshwar Steam Press, Mumbai.

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Walter Eugene Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology", Classical Philology 14 (4), pp. 297–313.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 [R.G. Grant: Commanders pg. 49 https://books.google.com/books?id=tFQcwH2StsMC&q=chandragupta#v=snippet&q=chandragupta&f=false]

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, xv.2.9

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, [1]

- ↑ Pliny, Natural History VI, 23

- ↑ Bernard, Paul; Pinault, Georges-Jean; Rougemont, Georges (2004). "Deux nouvelles inscriptions grecques de l'Asie centrale". Journal des Savants. 2 (1): 301 ff. doi:10.3406/jds.2004.1686.

- ↑ Vincent A. Smith (1998). Ashoka. Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-1303-1.

- ↑ Walter Eugene Clark (1919). "The Importance of Hellenism from the Point of View of Indic-Philology", Classical Philology 14 (4), p. 297-313.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Grainger 2014, pp. 108–110.

Sources

- Grainger, John D. (2014), Seleukos Nikator: Constructing a Hellenistic Kingdom, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-317-80099-6

- Kosmin, Paul J. (2014), The Land of the Elephant Kings: Space, Territory, and Ideology in Seleucid Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-72882-0

- Majumdar, Ramesh Chandra (2003) [1952], Ancient India, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 81-208-0436-8

- Trautmann, Thomas (2015), Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History, University of Chicago Press, ISBN 978-0-226-26453-0

- Wheatley, Pat; Heckel, Waldemar (2011), ""Commentary (Book 15)"", Justin: Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus: Volume II, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-927759-9